Happiness Is a Small, Warm Off-Roader

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Auto Parts Canadian Settlements

AUTO PARTS CANADIAN SETTLEMENTS Settlement Amount Action Settled Defendant(s) (CDN) Approved Hearing Date (unless otherwise indicated) Air Conditioning DENSO Corporation et al $4,943,000 Feb 28/20 n/a Systems Panasonic Corporation et al $126,000 n/a May 13/21 Marelli Corporation (f/k/a $878,935.99 n/a May 13/21 Calsonic Kansei Corporation) et al Air Flow Meters Hitachi, Ltd., et al $725,000 May 1/17 n/a DENSO Corporation et al $150,000 Feb 28/20 n/a Alternators Hitachi, Ltd., et al $950,000 May 1/17 n/a Mitsubishi Electric $2,200,000 Sept 21/18 n/a Corporation et al DENSO Corporation et al $5,120,000 Feb 28/20 n/a ATF Warmers and Oil T.RAD Co., Ltd. et al $113,476.33 Jun 19/18 n/a Coolers DENSO Corporation et al $302,000 Feb 28/20 n/a Marelli Corporation (f/k/a $64,867.52 n/a May 13/21 Calsonic Kansei Corporation) et al Autolights Mitsuba Corporation et al $150,000 May 28/19 n/a Koito Manufacturing Co., $3,666,000 Aug 27/20 n/a Ltd. et al. Automotive Brake Hitachi Metals, Ltd. et al $175,000 Feb 28/20 n/a Hoses Toyoda Gosei Co., Ltd. $97,419.03 Aug 27/20 n/a Automotive Constant- Toyo Tire & Rubber Co., $258,969.19 Aug 27/20 n/a Velocity-Joint Boot Ltd. et al Products Toyoda Gosei Co., Ltd. $105,846.66 Aug 27/20 n/a Automotive Exhaust DENSO Corporation et al $150,000 Feb 28/20 n/a Systems NGK Spark Plugs (U.S.A.), $66,510 Feb 28/20 n/a Inc., et al Eberspächer Gruppe GmbH $190,000 Aug 27/20 n/a & Co. -

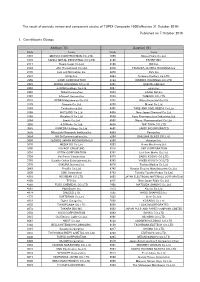

Published on 7 October 2016 1. Constituents Change the Result Of

The result of periodic review and component stocks of TOPIX Composite 1500(effective 31 October 2016) Published on 7 October 2016 1. Constituents Change Addition( 70 ) Deletion( 60 ) Code Issue Code Issue 1810 MATSUI CONSTRUCTION CO.,LTD. 1868 Mitsui Home Co.,Ltd. 1972 SANKO METAL INDUSTRIAL CO.,LTD. 2196 ESCRIT INC. 2117 Nissin Sugar Co.,Ltd. 2198 IKK Inc. 2124 JAC Recruitment Co.,Ltd. 2418 TSUKADA GLOBAL HOLDINGS Inc. 2170 Link and Motivation Inc. 3079 DVx Inc. 2337 Ichigo Inc. 3093 Treasure Factory Co.,LTD. 2359 CORE CORPORATION 3194 KIRINDO HOLDINGS CO.,LTD. 2429 WORLD HOLDINGS CO.,LTD. 3205 DAIDOH LIMITED 2462 J-COM Holdings Co.,Ltd. 3667 enish,inc. 2485 TEAR Corporation 3834 ASAHI Net,Inc. 2492 Infomart Corporation 3946 TOMOKU CO.,LTD. 2915 KENKO Mayonnaise Co.,Ltd. 4221 Okura Industrial Co.,Ltd. 3179 Syuppin Co.,Ltd. 4238 Miraial Co.,Ltd. 3193 Torikizoku co.,ltd. 4331 TAKE AND GIVE. NEEDS Co.,Ltd. 3196 HOTLAND Co.,Ltd. 4406 New Japan Chemical Co.,Ltd. 3199 Watahan & Co.,Ltd. 4538 Fuso Pharmaceutical Industries,Ltd. 3244 Samty Co.,Ltd. 4550 Nissui Pharmaceutical Co.,Ltd. 3250 A.D.Works Co.,Ltd. 4636 T&K TOKA CO.,LTD. 3543 KOMEDA Holdings Co.,Ltd. 4651 SANIX INCORPORATED 3636 Mitsubishi Research Institute,Inc. 4809 Paraca Inc. 3654 HITO-Communications,Inc. 5204 ISHIZUKA GLASS CO.,LTD. 3666 TECNOS JAPAN INCORPORATED 5998 Advanex Inc. 3678 MEDIA DO Co.,Ltd. 6203 Howa Machinery,Ltd. 3688 VOYAGE GROUP,INC. 6319 SNT CORPORATION 3694 OPTiM CORPORATION 6362 Ishii Iron Works Co.,Ltd. 3724 VeriServe Corporation 6373 DAIDO KOGYO CO.,LTD. 3765 GungHo Online Entertainment,Inc. -

