Chapter 2. Ocean Observations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PICES Sci. Rep. No. 2, 1995

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page FOREWORD vii Part 1. GENERAL INTRODUCTION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 1.0 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION IN THE OKHOTSK SEA AND KURIL REGION 3 1.1 Okhotsk Sea water mass modification 3 1.1.1Dense shelf water formation in the northwestern Okhotsk Sea 3 1.1.2Soya Current study 4 1.1.3East Sakhalin Current and anticyclonic Kuril Basin flow 4 1.1.4West Kamchatka Current 5 1.1.5Tides and sea level in the Okhotsk Sea 5 1.2 Influence of Okhotsk Sea waters on the subarctic Pacific and Oyashio 6 1.2.1Kuril Island strait transports (Bussol', Kruzenshtern and shallower straits) 6 1.2.2Kuril region currents: the East Kamchatka Current, the Oyashio and large eddies 7 1.2.3NPIW transport and formation rate in the Mixed Water Region 7 1.3 Sea ice analysis and forecasting 8 2.0 PHYSICAL OCEANOGRAPHIC OBSERVATIONS 9 2.1 Hydrographic observations (bottle and CTD) 9 2.2 Direct current observations in the Okhotsk and Kuril region 11 2.3 Sea level measurements 12 2.4 Sea ice observations 12 2.5 Satellite observations 12 Part 2. REVIEW OF OCEANOGRAPHY OF THE OKHOTSK SEA AND OYASHIO REGION 15 1.0 GEOGRAPHY AND PECULIARITIES OF THE OKHOTSK SEA 16 2.0 SEA ICE IN THE OKHOTSK SEA 17 2.1 Sea ice observations in the Okhotsk Sea 17 2.2 Ease of ice formation in the Okhotsk Sea 17 2.3 Seasonal and interannual variations of sea ice extent 19 2.3.1Gross features of the seasonal variation in the Okhotsk Sea 19 2.3.2Sea ice thickness 19 2.3.3Polynyas and open water 19 2.3.4Interannual variability 20 2.4 Sea ice off the coast of Hokkaido 21 -

Fronts in the World Ocean's Large Marine Ecosystems. ICES CM 2007

- 1 - This paper can be freely cited without prior reference to the authors International Council ICES CM 2007/D:21 for the Exploration Theme Session D: Comparative Marine Ecosystem of the Sea (ICES) Structure and Function: Descriptors and Characteristics Fronts in the World Ocean’s Large Marine Ecosystems Igor M. Belkin and Peter C. Cornillon Abstract. Oceanic fronts shape marine ecosystems; therefore front mapping and characterization is one of the most important aspects of physical oceanography. Here we report on the first effort to map and describe all major fronts in the World Ocean’s Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs). Apart from a geographical review, these fronts are classified according to their origin and physical mechanisms that maintain them. This first-ever zero-order pattern of the LME fronts is based on a unique global frontal data base assembled at the University of Rhode Island. Thermal fronts were automatically derived from 12 years (1985-1996) of twice-daily satellite 9-km resolution global AVHRR SST fields with the Cayula-Cornillon front detection algorithm. These frontal maps serve as guidance in using hydrographic data to explore subsurface thermohaline fronts, whose surface thermal signatures have been mapped from space. Our most recent study of chlorophyll fronts in the Northwest Atlantic from high-resolution 1-km data (Belkin and O’Reilly, 2007) revealed a close spatial association between chlorophyll fronts and SST fronts, suggesting causative links between these two types of fronts. Keywords: Fronts; Large Marine Ecosystems; World Ocean; sea surface temperature. Igor M. Belkin: Graduate School of Oceanography, University of Rhode Island, 215 South Ferry Road, Narragansett, Rhode Island 02882, USA [tel.: +1 401 874 6533, fax: +1 874 6728, email: [email protected]]. -

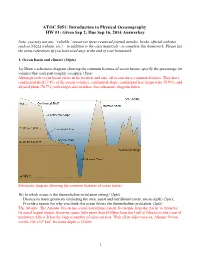

ATOC 5051: Introduction to Physical Oceanography HW #1: Given Sep 2; Due Sep 16, 2014 Answerkey

