Download (6MB)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State of Operations Update

March 19, 2018 State of Operations Update Dear Valued Customer, We'd like to provide you with the latest Safmarine North America operational details. Vessel Operations Please see below for confirmed operational statuses of impacted vessels. Please be advised that vessel delays may be a result of a combination of standard seasonal contingencies and are not solely a result of weather impact – these details are subject to change. Service Vessel Updates Maersk South Africa (Pty) Ltd, Registration No. 1992/005770/07 acting as agent on behalf of Maersk Line A/S, (incorporated in Denmark)SA Reg. No. 2015/028124/10 trading as Safmarine, Address of registered office: Safmarine Quay – The Clocktower Precinct, V&A Waterfront, Cape Town, 8001 – PO Box 27, Cape Town, 8000; Telephone: +27(0)21 408 6911 Facsimile: +27(0)21 408 6345 Email: [email protected]; Web www.safmarine.com Terminal Operations Port Updates Inland Operations We would like to keep you updated with an overview of inland operations to give you visibility into the delivery and rail capabilities in key regions. Please reference the below for your convenience: GREEN • Imports: Most if not all containers are delivered on or before last free day. • Exports: Will make intended port/rail cut if booked 72 hours in advance. Shortage of hazardous drivers may still occur. Maersk South Africa (Pty) Ltd, Registration No. 1992/005770/07 acting as agent on behalf of Maersk Line A/S, (incorporated in Denmark)SA Reg. No. 2015/028124/10 trading as Safmarine, Address of registered office: Safmarine Quay – The Clocktower Precinct, V&A Waterfront, Cape Town, 8001 – PO Box 27, Cape Town, 8000; Telephone: +27(0)21 408 6911 Facsimile: +27(0)21 408 6345 Email: [email protected]; Web www.safmarine.com YELLOW • Imports: Delivering on or before last free day depends on commodity type and mileage. -

Safmarine Customer Advisory

April 27, 2018 Advance Containerized Cargo Loading Notices (Pre-Arrival Manifest) – South Africa Dear Valued Customers, The Customs Authority in South Africa has recently announced the full implementation of the Customs Control Act, 2014. The first phase of the Reporting of Conveyances and Goods (“RCG”) under the current Customs and Excise Act, 1964 has been implemented 20th April 2018. The RCG project is intended to provide customs control of all vessels, trains, vehicles, goods and persons entering or leaving South Africa. In order to comply with all customs obligations, advanced containerized cargo loading notices must be transmitted to customs at least 24 hours before the first container is loaded on board the vessel that will transport the cargo to South Africa. This applies to both cargo destined for and to be transshipped via South African ports. At this time, we would like to advise that customers shipping cargo to South Africa should make arrangements to be in compliance with this regulation. We will update you further as information becomes available on mandatory enforcement. Frequently asked questions as per the SARS website: What does RCG stand for and where does it fit in? RCG is an acronym for Reporting of Conveyances and Goods and it is one of the three major projects (the other two being Registration, Licensing and Accreditation (RLA) and Declaration Processing (DPS)) being undertaken under the New Customs Act Programme (NCAP) which is charged with operationalizing the Customs Control Act, 2014 and the Customs Duty Act, 2014. Under what legislation will the first phase of the RCG implementation take place? The rules to section 8 of the Customs and Excise Act No.91 of 1964 will be amended to form the legislative basis for the implementation of RCG. -

