The Virtual Sphere 2.0: the Internet, the Public Sphere, and Beyond 230 Zizi Papacharissi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FCC-06-11A1.Pdf

Federal Communications Commission FCC 06-11 Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Annual Assessment of the Status of Competition ) MB Docket No. 05-255 in the Market for the Delivery of Video ) Programming ) TWELFTH ANNUAL REPORT Adopted: February 10, 2006 Released: March 3, 2006 Comment Date: April 3, 2006 Reply Comment Date: April 18, 2006 By the Commission: Chairman Martin, Commissioners Copps, Adelstein, and Tate issuing separate statements. TABLE OF CONTENTS Heading Paragraph # I. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................. 1 A. Scope of this Report......................................................................................................................... 2 B. Summary.......................................................................................................................................... 4 1. The Current State of Competition: 2005 ................................................................................... 4 2. General Findings ....................................................................................................................... 6 3. Specific Findings....................................................................................................................... 8 II. COMPETITORS IN THE MARKET FOR THE DELIVERY OF VIDEO PROGRAMMING ......... 27 A. Cable Television Service .............................................................................................................. -

News Headline Tone in International Coverage of North Korea's September 2017 Nuclear Test

Athens Journal of Mass Media and Communications- Volume 5, Issue 1 – Pages 1-16 A Rogue Nation: News Headline Tone in International Coverage of North Korea’s September 2017 Nuclear Test By Butler Cain & Kristina Drumheller† On September 3, 2017, North Korea underwent its sixth nuclear test despite expectations of denuclearization. News headlines from six international news sources were analyzed for journalistic tone related to the nuclear test. As with previous research on earlier tests, headlines were primarily neutral or negative regardless of the news source. Given that 60% of people only read the headlines, and a similar number share news stories on social media based on headline, examining journalistic tone in headlines during international crises is worthwhile. Keywords: Korea, nuclear, headline, tone, journalism. Introduction News coverage of North Korea’s continued thwarting of denuclearization efforts has often ranged from neutral reporting of events to negative condemnation with little to no positive commentary (Cain & Drumheller, 2014). North Korea’s sixth nuclear test on September 3, 2017, brought variations in headlines from news organizations around the world. News headlines might be all that is read of a news story as headlines are highlighted in email briefs and social media shares. This study analyzes the news headlines from six international broadcasters on the day of the detonation and examines them for journalistic tone to assess agenda setting trends set by the limited but salient information a headline provides. The relationship the United States has with North Korea has long been one of proximity through maintaining a base in South Korea and policy demand in the form of CVID (complete, verifiable, and irreversible denuclearization; Anderson, 2017). -

The Next Digital Decade Essays on the Future of the Internet

THE NEXT DIGITAL DECADE ESSAYS ON THE FUTURE OF THE INTERNET Edited by Berin Szoka & Adam Marcus THE NEXT DIGITAL DECADE ESSAYS ON THE FUTURE OF THE INTERNET Edited by Berin Szoka & Adam Marcus NextDigitalDecade.com TechFreedom techfreedom.org Washington, D.C. This work was published by TechFreedom (TechFreedom.org), a non-profit public policy think tank based in Washington, D.C. TechFreedom’s mission is to unleash the progress of technology that improves the human condition and expands individual capacity to choose. We gratefully acknowledge the generous and unconditional support for this project provided by VeriSign, Inc. More information about this book is available at NextDigitalDecade.com ISBN 978-1-4357-6786-7 © 2010 by TechFreedom, Washington, D.C. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. Cover Designed by Jeff Fielding. THE NEXT DIGITAL DECADE: ESSAYS ON THE FUTURE OF THE INTERNET 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword 7 Berin Szoka 25 Years After .COM: Ten Questions 9 Berin Szoka Contributors 29 Part I: The Big Picture & New Frameworks CHAPTER 1: The Internet’s Impact on Culture & Society: Good or Bad? 49 Why We Must Resist the Temptation of Web 2.0 51 Andrew Keen The Case for Internet Optimism, Part 1: Saving the Net from Its Detractors 57 Adam Thierer CHAPTER 2: Is the Generative -

