Enabling Better Places: a Handbook for Improved Neighborhoods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Missing Middle Design Competition 2015 Challenge Opportunity the Neighborhood Main Street Node Approach

The Neighborhood Main Street Node Approach Mind the Gap MIND THE GAP illustrates an approach to building Missing Middle housing in a Neighborhood Main Street Node within a mixed-use district in a large-sized city along a commercial corridor. The district consists of varied, mostly traditional and historic structures with heights ranging from APPROPRIATE BUILDING TYPES Missing Middle Design Competition 2015 one to four stories. This Neighborhood Main Street Node is in need of revitalization and reinvestment, including services within walking distance that provide day-to-day amenities and small local businesses. MIND THE GAP shows how medium-density housing can be appropriately In a Neighborhood Main Street Node, a number of integrated into this context. building types may be successful and well-received. Challenge Live/Work Units Stacked Units Mid-Rise Apartments Courtyard Apartments Vertical Mixed-Use Like other urban areas around the country, Michigan communities face a shortage of Missing Middle Housing. These housing options fill the void between single-family homes and high-rise apartment buildings, offering affordable medium-density residential units, typically inserted into tight sites in previously developed areas and within walkable mixed-use environments. They offer sustainable living to a broad range of people, and the market for these housing options continues to grow. Unfortunately, a number of obstacles – regulatory, financial, and perceptual – still exist to building the Missing Middle and must be addressed before these -

Planning for Missing Middle Housing in Toronto's Yellowbelt

Filling in the Housing Gaps: Planning for Missing Middle Housing in Toronto’s Yellowbelt By Aria Popal Supervised by Dr. Luisa Sotomayor A Major Paper submitted to the Faculty of Environmental Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Environmental Studies York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada July 31st, 2020 i ABSTRACT The City of Toronto is experiencing a well-known housing affordability crisis. As the fastest growing city in North America with the highest construction activity, expensive condominium developments in the City’s designated areas for growth, such as the downtown core, are dominating the housing market as the leading type of supply. On the other hand, Toronto prides itself upon being a city of neighbourhoods, by alluding to the other form of supply in the city as single-family homes or single detached dwellings. To contend with the convolutions of the housing market, a discourse of the Missing Middle emerged in the 2010s as a new angle from which to examine the housing affordability crisis in North American cities. The Missing Middle is a multifaceted term that generally refers to a need for more housing typologies that are in scale with single-family homes but are limited to four units in height; to be added as gentle or medium density to designated single-family neighbourhoods. I assess the Missing Middle as an approach, a strategy, and a discourse to moderate the housing crisis. By conducting interviews with interested city-builders, community members and vocal advocates for the development of Missing Middle housing in Toronto, this paper presents different views and perspectives on the limits and opportunities that such approach may provide. -

In-Between Issues: Exploring the “Missing Middle” in Ontario

IN-BETWEEN ISSUES: EXPLORING THE “MISSING MIDDLE” IN ONTARIO REPORT BY KAITLIN WEBBER UNIVERSITY OF WATERLOO FACULTY OF ENVIRONMENT School of Planning PRAGMA DISCUSSION PAPER |SPRING 2019 1 Photo: City of Toronto Archives (1992) ABOUT Photo: Association of Graduate Planners (2018) ABOUT WATERLOO ABOUT THE SCHOOL OF PLANNING In just half a century, the University of Waterloo, The University of Waterloo's School of Planning is the located at the heart of Canada’s technology hub, has only planning school in Canada to offer programs at become one of Canada’s leading comprehensive the bachelor's, master's, and PhD levels. Its graduates universities with 35,000 full- and part-time students in are well-qualified for the workplace - with programs undergraduate and graduate programs. A globally recognized by the Canadian Institute of Planners, and focused institution, which has been celebrated as as a co-op program, where students receive 20 Canada’s most innovative university for 26 consecutive months of paid work experience as they earn their years, Waterloo is home to the world’s largest undergraduate degrees. postsecondary cooperative education program and The School of Planning takes an interdisciplinary encourages enterprising partnership in learning, approach, with students learning about environmental research and discovery. In the next decade, the planning, urban design, political systems, law, and university is committed to building a better future for housing. Located in the Faculty of Environment's LEED Canada and the world by championing innovation and Platinum certified Environment 3 building, it draws collaboration to create solutions relevant to the needs upon multiple disciplines to research and teach issues of today and tomorrow. -

Housing Policy Toolkit 1

Sacramento Area HOUSING POLICY Council of Governments TOOLKIT Version Date: 6/25/20 A menu of policy options and best practices for removing governmental constraints to new housing at the local level in the Sacramento Region. Table of Contents Introduction and Purpose................................................................................................... 2 Purpose ............................................................................................................................................................... 2 Background ......................................................................................................................................................... 2 How to Use this Toolkit ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Zoning ............................................................................................................................. 5 Expand “Missing Middle” Zoning ......................................................................................................................... 5 Expand TOD-appropriate Zoning Near Transit ..................................................................................................... 6 Allow Housing in Commercial Zones .................................................................................................................... 7 Reduce or Remove Parking Requirements .......................................................................................................... -