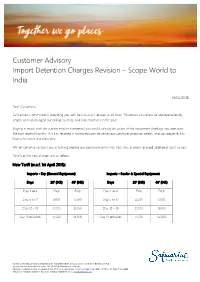

Customer Advisory Import Detention Charges Revision – Scope World to India

Customer Advisory Import Detention Charges Revision – Scope World to India 01/03/2018 Dear Customers, Safmarine is committed in providing you with best-in-class services at all times. To remain cost effective and operationally simple we had changed our billing currency and slab structures in the past. Staying in touch with the current market economics you would already be aware of the equipment shortage situation over the past several months. This has resulted in increased costs to serve your container provision needs, and consequently has lead us to revise our slab rates. We will continue to assist you in turning around our containers within the free time, in order to avoid additional costs to you. Details of the new charges are as follows: New Tariff (w.e.f. 1st April 2018): Imports - Dry (General Equipment) Imports - Reefer & Special Equipment Days 20' (INR) 40' (INR) Days 20' (INR) 40' (INR) Day 1 to 4 Free Free Day 1 to 4 Free Free Day 5 to 11 3000 6,000 Day 5 to 11 4,500 9,000 Day 12 - 18 4,500 9,000 Day 12 - 18 5,500 11,000 Day 19 onwards 6,500 13,000 Day 19 onwards 7,500 15,000 Maersk South Africa (Pty) Ltd, Registration No. 1992/005770/07 acting as agent on behalf of Maersk Line A/S, (incorporated in Denmark)SA Reg. No. 2015/028124/10 trading as Safmarine, Address of registered office: Roggebaai Place, 8th Floor, 4 Jetty Street, Foreshore, Cape Town, 8001 – PO Box 27, Cape Town, 8000; Telephone: +27(0)21 408 6911 Facsimile: +27(0)21 408 6345 Email: [email protected]; Old Tariff (Valid till 31st March 2018): Imports - Dry (General Equipment) Imports - Reefer & Special Equipment Days 20' (INR) 40' (INR) Days 20' (INR) 40' (INR) Day 1 to 5 Free Free Day 1 to 4 Free Free Day 6 to 12 2,500 5,000 Day 5 to 12 4,000 8,000 Day 13 - 22 4,000 8,000 Day 13 - 22 5,000 10,000 Day 23 onwards 6,000 12,000 Day 23 onwards 7,000 14,000 We will continue to monitor the exchange rates and periodically adjust the tariff when there is significant upward or downward movement. -

South Africa Local Charges 2020/2021

Safmarine South Africa Local Charges 2020/2021 Version 3 – Effective 1st April 2020 Classification:safmarine.com Public TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Export Local Charges 2. Drop Off Charges 3. Import Local Charges 4. Export Detention Charges 5. Import Detention Charge 6. Demurrage Terms & Conditions 7. Demurrage Charges 8. Inland Surcharges website link to be announced In the event that any export Goods are stopped by the South African Revenue Service (“SARS”) or any other authority after the Goods have been delivered into the control of the Carrier, or are deemed in law to have been delivered into the control of the Carrier, then the Carrier may at the cost and risk of the Merchant arrange for the movement of the Goods in accordance with the instructions of SARS or such other authority. Once SARS or such other authority has granted release of the Goods for export, the Carrier may arrange for the Goods to be moved back into stacks for export at the sole risk and expense of the Merchant. The Carrier will under no circumstances be liable if the Goods miss the date of sailing as a result of the intervention by SARS or such other authority and the Goods will be exported on board the next available vessel subject of Clauses 8, 19 and 20 of the Carrier’s Bill of Lading Terms for Carriage. The Merchant indemnifies the Carrier, its employees, agents and/or sub-contractors as a result of their adhering to such instructions and in respect of consequent charges, Freight or expense incurred. All landside charges, Freight or expense, including but not limit to detention and demurrage, incurred by the Carrier on behalf of the Merchant after landing of the Goods and before release of the Goods, or incurred after the Goods are deemed to be under the Carrier’s control for export, shall be for the Merchant’s account and shall be payable on demand. -

