The Many Editions of the Front Page: How Gender Shapes the Story

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Front Page First Opened at the Times Square Theatre on August 14, 1928, It Was Instantly Heralded As a Classic

SUPPORT FOR THE 2019 SEASON OF THE FESTIVAL THEATRE IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY DANIEL BERNSTEIN AND CLAIRE FOERSTER PRODUCTION SUPPORT IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY NONA MACDONALD HEASLIP 2 DIRECTOR’S NOTES SCAVENGING FOR THE TRUTH BY GRAHAM ABBEY “Were it left to me to decide between a government without newspapers or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.” – Thomas Jefferson, 1787 When The Front Page first opened at the Times Square Theatre on August 14, 1928, it was instantly heralded as a classic. Nearly a century later, this iconic play has retained its place as one of the great American stage comedies of all time. Its lasting legacy stands as a testament to its unique DNA: part farce, part melodrama, with a healthy dose of romance thrown into the mix, The Front Page is at once a veneration and a reproof of the gritty, seductive world of Chicago journalism, firmly embedded in the freewheeling euphoria of the Roaring Twenties. According to playwrights (and former Chicago reporters) Charles MacArthur and Ben Hecht, the play allegedly found its genesis in two real-life events: a practical joke carried out on MacArthur as he was heading west on a train with his fiancée, and the escape and disappearance of the notorious gangster “Terrible” Tommy consuming the conflicted heart of a city O’Conner four days before his scheduled caught in the momentum of progress while execution at the Cook County Jail. celebrating the underdogs who were lost in its wake. O’Conner’s escape proved to be a seminal moment in the history of a city struggling Chicago’s metamorphosis through the to find its identity amidst the social, cultural “twisted twenties” is a paradox in and of and industrial renaissance of the 1920s. -

The Hunger Games: an Indictment of Reality Television

The Hunger Games: An Indictment of Reality Television An ELA Performance Task The Hunger Games and Reality Television Introductory Classroom Activity (30 minutes) Have students sit in small groups of about 4-5 people. Each group should have someone to record their discussion and someone who will report out orally for the group. Present on a projector the video clip drawing comparisons between The Hunger Games and shows currently on Reality TV: (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wdmOwt77D2g) After watching the video clip, ask each group recorder to create two columns on a piece of paper. In one column, the group will list recent or current reality television shows that have similarities to the way reality television is portrayed in The Hunger Games. In the second column, list or explain some of those similarities. To clarify this assignment, ask the following two questions: 1. What are the rules that have been set up for The Hunger Games, particularly those that are intended to appeal to the television audience? 2. Are there any shows currently or recently on television that use similar rules or elements to draw a larger audience? Allow about 5 to 10 minutes for students to work in their small groups to complete their lists. Have students report out on their group work, starting with question #1. Repeat the report out process with question #2. Discuss as a large group the following questions: 1. The narrator in the video clip suggests that entertainments like The Hunger Games “desensitize us” to violence. How true do you think this is? 2. -

December 2010/January 2011

www.elpasobar.com December 2010/January 2011 ¡VivaEl Paso Lawyers Los and theLicenciados! Mexican Revolution-Part II By Ballard Shapleigh. Page 16 Law West Senior Lawyer Interview Byof Landon the Schmidt. Pecos Page 7 BillBy ClintonThurmond Cross. Page 11 Dec 2010 / Jan 2011 W. Reed Leverton, P.C. Attorney at Law • Mediator • Arbitrator Alternative Dispute Resolution Services 300 EAST MAIN , SUIT E 1240 EL PASO , TE XAS 79901 (915) 533-2377 - FAX: 533-2376 on-line calendar at: www.reedleverton.com Experience: Licensed Texas Attorney; Former District Judge; Over 900 Mediations Commitment to A.D.R. Processes: Full-Time Mediator / Arbitrator Commitment to Professionalism: LL.M. in Dispute Resolution Your mediation referrals are always appreciated. A mediator without borders. HARDIE MEDIATION.CO M See our website calendar and booking system Bill Hardie Mediator/Arbitrator Dec 2010 / Jan 2011 3 THE PRESIDENT’S PAGE State Bar of Texas Award of Merit The Year of the Storytellers 1996 – 1997 – 1998 – 1999 2000 – 2001 – 2006-2010 “If history were taught in the form of stories, Star of Achievement 2000 - 2008 - 2010 it would never be forgotten.” State Bar of Texas RUDYA R D KI P LING Best Overall Newsletter – 2003, 2007, 2010 Publication Achievement Award 2003 – 2005 – 2006 – 2007 – 2008 - 2010 s another calendar year comes to a close, now is a good time to reflect NABE – LexisNexis Community & Educational Outreach Award 2007 - 2010 and celebrate what has happened in our personal and professional lives. The past may be different depending on who is remembering Chantel Crews, President Bruce Koehler, President-Elect it. -

