Planning for Missing Middle Housing in Toronto's Yellowbelt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Old East York Profile: Prevention

N58 – Old East York Profile: Prevention City of Toronto Toronto Central LHIN Old East York Indicators Count, Count, Count, ¦ (95% CI) ¦ Rate % % % ¦ ¦ Ratio* Mammograms (2009-2011) ª ¦ ¦ Women, aged 50-59 ¦ ¦ Total eligible population ** 152,883 65,948 609 ¦ ¦ % of all eligible women having a mammogram within last 2 years 54.5 53.9 58.1 ¦ (54.2-62.0) ¦ 1.07 NS Total eligible population using services *** 138,100 58,962 562 ¦ ¦ % of all women using services who also had a mammogram 60.3 60.2 63.0 ¦ (59.0-67.0) ¦ 1.04 NS Women, aged 60-69 ¦ ¦ Total eligible population ** 131,959 56,131 499 ¦ ¦ % of all eligible women having a mammogram within last 2 years 57.5 56.5 57.1 ¦ (52.8-61.5) ¦ 0.99 NS Total eligible population using services *** 121,953 51,444 468 ¦ ¦ % of all women using services who also had a mammogram 62.3 61.7 60.9 ¦ (56.5-65.3) ¦ 0.98 NS Women, aged 50-69 ¦ ¦ Total eligible population ** 284,842 122,079 1,108 ¦ ¦ % having a mammogram within last 2 years 55.9 55.1 57.7 ¦ (54.8-60.6) ¦ 1.03 NS % having a mammogram within last 2 years - Age-Adjusted † 56.1 55.3 57.6 ¦ (53.2-62.3) ¦ 1.03 NS Total eligible population using services *** 260,053 110,406 1,030 ¦ ¦ % having a mammogram within last 2 years 61.2 60.9 62.0 ¦ (59.1-65.0) ¦ 1.01 NS % having a mammogram within last 2 years - Age-Adjusted † 61.4 61.0 61.9 ¦ (57.1-66.9) ¦ 1.01 NS CI Confidence Interval. -

City of Toronto — Detached Homes Average Price by Percentage Increase: January to June 2016

City of Toronto — Detached Homes Average price by percentage increase: January to June 2016 C06 – $1,282,135 C14 – $2,018,060 1,624,017 C15 698,807 $1,649,510 972,204 869,656 754,043 630,542 672,659 1,968,769 1,821,777 781,811 816,344 3,412,579 763,874 $691,205 668,229 1,758,205 $1,698,897 812,608 *C02 $2,122,558 1,229,047 $890,879 1,149,451 1,408,198 *C01 1,085,243 1,262,133 1,116,339 $1,423,843 E06 788,941 803,251 Less than 10% 10% - 19.9% 20% & Above * 1,716,792 * 2,869,584 * 1,775,091 *W01 13.0% *C01 17.9% E01 12.9% W02 13.1% *C02 15.2% E02 20.0% W03 18.7% C03 13.6% E03 15.2% W04 19.9% C04 13.8% E04 13.5% W05 18.3% C06 26.9% E05 18.7% W06 11.1% C07 29.2% E06 8.9% W07 18.0% *C08 29.2% E07 10.4% W08 10.9% *C09 11.4% E08 7.7% W09 6.1% *C10 25.9% E09 16.2% W10 18.2% *C11 7.9% E10 20.1% C12 18.2% E11 12.4% C13 36.4% C14 26.4% C15 31.8% Compared to January to June 2015 Source: RE/MAX Hallmark, Toronto Real Estate Board Market Watch *Districts that recorded less than 100 sales were discounted to prevent the reporting of statistical anomalies R City of Toronto — Neighbourhoods by TREB District WEST W01 High Park, South Parkdale, Swansea, Roncesvalles Village W02 Bloor West Village, Baby Point, The Junction, High Park North W05 W03 Keelesdale, Eglinton West, Rockcliffe-Smythe, Weston-Pellam Park, Corso Italia W10 W04 York, Glen Park, Amesbury (Brookhaven), Pelmo Park – Humberlea, Weston, Fairbank (Briar Hill-Belgravia), Maple Leaf, Mount Dennis W05 Downsview, Humber Summit, Humbermede (Emery), Jane and Finch W09 W04 (Black Creek/Glenfield-Jane -