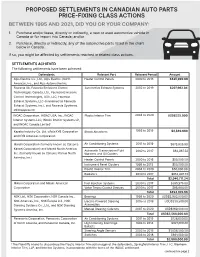

Auto Parts Price-Fixing Class Actions Between 1995 and 2021, Did You Or Your Company

PROPOSED SETTLEMENTS IN CANADIAN AUTO PARTS PRICE-FIXING CLASS ACTIONS BETWEEN 1995 AND 2021, DID YOU OR YOUR COMPANY: 1. Purchase and/or lease, directly or indirectly, a new or used automotive vehicle in Canada or for import into Canada; and/or 2. Purchase, directly or indirectly, any of the automotive parts listed in the chart below in Canada. If so, you might be affected by settlements reached in related class actions. SETTLEMENTS ACHIEVED The following settlements have been achieved: Defendants Relevant Part Relevant Period Amount Alps Electric Co., Ltd., Alps Electric (North Heater Control Panels 2000 to 2016 $425,000.00 America), Inc., and Alps Automotive Inc. Faurecia SA, Faurecia Emissions Control Automotive Exhaust Systems 2002 to 2019 $207,962.04 Technologies Canada, Ltd., Faurecia Emissions Control Technologies, USA, LLC, Faurecia Exhaust Systems, LLC (misnamed as Faurecia Exhaust Systems, Inc.), and Faurecia Systèmes d’Èchappement INOAC Corporation, INOAC USA, Inc., INOAC Plastic Interior Trim 2004 to 2020 USD$325,000 Interior Systems LLC, INOAC Interior Systems LP, and INOAC Canada Limited1 Kayaba Industry Co. Ltd. d/b/a KYB Corporation Shock Absorbers 1995 to 2019 $4,840,000 and KYB Americas Corporation Marelli Corporation (formerly known as Calsonic Air Conditioning Systems 2001 to 2019 $878,935.99 Kansei Corporation) and Marelli North America, Automatic Transmission Fluid 2002 to 2017 $64,867.52 Inc. (formerly known as Calsonic Kansei North Warmers and Oil Coolers America, Inc.) Heater Control Panels 2000 to 2016 $50,000.00 -

(DAT-3) Datsun 240Z-HSR 2015

HSR Supplemental Regulations (DAT-3): (last revised 12/28/14) Datsun (Nissan) 240Z (1969-1973) HSR Group 3 Class: HP7 Historic Production Category (SCCA C/P) The following cars are covered under these regulations: 1969-1973 Datsun 240Z (2393cc, SOHC I-6) Note: chassis may be updated or backdated to achieve proper specifications ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Engines: .047” (1.2mm) maximum overbore allowed L24 (2393cc) Bore x stroke 3.2677” x 2.90” Head material……….aluminum Block material………cast iron Carburetion…………. (3) 44PHH Mikuni or (2) Hitachi HJG 46W or SU equivalent. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Transmissions: Datsun/Nissan…………………….4 or 5 speeds, ratios free ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Chassis: 2 door, uni-body coupe, steel body, independent rear suspension Wheelbase: 90.7” Track dimension: front…54”, +/- 2” rear…54”, +/- 2” Wheels: 7” x 14” Brakes, pre-1973 (CP): 11” discs, iron calipers; front 9” drums; rear Suspension: MacPherson strut w/coil spring; front hydraulic strut w/coil spring; rear ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Official -