Modeling Internet-Based Citizen Activism and Foreign Policy

MODELING INTERNET-BASED CITIZEN ACTIVISM AND FOREIGN POLICY: The Islands Dispute between China and Japan TOMONOBU KUMAHIRA Primary Thesis Advisor: Professor Jordan Branch Department of Political Science Secondary Thesis Advisor: Professor Kerry Smith Department of History Honors Seminar Instructor: Professor Claudia Elliott The Watson Institute for International Studies SENIOR THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors in International Relations BROWN UNIVERSITY PROVIDENCE, RI MAY 2015 © Copyright 2015 by Tomonobu Kumahira ABSTRACT How can citizens utilize the Internet to influence foreign policymaking? Optimists emphasize the Internet’s great potential to empower citizens, while pessimists underscore the persistent dominance of conventional actors in shaping diplomacy. These conceptual debates fail to build analytical models that theorize the mechanisms through which citizen activism impacts foreign policymaking in the Internet era. Focusing on the interactions between “old” institutions and new practices enabled by technology, I argue that Internet-based citizen activists are using multiple and evolving strategies to engage with the conventional media and policymakers. My Hybrid Model provides an analytical framework with which scholars can describe new forms of non-electoral representation by citizen movements, while challenging foreign policy decision making theories established before the social media. My model traces the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands dispute between China and Japan, in which nationalist campaigns online and offline have fueled a series of confrontations since 2005. Presenting practical implications for foreign policymakers and the conventional media to respond to the transformation, this Hybrid Model also helps citizens play a more active role in international relations. In conclusion, I explore the analogy between the Internet and past innovations in communication technologies to shed light on the future of the Internet and politics. -

DIRECTV® PRIVATE VIEWING PACKAGES and RATES

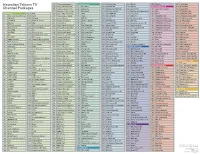

DIRECTV® PRIVATE VIEWING PACKAGES and RATES Customers must subscribe to one of the following base programming packages in order to add on any additional service(s): BUSINESS XTRA PACK, BUSINESS ENTERTAINMENTTM PACK, BUSINESS SELECTTM PACK or COMERCIAL ÓPTIMO MÁS PACK. Base Programming packages include Local channels and HD programming where available. 140+ BUSINESS XTRA PACK Channels A&E HD Disney Channel (East) HD HSN RFD-TV AMC HD Disney Channel (West) IFC HD Science HD American Heroes Disney Junior HD INSP SEC Network HD America’s Auction Network Disney XD HD Investigation Discovery HD Shopping Network Animal Planet HD DIY Network HD ION Television (East) HD Son Life Broadcasting Network Aqui †† E! HD ION Television (West) Spike HD AUDIENCE® HD Enlace†† Jewelry Television Sportsman Channel AXS TV (HD only) HD ESPN HD Jewish Life Television SundanceTV HD BabyFirstTV ESPN2 HD Lifetime HD Syfy HD BBC America HD ESPNEWS HD Link TV TBS HD BBC World News (HD only) HD ESPNU HD Liquidation Channel TCM HD BET HD EVINE LMN HD TCT Network Bloomberg TV HD EWTN Logo TeenNick Bravo HD Food Network HD MAVTV Tennis Channel HD BTN FOX Business Network HD MLB Network HD TLC HD BYUtv FOX News Channel HD MSNBC HD TNT HD CANAL ONCE †† FOX Sports 1 HD MTV HD Travel Channel HD Cartoon Network (East) HD FOX Sports 2 HD MTV2 HD Trinity Broadcasting Network (TBN) Cartoon Network (West) Freeform HD NASA TV truTV HD CBS Sports Network HD Free Speech TV Nat Geo WILD HD TV Land HD Centric Fuse National Geographic HD TV One Celebrity Shopping Network Fusion (HD only) HD NBA TV HD TVG CMT HD FX HD NBC Sports Network HD UniMás HD CNBC HD FX Movie Channel NBC Universo Univision (East) HD CNBC World FXX HD NFL Network HD UP CNN HD fyi, HD NHL Network HD Uplift Comedy Central HD Galavisión HD Nick Jr. -

