Picasso, Mallarmé, Papier Collé

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Famous Paintings of Picasso Guernica

Picasso ArtStart – 7 Dr. Hyacinth Paul https://www.hyacinthpaulart.com/ The genius of Picasso • Picasso was a cubist and known for painting, drawing, sculpture, stage design and writing. • He developed cubism along with Georges Braque • Born 25th Oct 1881 in Malaga, Spain • Spent time in Spain and France. • Died in France 8th April, 1973, Age 91 Painting education • Trained by his father at age 7 • Attended the School of Fine Arts, Barcelona • 1897, attended Madrid's Real Academia de Bellas Artes, He preferred to study the paintings of Rembrandt, El Greco, Goya and Velasquez • 1901-1904 – Blue period; 1904-1906 Pink period; 1907- 1909 – African influence 1907-1912 – Analytic Cubism; 1912-1919 - Synthetic Cubism; 1919-1929 - Neoclacissism & Surrealism • One of the greatest influencer of 20th century art. Famous paintings of Picasso Family of Saltimbanques - (1905) – National Gallery of Art , DC Famous paintings of Picasso Boy with a Pipe – (1905) – (Private collection) Famous paintings of Picasso Girl before a mirror – (1932) MOMA, NYC Famous paintings of Picasso La Vie (1903) Cleveland Museum of Art, OH Famous paintings of Picasso Le Reve – (1932) – (Private Collection Steven Cohen) Famous paintings of Picasso The Young Ladies of Avignon – (1907) MOMA, NYC Famous paintings of Picasso Ma Jolie (1911-12) Museum of Modern Art, NYC Famous paintings of Picasso The Old Guitarist (1903-04) - The Art Institute of Chicago, IL Famous paintings of Picasso Guernica - (1937) – (Reina Sofia, Madrid) Famous paintings of Picasso Three Musicians – (1921) -

Julio Gonzalez Introduction by Andrew Carnduff Ritchie, with Statements by the Artist

Julio Gonzalez Introduction by Andrew Carnduff Ritchie, with statements by the artist. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, in collaboration with the Minneapolis Institute of Art Author Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.) Date 1956 Publisher Minneapolis Institute of Art Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/3333 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art JULIO GONZALEZ JULIO GONZALEZ introduction by Andrew Carnduff Ritchie with statements by the artist The Museum of Modern Art New York in collaboration with The Minneapolis Institute of Art TRUSTEES OF THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART John Hay W hitney, Chairman of theBoard;//enry A//en Aloe, 1st Vice-Chairman; Philip L. Goodwin, 2nd Vice-Chairman; William A. M. Burden, President; Mrs. David M. Levy, 1st Vice-President; Alfred IL Barr, Jr., Mrs. Bobert Woods Bliss, Stephen C. (dark, Balph F. Colin, Mrs. W. Murray Crane,* Bene ddfarnon court, Mrs. Edsel B. Ford, A. Conger Goodyear, Mrs. Simon Guggenheim,* Wallace K. Harrison, James W. Husted,* Mrs. Albert D. Lasker, Mrs. Henry B. Luce, Ranald II. Macdonald, Mrs. Samuel A. Marx, Mrs. G. Macculloch Miller, William S. Paley, Mrs. Bliss Parkinson, Mrs. Charles S. Payson, Duncan Phillips,* Andrew CarndujJ Bitchie, David Bockefeller, Mrs. John D. Bockefeller, 3rd, Nelson A. Bockefeller, Beardsley Buml, Paul J. Sachs,* John L. Senior, Jr., James Thrall Soby, Edward M. M. Warburg, Monroe Wheeler * Honorary Trustee for Life TRUSTEES OF THE MINNEAPOLIS INSTITUTE OF ARTS Putnam D. -