ATOC 5051: Introduction to Physical Oceanography HW #1: Given Sep 2; Due Sep 16, 2014 Answerkey Note: you may use any “reliable” resources (peer-reviewed journal articles, books, official websites such as NOAA website, etc.) – in addition to the class materials - to complete this homework. Please list the extra-references (if you have used any) at the end of your homework. 1. Ocean basin and climate (30pts) 1a) Draw a schematic diagram showing the common features of ocean basins; specify the percentage (in volume) that each part roughly occupies. (5pts) Although each ocean basin varies in its location and size, all oceans have common features. They have continental shelf (7.4% of the ocean volume), continental slope, continental rise (slope+rise 15.9%), and abyssal plain (76.7%) with ridges and trenches. See schematic diagram below. Schematic diagram showing the common features of ocean basins. 1b) In which ocean is the thermohaline circulation strong? (2pts) Discuss its basin geometry (including the area, zonal and meridional extent, mean depth) (3pts); Provide a reason for why you think this ocean favors the thermohaline circulation. (2pts) The Atlantic. The Atlantic Ocean has a total meridional extent: It extends from the Arctic to Antarctic. Its zonal largest extent, however, spans little more than 8300km from the Gulf of Mexico to the coast of northwest Africa. It has the largest number of adjacent seas. With all its adjacent seas, Atlantic Ocean covers 106 ×106 km2. Its mean depth is 3300m. 1 The full North-South extent of the Atlantic allows the ocean to extend farther north, where it is cold enough to produce heavier surface water than the subsurface water and thus cause convection and deep- water formation. -

Global Ocean Surface Velocities from Drifters: Mean, Variance, El Nino–Southern~ Oscillation Response, and Seasonal Cycle Rick Lumpkin1 and Gregory C

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH: OCEANS, VOL. 118, 2992–3006, doi:10.1002/jgrc.20210, 2013 Global ocean surface velocities from drifters: Mean, variance, El Nino–Southern~ Oscillation response, and seasonal cycle Rick Lumpkin1 and Gregory C. Johnson2 Received 24 September 2012; revised 18 April 2013; accepted 19 April 2013; published 14 June 2013. [1] Global near-surface currents are calculated from satellite-tracked drogued drifter velocities on a 0.5 Â 0.5 latitude-longitude grid using a new methodology. Data used at each grid point lie within a centered bin of set area with a shape defined by the variance ellipse of current fluctuations within that bin. The time-mean current, its annual harmonic, semiannual harmonic, correlation with the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI), spatial gradients, and residuals are estimated along with formal error bars for each component. The time-mean field resolves the major surface current systems of the world. The magnitude of the variance reveals enhanced eddy kinetic energy in the western boundary current systems, in equatorial regions, and along the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, as well as three large ‘‘eddy deserts,’’ two in the Pacific and one in the Atlantic. The SOI component is largest in the western and central tropical Pacific, but can also be seen in the Indian Ocean. Seasonal variations reveal details such as the gyre-scale shifts in the convergence centers of the subtropical gyres, and the seasonal evolution of tropical currents and eddies in the western tropical Pacific Ocean. The results of this study are available as a monthly climatology. Citation: Lumpkin, R., and G. -

Response of Biological Productivity to North Atlantic Marine Front Migration During the Holocene

Clim. Past, 17, 379–396, 2021 https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-17-379-2021 © Author(s) 2021. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Response of biological productivity to North Atlantic marine front migration during the Holocene David J. Harning1,2,3, Anne E. Jennings2,3, Denizcan Köseoglu˘ 4, Simon T. Belt4, Áslaug Geirsdóttir1, and Julio Sepúlveda2,3 1Faculty of Earth Sciences, University of Iceland, Reykjavík, Iceland 2Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research, University of Colorado, Boulder, USA 3Department of Geological Sciences, University of Colorado, Boulder, USA 4Biogeochemistry Research Centre, Plymouth University, Plymouth, UK Correspondence: David J. Harning ([email protected]) Received: 9 September 2020 – Discussion started: 18 September 2020 Revised: 22 December 2020 – Accepted: 4 January 2021 – Published: 8 February 2021 Abstract. Marine fronts delineate the boundary between dis- 1 Introduction tinct water masses and, through the advection of nutrients, are important facilitators of regional productivity and bio- diversity. As the modern climate continues to change, the Marine fronts are the boundary that separates different water migration of frontal zones is evident, but a lack of infor- masses and are a globally ubiquitous feature in the oceans mation about their status prior to instrumental records hin- (Belkin et al., 2009). By nature, marine fronts are charac- ders future projections. Here, we combine data from lipid terized by strong horizontal gradients of typically correlated -