Multi Technology System INC. Company Profile

Multi Technology System INC. Company Profile Best technology, automation systems, Quality and safety. Solutions for Automation To provide customers excellent-quality Products and service Table of Contents 1 GREETINGS 2 BRIEF HISTORY 3 COMPANY BROCHURE 4 M’Tech System Demo Staion 5 CUSTOMER 6 MAJOR ITEM 7 MAJOR PROJECTS To manufacture 8 PURGE TESTING PROCEDURE best-quality products 9 INSPECTION that customers rely on 10 QUALITY Greetings The First step“ of control starts with the precise measurement of value. Since it’s establishment in 2002, MTECH has been engaged in manufacturing of the PLC & HMI System and Air Purge Panel. We are realizing defect-free production through supplying and accurate and effcient system to various area industrial work places and the latest equipment MTECH has developed it’s own technology and quality to meet international standards and will continue to find new way for better the service to our customers. ALL of MTECH employees are committed to serve their customers with integrity and diligence. We will try it’s utmost until it can solve problem in any place and anytime at the request of customers. Thank you. President Suck Chul KANG BRIEF HISTORY Going to get The Certificate INNOBIZ Obtained The Certificate of R&D Center M'TECH System Factoy Extension Rockwell RcSI (AB PLC) Certificate Samsung Total Certificate Headquarter has just acquired a new office for the extent and move KGS Certificate for Technical Capability & Production Organization SK Energy Certificate Venture Business Certificate Obtained The Certificate of ISO 9001:2000 Established M Tech System INC. COMPANY BROCHURE HEAD OFFICE FACTORY COMPANY BROCHURE The conference room is provided for your convenience and are equipped with everything they could to make our customers feel welcome. -

Vehicle Industry Review and Outlook Alixpartners Proprietary

Vehicle Industry Review and Outlook AlixPartners Proprietary Agenda State of the Industry (OEMs/suppliers) Troubled Suppliers Globalization/China Quality/Warranty Entry level segment Summary 2 AlixPartners Proprietary AlixPartners - Introduction 3 AlixPartners Proprietary AlixPartners Has Worked With Vehicle Manufacturers and Suppliers Globally AZ Automotive Corp. 4 AlixPartners Proprietary AlixPartners Offers Three Key Differentiators Experienced staff, with practical, real-world experience Small Senior Teams Small Senior Teams Significant senior leadership time High company ownership Components of compensation based on results AlignedAligned IncentivesIncentives Results are driven to the bottom line Success is definitive and measurable Experienced implementers ProvenProven ResultsResults Culture and approach built on speed and urgency Results focus—not reports 5 AlixPartners Proprietary The 2006 AlixPartners Automotive Benchmarking Survey Includes 104 Suppliers, 22 Auto and 18 Heavy Truck OEMs Ford, General BMW, DaimlerChrysler, Fiat, Chongqing Changan, Dongfeng, Fuji, Honda, Motors Peugeot, Porsche, Renault, Hyundai, Isuzu, KIA, Mazda, Mitsubishi, Volkswagen Nissan, Shanghai Automotive, Suzuki, Toyota Caterpillar, Deere, Navistar, CNH, Man AG, Scania, Volvo Ashok Leyland, Changchun Faw-Sihuan, Hino Oshkosh Truck, Paccar Motors, Inner Mongolia North Hauler, Komatsu, Mahindra & Mahindra, Mitsubishi Heavy, Tata, Yangzhou Yaxing AmericasAmericas EuropeEurope AsiaAsia American Axle, ArvinMeritor, Autoliv, Bosch Automotive, -