PICASSO Les Livres D’Artiste E T Tis R a D’ S Vre Li S Le PICASSO

PICASSO LES LIVRES d’ARTISTE The collection of Mr. A*** collection ofThe Mr. d’artiste livres Les PICASSO PICASSO Les livres d’artiste The collection of Mr. A*** Author’s note Years ago, at the University of Washington, I had the opportunity to teach a class on the ”Late Picasso.” For a specialist in nineteenth-century art, this was a particularly exciting and daunting opportunity, and one that would prove formative to my thinking about art’s history. Picasso does not allow for temporalization the way many other artists do: his late works harken back to old masterpieces just as his early works are themselves masterpieces before their time, and the many years of his long career comprise a host of “periods” overlapping and quoting one another in a form of historico-cubist play that is particularly Picassian itself. Picasso’s ability to engage the art-historical canon in new and complex ways was in no small part influenced by his collaborative projects. It is thus with great joy that I return to the varied treasures that constitute the artist’s immense creative output, this time from the perspective of his livres d’artiste, works singularly able to point up his transcendence across time, media, and culture. It is a joy and a privilege to be able to work with such an incredible collection, and I am very grateful to Mr. A***, and to Umberto Pregliasco and Filippo Rotundo for the opportunity to contribute to this fascinating project. The writing of this catalogue is indebted to the work of Sebastian Goeppert, Herma Goeppert-Frank, and Patrick Cramer, whose Pablo Picasso. -

Guia Didáctica Gargallo

GARGALLO Guía didáctica GARGALLO Guía didáctica ¿QUIÉN ES GARGALLO? 2 Fíjate en todas estas imágenes: la mayoría de la gente nos hacemos fotos y las guar- damos como recuerdo, pero a los artistas como Pablo Gargallo les gusta también hacerse sus propios retratos. Un autorretrato no consiste en poner un ojo por aquí, o una ceja, una nariz o un labio por allí, sino en representarse como uno se siente en un momento determinado. Mirarse en un espejo y copiar con un lápiz lo que ves no es retratarse. Hay que describirse por dentro y por fuera: cómo vestimos, cómo somos, cómo nos sentimos. Si te fijas descubrirás que Gargallo se representaba con su nariz grande, su fle- quillo y sus ojos tristes. Así era como él se veía y quería que le vieran los demás.Eso sí, aunque siempre parece pensativo y serio, también podía ser muy alegre. De todas estas imágenes algunas son fotografías, otras están hechas con tinta sobre 3 papel y sólo una de ellas es una escultura, inspirada en uno de sus dibujos. ¿La ves? Debía de sentirse muy identificado para convertirlo en una obra de hierro, ¿no? Fijate en ella. ¿Por qué no buscas el dibujo que más se le parece? Después de ver cómo era, ¿te apetece viajar en el tiempo para descubrir a uno de los escultores más importantes del siglo XX? Pues allá vamos. GARGALLO Y MAELLA 4 5 Maella, víspera del día de Reyes de 1881. Son las cinco de la ma- ñana y hace mucho frío, pero en casa de la familia Gargallo todos están levantados para dar la bienvenida al pequeño Pablo, que acaba de nacer. -

Impressionist & Modern

Impressionist & Modern Art New Bond Street, London I 10 October 2019 Lot 8 Lot 2 Lot 26 (detail) Impressionist & Modern Art New Bond Street, London I Thursday 10 October 2019, 5pm BONHAMS ENQUIRIES PHYSICAL CONDITION IMPORTANT INFORMATION 101 New Bond Street London OF LOTS IN THIS AUCTION The United States Government London W1S 1SR India Phillips PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE IS NO has banned the import of ivory bonhams.com Global Head of Department REFERENCE IN THIS CATALOGUE into the USA. Lots containing +44 (0) 20 7468 8328 TO THE PHYSICAL CONDITION OF ivory are indicated by the VIEWING [email protected] ANY LOT. INTENDING BIDDERS symbol Ф printed beside the Friday 4 October 10am – 5pm MUST SATISFY THEMSELVES AS lot number in this catalogue. Saturday 5 October 11am - 4pm Hannah Foster TO THE CONDITION OF ANY LOT Sunday 6 October 11am - 4pm Head of Department AS SPECIFIED IN CLAUSE 14 PRESS ENQUIRIES Monday 7 October 10am - 5pm +44 (0) 20 7468 5814 OF THE NOTICE TO BIDDERS [email protected] Tuesday 8 October 10am - 5pm [email protected] CONTAINED AT THE END OF THIS Wednesday 9 October 10am - 5pm CATALOGUE. CUSTOMER SERVICES Thursday 10 October 10am - 3pm Ruth Woodbridge Monday to Friday Specialist As a courtesy to intending bidders, 8.30am to 6pm SALE NUMBER +44 (0) 20 7468 5816 Bonhams will provide a written +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 25445 [email protected] Indication of the physical condition of +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 Fax lots in this sale if a request is received CATALOGUE Julia Ryff up to 24 hours before the auction Please see back of catalogue £22.00 Specialist starts. -

