Shapeshifter – Knowledge of the Moon in Graeco-Roman Egypt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ocean Data Standards

Manuals and Guides 54 Ocean Data Standards Volume 2 Recommendation to Adopt ISO 8601:2004 as the Standard for the Representation of Date and Time in Oceanographic Data Exchange UNESCO Manuals and Guides 54 Ocean Data Standards Volume 2 Recommendation to Adopt ISO 8601:2004 as the Standard for the Representation of Date and Time in Oceanographic Data Exchange UNESCO 2011 IOC Manuals and Guides, 54, Volume 2 Version 1 January 2011 For bibliographic purposes this document should be cited as follows: Paris. Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO. 2011.Ocean Data Standards, Vol.2: Recommendation to adopt ISO 8601:2004 as the standard for the representation of dates and times in oceanographic data exchange.(IOC Manuals and Guides, 54, Vol. 2.) 17 pp. (English.)(IOC/2011/MG/54-2) © UNESCO 2011 Printed in France IOC Manuals and Guides No. 54 (2) Page (i) TABLE OF CONTENTS page 1. BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................... 1 2. DATE AND TIME FOR DATA EXCHANGE ......................................................................... 1 3. INTERNATIONAL STANDARD ISO 8601:2004 .............................................................. 1 4. DATE AND TIME REPRESENTATION................................................................................ 2 4.1 Date ................................................................................................................................................. 2 4.2 Time ............................................................................................................................................... -

Islamic Calendar from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Islamic calendar From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia -at اﻟﺘﻘﻮﻳﻢ اﻟﻬﺠﺮي :The Islamic, Muslim, or Hijri calendar (Arabic taqwīm al-hijrī) is a lunar calendar consisting of 12 months in a year of 354 or 355 days. It is used (often alongside the Gregorian calendar) to date events in many Muslim countries. It is also used by Muslims to determine the proper days of Islamic holidays and rituals, such as the annual period of fasting and the proper time for the pilgrimage to Mecca. The Islamic calendar employs the Hijri era whose epoch was Islamic Calendar stamp issued at King retrospectively established as the Islamic New Year of AD 622. During Khaled airport (10 Rajab 1428 / 24 July that year, Muhammad and his followers migrated from Mecca to 2007) Yathrib (now Medina) and established the first Muslim community (ummah), an event commemorated as the Hijra. In the West, dates in this era are usually denoted AH (Latin: Anno Hegirae, "in the year of the Hijra") in parallel with the Christian (AD) and Jewish eras (AM). In Muslim countries, it is also sometimes denoted as H[1] from its Arabic form ( [In English, years prior to the Hijra are reckoned as BH ("Before the Hijra").[2 .(ﻫـ abbreviated , َﺳﻨﺔ ﻫِ ْﺠﺮﻳّﺔ The current Islamic year is 1438 AH. In the Gregorian calendar, 1438 AH runs from approximately 3 October 2016 to 21 September 2017.[3] Contents 1 Months 1.1 Length of months 2 Days of the week 3 History 3.1 Pre-Islamic calendar 3.2 Prohibiting Nasī’ 4 Year numbering 5 Astronomical considerations 6 Theological considerations 7 Astronomical -

Alexander Jones Calendrica I: New Callippic Dates

ALEXANDER JONES CALENDRICA I: NEW CALLIPPIC DATES aus: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 129 (2000) 141–158 © Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, Bonn 141 CALENDRICA I: NEW CALLIPPIC DATES 1. Introduction. Callippic dates are familiar to students of Greek chronology, even though up to the present they have been known to occur only in a single source, Ptolemy’s Almagest (c. A.D. 150).1 Ptolemy’s Callippic dates appear in the context of discussions of astronomical observations ranging from the early third century B.C. to the third quarter of the second century B.C. In the present article I will present new attestations of Callippic dates which extend the period of the known use of this system by almost two centuries, into the middle of the first century A.D. I also take the opportunity to attempt a fresh examination of what we can deduce about the Callippic calendar and its history, a topic that has lately been the subject of quite divergent treatments. The distinguishing mark of a Callippic date is the specification of the year by a numbered “period according to Callippus” and a year number within that period. Each Callippic period comprised 76 years, and year 1 of Callippic Period 1 began about midsummer of 330 B.C. It is an obvious, and very reasonable, supposition that this convention for counting years was instituted by Callippus, the fourth- century astronomer whose revisions of Eudoxus’ planetary theory are mentioned by Aristotle in Metaphysics Λ 1073b32–38, and who also is prominent among the authorities cited in astronomical weather calendars (parapegmata).2 The point of the cycles is that 76 years contain exactly four so-called Metonic cycles of 19 years. -