The Digital Divide: the Internet and Social Inequality in International Perspective

http://www.diva-portal.org This is the published version of a chapter published in The Digital Divide: The Internet and Social Inequality in International Perspective. Citation for the original published chapter: Meinrath, S., Losey, J., Lennett, B. (2013) Afterword. Internet Freedom, Nuanced Digital Divide, and the Internet Craftsman. In: Massimo Ragnedda and Glenn W. Muschert (ed.), The Digital Divide: The Internet and Social Inequality in International Perspective (pp. 309-316). London: Routledge Routledge advances in sociology N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published chapter. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:su:diva-100423 The Digital Divide This book provides an in-depth comparative analysis of inequality and the stratification of the digital sphere. Grounded in classical sociological theories of inequality, as well as empirical evidence, this book defines “the digital divide” as the unequal access and utility of internet communications technologies and explores how it has the potential to replicate existing social inequalities, as well as create new forms of stratification. The Digital Divide examines how various demographic and socio-economic factors including income, education, age and gender, as well as infrastructure, products and services affect how the internet is used and accessed. Comprised of six parts, the first section examines theories of the digital divide, and then looks in turn at: • Highly developed nations and regions (including the USA, the EU and Japan); • Emerging large powers (Brazil, Russia, India, China); • Eastern European countries (Estonia, Romania, Serbia); • Arab and Middle Eastern nations (Egypt, Iran, Israel); • Under-studied areas (East and Central Asia, Latin America, and sub-Saharan Africa). -

Hawaiian Telcom TV Channel Packages

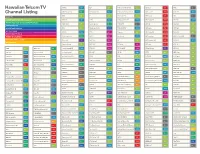

Hawaiian Telcom TV 604 Stingray Everything 80’s ADVANTAGE PLUS 1003 FOX-KHON HD 1208 BET HD 1712 Pets.TV 525 Thriller Max 605 Stingray Nothin but 90’s 21 NHK World 1004 ABC-KITV HD 1209 VH1 HD MOVIE VARIETY PACK 526 Movie MAX Channel Packages 606 Stingray Jukebox Oldies 22 Arirang TV 1005 KFVE (Independent) HD 1226 Lifetime HD 380 Sony Movie Channel 527 Latino MAX 607 Stingray Groove (Disco & Funk) 23 KBS World 1006 KBFD (Korean) HD 1227 Lifetime Movie Network HD 381 EPIX 1401 STARZ (East) HD ADVANTAGE 125 TNT 608 Stingray Maximum Party 24 TVK1 1007 CBS-KGMB HD 1229 Oxygen HD 382 EPIX 2 1402 STARZ (West) HD 1 Video On Demand Previews 126 truTV 609 Stingray Dance Clubbin’ 25 TVK2 1008 NBC-KHNL HD 1230 WE tv HD 387 STARZ ENCORE 1405 STARZ Kids & Family HD 2 CW-KHON 127 TV Land 610 Stingray The Spa 28 NTD TV 1009 QVC HD 1231 Food Network HD 388 STARZ ENCORE Black 1407 STARZ Comedy HD 3 FOX-KHON 128 Hallmark Channel 611 Stingray Classic Rock 29 MYX TV (Filipino) 1011 PBS-KHET HD 1232 HGTV HD 389 STARZ ENCORE Suspense 1409 STARZ Edge HD 4 ABC-KITV 129 A&E 612 Stingray Rock 30 Mnet 1017 Jewelry TV HD 1233 Destination America HD 390 STARZ ENCORE Family 1451 Showtime HD 5 KFVE (Independent) 130 National Geographic Channel 613 Stingray Alt Rock Classics 31 PAC-12 National 1027 KPXO ION HD 1234 DIY Network HD 391 STARZ ENCORE Action 1452 Showtime East HD 6 KBFD (Korean) 131 Discovery Channel 614 Stingray Rock Alternative 32 PAC-12 Arizona 1069 TWC SportsNet HD 1235 Cooking Channel HD 392 STARZ ENCORE Classic 1453 Showtime - SHO2 HD 7 CBS-KGMB 132 -