Press Information

PRESS INFORMATION PICASSO IN ISTANBUL SAKIP SABANCI MUSEUM, ISTANBUL 24 November 2005 to 26 March 2006 Press enquiries: Erica Bolton and Jane Quinn 10 Pottery Lane London W11 4LZ Tel: 020 7221 5000 Fax: 020 7221 8100 [email protected] Contents Press Release Chronology Complete list of works Biographies 1 Press Release Issue: 22 November 2005 FIRST PICASSO EXHIBITION IN TURKEY IS SELECTED BY THE ARTIST’S GRANDSON Picasso in Istanbul, the first major exhibition of works by Pablo Picasso to be staged in Turkey, as well as the first Turkish show to be devoted to a single western artist, will go on show at the Sakip Sabanci Museum in Istanbul from 24 November 2005 to 26 March 2006. Picasso in Istanbul has been selected by the artist‟s grandson Bernard Ruiz-Picasso and Marta-Volga Guezala. Picasso expert Marilyn McCully and author Michael Raeburn are joint curators of the exhibition and the catalogue, working together with Nazan Olçer, Director of the Sakip Sabanci Museum, and Selmin Kangal, the museum‟s Exhibitions Manager. The exhibition will include 135 works spanning the whole of the artist‟s career, including paintings, sculptures, ceramics, textiles and photographs. The works have been loaned from private collections and major museums, including the Picasso museums in Barcelona and Paris. The exhibition also includes significant loans from the Fundaciñn Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso para el Arte. A number of rarely seen works from private collections will be a special highlight of the exhibition, including tapestries of “Les Demoiselles d‟Avignon” and “Les femmes à leur toilette” and the unique bronze cast, “Head of a Warrior, 1933”. -

* Kiki from Montparnasse for More Than Twenty Years, She Was the Muse of the Parisian Neighbourhood of Montparnasse. Alice Prin

Blog Our blog will be a place used to tell you in detail all those museum's daily aspects, its internal functioning, its secrets, anecdotes and curiosities widely unknown about the building and our collections. How does people work in the museum when it is closed? What secrets lay behind the exemplars of our library? What do the “inhabitants” of our collections hide?... On this space the MACA completely opens its doors to everyone who wants to know us deeper. Welcome to the MACA! • Kiki de Montparnasse (Kiki from Montparnasse) | MACA's celebrities • Miró y el objeto (Miró and the object) | Publications • Derivas de la geometría (Geometry drifts) | Publications • Los patios de canicas (Marbles patios) | MACA's secrets • La Montserrat | MACA's celebrities • Una pasión privada (A private passion) | Publications • Estudiante en prácticas (Apprentice) | MACA's secrets • Arquitectura y arte (Architecture and art) | Publications • Nuestro público (Our public) | MACA's secrets • Gustavo Torner | MACA's celebrities • René Magritte y la Publicidad (René Magritte and Advertising) |MACA's celebrities * Kiki from Montparnasse For more than twenty years, she was the muse of the Parisian neighbourhood of Montparnasse. Alice Prin, who was commonly and widely called Kiki, posed for the best painters of the inter-war Europe and socialized with the most relevant artists of that period. Alice Ernestine Prin, Kiki, was born on the 2nd of October 1901 within a humble family from Châtillon-sur-Seine, a small city of Borgoña. Kiki visited Paris for the first time when she was thirteen and when she was fourteen her family send her to work in the capital. -