Low Other* Dwelling Density Availability of Destinations

21 24 116 130 2 35 36 50 49 48 27 131 22 34 37 117 129 3 25 51 52 47 46 4 132 26 38 53 118 1 5 33 40 128 135 134 23 39 45 6 29 113 28 32 105 133 31 41 42 119 126 137 7 8 30 103 127 136 115 112 108 102 43 125 100 138 140 11 10 110 109 101 99 44 9 111 107 104 56 55 139 106 124 Dwelling Availability of 91 92 97 54 120 density destinations 13 90 94 96 58 123 15 89 98 57 High - High 12 114 93 59 60 14 88 95 67 61 121 83 74 66 High - Low 87 80 79 71 68 69 62 16 75 64 122 86 84 81 78 76 65 Low - High 7372 63 85 70 Low - Low 20 17 82 77 Other* 18 19 0 2.5 5 km * Indicates DB belonged to the middle quintile of Neighbourhoods dwelling density and/or availability of destinations 1 West Humber-Clairville 25 Glenfield-Jane Heights 49 Bayview Woods-Steeles 73 Moss Park 96 Casa Loma 121 Oakridge 2 Mount Olive-Silverstone- 26 Downsview-Roding-CFB 50 Newtonbrook East 74 North St. James Town 97 Yonge-St.Clair 122 Birchcliffe-Cliffside Jamestown 27 York University Heights 51 Willowdale East 75 Church-Yonge Corridor 98 Rosedale-Moore Park 123 Cliffcrest 3 Thistletown-Beaumond Heights 28 Rustic 52 Bayview Village 76 Bay Street Corridor 99 Mount Pleasant East 124 Kennedy Park 4 Rexdale-Kipling 29 Maple Leaf 53 Henry Farm 77 Waterfront Communities- 100 Yonge-Eglinton 125 Ionview 5 Elms-Old Rexdale 30 Brookhaven-Amesbury 54 O'Connor-Parkview The Island 101 Forest Hill South 126 Dorset Park 6 Kingsview Village-The Westway 31 Yorkdale-Glen Park 55 Thorncliffe Park 78 Kensington-Chinatown 102 Forest Hill North 127 Bendale 7 Willowridge-Martingrove-Richview 32 Englemount-Lawrence -

Enabling Better Places: a Handbook for Improved Neighborhoods

A Handbook Enabling for Improved Better Places Neighborhoods By AARP Livable Communities and the Congress for the New Urbanism AARP is the nation’s largest nonprofit, nonpartisan organization dedicated to empowering people 50 or older to choose how they live as they age. With nearly 38 million members and offices in every state, the District of Websites: AARP.org and AARP.org/Livable Columbia, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, AARP strengthens Email: [email protected] communities and advocates for what matters most to families, with a focus Facebook: /AARPLivableCommunities on health security, financial stability and personal fulfillment. The AARP Twitter: @AARPLivable Livable Communities initiative’s programs include the AARP Network of Free Newsletter: AARP.org/LivableSubscribe Age-Friendly States and Communities and the annual AARP Community Challenge “quick-action” grant program. The Congress for the New Urbanism’s mission is to champion walkable urbanism. CNU provides resources, education, and technical assistance to create socially just, economically robust, environmentally resilient, and people centered places. CNU leverages New Urbanism’s unique integration of design and social principle to advance three key goals: to support complete neighborhoods, legalize walkable places, to design for a climate change. With Website: CNU.org 19 local and state chapters and headquarters in Washington, D.C., CNU works Email: [email protected] to unite the New Urbanist movement. (See page 21 to learn more.) Facebook: /NewUrbanism Twitter: @NewUrbanism Free Newsletter: Members.CNU.org/Newsletter Enabling Better Places: A Handbook for Improved Neighborhoods WRITTEN AND EDITED BY: Congress for the New Urbanism Visit AARP.org/Zoning to download or order this free publication. -