WLOTA LIGHTHOUSE CALENDAR by F5OGG – WLOTA Manager

WLOTA LIGHTHOUSE CALENDAR By F5OGG – WLOTA Manager Bulletin: Week 30/2021 Current and upcoming WLOTA lighthouse activations H/c = Home Call (d/B) = Direct or Bureau (d) = Direct Only (B) = Bureau Only (e) = eMail Request [C] = Special event Certificate In Yellow: WLOTA Expedition need validation In Blue: New WLOTA Expedition since last week ================================================================================== Listing is by calendar date (day/month/year) 2021 01/01-22/08 KH0/KC0W: Saipan – Island WLOTA 1333 QSL via home call, direct only - No Buro 01/01-31/12 GB1OOH: England - Main Island WLOTA 1841 QSL via M0GPN (d/B) 01/01-31/12 II9MMI: Sicilia Island WLOTA 1362 QSL IT9GHW (d/B) 01/01-31/12 GB0LMR: England - Main Island WLOTA 1841 QSL 2E1HQY (d/B) 01/01-31/12 IO9MMI: Sicilia Island WLOTA 1362 QSL via IT9MRM (d/B) 01/01-31/12 IR9MMI: Sicilia Island WLOTA 1362 QSL via IT9YBL (d/B) 01/01-31/12 GB75ISWL: England - Main Island WLOTA 1841 QSL G6XOU (d/B), eQSL.cc 01/01-31/12 8J3ZNJ: Honshu – Island WLOTA 2376 QSL JARL bureau 01/01-31/12 GB80ATC: England - Main Island WLOTA 1841 QSL via QRZ.com info 01/01-31/12 ZD8HZ: Ascension Island WLOTA 1491 QSL via TA1HZ direct, LOTW, ClubLog, HRDLog or eQSL.cc 01/01-31/12 MX1SWL/A: England - Main Island WLOTA 1841 QSL via M5DIK (d/B) 01/01-31/12 IO0MMI: Sardinia Island WLOTA 1608 QSL via IM0SDX (d/B) 01/01-31/12 GB5ST: England - Main Island WLOTA 1841 QSL via RSGB bureau 07/01-31/12 ZC4GR: Cyprus - UK Souvereign Bases Only – Island WLOTA 0892 QSL via EB7DX (see QRZ.com) 23/01-31/12 8J2SUSON: -

II. Causes of Tides III. Tidal Variations IV. Lunar Day and Frequency of Tides V

Tides I. What are Tides? II. Causes of Tides III. Tidal Variations IV. Lunar Day and Frequency of Tides V. Monitoring Tides Wikimedia FoxyOrange [CC BY-SA 3.0 Tides are not explicitly included in the NGSS PerFormance Expectations. From the NGSS Framework (M.S. Space Science): “There is a strong emphasis on a systems approach, using models oF the solar system to explain astronomical and other observations oF the cyclic patterns oF eclipses, tides, and seasons.” From the NGSS Crosscutting Concepts: Observed patterns in nature guide organization and classiFication and prompt questions about relationships and causes underlying them. For Elementary School: • Similarities and diFFerences in patterns can be used to sort, classiFy, communicate and analyze simple rates oF change For natural phenomena and designed products. • Patterns oF change can be used to make predictions • Patterns can be used as evidence to support an explanation. For Middle School: • Graphs, charts, and images can be used to identiFy patterns in data. • Patterns can be used to identiFy cause-and-eFFect relationships. The topic oF tides have an important connection to global change since spring tides and king tides are causing coastal Flooding as sea level has been rising. I. What are Tides? Tides are one oF the most reliable phenomena on Earth - they occur on a regular and predictable cycle. Along with death and taxes, tides are a certainty oF liFe. Tides are apparent changes in local sea level that are the result of long-period waves that move through the oceans. Photos oF low and high tide on the coast oF the Bay oF Fundy in Canada. -

Building Structures on the Moon and Mars: Engineering Challenges and Structural Design Parameters for Proposed Habitats