A U LI Technical Assistance Panel

Special Report The Missing Middle: Affordable Housing for Middle Income Families in the City of Austin Technical Assistance Panel | March 31-April 1, 2015 Austin, Texas A Assistance A ULI TechnicalPanel ABOUT ULI – THE URBAN LAND INSTITUTE The mission of the Urban Land Institute (ULI) is to provide leadership in the responsible use of land and in creating and sustaining thriving communities worldwide. ULI is committed to: • Bringing together leaders from across the fields of real estate and land use policy to exchange best practices and serve community needs; • Fostering collaboration within and beyond ULI’s membership through mentoring, dialogue and problem solving; • Exploring issues of urbanization, conservation, regeneration, land use, capital formation, and sustainable development; • Advancing land use policies and design practices that respect the uniqueness of both built and natural environments; • Sharing knowledge through education, applied research, publishing and electronic media; and • Sustaining a diverse global network of local practice and advisory efforts that address current and future challenges. Established in 1936, the Institute today has more than 35,000 members from 90 countries, representing the entire spectrum of the land use and development disciplines. Professionals represented include developers, builders, property owners, investors, architects, public official, planners, real estate brokers, appraisers, attorneys, engineers, financiers, academics, students and librarians. ULI relies heavily on the experience of its members. It is through member involvement and information resources that ULI has been able to set standards of excellence in development practice. The Institute has long been recognized as one of the world’s most respected and widely quoted sources of objective information on urban planning, growth, and development. -

Diversifying Housing Options with Smaller Lots and Smaller Homes Photo Courtesy of Ross Chapin of Ross Courtesy Photo June 2019

Diversifying Housing Options with Smaller Lots and Smaller Homes Photo Courtesy of Ross Chapin of Ross Courtesy Photo June 2019 PREPARED FOR: National Association of Home Builders 1201 15th Street, NW Washington, D.C. 20005 PREPARED BY: Opticos Design, Inc. 2100 Milvia Street, Suite 125 Berkeley, Calif. 94704 COVER: Danielson Grove INSIDE COVER: Boiceville Cottages Table of Contents Table of Contents List of Credits .......................................2 ⦁ Rowhouse (‘Townhouse’) .......................................32 ⦁ Courtyard .................................................................33 Executive Summary ............................5 Ordinance and Code Analysis by Jurisdiction ...35 ⦁ Accessory Dwelling Unit (ADU) Ordinances ...........35 ⦁ Small Lot Ordinances and Density Incentives .......44 CHAPTER 1: ⦁ Cottage Court Ordinances ......................................52 ⦁ Database Of Land Use And Zoning Form-Based Codes (FBCs) ......................................57 Strategies ..............................................9 Chapter Summary ..................................................10 CHAPTER 3: Case Studies ...................................... 73 Database of Ordinances and Codes .....................10 Chapter Summary ...................................................74 Ranking Regulation Approaches ..........................12 Accessory Dwelling Unit (ADU) Case Studies .....75 Approaches ...............................................................14 ⦁ Garage Conversion ADU ..........................................75 -

Increasing the Supply of the Missing Middle Housing Types in Walkable Urban Core Neighborhoods: Risk, Risk Reduction and Capital

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School March 2019 Increasing the Supply of the Missing Middle Housing Types in Walkable Urban Core Neighborhoods: Risk, Risk Reduction and Capital Shrimatee Ojah Maharaj University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Land Use Law Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Scholar Commons Citation Ojah Maharaj, Shrimatee, "Increasing the Supply of the Missing Middle Housing Types in Walkable Urban Core Neighborhoods: Risk, Risk Reduction and Capital" (2019). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/7877 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Increasing the Supply of the Missing Middle Housing Types in Walkable Urban Core Neighborhoods: Risk, Risk Reduction and Capital by Shrimatee Ojah Maharaj A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Business Administration Muma College of Business University of South Florida Co-Major Professor: Gert-Jan de Vreede, Ph.D. Co-Major Professor: Gilbert Gonzalez, D.B.A. Jennifer Cainas, D.B.A Delroy Hunter, Ph.D. Dirk Libaers, Ph.D. Date of Approval: December 7, 2018 Keywords: Missing Middle housing, diverse housing, traditional neighborhoods, housing supply, millennials, baby boomers, barriers, risk, risk reduction, capital Copyright © 2019, Shrimatee Ojah Maharaj DEDICATION I dedicate this dissertation to my late parents, two eldest brothers, two sisters, two nieces, and a niece’s husband. -

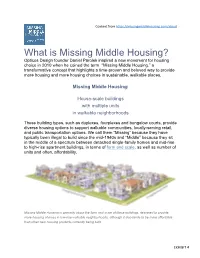

What Is Missing Middle Housing?