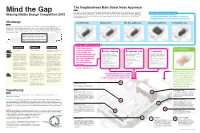

Missing Middle Design Competition 2015 Challenge Opportunity the Neighborhood Main Street Node Approach

The Neighborhood Main Street Node Approach Mind the Gap MIND THE GAP illustrates an approach to building Missing Middle housing in a Neighborhood Main Street Node within a mixed-use district in a large-sized city along a commercial corridor. The district consists of varied, mostly traditional and historic structures with heights ranging from APPROPRIATE BUILDING TYPES Missing Middle Design Competition 2015 one to four stories. This Neighborhood Main Street Node is in need of revitalization and reinvestment, including services within walking distance that provide day-to-day amenities and small local businesses. MIND THE GAP shows how medium-density housing can be appropriately In a Neighborhood Main Street Node, a number of integrated into this context. building types may be successful and well-received. Challenge Live/Work Units Stacked Units Mid-Rise Apartments Courtyard Apartments Vertical Mixed-Use Like other urban areas around the country, Michigan communities face a shortage of Missing Middle Housing. These housing options fill the void between single-family homes and high-rise apartment buildings, offering affordable medium-density residential units, typically inserted into tight sites in previously developed areas and within walkable mixed-use environments. They offer sustainable living to a broad range of people, and the market for these housing options continues to grow. Unfortunately, a number of obstacles – regulatory, financial, and perceptual – still exist to building the Missing Middle and must be addressed before these -

The Hidden Epidemic: a Report on Child and Family Poverty in Toronto

DIVIDED CITY: Life in Canada’s Child Poverty Capital 2016 Toronto Child and Family Poverty Report Card DIVIDED CITY: Life in Canada’s Child Poverty Capital 2016 Toronto Child and Family Poverty Report Card November 2016 1 DIVIDED CITY: Life in Canada’s Child Poverty Capital 2016 Toronto Child and Family Poverty Report Card Acknowledgements This report was researched and written by a working group that included: Michael Polanyi Community Development and Prevention Program, Children’s Aid Society of Toronto Jessica Mustachi Family Service Toronto (Ontario Campaign 2000) michael kerr Colour of Poverty – Colour of Change Sean Meagher Social Planning Toronto Research and data analysis support provided by the City of Toronto is gratefully acknowledged. Financial support was provided by the Children’s Aid Society of Toronto and the Children’s Aid Foundation. Design support was provided by Peter Grecco. We thank Ann Fitzpatrick, Said Dirie, Sharon Parsaud and Beth Wilson for their assistance with, and review of, the report. Data and mapping support for the transit section of the report from Steve Farber and Jeff Allen, Department of Human Geography, University of Toronto, Scarborough, is gratefully acknowledged. Data support for housing provided by Scott Leon, Wellesley Institute. 2 DIVIDED CITY: Life in Canada’s Child Poverty Capital 2016 Toronto Child and Family Poverty Report Card Contents Executive Summary 4 1. Introduction 6 2. Unequal Child and Family Incomes 8 3. Unequal Educational and Recreational Opportunities 14 4. Unequal Access to -