Picasso Et La Famille 27-09-2019 > 06-01-2020

Picasso et la famille 27-09-2019 > 06-01-2020 1 Cette exposition est organisée par le Musée Sursock avec le soutien exceptionnel du Musée national Picasso-Paris dans le cadre de « Picasso-Méditerranée », et avec la collaboration du Ministère libanais de la Culture. Avec la généreuse contribution de Danièle Edgar de Picciotto et le soutien de Cyril Karaoglan. Commissaires de l’exposition : Camille Frasca et Yasmine Chemali Scénographie : Jacques Aboukhaled Graphisme de l’exposition : Mind the gap Éclairage : Joe Nacouzi Graphisme de la publication et photogravure : Mind the gap Impression : Byblos Printing Avec la contribution de : Tinol Picasso-Méditerranée, une initiative du Musée national Picasso-Paris « Picasso-Méditerranée » est une manifestation culturelle internationale qui se tient de 2017 à 2019. Plus de soixante-dix institutions ont imaginé ensemble une programmation autour de l’oeuvre « obstinément méditerranéenne » de Pablo Picasso. À l’initiative du Musée national Picasso-Paris, ce parcours dans la création de l’artiste et dans les lieux qui l’ont inspiré offre une expérience culturelle inédite, souhaitant resserrer les liens entre toutes les rives. Maternité, Mougins, 30 août 1971 Huile sur toile, 162 × 130 cm Musée national Picasso-Paris. Dation Pablo Picasso, 1979. MP226 © RMN-Grand Palais / Adrien Didierjean © Succession Picasso 2019 L’exposition Picasso et la famille explore les rapports de Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) à la notion de noyau familial, depuis la maternité jusqu’aux jeux enfantins, depuis l’image d’une intimité conceptuelle à l’expérience multiple d’une paternité sous les feux des projecteurs. Réunissant dessins, gravures, peintures et sculptures, l’exposition survole soixante-dix-sept ans de création, entre 1895 et 1972, au travers d’une sélection d’œuvres marquant des points d’orgue dans la longue vie familiale et sentimentale de l’artiste et dont la variété des formes illustre la réinvention constante du vocabulaire artistique de Picasso. -

Pablo Picasso, Published by Christian Zervos, Which Places the Painter of the Demoiselles Davignon in the Context of His Own Work

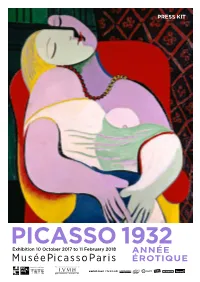

PRESS KIT PICASSO 1932 Exhibition 10 October 2017 to 11 February 2018 ANNÉE ÉROTIQUE En partenariat avec Exposition réalisée grâce au soutien de 2 PICASSO 1932 ANNÉE ÉROTIQUE From 10 October to the 11 February 2018 at Musée national Picasso-Paris The first exhibition dedicated to the work of an artist from January 1 to December 31, the exhibition Picasso 1932 will present essential masterpieces in Picassos career as Le Rêve (oil on canvas, private collection) and numerous archival documents that place the creations of this year in their context. This event, organized in partnership with the Tate Modern in London, invites the visitor to follow the production of a particularly rich year in a rigorously chronological journey. It will question the famous formula of the artist, according to which the work that is done is a way of keeping his journal? which implies the idea of a coincidence between life and creation. Among the milestones of this exceptional year are the series of bathers and the colorful portraits and compositions around the figure of Marie-Thérèse Walter, posing the question of his works relationship to surrealism. In parallel with these sensual and erotic works, the artist returns to the theme of the Crucifixion while Brassaï realizes in December a photographic reportage in his workshop of Boisgeloup. 1932 also saw the museification of Picassos work through the organization of retrospectives at the Galerie Georges Petit in Paris and at the Kunsthaus in Zurich, which exhibited the Spanish painter to the public and critics for the first time since 1911. The year also marked the publication of the first volume of the Catalog raisonné of the work of Pablo Picasso, published by Christian Zervos, which places the painter of the Demoiselles dAvignon in the context of his own work. -