Mikuni Hsr40 Hsr42 Hsr45 Jet Assortments

MIKUNI CARBURETOR JETS MIKUNI 4/042 TYPE MAIN JET SHOP KITS MIKUNI VM28/486 TYPE K&L carries a variety of Mikuni type main PILOT JETS jets to fit most popular motorcycles. These Sold pk/5. TOOLS high precision brass jets meet OEM 18-4739 #15 18-4749 #30 specifications. Made in Japan. 18-4742 #17.5 18-4750 #35 KITS INCLUDE QTY-1/PK(of 5) of the sizes listed. #20 #40 SHOP EQUIPMENT 18-4743 18-4751 Each jet size also Sold in Pk/5, (see below). 18-4745 #22.5 18-4752 #45 18-4747 #25 18-4753 #50 18-9202 18-4748 #27.5 TYPE JET K&L P/N QTY/JET JET SIZES INCREMENTS Mikuni Large Hex 18-9201 Pk/5 130 ~ 205 5 Mikuni Large Hex 18-9202 Pk/5 210 ~ 370 10 MIKUNI BS30/96 TYPE PILOT JETS CV Carbs. Sold pk/5.. MIKUNI 4/042 TYPE LARGE HEX MAIN JETS 18-4818 #30 18-4824 #45 HARD PARTS NOTE: K&L jets are sold pk/5, O.E.M. Sold each 18-4819 #32.5 18-4826 #47.5 18-4820 #35 18-4828 #50 K&L(Pk/5) SIZE 18-4821 #37.5 18-4829 #52.5 18-4412 #115 18-4822 #40 18-4830 #55 18-4413 #120 18-4415 #130 18-4823 #42.5 18-4416 #135 18-4417 #140 18-4412 18-4418 #145 MIKUNI N102/221 TYPE #150 18-4419 K&L(Pk/5) SIZE O.E.M.(ea.) SMALL ROUND MAIN JETS 18-4420 #155 18-4441 #310 18-4533 Sold pk/5. -

List of Exhibitors (As of November 4, 2011)

THE 42ND TOKYO MOTOR SHOW 2011 LIST OF EXHIBITORS (AS OF NOVEMBER 4, 2011) Passenger Cars ALPINA (Germany) MERCEDES-BENZ (Germany) AMG (Germany) MINI (U.K.) AUDI (Germany) NISSAN BMW (Germany) MITSUBISHI CITROËN (France) PEUGEOT (France) DAIHATSU PORSCHE (Germany) HONDA RANGE ROVER (U.K.) JAGUAR (U.K.) RENAULT (France) KTM (Austria) *including motorcycles SMART (Germany) LAND ROVER (U.K.) SUBARU LEXUS SUZUKI *including motorcycles LOTUS (U.K.) TOYOTA MAYBACH (Germany) VOLKSWAGEN (Germany) MAZDA Commercial Vehicles HINO MITSUBISHI-FUSO HYUNDAI (Korea) UD TRUCKS ISUZU VOLVO TRUCKS (Sweden) Motorcycles ADIVA (Italy) KYMCO(Taiwan) HONDA YAMAHA KAWASAKI Carrozzeria CAMPAGNA MOTORS (Canada) RESC D ART SMILE PARK KOWA TMSUK SUNNYSIDE GARAGE NIHON AUTOMOBILE COLLEGE TAKAYAMA CARS RADICAL SPORTSCARS (U.K.) TEAM PROMINENCE Vehicle Bodies (Indoors) KANTO AUTO WORKS TOYOTA AUTO BODY NISSAN SHATAI Vehicle Bodies (Outdoors) <JABIA Joint Exhibition> Fuji Heavy Industries Ltd. ShinMaywa Industries, Ltd. Kyokuto Kaihatsu Kogyo Co., Ltd. Sugawa Shatai Co., Ltd. Nippon Fruehauf Co., Ltd. Tadano Ltd. Nippon Trex Co., Ltd. Japan Auto-Body Industries Association Inc. Pabco Co., Ltd. Parts, Machinery and Tools Advics Co., Ltd. Kyoto Tool Co., Ltd. Ahresty Corp. Kyowa Kogyo Co., Ltd. Aisin AI Co., Ltd. MAHLE Engine Components Japan Corp. Aisin AW Co., Ltd. MAHLE Filter Systems Japan Corp. Aisin Chemical Co., Ltd. MAHLE GmbH (Germany) Aisin Seiki Co., Ltd. Maeda Metal Industries, Ltd. Aisin Takaoka Co., Ltd Matsui Universal Joint Corp. Akebono Brake Industry Co., Ltd. Midori Hokuyo Co., Ltd. Amon Industry Co., Ltd. Mikuni Corp. Anden Co., Ltd. Militec Corp. (U.S.A.) Asahi Denso Co., Ltd. Mito Tool Mfg. Co., Inc. -