Exceptional Ocean Surface Conditions on the SE Greenland Shelf During

PUBLICATIONS Paleoceanography RESEARCH ARTICLE Exceptional ocean surface conditions on the SE 10.1002/2015PA002849 Greenland shelf during the Medieval Key Points: Climate Anomaly • Ocean surface conditions were reconstructed from the SE Greenland Arto Miettinen1, Dmitry V. Divine1,2, Katrine Husum1, Nalan Koç1, and Anne Jennings3 shelf for the last millennium • The Medieval Climate Anomaly 1000 1Norwegian Polar Institute, Tromsø, Norway, 2Department of Mathematics and Statistics, Arctic University of Norway, to 1200 C.E. represents the warmest 3 period of the late Holocene Tromsø, Norway, INSTAAR and Department of Geological Sciences, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, Colorado, USA • Solar forcing amplified by atmospheric forcing was behind the surface conditions Abstract Diatom inferred 2900 year long records of August sea surface temperature (aSST) and April sea ice concentration (aSIC) are generated from a marine sediment core from the SE Greenland shelf with – Supporting Information: a special focus on the interval ca. 870 1910 Common Era (C.E.) reconstructed in subdecadal temporal • Figures S1–S5 resolution. The Medieval Climate Anomaly (MCA) between 1000 and 1200 C.E. represents the warmest ocean surface conditions of the SE Greenland shelf over the late Holocene (880 B.C.E. (before the Common Era) to Correspondence to: 1910 C.E.). It was characterized by abrupt, decadal to multidecadal changes, such as an abrupt warming of A. Miettinen, [email protected] ~2.4°C in 55 years around 1000 C.E. Temperature changes of these magnitudes are rare on the North Atlantic proxy data. Compared to regional air temperature reconstructions, our results indicate a lag of about 50 years in ocean surface warming either due to increased freshwater discharge from the Greenland ice sheet or Citation: Miettinen, A., D. -

Book 31 Oyashio Current.Indb

(MPCBM*OUFSOBUJPOBM 8BUFST"TTFTTNFOU 0ZBTIJP$VSSFOU (*8"3FHJPOBMBTTFTTNFOU "MFLTFFW "7 ,ISBQDIFOLPW '' #BLMBOPW 1+ #MJOPW :( ,BDIVS "/ .FEWFEFWB *" .JOBLJS 1"BOE(%5JUPWB Global International Waters Assessment Regional assessments Other reports in this series: Russian Arctic – GIWA Regional assessment 1a Caribbean Sea/Small Islands – GIWA Regional assessment 3a Caribbean Islands – GIWA Regional assessment 4 Barents Sea – GIWA Regional assessment 11 Baltic Sea – GIWA Regional assessment 17 Caspian Sea – GIWA Regional assessment 23 Aral Sea – GIWA Regional assessment 24 Gulf of California/Colorado River Basin – GIWA Regional assessment 27 Yellow Sea – GIWA Regional assessment 34 East China Sea – GIWA Regional assessment 36 Patagonian Shelf – GIWA Regional assessment 38 Brazil Current – GIWA Regional assessment 39 Amazon Basin – GIWA Regional assessment 40b Canary Current – GIWA Regional assessment 41 Guinea Current – GIWA Regional assessment 42 Lake Chad Basin – GIWA Regional assessment 43 Benguela Current – GIWA Regional assessment 44 Indian Ocean Islands – GIWA Regional assessment 45b East African Rift Valley Lakes – GIWA Regional assessment 47 South China Sea – GIWA Regional assessment 54 Mekong River – GIWA Regional assessment 55 Sulu-Celebes (Sulawesi) Sea – GIWA Regional assessment 56 Indonesian Seas – GIWA Regional assessment 57 Pacifi c Islands – GIWA Regional assessment 62 Humboldt Current – GIWA Regional assessment 64 Global International Waters Assessment Regional assessment 31 Oyashio Current GIWA report production Series editor: -