Grand Masters of Illusion

GRAND MASTERS OF ILLUSION Written and Directed by Ted & Marion Outerbridge Choreography Pattie Obey, Don Jordan Lighting Design Brad Trenaman Sound Design Ethan Rising Costume Design Peter de Castell, Marion Outerbridge Illusion Design Illusions Unlimited Artistic Consultant Lorna Wayne Haze Effects MDG Poster Design Melinda Tymm Photography Dermot Cleary Publicist Stuart McAllister Management Cameron Smillie, Live at the Hippo Pool Events PRESS KIT 2012 - 2013 SHOW OVERVIEW CLOCKWORK MYSTERIES Written and Directed by Ted and Marion Outerbridge A professionally orchestrated theatrical production with over twenty custom-designed illusions and world-class lighting and set design, OUTERBRIDGE – Clockwork Mysteries is a high-energy magical adventure for both adult and family audiences. Recognized as one of the most creative and dynamic shows of its kind, critics have hailed Ted and Marion Outerbridge as “the most successful magicians in Canada” (Montreal Gazette) and “champions of magic” (Bergedorfer Zeitung, Hamburg, Germany). As the largest and most successful touring illusion show in the country, it has received both the 2011 Award of Excellence from Ontario Contact and the 2010 Touring Artist of the Year award from the B.C. Touring Council. OUTERBRIDGE – Clockwork Mysteries takes its audience on a bizarre and fascinating journey through time. Within seconds of taking the stage, the Outerbridges fuse their revolutionary illusions with split-second artistry to hold viewers spellbound. With the help of an elaborate Victorian time machine, the performers and spectators travel back in time together. The audience is invited into a mysterious clock tower equipped with a variety of timekeeping devices. They become part of a race against time, experience time accelerating and slowing down, and participate in predicting the contents of a time capsule. -

Screwball Syll

Webster University FLST 3160: Topics in Film Studies: Screwball Comedy Instructor: Dr. Diane Carson, Ph.D. Email: [email protected] COURSE DESCRIPTION: This course focuses on classic screwball comedies from the 1930s and 40s. Films studied include It Happened One Night, Bringing Up Baby, The Awful Truth, and The Lady Eve. Thematic as well as technical elements will be analyzed. Actors include Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant, Clark Gable, and Barbara Stanwyck. Class involves lectures, discussions, written analysis, and in-class screenings. COURSE OBJECTIVES: The purpose of this course is to analyze and inform students about the screwball comedy genre. By the end of the semester, students should have: 1. An understanding of the basic elements of screwball comedies including important elements expressed cinematically in illustrative selections from noteworthy screwball comedy directors. 2. An ability to analyze music and sound, editing (montage), performance, camera movement and angle, composition (mise-en-scene), screenwriting and directing and to understand how these technical elements contribute to the screwball comedy film under scrutiny. 3. An ability to apply various approaches to comic film analysis, including consideration of aesthetic elements, sociocultural critiques, and psychoanalytic methodology. 4. An understanding of diverse directorial styles and the effect upon the viewer. 5. An ability to analyze different kinds of screwball comedies from the earliest example in 1934 through the genre’s development into the early 40s. 6. Acquaintance with several classic screwball comedies and what makes them unique. 7. An ability to think critically about responses to the screwball comedy genre and to have insight into the films under scrutiny. -