In-Between Issues: Exploring the “Missing Middle” in Ontario

IN-BETWEEN ISSUES: EXPLORING THE “MISSING MIDDLE” IN ONTARIO REPORT BY KAITLIN WEBBER UNIVERSITY OF WATERLOO FACULTY OF ENVIRONMENT School of Planning PRAGMA DISCUSSION PAPER |SPRING 2019 1 Photo: City of Toronto Archives (1992) ABOUT Photo: Association of Graduate Planners (2018) ABOUT WATERLOO ABOUT THE SCHOOL OF PLANNING In just half a century, the University of Waterloo, The University of Waterloo's School of Planning is the located at the heart of Canada’s technology hub, has only planning school in Canada to offer programs at become one of Canada’s leading comprehensive the bachelor's, master's, and PhD levels. Its graduates universities with 35,000 full- and part-time students in are well-qualified for the workplace - with programs undergraduate and graduate programs. A globally recognized by the Canadian Institute of Planners, and focused institution, which has been celebrated as as a co-op program, where students receive 20 Canada’s most innovative university for 26 consecutive months of paid work experience as they earn their years, Waterloo is home to the world’s largest undergraduate degrees. postsecondary cooperative education program and The School of Planning takes an interdisciplinary encourages enterprising partnership in learning, approach, with students learning about environmental research and discovery. In the next decade, the planning, urban design, political systems, law, and university is committed to building a better future for housing. Located in the Faculty of Environment's LEED Canada and the world by championing innovation and Platinum certified Environment 3 building, it draws collaboration to create solutions relevant to the needs upon multiple disciplines to research and teach issues of today and tomorrow. -

Housing Policy Toolkit 1

Sacramento Area HOUSING POLICY Council of Governments TOOLKIT Version Date: 6/25/20 A menu of policy options and best practices for removing governmental constraints to new housing at the local level in the Sacramento Region. Table of Contents Introduction and Purpose................................................................................................... 2 Purpose ............................................................................................................................................................... 2 Background ......................................................................................................................................................... 2 How to Use this Toolkit ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Zoning ............................................................................................................................. 5 Expand “Missing Middle” Zoning ......................................................................................................................... 5 Expand TOD-appropriate Zoning Near Transit ..................................................................................................... 6 Allow Housing in Commercial Zones .................................................................................................................... 7 Reduce or Remove Parking Requirements .......................................................................................................... -

Community Resources for Hip & Knee Patients

Community Resources Important: The University Health Network does not recommend one company or person over another and is not responsible for the care and services provided. Please contact the vendors directly to make sure the information is correct or to find out more about their product. This list does not claim to be exhaustive and some facilities/resources may have been inadvertently missed or not up-to-date. Equipment and Assistive Devices HOURS OF LOCATION NAME OPERATION Able Home Health Care 3537 Bathurst St. M-W 9-5 416-789-5551 (N. of Lawrence Ave. S. of Th 9-6 www.ablehomehealthcare.ca Wilson Ave.) F 9-4 Active Lite Mobility 2300 John St., Unit 3 M-F 9-5 905-764-0706 (E. of Don Mills in Thornhill) Sat 10-4 www.activelite.com AgTa Home Health Care 860 Wilson Ave., Suite 102 M-F 9-5 416-630-0737 (W. of Dufferin Ave.) www.agtahomecare.com Amcare Surgical 1584 Bathurst St. M-F 9-7 416-781-4494 (2 blocks N. of St. Clair Ave., Sat 9-5 www.amcare.ca W. side of Bathurst) Baygreen Home Health Care 8 Green Lane M-Th 9:30-6 905-771-0010 (Bayview Ave./ John St. in F 9:30-5 www.baygreen.ca Thornhill) Sat 10:30-3 Healthtime Living Specialties 1340 Danforth Ave. M, Tu, W, F 9:30- 416-693-7676 (E. of Linsmore Cres, near 5:30 www.healthtimelivingspecialties.ca Greenwood Ave.) Th 9:30-7 Sat 10-4 Home Medical Equipment 124 St. Regis Cres. -

A Study of Car and House Ownership in the Face of Increasing Commuting Expenses (CHOICE)