Response of Biological Productivity to North Atlantic Marine Front Migration During the Holocene David J

Response of biological productivity to North Atlantic marine front migration during the Holocene David J. Harning1,2, Anne E. Jennings2, Denizcan Köseoğlu3, Simon T. Belt3, Áslaug Geirsdóttir1, Julio Sepúlveda2 5 1Faculty of Earth Sciences, University of Iceland, Reykjavík, Iceland 2Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research, University of Colorado and Department of Geological Sciences, University of Colorado, Boulder, USA 3Biogeochemistry Research Centre, Plymouth University, Plymouth, UK Correspondence to: David J. Harning ([email protected]) 10 Abstract. Marine fronts delineate the boundary between distinct water masses and, through the advection of nutrients, are important facilitators of regional productivity and biodiversity. As the modern climate continues to change the migration of frontal zones is evident, but a lack of information about their status prior to instrumental records hinders future projections. Here, we combine data from lipid biomarkers (archaeal isoprenoid glycerol dibiphytanyl glycerol tetraethers and algal highly branched isoprenoids) with planktic and benthic foraminifera assemblage to detail the biological response of the marine Arctic 15 and Polar Front migrations on the North Iceland Shelf (NIS) over the last 8 ka. This multi-proxy approach enables us to quantify the thermal structure relating to Arctic and Polar Front migration, and test how this influences the corresponding changes in local pelagic productivity. Our data show that following an interval of Atlantic Water influence, the Arctic Front and its associated high pelagic productivity migrated south-eastward to the NIS by ~6.1 ka BP. Following a subsequent trend Deleted: stabilized of regional cooling, Polar Water from the East Greenland Current and the associated Polar Front spread onto the NIS by ~3.8 Deleted: on 20 ka BP, greatly diminishing local algal productivity through the Little Ice Age. -

Pacific Oceanography

Scientific Journal PACIFIC OCEANOGRAPHY Volume 2, Number 1-2 2004 FAR EASTERN REGIONAL HYDROMETEOROLOGICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE Russian Federal Service For Hydrometeorology and Environmental Monitoring (ROSHYDROMET) http://po.hydromet.com Editor-in-Chief Dr. Yuriy N. Volkov FERHRI, Vladivostok, Russia / Email: [email protected] Editor Dr. Igor E. Kochergin FERHRI, Vladivostok, Russia / Email: [email protected] Editor Dr. Mikhail A. Danchenkov FERHRI, Vladivostok, Russia / Email: [email protected] Executive Secretary Ms. Elena S. Borozdinova FERHRI, Vladivostok, Russia / Email: [email protected] Editorial Board D.G. Aubrey (Woods Hole Group, Falmouth, USA) J.E. O’Reilly (Exxon/Mobil, Houston, USA) T.A. Belan (FERHRI, Vladivostok, Russia) Y.D. Resnyansky (Hydrometcenter of RF, Moscow, Russia) I.M. Belkin (GSO, University of Rhode Island, Narragansett, USA) S.C. Riser (University of Washington, Seattle, USA) G.H. Hong (KORDI, Ansan, Republic of Korea) G.V. Shevchenko (SakhNIRO, Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk, Russia) E.V. Karasev (FERHRI, Vladivostok, Russia) M. Takematsu (RIAM, Kyushu University (retired), Fukuoka, Japan) K. Kim (Seoul National University, Seoul, Republic of Korea) A.V. Tkalin (FERHRI, Vladivostok, Russia) V.B. Lobanov (POI FEBRAS, Vladivostok, Russia) S.M. Varlamov (RIAM, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan) Yu.A. Mikishin (FESU, Vladivostok, Russia) J.H. Yoon (RIAM, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan) A.B. Rabinovich (Institute of Oceanology RAS, Moscow, Russia) Secretariat contact: Elena Borozdinova, Pacific Oceanography, -