GAILY, GAILY the NIGHT THEY RAIDED MINSKY's “In 1925, There

The one area where it succeeded perfectly was So, Rosenblum began refashioning the film, in its score by Henry Mancini. By this time, using a clever device of stock footage that Mancini was already a legend. After toiling in the would lead into the production footage, rear - GAILY, GAILY music department at Universal (the highlight of ranging and restructuring scenes, and spend - his tenure there would be Orson Welles’ Touch ing a year doing so – the result was stylish and Of Evil) , he hit it big, first with his TV score to visually interesting and it transformed the film THE NIGHT Peter Gunn – which not only provided that from disaster into a hit. THEY RAIDED MINSKY’S Blake Edwards series with its signature sound, but which also produced a best-selling album The score for Minsky’s was written by Charles on RCA – and then in a series of films for which Strouse, who’d already written several Broad - “In 1925, he provided amazing scores, one right after an - way shows, as well as the score for the film other – Breakfast At Tiffany’s, Charade, Hatari, Bonnie and Clyde . The lyrics were by Lee there was this real The Pink Panther, Days Of Wine and Roses , Adams, with whom Strouse had written the religious girl” and many others. Many of those films also pro - Broadway shows Bye Bye Birdie, All-American, duced best-selling albums. Mancini not only Golden Boy, It’s A Bird, It’s A Plane, It’s Super - knew how to score a film perfectly, but he was man and others. -

Ocean's Eleven

OCEAN'S 11 screenplay by Ted Griffin based on a screenplay by Harry Brown and Charles Lederer and a story by George Clayton Johnson & Jack Golden Russell LATE PRODUCTION DRAFT Rev. 05/31/01 (Buff) OCEAN'S 11 - Rev. 1/8/01 FADE IN: 1 EMPTY ROOM WITH SINGLE CHAIR 1 We hear a DOOR OPEN and CLOSE, followed by APPROACHING FOOTSTEPS. DANNY OCEAN, dressed in prison fatigues, ENTERS FRAME and sits. VOICE (O.S.) Good morning. DANNY Good morning. VOICE (O.S.) Please state your name for the record. DANNY Daniel Ocean. VOICE (O.S.) Thank you. Mr. Ocean, the purpose of this meeting is to determine whether, if released, you are likely to break the law again. While this was your first conviction, you have been implicated, though never charged, in over a dozen other confidence schemes and frauds. What can you tell us about this? DANNY As you say, ma'am, I was never charged. 2 INT. PAROLE BOARD HEARING ROOM - WIDER VIEW - MORNING 2 Three PAROLE BOARD MEMBERS sit opposite Danny, behind a table. BOARD MEMBER #2 Mr. Ocean, what we're trying to find out is: was there a reason you chose to commit this crime, or was there a reason why you simply got caught this time? DANNY My wife left me. I was upset. I got into a self-destructive pattern. (CONTINUED) OCEAN'S 11 - Rev. 1/8/01 2. 2 CONTINUED: 2 BOARD MEMBER #3 If released, is it likely you would fall back into a similar pattern? DANNY She already left me once. -

Nothing Sacred (United Artists Pressbook, 1937)

SEE THE BIG FIGHT! DAVID O. SELZNICK’S Sensational Technicolor Comedy NOTHING SACRED WITH CAROLE LOMBARD FREDRIC MARCH CHARLES WINNINCER WALTER CONNOLLY by the producer and director of "A Star is Born■ Directed by WILLIAM A. WELLMAN * Screen play by BEN HECHT * Released thru United Artists Coyrighted MCMXXXVII by United Artists Corporation, New York, N. Y. KNOCKOUT'- * IT'S & A KNOCKOUT TO^E^ ^&re With two great stars 1 about cAROLE {or you to talk, smg greatest comedy LOMBARD, at her top the crest ol pop- role. EREDWC MARC ^ ^ ^feer great ularity horn A s‘* ‘ cWSD.» The power oi triumph in -NOTHING SA oi yfillxanr Selznick production, h glowing beauty oi Wellman direction, combination ^ranced Technicolor {tn star ls . tS made a oi a ^ ““new 11t>en “^ ”«»•>- with selling angles- I KNOCKOUT TO SEE; » It pulls no P“che%afanXioustocount.Beveald laughs that come too to ot Carole Lomb^ mg the gorgeous, gold® the suave chmm ior the fast “JXighest powered rolejhrs oi Fredric March m the g ^ glamorous Jat star has ever had. It 9 J the scieen has great star st unusual story toeS production to th will come m on “IsOVEB:' FASHION PROMOTION ON “NOTHING SACHEH” 1AUNCHING a new type of style promotion on “The centrated in the leading style magazines and papers. And J Prisoner of Zenda,” Selznick International again local distributors of these garments will be well-equipped offers you this superior promotional effort on to go to town with you in a bang-up cooperative campaign “Nothing Sacred.” Through the agency of Lisbeth, on “Nothing Sacred.” In addition, cosmetic tie-ups are nationally famous stylist, the pick of the glamorous being made with one of the country’s leading beauticians. -