Building Structures on the Moon and Mars: Engineering Challenges and Structural Design Parameters for Proposed Habitats Ramesh B. Malla, Ph.D., F. ASCE, A.F. AIAA Professor Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT 06269 (E-Mail: [email protected]) Presented at the Breakout Panel Session- Theme C - Habitats (Preparation and Architecture) RETH Workshop- Grand Challenges and Key Research Questions to Achieve Resilient Long-Term Extraterrestrial Habitats Purdue University; October 22-23, 2018 What is Structural Resiliency? Characterized by four traits: Robustness Ability to maintain critical functions in crisis Minimization of direct and indirect Resourcefulness losses from hazards through enhanced Ability to effectively manage crisis as it resistance and robustness to extreme unfolds events, as well as more effective Rapid Recovery recovery strategies. Reconstitute normal operations quickly and effectively Redundancy Backup resources to support originals Per: National Infrastructure Advisory Council, 2009 Hazard Sources & Potential Lunar Habitats Potential Hazard Sources Available Habitat Types Impact (Micrometeorite, Debris) Inflatable Hard Vacuum Membrane Extreme Temperature Rigid-Frame Structure Seismic Activity Hybrid Frame- Low Gravity “Bessel Crater” - https://www.lpi.usra.edu/science/kiefer/Education/SSRG2- Craters/craterstructure.html Membrane Radiation Structure Galactic Cosmic Rays (GCR) Subsurface Solar-Emitted Particles (SEP) Variants Malla, et al. (1995) -

Png Medical Manual Volume 5 Part E

Civil Aviation Safety Authority Of Papua New Guinea PNG MEDICAL MANUAL VOLUME 5 PART E Control Copy Number: …………… PNG MEDICAL MANUAL PRELIMINARY AUTHORISATION Page III of XIII AUTHORIZATION This manual is a Civil Aviation Safety Authority document setting out the procedures for aviation medical practices and forms part of the Civil Aviation Safety Authority Manual Suite. This manual sets out responsibilities; specific procedures and systems applicable to Aviation Medical Standards and Certification. The main purpose of the PNG Medical Manual is to assist and guide designated aviation medical examiners (DAMEs), medical assessors (MAs) and CASA, in decisions relating to the medical fitness of licence applicants as specified in Annex 1. The originator or Controlling Authority of this document is the Principal Medical Officer (PMO). For the purpose of ensuring that the process detailed in this document is standardised, I require all designated aviation medical examiners and relevant staff to use this document in the performance of their duties. This manual is a living document and I encourage DAMEs, Mas and CASA staff to continually contribute to its improvement taking into account the legislative changes, annex amendments and latest technological changes and experience, and also to your work practices covered by the procedures contained in this document. This document has been issued under the authority of the Director of the Civil Aviation Safety Authority. Rev. No. 01 Civil Aviation Safety Authority of Papua New Guinea Revision Date: 30/11/2017 PNG MEDICAL MANUAL PRELIMINARY AUTHORISATION Page IV of XIII INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Rev. No. 01 Civil Aviation Safety Authority of Papua New Guinea Revision Date: 30/11/2017 PNG MEDICAL MANUAL PRELIMINARY CONDITION OF USE Page V of XIII CONDITION OF USE The assigned manual holder is responsible for the care and upkeep of the manual, and for its revision, in accordance with any instructions or revision material provided by the Civil Aviation Safety Authority. -