Notice of Hearing in Canadian Auto Parts Price-Fixing Class Actions

NOTICE OF HEARING IN CANADIAN AUTO PARTS PRICE-FIXING CLASS ACTIONS If you bought or leased, directly or indirectly, a new or used Automotive Vehicle or certain automotive parts, since January 1995 you should read this notice carefully. It may affect your legal rights. A. WHAT IS A CLASS ACTION? A class action is a lawsuit filed by one person on behalf of a large group of people. B. WHAT ARE THESE CLASS ACTIONS ABOUT? Class actions have been started in Canada claiming that many companies participated in conspiracies to fix the prices of automotive parts sold in Canada and/or sold to manufacturers for installation in Automotive Vehicles1 sold in Canada. This notice is about proposed settlements relating to 18 automotive parts (see Part D) and a proposed distribution relating to 17 automotive parts (see Part J) (the “Relevant Parts”). A description of the Relevant Parts is included in Schedule A hereto. The class actions were started in British Columbia, Ontario and/or Quebec, but include Canadian residents in all provinces and territories. The class actions claim that the companies that sell the Relevant Parts were involved in conspiracies to illegally increase the prices of these products. These class actions ask the applicable Courts to require these companies to return any extra money they may have received due to the alleged conspiracies. C. WHO IS AFFECTED BY THE CLASS ACTIONS? These class actions were certified as class proceedings as against the Settling Defendants for the purposes of implementing the settlement agreements. You are affected by the class actions mentioned above and/or are a “member” of the settlement class of those actions if you are a person in Canada who, during the relevant class period (see Schedule A): purchased or leased, directly or indirectly, a new or used Automotive Vehicle in Canada; purchased a new or used Automotive Vehicle for import into Canada; or purchased, directly or indirectly, a Relevant Part in Canada. -

Mikuni VM Roundslides X Mikuni VM Roundslides H a U S T C H E M I C a L S I N T a K E C O N T R O L S U S P E N S I O N E N G I N E

Exhaust Chemicals Intake Control Suspension Engine Electrical Vintage Tools Watercraft 48 VM Roundslides VM Roundslides f-road vehicles where pollution laws are not in wide range of tuning components are available to A Mikuni Mikuni if you have modifications, it is necessary to follow the guidelines to insure receiving the , ype of Carburetor (Clamp-On, Spigot Mount, Flange Mount, Flat-Slide, etc.) Climate Conditions (Indicate if high altitude) T Carburetor Size (mm) WEB: WWW.SUDCO.COM WEB: WWW.SUDCO.COM E-MAIL: [email protected] 7. 6. of Fuel Used Type 2. 5. of Motorcycle Use (Street, drag, Road Race, Motocross, Enduro, etc.) Type 1. 4. Modifications on motorcycle (Explain) 3. and Cubic Centimeters) Year Application (Model, Changes and jetting modifications are for use only on racing machines or similar of proper jetting at the closest range. Most popular settings are already available. However Sudco can “Special Jet” any Mikuni Carburetor for your particular application. Below is the information you will need to provide our Carburetor so they can provide you with the correct carburetor and jetting. Technicians Specialist allow precise fuel mixture These are the most popular high performance single carburetors in the sport of motorcycling. Mikuni’s VM Series round slide single carburetors These are the most popular high performance single carburetors in the sport of motorcycling. Mikuni’s application for motocross, enduro, and trail ATV have proven themselves as the performance standard for use in any cylinder motorcycle and riding, to flat track racing and road racing on both 2-stroke and 4-stroke engines. Performance features for the VM Series Carburetors include a large selection of bore sizes for increased fuel mixture flow to match engine modifications. -