Hawaiian Telcom TV Channel Listing

Hawaiian Telcom TV CMT HD 1200 DIY 234 FOX Sports Prime Ticket 82 HBO East 501 KFVE 13 Channel Listing CMT Pure Country 201 DIY Network HD 1234 FOX Sports Prime Ticket HD 1082 HBO East HD 1501 KFVE HD* 1013 CNBC 176 E! 240 FOX Sports West 81 HBO Family 507 KHII 5 BASIC TV ADVANTAGE (INCLUDES BASIC TV) CNBC HD 1176 E! HD 1240 FOX Sports West HD 1081 HBO Family HD 1507 KHII HD* 1005 ADVANTAGE PLUS (INCLUDES ADVANTAGE) CNBC World 177 Eleven Sports 91 FOX-KHON 3 HBO HD 1502 KHJZ 93.9 665 ADVANTAGE HD ADVANTAGE PLUS HD CNN 172 Eleven Sports HD 1091 FOX-KHON HD* 1003 HBO Latino 512 KHPR 88.1 661 HD PLUS PACK *HD SERVICE WITH BASIC TV PACK includes these channels. CNN HD 1172 EPIX 381 Freeform 122 HBO Latino HD 1512 Kid’s Stuff 627 MOVIE VARIETY PACK CNN International 304 EPIX 2 382 Freeform HD 1122 HBO Signature 505 KIKU-TV (Jpn/UPN) 20 PREMIUM CHANNELS INTERNATIONAL / OTHER Comedy.TV 1707 EPIX 2 HD 1382 FX 124 HBO Signature HD 1505 KIKU HD* 1020 PAY PER VIEW Comedy Central 142 EPIX 3 HD 1383 FX Movie 398 HBO Zone 511 KINE 105.1 675 A&E 129 BET Soul 211 Comedy Central HD 1142 EPIX HD 1381 FX Movie HD 1398 HDNet Movies 1703 KIPO 89.3 662 A&E HD 1129 Big Ten Network 79 Cooking Channel 235 ESCAPE 46 FX HD 1124 HGTV 232 KKEA 1420 678 ABC-KITV 4 Big Ten Network HD 1079 Cooking Channel HD 1235 ESPN 70 FXX 110 HGTV HD 1232 KORL 101.1 672 ABC-KITV HD* 1004 Bloomberg TV 171 COZI 15 ESPN Classic Sports 71 FXX HD 1110 History Channel 133 KPHW 104.3 674 Action Max 523 Bloomberg TV HD 1171 Crime & Investigation 303 ESPN HD 1070 FYI 300 History Channel HD -

Security and Privacy for Outsourced Computations. Amrit Kumar

Security and privacy for outsourced computations. Amrit Kumar To cite this version: Amrit Kumar. Security and privacy for outsourced computations.. Cryptography and Security [cs.CR]. Université Grenoble Alpes, 2016. English. NNT : 2016GREAM093. tel-01687732 HAL Id: tel-01687732 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01687732 Submitted on 18 Jan 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THESE` Pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR DE L’UNIVERSITE´ DE GRENOBLE Specialit´ e´ : Informatique Arretˆ e´ ministerial´ : 7 aoutˆ 2006 Present´ ee´ par Amrit Kumar These` dirigee´ par Pascal Lafourcade et codirigee´ par Cedric´ Lauradoux prepar´ ee´ au sein d’Equipe´ Privatics, Inria, Grenoble-Rhoneˆ Alpes et de l’Ecole´ Doctorale MSTII Security and Privacy of Hash-Based Software Applications These` soutenue publiquement le 20 octobre, 2016, devant le jury compose´ de : Mr. Refik Molva Professeur, Eurecom, President´ Mr. Gildas Avoine Professeur, INSA Rennes, Rapporteur Mr. Sebastien´ Gambs Professeur, Universite´ du Quebec´ a` Montreal,´ Rapporteur Mr. Kasper B. Rasmussen Professeur associe,´ University of Oxford, Examinateur Ms. Reihaneh Safavi-Naini Professeur, University of Calgary, Examinatrice Mr. Pascal Lafourcade Maˆıtre de Conference,´ Universite´ d’Auvergne, Directeur de these` Mr. -