The Calendars of India

The Calendars of India By Vinod K. Mishra, Ph.D. 1 Preface. 4 1. Introduction 5 2. Basic Astronomy behind the Calendars 8 2.1 Different Kinds of Days 8 2.2 Different Kinds of Months 9 2.2.1 Synodic Month 9 2.2.2 Sidereal Month 11 2.2.3 Anomalistic Month 12 2.2.4 Draconic Month 13 2.2.5 Tropical Month 15 2.2.6 Other Lunar Periodicities 15 2.3 Different Kinds of Years 16 2.3.1 Lunar Year 17 2.3.2 Tropical Year 18 2.3.3 Siderial Year 19 2.3.4 Anomalistic Year 19 2.4 Precession of Equinoxes 19 2.5 Nutation 21 2.6 Planetary Motions 22 3. Types of Calendars 22 3.1 Lunar Calendar: Structure 23 3.2 Lunar Calendar: Example 24 3.3 Solar Calendar: Structure 26 3.4 Solar Calendar: Examples 27 3.4.1 Julian Calendar 27 3.4.2 Gregorian Calendar 28 3.4.3 Pre-Islamic Egyptian Calendar 30 3.4.4 Iranian Calendar 31 3.5 Lunisolar calendars: Structure 32 3.5.1 Method of Cycles 32 3.5.2 Improvements over Metonic Cycle 34 3.5.3 A Mathematical Model for Intercalation 34 3.5.3 Intercalation in India 35 3.6 Lunisolar Calendars: Examples 36 3.6.1 Chinese Lunisolar Year 36 3.6.2 Pre-Christian Greek Lunisolar Year 37 3.6.3 Jewish Lunisolar Year 38 3.7 Non-Astronomical Calendars 38 4. Indian Calendars 42 4.1 Traditional (Siderial Solar) 42 4.2 National Reformed (Tropical Solar) 49 4.3 The Nānakshāhī Calendar (Tropical Solar) 51 4.5 Traditional Lunisolar Year 52 4.5 Traditional Lunisolar Year (vaisnava) 58 5. -

WLOTA LIGHTHOUSE CALENDAR by F5OGG – WLOTA Manager

WLOTA LIGHTHOUSE CALENDAR By F5OGG – WLOTA Manager Bulletin: Week 23/2021 Current and upcoming WLOTA lighthouse activations H/c = Home Call (d/B) = Direct or Bureau (d) = Direct Only (B) = Bureau Only (e) = eMail Request [C] = Special event Certificate In Yellow: WLOTA Expedition need validation In Blue: New WLOTA Expedition since last week ================================================================================== Listing is by calendar date (day/month/year) 2021 01/01-06/06 KH0/KC0W: Saipan – Island WLOTA 1333 QSL via home call, direct only - No Buro 01/01-13/06 KG4MA: Guantanamo WLOTA 0358 QSL TBD 01/01-31/07 8J1TANA: Honshu – Island WLOTA 2376 QSL via the JARL bureau 01/01-06/08 8N2OBU: Honshu – Island WLOTA 2376 QSL via JARL Buro 01/01-31/12 GB1OOH: England - Main Island WLOTA 1841 QSL via M0GPN (d/B) 01/01-31/12 II9MMI: Sicilia Island WLOTA 1362 QSL IT9GHW (d/B) 01/01-31/12 GB0LMR: England - Main Island WLOTA 1841 QSL 2E1HQY (d/B) 01/01-31/12 IO9MMI: Sicilia Island WLOTA 1362 QSL via IT9MRM (d/B) 01/01-31/12 IR9MMI: Sicilia Island WLOTA 1362 QSL via IT9YBL (d/B) 01/01-31/12 GB75ISWL: England - Main Island WLOTA 1841 QSL G6XOU (d/B), eQSL.cc 01/01-31/12 8J3ZNJ: Honshu – Island WLOTA 2376 QSL JARL bureau 01/01-31/12 GB80ATC: England - Main Island WLOTA 1841 QSL via QRZ.com info 01/01-31/12 ZD8HZ: Ascension Island WLOTA 1491 QSL via TA1HZ direct, LOTW, ClubLog, HRDLog or eQSL.cc 01/01-31/12 MX1SWL/A: England - Main Island WLOTA 1841 QSL via M5DIK (d/B) 01/01-31/12 IO0MMI: Sardinia Island WLOTA 1608 QSL via IM0SDX (d/B) 01/01-31/12 -