Fuel Injection Systems Second Consolidated Amended Class

2:13-cv-02203-MOB Doc # 271 Filed 03/29/17 Pg 1 of 129 Pg ID 8917 REDACTED UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN SOUTHERN DIVISION ____________________________________________ ) ) In Re: AUTOMOTIVE PARTS ) 12-md-02311 ANTITRUST LITIGATION ) Honorable Marianne O. Battani ____________________________________________ ) ) 2:13-cv-02203-MOB-MKM In re: FUEL INJECTION SYSTEMS ) ____________________________________________ ) SECOND CONSOLIDATED AMENDED ) CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT THIS RELATES TO: ) ) JURY TRIAL DEMANDED ALL END-PAYOR ACTIONS ) ) [REDACTED] ____________________________________________ ) 2:13-cv-02203-MOB Doc # 271 Filed 03/29/17 Pg 2 of 129 Pg ID 8918 REDACTED Plaintiffs Ifeoma Adams, Halley Ascher, Gregory Asken, Melissa Barron, Kimberly Bennett, David Bernstein, Ron Blau, Tenisha Burgos, Kent Busek, Jennifer Chase, Rita Cornish, Nathan Croom, Lori Curtis, Jessica Decastro, Theresia Dillard, Alena Farrell, Jane Fitzgerald, Carroll Gibbs, Dori Gilels, Jason Grala, Ian Groves, Curtis Gunnerson, Tom Halverson, Curtis Harr, Andrew Hedlund, Gary Arthur Herr, John Hollingsworth, Carol Ann Kashishian, Elizabeth Kaufman, Robert Klingler, Kelly Klosterman, James Marean, Michelle McGinn, Rebecca Lynn Morrow, Edward Muscara, Stacey Nickell, Sophie O’Keefe-Zelman, Roger Olson, William Picotte, Whitney Porter, Cindy Prince, Janne Rice, Robert Rice, Jr., Frances Gammell-Roach, Darrel Senior, Meetesh Shah, Darcy Sherman, Erica Shoaf, Arthur Stukey, Kathleen Tawney, Jane Taylor, Keith Uehara, Michael Wick, and Phillip Young (“Plaintiffs”), on behalf of themselves and all others similarly situated (the “Classes” as defined below), upon personal knowledge as to the facts pertaining to themselves and upon information and belief as to all other matters, and based on the investigation of counsel, bring this class action for damages, injunctive relief, and other relief pursuant to federal antitrust laws and state antitrust, unfair competition, consumer protection, and unjust enrichment laws, and allege as follows: NATURE OF ACTION 1. -

2021 AMA Amateur Competition Rulebook

2021 RULEBOOK 2021 AMA Racing Rules Governing Pro/Am, Standard, ATV and Youth Competition An exclusive service to members of the American Motorcyclist Association The American Motorcyclist Association takes pride in its long record of achievement as the world’s largest sanctioning body for the sport of motorcycle competition. Since 1924 the objectives of the Association have been the same: to foster strong and fair competition, to provide reasonable guidelines for the various types of competition, and to provide an impartial competition program. The rules of competition are intended only as a guide for the conduct of the sport pursuant to uniform rules. Rules related to safety are made to make everyone concerned with safety. However, the AMA neither warrants safety if the rules are followed nor compliance with the enforcement of the rules. Moreover, each participant in competition has the responsibility to assess the safety aspects of facilities and conditions and must assume the risk of competition. Recognized and non-recognized districts, and organizations within a district, must submit any temporary or locally appropriate supplemental regulations for approval by the AMA Racing Department. Supplemental regulations may not be in conflict with national rules. In the event of a protest or appeal, the judgment will be based on information contained in the AMA national rules. Contact the AMA at (800) 262-5646 for the address of your district office. The American Motorcyclist Association (AMA) prohibits discrimination in all of its programs and activities (including all AMA-sanctioned events) on the basis of race, color, national origin, creed, religion, sex, age, disability, veteran status, marital status, familial status, parental status, sexual orientation, or any other category protected by applicable state or federal law.