Top 500 by Turnover 11-11-08

Rank Name of Company 1 BHP Billiton Plc 2 Anglo American Plc 3 SABMiller Plc 4 Sasol 5 The Bidvest Group 6 Old Mutual South Africa 7 Sanlam Ltd 8 Standard Bank Group Ltd 9 Imperial Holdings Ltd 10 FirstRand Ltd 11 Liberty Group Ltd 12 Telkom SA Ltd 13 MTN Group Ltd 14 Barloworld Ltd 15 ABSA Group Ltd 16 Anglo Platinum Ltd 17 Richemont Securities AG 18 Pick 'n Pay Stores Ltd 19 Shoprite Holdings Ltd 20 Nedbank Group Ltd 21 Vodacom Group (Pty) Ltd 22 Steinhoff International Holdings Ltd 23 Eskom 24 Sappi 25 Massmart Holdings Limited 26 Daimler Chrysler South Africa (Pty) Ltd 27 Impala Platinum Holdings Limited 28 BP Southern Africa (Pty) Ltd 29 Transnet Ltd 30 Dimension Data (Pty) Ltd 31 Investec Ltd 32 Mittal Steel South Africa (Pty) Ltd 33 Engen Petroleum Ltd 34 Toyota South Africa Motors (Pty) Ltd 35 Datatec Ltd 36 Aveng Ltd 37 Spar Group Ltd. 38 Metropolitan Holdings Ltd 39 Shell South Africa Energy (Pty) Ltd 40 Anglogold Ashanti Ltd 41 Goldfields Limited 42 McCarthy Ltd 43 Woolworths Holdings Ltd. 44 Network Healthcare Holdings Ltd t/a Netcare 45 Murray and Roberts Holdings Ltd 46 Remax of Southern Africa (Pty) Ltd 47 BHP Billiton Alumunium SA (Pty) Ltd 48 Allied Electronics Corporation Ltd 49 Tiger Brands Limited 50 Edgars Consolidated Stores Ltd 51 Safcor Freight (Pty) Ltd t/a Safcor Panalpina 52 Pam Golding Properties (Pty) Ltd 53 South African Airways (Pty) Ltd 54 Nampak Limited 55 Seeff Properties Services (Pty) Ltd 56 Momentum Group Ltd 57 Unitrans Holdings (Pty) Ltd 58 Kumba Iron Ore Ltd 59 Lonmin Plc 60 JD Group Limited 61 Santam -

29 November 2013

COLLEGE OF LAW AND MANAGEMENT STUDIES SCHOOL OF LAW UNIT OF MARITIME LAW AND MARITIME STUDIES THE REGULATION OF THE REMOVAL OF HAZARDOUS SHIPWRECKS IN SOUTH AFRICAN WATERS AND A DISCUSSION ON THE ADOPTION OF THE NAIROBI INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION ON THE REMOVAL OF WRECKS, 2007. STUDENT NAME : YINITA RAMSAKKAN STUDENT NUMBER : 208500262 Mini Dissertation submitted to the School of Law in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree Master of Laws in Maritime Law. SUPERVISOR : MR. V. SURBUN 29 NOVEMBER 2013. DECLARATION I, YINITA RAMSAKKAN, declare that: i. The research reported in this thesis, except where otherwise indicated, is my original work. ii. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or examination at any other university. iii. This thesis does not contain other persons’ data, pictures, graphs or other information, unless specifically acknowledged as being sourced from other persons. iv. This thesis does not contain other persons’ writing, unless specifically acknowledged as being sourced have been quoted, then: a. Their words have been re-written but the general information attributed to them has been referenced; b. Where their exact words have been used, their writing has been placed inside quotation marks, and referenced, v. Where I have reproduced a publication of which I am author, co-author or editor, I have indicated in detail which part of the publication was actually written by myself alone and have fully referenced such publications. vi. This thesis does not contain text, graphics or tables copied and pasted from the Internet, unless specifically acknowledged, and the source being detailed in the thesis and in the References sections. -

Reflecting on the Manifestations of a Cape Hip Hop Culture, 1983-2015

From Jamaica to the Cape Flets: Reflecting on the Manifestations of a Cape Hip Hop Culture, 1983-2015 by Adrian Van Wyk Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (History) in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Dr Chet James Paul Fransch March 2018 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis/dissertation, I declare that I understand what constitutes plagiarism, that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights, and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: March 2018 Copyright © 2018 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za ABSTRACT This dissertation seeks to reflect on the making of a Cape Town based Hip Hop culture with particular focus on the various manifestations which developed around the Cape Flats. This study investigates the importance of the numerous mediums in the development of a Hip Hop culture at the Cape from 1983 to 2015. Particular attention is given to audio-visual content such as film, music and music videos within the early formations of Hip Hop in the Cape. The audiences and performers who engaged with Hip Hop culture will be investigated. Furthermore, this study will follow the shift in the various forms of dissemination - from radio, television, to self-produced videos uploaded on digital media platforms on the internet. -