Aquatic Sciences and Fisheries Information System: Geographic

ASFIS-7 (Rev. 3) AQUATIC SCIENCES AND FISHERIES INFORMATION SYSTEM GEOGRAPHIC AUTHORITY LIST ASFIS REFERENCE SERIES, No. 7 Revision 3 ASFIS-7 (Rev. 3) AQUATIC SCIENCES AND FISHERIES INFORMATION SYSTEM GEOGRAPHIC AUTHORITY LIST edited by David S Moulder Plymouth Marine Laboratory Plymouth, United Kingdom revised by Ian Pettman and Hardy Schwamm Freshwater Biological Association Ambleside, Cumbria, United Kingdom Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, 2019 Required citation: FAO. 2019. Aquatic sciences and fisheries information system. Geographic authority list. ASFIS-7 (Rev. 3) Rome. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. ISBN 978-92-5-131173-8 © FAO, 2019 Some rights reserved. This work is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo/legalcode/legalcode). -

The Large Scale Ocean Circulation and Physical Processes Controlling Pacific-Arctic Interactions

Chapter 5 The Large Scale Ocean Circulation and Physical Processes Controlling Pacifi c-Arctic Interactions Wieslaw Maslowski , Jaclyn Clement Kinney , Stephen R. Okkonen, Robert Osinski , Andrew F. Roberts , and William J. Williams Abstract Understanding oceanic effects on climate in the Pacifi c-Arctic region requires knowledge of the mean circulation and its variability in the region. This chapter presents an overview of the mean regional circulation patterns, spatial and temporal variability, critical processes and property fl uxes from the northern North Pacifi c into the western Arctic Ocean, with emphasis on their impact on sea ice. First, results from a high-resolution, pan-Arctic ice-ocean model forced with realistic atmospheric data and observations in the Alaskan Stream, as well as exchanges across the Aleutian Island Passes, are discussed. Next, general ocean circulation in the deep Bering Sea, shelf-basin exchange, and fl ow across the Bering shelf are investigated. Also, fl ow across the Chukchi Sea, pathways of Pacifi c summer water and oceanic forcing of sea ice in the Pacifi c-Arctic region are analyzed. Finally, we hypothesize that the northward advection of Pacifi c Water together with the excess oceanic heat that has accumulated below the surface mixed layer in the western Arctic Ocean due to diminishing sea ice cover and subsequent increased solar insolation are critical factors affecting sea ice growth in winter and melt the following year. W. Maslowski (*) • J. Clement Kinney Department of Oceanography , Graduate School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, Naval Postgraduate School , Dyer Road, Bldg. SP339B , Monterey , CA 93943 , USA e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] S. -

KUROSHIO and OYASHIO CURRENTS 1413 to Provide Better Overwinter Conditions for the Krill

KUROSHIO AND OYASHIO CURRENTS 1413 to provide better overwinter conditions for the krill. Further Reading Salps compete with krill for phytoplankton } in poor sea ice years salp numbers are increased and Constable AJ, de la Mare W, Agnew DJ, Everson I and Miller D (2000) Managing Rsheries to krill recruitment is reduced. Further north in their conserve the Antarctic marine ecosystem: practical range, E. superba abundance is dependent on the implementation of the Convention on the Conserva- transport of krill in the ocean currents as well as tion of the Antarctic Marine Living Resources Suctuations in the strength of particular cohorts. (CCAMLR). ICES Journal of Marine Science 57: Given the importance of euphausiids in marine 778}791. food webs throughout the world’s oceans, they are Everson I (ed.) (2000) Krill: Biology, Ecology and Fishe- potentially important indicator species for detecting ries. Oxford: Blackwell Science. and understanding climate change effects. Changes Everson I (2000) Introducing krill. In: Everson I (ed.) in ocean circulation or environmental regimes will Krill: Biology, Ecology and Fisheries. Oxford: Black- be reSected in changes in growth, development, well Science. recruitment success, and distribution. These effects Falk-Petersen S, Hagen W, Kattner G, Clarke A and Sargent J (2000) Lipids, trophic relationship, may be most notable at the extremes of their distri- and biodiversity in Arctic and Antarctic krill. bution where any change in the pattern of variation Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences will result in major changes in food web structure. 57: 178}191. Given their signiRcance as prey to many commer- Mauchline JR (1980) The biology of the Euphausids.