Content from https://missingmiddlehousing.com/about What is Missing Middle Housing? Opticos Design founder Daniel Parolek inspired a new movement for housing choice in 2010 when he coined the term “Missing Middle Housing,” a transformative concept that highlights a time-proven and beloved way to provide more housing and more housing choices in sustainable, walkable places. Missing Middle Housing: House-scale buildings with multiple units in walkable neighborhoods These building types, such as duplexes, fourplexes and bungalow courts, provide diverse housing options to support walkable communities, locally-serving retail, and public transportation options. We call them “Missing” because they have typically been illegal to build since the mid-1940s and “Middle” because they sit in the middle of a spectrum between detached single-family homes and mid-rise to high-rise apartment buildings, in terms of form and scale, as well as number of units and often, affordability. Missing Middle Housing is primarily about the form and scale of these buildings, designed to provide more housing choices in low-rise walkable neighborhoods, although it also tends to be more affordable than other new housing products currently being built. EXHIBIT 4 And while they are “missing” from our new building stock, these types of buildings from the 1920s and 30s are beloved by many who have lived in them. Ask around, and your aunt may have fond memories of living in a fourplex as a child, or you might remember visiting your grandmother as she grew old in a duplex with neighbors nearby to help her out. And today, young couples, teachers, single, professional women and baby boomers are among those looking for ways to live in a walkable neighborhood, but without the cost and maintenance burden of a detached single-family home. -

Normancentercityvision CHARRETTE SUMMARY REPORT JULY 2014 Center Cityvision Normancentercityvision WAS CREATED BY

NormanCenterCityVision CHARRETTE SUMMARY REPORT JULY 2014 Center CityVision NormanCenterCityVision WAS CREATED BY: Center CityVision and RESIDENTS OF THE CITY OF NORMAN City of Norman Staff Center City Vision Steering Committee, • Susan Connors, Planning and Community continued Development Director • Cindy Rogers • Susan Atkinson, Neighborhood Planner • Cindy Rosenthal, Project Co-Chair, Executive Committee member Center City Vision Steering Committee • Chad Williams • Jim Adair • Barrett Williamson • Rebecca Bean • Heather Woods-O’Connell • Susan Connors • Jonathan Fowler Charrette Sponsors • Judy Hatfield • Image Net Consulting • Dwight Helt • Institute for Quality Communities • Stephen Tyler Holman • Judy Hatfield • Greg Jungman • Loveworks Leadership • Richard McKown, Project Co-Chair, • NEDC Norman Economic Development Executive Committee member Council • Becky Patten • Norman Chamber of Commerce • Daniel Pullin, Executive Committee • Norman Downtowners Association member • Republic Bank & Trust • University of Oklahoma Norman Center City Vision Summary Report | ii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Project and Process .................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Background 1.2 Previous Plans and Studies 1.3 Pre-Charrette Activities, March 25-26th, 2014 1.3.1 March 25th, Committee meetings and interviews 1.3.2 March 26th, Public Kick-off Meeting 1.4 The Visioning Charrette, May 12-16th, 2014 1.4.1 May 12th, Opening Meeting 1.4.2 May 13-15th, The Charrette Design Studio -

Speaker Daniel Parolek Makes Case for “Missing Middle Housing”

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Ann Black | AARP Iowa | 515-697-1003 | [email protected] Thursday, December 1, 2016 Gunnar Olson | Des Moines Area MPO | 515-334-0075 | [email protected] Speaker Daniel Parolek makes case for “Missing Middle Housing” Aging Boomers want a different kind of housing than earlier generations – more walkable, urban environments that foster human interaction and allow easy access to nearby amenities. Architect Daniel Parolek, the next speaker in The Tomorrow Plan 2016 Speaker Series, will give a talk Dec. 16 in Des Moines on how the region can meet these demands with “Missing Middle Housing,” a range of multi-unit or clustered housing types compatible in scale with single-family homes while supporting walkable urban living. “The needs are shifting for a significant share of the region’s residents as they age,” said Kent Sovern, state director for AARP Iowa. “As a region we can choose to respond to their needs, including a broader range of housing options. We can create the kind of walkable, urban environments where the 50-plus population can live their best lives – and spend their money – engaged in the community. We see this as an incredible opportunity.” Parolek’s presentation is at 8 a.m. Friday, December 16, at the Olsen Center at Des Moines University, 3200 Grand Ave., Des Moines. His remarks are the keynote for the 2016 annual meeting of the Greater Des Moines Age Friendly Initiative report to the community. The meeting is free to attend and open to the public. Complimentary continental breakfast begins at 7:30 a.m.