Woolworths Final

(Incorporated in the Republic of South Africa) (Registration number 1929/001986/06) Share code: WHL ISIN: ZAE000063863 (“Woolworths” or “the Company”) Circular to Woolworths Holdings Limited shareholders regarding: • a specific issue of ordinary shares in Woolworths Holdings Limited (“ordinary shares”) for cash to Woolworths (Proprietary) Limited; and incorporating: • a notice of general meeting; and • a form of proxy (blue) to be used by certificated and own name dematerialised shareholders only. 24 August 2009 Merchant bank and sponsor Corporate tax advisers Corporate law advisers edward nathan sonnenbergs CORPORATE INFORMATION AND ADVISERS Secretary and registered office Corporate law advisers Ms CL Lowe Taback and Associates (Proprietary) Limited Woolworths Holdings Limited (Registration number 2000/010434/07) (Registration number 1929/001986/06) 13 Eton Road Woolworths House Parktown 93 Longmarket Street Johannesburg, 2193 Cape Town, 8001 (PO Box 3334, Houghton, 2041) (PO Box 680, Cape Town, 8000) Corporate tax advisers Merchant bank and sponsor edward nathan sonnenbergs Inc Rand Merchant Bank (Registration number 2006/018200/21) (A division of FirstRand Bank Limited) 150 West Street (Registration number 1929/001225/06) Sandown 1 Merchant Place Sandton, 2196 Corner Fredman Drive and Rivonia Road (PO Box 783347, Sandton, 2146) Sandton, 2196 (PO Box 786273, Sandton, 2146) Transfer secretaries Computershare Investor Services (Proprietary) Limited (Registration number 2004/003647/07) Ground Floor 70 Marshall Street Johannesburg, 2001 (PO Box 61051, Marshalltown, 2107) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Corporate information and advisers Inside front cover Action required by shareholders 2 Important dates and times 3 Definitions 4 Circular to shareholders 7 1. Introduction 7 2. The transaction 7 3. Salient information on Woolworths 8 4. -

SOUTH AFRICAN SHIPPING PART 1: up to 1960

SOUTH AFRICAN SHIPPING PART ONE – TO 1960 1. EARLY YEARS During the Dutch and early British settlement at the Cape, local sailing vessels went up the west coast on fishing, sealing and guano-collecting expeditions, and as settlements grew along the southern African coast (especially in the later years of the British governing the Cape), they also moved small volumes of cargoes. Some of these small vessels (brigs, schooners, etc) were locally owned. The first steam coaster and several later steam coasters were British-owned, as were some vessels engaged in sealing and fishing. Several fishing vessels (sailing vessels and steamers) were owned locally, including some steam trawlers. Steam whalers operated out of Cape Town, Saldanha Bay and Port Natal, while Captain John Grindrod (based in Durban) conducted whaling operations in Mozambique and along the coast south of Port Natal. Gradually, local coastal shipowners began to emerge : The Barrys (c1859-1865; Breede River to Cape Town; sailing ships also traded on this route, some continuing to Britain with grain or hides and skins); Thesen (1869 – calling mainly at Knysna, Mossel Bay, Cape Town and west coast fishing harbours) This company continued trading under various ownerships until 1965 when it was bought by Safmarine and exchanged for shares in Unicorn Lines. Thesen’s schooner Albatross in which the family came to the Cape from Knysna in 1869. Photograph : Grindrod Collection Stephan Brothers (c.1880-1916 when bought by Mitchell Cotts; Cape Town-west coast); Smith, Webster & Co (1890-1917 when bought by Thesens; Cape Town-west coast); T.N. Price (c.1890-1896; taken over by Smith’s Coasters; Port Natal-Port Shepstone- Port St Johns). -

Safmarine (Pty) Ltd (“APMT”) the PROMOTION of ACCESS to INFORMATION MANUAL ("Manual")

Safmarine (Pty) Ltd (“APMT”) THE PROMOTION OF ACCESS TO INFORMATION MANUAL ("Manual") 1. PREAMBLE The Promotion of Access to Information Act, 2000 ("PAIA") came into operation on 9 March 2001. PAIA seeks, among other things, to give effect to the Constitutional right of access to any information held by the State or by any other person where such information is required for the exercise or protection of any right and gives natural and juristic persons the right of access to records held by either a private or public body, subject to certain limitations, in order to enable them to exercise or protect their rights. Where a request is made in terms of PAIA to a private body, that private body must disclose the information if the requester is able to show that the record is required for the exercise or protection of any rights, and provided that no grounds of refusal contained in PAIA are applicable. PAIA sets out the requisite procedural issues attached to information requests. Section 51 of PAIA obliges private bodies to compile a manual to enable a person to obtain access to information held by such private body and stipulates the minimum requirements that the manual has to comply with. This Manual constitutes APMT’s PAIA manual. This Manual is compiled in accordance with section 51 of PAIA as amended by the Protection of Personal Information Act, 2013 ("POPIA"), which gives effect to everyone’s Constitutional right to privacy. POPIA promotes the protection of personal information processed by public and private bodies, including certain conditions so as to establish minimum requirements for the processing of personal information. -