A Finding Aid to the José De Creeft Papers,1871-2004, Bulk 1910S-1980S, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the José de Creeft Papers,1871-2004, bulk 1910s-1980s, in the Archives of American Art Jayna M. Josefson Funding for the processing of this collection was provided by the Smithsonian Institution Collections Care and Preservation Fund 13 May 2016 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 4 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Biographical Material, 1914-1979............................................................. 6 Series 2: Correspondence, 1910s-1980s................................................................. 7 Series 3: Diaries, -

Pablo Picasso En Quelques Dates

DOSSIER E PEDAGOGIQU Chers enseignants, Pablo Picasso en quelques dates Dans ce dossier pédagogique nous vous proposons une démarche pour « apprendre 1881 : Naissance de Pablo Picasso à Malaga (Andalousie) le 25 octobre. à regarder » : une éducation au regard, départ d’une réflexion et d’une approche vers 1891 : Installation à La Corogne où son père, José Luis Blasco, est nommé professeur l’ouverture et la découverte de l’univers de Picasso durant son séjour perpignanais. de dessin au lycée de la ville. Pablo suit des cours de dessin. 1895 : Déménagement de la famille à Barcelone. Picasso réussit le concours d’entrée à Vous y trouverez des propositions afin de travailler en amont, pendant et après la visite, l’école des Beaux-Arts, 4 ans avant l’âge d’entrée officiel. En 1896, il remporte une médaille d’or de peinture. afin que vos élèves puissent construire leur parcours artistique et culturel. 1900 : Premier voyage à Paris. Nous avons souhaité également croiser les regards afin de décloisonner les matières et 1901-1904 : Installation à Paris au Bateau-Lavoir ; rencontre avec des poètes et artistes. Suicide de son ami Casagemas qui le plonge dans une mélancolie permettre ainsi à l’élève d’accéder au travail de l’artiste par différentes entrées. qui inonde ses toiles : c’est la période bleue. Bonne lecture, 1905 : Retour de la joie. Fernande Olivier est sa nouvelle compagne : c’est la période rose, la musique, le cirque et la lumière font leur apparition. l’équipe du Service des publics du musée. 1907 : Invention du cubisme. Aux côtés de Georges Braque, Picasso invente une manière de peindre totalement inédite qui transforme la réalité en mille facettes, en petits cubes, s’inspirant parfois des cultures primitives (Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907, PROPOSITIONS PÉDAGOGIQUES p. -

Picasso's Composition

PABLO PICASSO – AGES 5 – 7 | ONLINE EDITION Step 1 - Introducing the Master Artist: Slideshow Guide MOTIVATION BEGIN READING HERE Today let’s pretend that you have a father who is a famous artist. He wants to paint your PORTRAIT, so you pose for him in his STUDIO. What is a studio? (PLACE WHERE AN ARTIST PAINTS) He is going to paint you twice. In the first portrait you. will be sitting in a chair wearing a clown costume. Can you make that pose? (SHOW POSE) Good! The second one also has you sitting in a chair, but this time you will be holding an orange, which is your favorite fruit. Can you make that pose? (SHOW POSE) Excellent pose! You are a good artist’s model! Do you think the portraits will look the same, because the same artist paints them? Let’s see how this famous artist painted his children. Click Start Lesson To Begin 1. & 2. PAUL AS HARLEQUIN and PALOMA WITH ORANGE Show slide 1 for 3-4 seconds, then show slide 2 Does it look like the same artist painted both portraits? (NO) Do they look very different from each other? (YES) But the same artist painted them! Which one of these portraits do you like the best? (SHOW BOTH IMAGES AGAIN) Do you think his children liked their portraits? These portraits don’t look like the same person made them because they were not painted at the same time. Our artist kept changing the way he painted and became very famous as a result. Let’s meet today’s master artist.