A Study of Car and House Ownership in the face of Increasing Commuting Expenses (CHOICE) by Elli Maria Papaioannou A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Masters of Applied Science Graduate Department of Civil Engineering University of Toronto © Copyright by Elli Maria Papaioannou, 2014 A Study of Car and House Ownership in the face of Increasing Commuting Expenses (CHOICE) Elli Maria Papaioannou Masters of Applied Science Department of Civil Engineering University of Toronto 2014 Abstract This research presents the design, implementation and results of a survey of Car and House Ownership in the face of Increasing Commuting Expenses (CHOICE). The CHOICE survey is a web-based survey that combines RP and SP components, and was designed to collect information of commuting mode choices, housing and neighbourhood preferences along with vehicle ownership choices of households with cross-regional commuters in the Greater Toronto Area. Investigations of the survey data revealed that for small increases in commuting costs people are willing to change to more efficient cars. As commuting costs reached higher levels, participants chose to relocate their home in order to commute shorter distances. This study provides evidence that vehicle ownership and especially residential location decisions are a complex process and are interrelated. The findings of this study show some of the possible reactions of households in the GTA in the face of extreme increases in transportation costs. ii Acknowledgments This two-year-long journey flew by and I am standing at the end of it today trying to think of all the challenges I faced, all the wonderful and bright people I met, all the things I learned, and all the friends I earned. -

Child & Family Inequities Score

CHILD & FAMILY INEQUITIES SCORE Technical Report The Child & Family Inequities Score provides a neighbourhood-level measure of the socio-economic challenges that children and families experience. The Child & Family Inequities Score is a tool to help explain the variation in socio-economic status across the City of Toronto neighbourhoods. It will help service providers to understand the context of the neighbourhoods and communities that they serve. It will also help policy makers and researchers understand spatial inequities in child and family outcomes. While other composite measures of socio-economic status in the City exist, the Child & Family Inequities Score is unique because it uses indicators that are specific to families with children under the age of 12. The Child & Family Inequities Score is a summary measure derived from indicators which describe inequities experienced by the child and family population in each of Toronto’s 140 neighbourhoods. The Child & Family Inequities Score is comprised of 5 indicators: • Low Income Measure: Percent of families with an after-tax family income that falls below the Low Income Measure. • Parental Unemployment: Percent of families with at least one unemployed parent / caregiver. • Low Parental Education: Percent of families with at least one parent / caregiver that does not have a high school diploma. • No Knowledge of Official Language: Percent of families with no parents who have knowledge of either official language (English or French). 1 • Core Housing Need: Percent of families in core housing need . This report provides technical details on how the Child & Family Inequities Score was created and describes how the resulting score should be interpreted. -

Every Tree Counts. a Portrait of Toronto's Urban Forest

Every Tree Counts A Portrait of Toronto’s Urban Forest Parks, Forestry & Recreation Urban Forestry Parks, Forestry & Recreation Urban Forestry Every Tree Counts A Portrait of Toronto’s Urban Forest Foreword For decades, people flying into Toronto have observed that it is a very green city. Indeed, the sight of Toronto’s tree canopy from the air is impressive. More than 20 years ago, an urban forestry colleague noted that the trees in our parks should, and in many cases do, spill over into the streets like extensions of the City’s parks. Across Toronto and the entire Greater Toronto Area, the urban forest plays a significant role in converting subdivisions into neighbourhoods. Most people have an emotional connection to trees. In cities, they represent one of our remaining links to the natural world. Properly managed urban forests provide multiple services to city residents. Cleaner air and water, cooler temperatures, energy savings and higher property values are among the many benefits. With regular man- agement, these benefits increase every year as trees continue to grow. In 2007,Toronto City Council adopted a plan to significantly expand the City’s forest cover to between 30-40%. Parks, Forestry and Recreation responded with a Forestry Service Plan aimed at managing our existing growing stock, protecting the forest and planting more trees. Strategic management requires a detailed understanding of the state of the City’s forest resource. The need for better information was a main reason to undertake this study and report on the state of Toronto’s tree canopy. Emerging technologies like the i-Tree Eco model and remote sensing techniques used in this forestry study provide managers with new tools and better information to plan and execute the expansion, protection and maintenance of Toronto’s urban forest.