Create by Pagemanager

April 1986 An official Journal of the South African Institute of Electrical Engineers 'n Amptelike Joernaal van die Suid Af rikaanse Instituut van Elektriese Ingenieurs South Africa's most concentrated form of energy. ' V1. .1 ' o " I can take time off with peace of mind because my friends work for me. Let me tell you about my 'SMART' friends - who are proud members of large families - there's... OVERLOAD POWER MONITOR, he's an inquisitive young chap with a family back ground dating back many generations. LEVEL CONTROL, a sensitive type who's strictly on the level. INFRA-RED LIGHT BEAM, a robust character who's straight to the point. I call him 'Cats Eyes' because he sees in the dark. TIMER, a punctual pal who never lets me down, but what a smooth operator. ^ PROXIMITY SENSOR, a bright stalwart you phone Rhomberg Electronics like I did." but occasionally difficult to get close to. Designers and Manufacturers And of course COUNTER, my accountant of Electronic Automation who enjoys saving me money. RHOMBERO Equipment The ancestral home of these 'FRIENDS' 8 Honeywell Road, Retreat, 7945, Cape Town. Telephone (021) 75-1114 believe that the customer is King and that Telex 52-6428 SA. electronics Johannesburg. Telephone (011)339-1956 service reliability and availability are goals Telex 42-4652 SA. to be constantly strived for. LASTING FRIENDS YOU CAN RELY ON elehtran An Official Journal of The South African Institute of Electrical Engineers 'n Amptelike Joemaal van die Suid-Afrikaanse Instituut van Elektriese Ingenieurs Head Office PO Box 61019 Marshalltown 2107 Transvaal Telephone: (011)832-2177/4 Telegraphic Address: FARAD elehtran SAIEE Office Bearers President: APRIL 1986 A. -

Shipbreaking # 49 – October 2017 Alert on Towing Operations

Shipbreaking Bulletin of information and analysis on ship demolition # 49, from July 1 to September 30, 2017 October 26, 2017 Content Alert on towing operations 2 Container ship 33 Car carrier 77 (Transocean Winner, Maersk Searcher Reefer 44 City of Antwerp, the escapee 77 and Maersk Shipper, Pipelife Norge AS) Ro Ro 47 from scrapping in Europe Anniversaries: Brazil, Mexiqco 5 Oil tanker 48 Heavy load carrier 80 Demolition in Ecuador 7 Chemical tanker 58 Ofshore supply vessel 81 3rd quarter overview : tankers and 9 Gas tanker 59 Research vessel 85 Bangladesh nos 1 Combinated carrier 61 The END: Shen Neng 1, all of 86 Ferry/ passenger ship 13 Bulker 62 that to gain 2 miles General cargo carrier 17 Pusher tug-barge 76 Factory ship 32 Cement carrier 76 Sources 89 December 22, 2016, shortly after midnight, the Maersk Searcher is sinking (left). Source : private photo. Robin des Bois - 1 - Shipbreaking # 49 – October 2017 Alert on towing operations In quick succession, Northern European countries sent floating equipment, towed cargoes, and decommissioned vessels to the Mediterranean. They did not reach their destination or spread pollution and other harmful substances along the way. 1- Transocean Winner Transocean Winner, August 2016. © Mark Macleod © Robin des Bois The Transocean Winner is a semi-submersible platform, 30-year old at the time of the accident. It is registered in the Marshall Islands. Its owner, Transocean Offshore International Ventures Limited, based in George Town, Cayman Islands and subsidiary of Transocean Ltd based in Zug, Switzerland, decided to get rid of the platform in light of its age and of the economic situation.