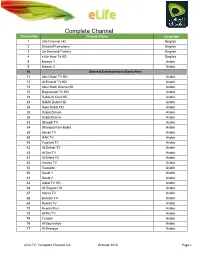

Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1

Complete Channel Channel No. List Channel Name Language 1 Info Channel HD English 2 Etisalat Promotions English 3 On Demand Trailers English 4 eLife How-To HD English 8 Mosaic 1 Arabic 9 Mosaic 2 Arabic 10 General Entertainment Starts Here 11 Abu Dhabi TV HD Arabic 12 Al Emarat TV HD Arabic 13 Abu Dhabi Drama HD Arabic 15 Baynounah TV HD Arabic 22 Dubai Al Oula HD Arabic 23 SAMA Dubai HD Arabic 24 Noor Dubai HD Arabic 25 Dubai Zaman Arabic 26 Dubai Drama Arabic 33 Sharjah TV Arabic 34 Sharqiya from Kalba Arabic 38 Ajman TV Arabic 39 RAK TV Arabic 40 Fujairah TV Arabic 42 Al Dafrah TV Arabic 43 Al Dar TV Arabic 51 Al Waha TV Arabic 52 Hawas TV Arabic 53 Tawazon Arabic 60 Saudi 1 Arabic 61 Saudi 2 Arabic 63 Qatar TV HD Arabic 64 Al Rayyan HD Arabic 67 Oman TV Arabic 68 Bahrain TV Arabic 69 Kuwait TV Arabic 70 Kuwait Plus Arabic 73 Al Rai TV Arabic 74 Funoon Arabic 76 Al Soumariya Arabic 77 Al Sharqiya Arabic eLife TV : Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1 Complete Channel 79 LBC Sat List Arabic 80 OTV Arabic 81 LDC Arabic 82 Future TV Arabic 83 Tele Liban Arabic 84 MTV Lebanon Arabic 85 NBN Arabic 86 Al Jadeed Arabic 89 Jordan TV Arabic 91 Palestine Arabic 92 Syria TV Arabic 94 Al Masriya Arabic 95 Al Kahera Wal Nass Arabic 96 Al Kahera Wal Nass +2 Arabic 97 ON TV Arabic 98 ON TV Live Arabic 101 CBC Arabic 102 CBC Extra Arabic 103 CBC Drama Arabic 104 Al Hayat Arabic 105 Al Hayat 2 Arabic 106 Al Hayat Musalsalat Arabic 108 Al Nahar TV Arabic 109 Al Nahar TV +2 Arabic 110 Al Nahar Drama Arabic 112 Sada Al Balad Arabic 113 Sada Al Balad -

Global Information Society Watch 2009 Report

GLOBAL INFORMATION SOCIETY WATCH (GISWatch) 2009 is the third in a series of yearly reports critically covering the state of the information society 2009 2009 GLOBAL INFORMATION from the perspectives of civil society organisations across the world. GISWatch has three interrelated goals: SOCIETY WATCH 2009 • Surveying the state of the field of information and communications Y WATCH technology (ICT) policy at the local and global levels Y WATCH Focus on access to online information and knowledge ET ET – advancing human rights and democracy I • Encouraging critical debate I • Strengthening networking and advocacy for a just, inclusive information SOC society. SOC ON ON I I Each year the report focuses on a particular theme. GISWatch 2009 focuses on access to online information and knowledge – advancing human rights and democracy. It includes several thematic reports dealing with key issues in the field, as well as an institutional overview and a reflection on indicators that track access to information and knowledge. There is also an innovative section on visual mapping of global rights and political crises. In addition, 48 country reports analyse the status of access to online information and knowledge in countries as diverse as the Democratic Republic of Congo, GLOBAL INFORMAT Mexico, Switzerland and Kazakhstan, while six regional overviews offer a bird’s GLOBAL INFORMAT eye perspective on regional trends. GISWatch is a joint initiative of the Association for Progressive Communications (APC) and the Humanist Institute for Cooperation with -

Licensing of Third Generation (3G) Mobile: Briefing Paper

LICENSING OF THIRD GENERATION (3G) MOBILE: BRIEFING PAPER1 1 This paper was prepared by Dr Patrick Xavier of the School of Business, Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne, Australia ([email protected]) ahead of the ITU Workshop on licensing 3G Mobile, to be held on 19-21 September 2001 in Geneva. The author wishes to thank Lara Srivastava, Dr Tim Kelly and Audrey Selian of the ITU and John Bahtsevanoglou of the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission for significant contributions relating to the preparation of this paper. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the ITU or its membership. 3G Briefing Paper TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction................................................................................................................................................ 5 1.1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Structure of the paper ....................................................................................................................... 6 2 Technical issues in the evolution to third-generation networks................................................................. 6 2.1 Standardization issues ...................................................................................................................... 7 2.2 The migration path from 2G to 3G..................................................................................................