Multi-Lunar Day Polar Missions with a Solar-Only Rover. A. Colaprete1, R

Survive the Lunar Night Workshop 2018 (LPI Contrib. No. 2106) 7007.pdf Multi-Lunar Day Polar Missions with a Solar-Only Rover. A. Colaprete1, R. C. Elphic1, M. Shirley1, M. Siegler2, 1NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA, 2Planetary Science Institute, Tucson, AZ Introduction: Resource Prospector (RP) was a lu- Polar Solar “Oases”: Numerous studies have nar HEOMD/Advanced Exploration Systems volatiles identified regions near the lunar poles that have sus- prospecting mission developed for potential flight in tained periods of solar illumination. In some places the early 2020s. The mission includes a rover-borne these periods of sustained sunlight extend across sever- payload that (1) can locate surface and near-subsurface al lunations, while others have very short (24-48 hours) volatiles, (2) excavate and analyze samples of the vola- nights. A study was conducted to evaluate if the RP tile-bearing regolith, and (3) demonstrate the form, rover system could take advantage of these “oases” to extractability and usefulness of the materials. The pri- survive the lunar night. While the Earth would set, as mary mission goal for RP is to evaluate the In-Situ seen by the rover, every approximately 2-weeks, these Resource Utilization (ISRU) potential of the lunar “oases” could provide sufficient power, and have lu- poles, to determine their utility within future NASA nar-nights short enough, for the rover system to sur- and commercial spaceflight architectures. While the vive. current RP rover design did not require a system that Results: The study focused in the area surrounding could survive lunar nights, it has been demonstrated the north pole crater Hermite-A (primarily due to the that the current design could conduct multi-lunar day fidelity of existing traverse planner data sets in this missions by taking advantage of areas that receive pro- area). -

Feasts and Festivals Around the World Culturally Significant Events

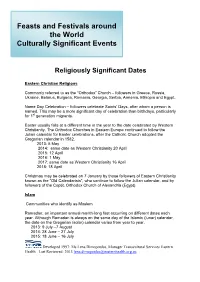

Feasts and Festivals around the World Culturally Significant Events Religiously Significant Dates Eastern Christian Religions Commonly referred to as the “Orthodox” Church – followers in Greece, Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Bulgaria, Romania, Georgia, Serbia, Armenia, Ethiopia and Egypt. Name Day Celebration – followers celebrate Saints’ Days, after whom a person is named. This may be a more significant day of celebration than birthdays, particularly for 1st generation migrants. Easter usually falls at a different time in the year to the date celebrated by Western Christianity. The Orthodox Churches in Eastern Europe continued to follow the Julian calendar for Easter celebrations, after the Catholic Church adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1582. 2013: 5 May 2014: same date as Western Christianity 20 April 2015: 12 April 2016: 1 May 2017: same date as Western Christianity 16 April 2018: 18 April Christmas may be celebrated on 7 January by those followers of Eastern Christianity known as the “Old Calendarists”, who continue to follow the Julian calendar, and by followers of the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria (Egypt). Islam Communities who identify as Moslem Ramadan: an important annual month-long fast occurring on different dates each year. Although Ramadan is always on the same day of the Islamic (lunar) calendar, the date on the Gregorian (solar) calendar varies from year to year. 2013: 9 July –7 August 2014: 28 June – 27 July 2015: 18 June – 16 July Developed 1997: Ms Lena Dimopoulos, Manager Transcultural Services Eastern Health Last Reviewed: 2013 [email protected] 2016: 6 June – 5 July 2017: 27 May – 25 July 2018: 16 May – 14 June New Year: some Moslems may fast during daylight hours. -

Lunar Sourcebook : a User's Guide to the Moon

3 THE LUNAR ENVIRONMENT David Vaniman, Robert Reedy, Grant Heiken, Gary Olhoeft, and Wendell Mendell 3.1. EARTH AND MOON COMPARED fluctuations, low gravity, and the virtual absence of any atmosphere. Other environmental factors are not The differences between the Earth and Moon so evident. Of these the most important is ionizing appear clearly in comparisons of their physical radiation, and much of this chapter is devoted to the characteristics (Table 3.1). The Moon is indeed an details of solar and cosmic radiation that constantly alien environment. While these differences may bombard the Moon. Of lesser importance, but appear to be of only academic interest, as a measure necessary to evaluate, are the hazards from of the Moon’s “abnormality,” it is important to keep in micrometeoroid bombardment, the nuisance of mind that some of the differences also provide unique electrostatically charged lunar dust, and alien lighting opportunities for using the lunar environment and its conditions without familiar visual clues. To introduce resources in future space exploration. these problems, it is appropriate to begin with a Despite these differences, there are strong bonds human viewpoint—the Apollo astronauts’ impressions between the Earth and Moon. Tidal resonance of environmental factors that govern the sensations of between Earth and Moon locks the Moon’s rotation working on the Moon. with one face (the “nearside”) always toward Earth, the other (the “farside”) always hidden from Earth. 3.2. THE ASTRONAUT EXPERIENCE The lunar farside is therefore totally shielded from the Earth’s electromagnetic noise and is—electro- Working within a self-contained spacesuit is a magnetically at least—probably the quietest location requirement for both survival and personal mobility in our part of the solar system.