INTRODUCTION Fatal Attraction and Scarface

1 introduction Fatal Attraction and Scarface How We Think about Movies People respond to movies in different ways, and there are many reasons for this. We have all stood in the lobby of a theater and heard conflicting opin- ions from people who have just seen the same film. Some loved it, some were annoyed by it, some found it just OK. Perhaps we’ve thought, “Well, what do they know? Maybe they just didn’t get it.” So we go to the reviewers whose business it is to “get it.” But often they do not agree. One reviewer will love it, the next will tell us to save our money. What thrills one person may bore or even offend another. Disagreements and controversies, however, can reveal a great deal about the assumptions underlying these varying responses. If we explore these assumptions, we can ask questions about how sound they are. Questioning our assumptions and those of others is a good way to start think- ing about movies. We will soon see that there are many productive ways of thinking about movies and many approaches that we can use to analyze them. In Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story (1992), the actor playing Bruce Lee sits in an American movie theater (figure 1.1) and watches a scene from Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961) in which Audrey Hepburn’s glamorous character awakens her upstairs neighbor, Mr Yunioshi. Half awake, he jumps up, bangs his head on a low-hanging, “Oriental”-style lamp, and stumbles around his apart- ment crashing into things. -

1908 Journal

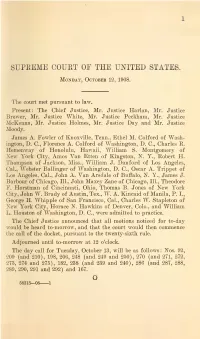

1 SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES. Monday, October 12, 1908. The court met pursuant to law. Present: The Chief Justice, Mr. Justice Harlan, Mr. Justice Brewer, Mr. Justice White, Mr. Justice Peckham, Mr. Justice McKenna, Mr. Justice Holmes, Mr. Justice Day and Mr. Justice Moody. James A. Fowler of Knoxville, Tenn., Ethel M. Colford of Wash- ington, D. C., Florence A. Colford of Washington, D. C, Charles R. Hemenway of Honolulu, Hawaii, William S. Montgomery of Xew York City, Amos Van Etten of Kingston, N. Y., Robert H. Thompson of Jackson, Miss., William J. Danford of Los Angeles, Cal., Webster Ballinger of Washington, D. C., Oscar A. Trippet of Los Angeles, Cal., John A. Van Arsdale of Buffalo, N. Y., James J. Barbour of Chicago, 111., John Maxey Zane of Chicago, 111., Theodore F. Horstman of Cincinnati, Ohio, Thomas B. Jones of New York City, John W. Brady of Austin, Tex., W. A. Kincaid of Manila, P. I., George H. Whipple of San Francisco, Cal., Charles W. Stapleton of Mew York City, Horace N. Hawkins of Denver, Colo., and William L. Houston of Washington, D. C, were admitted to practice. The Chief Justice announced that all motions noticed for to-day would be heard to-morrow, and that the court would then commence the call of the docket, pursuant to the twenty-sixth rule. Adjourned until to-morrow at 12 o'clock. The day call for Tuesday, October 13, will be as follows: Nos. 92, 209 (and 210), 198, 206, 248 (and 249 and 250), 270 (and 271, 272, 273, 274 and 275), 182, 238 (and 239 and 240), 286 (and 287, 288, 289, 290, 291 and 292) and 167. -

Mean Streets: Death and Disfiguration in Hawks's Scarface

Mean Streets: Death and Disfiguration in Hawks's Scarface ASBJØRN GRØNSTAD Consider this paradox: in Howard Hawks' Scarface, The Shame of the Nation, violence is virtually all-encompassing, yet it is a film from an era before American movies really got violent. There are no graphic close-ups of bullet wounds or slow-motion dissection of agonized faces and bodies, only a series of abrupt, almost perfunctory liquidations seemingly devoid of the heat and passion that characterize the deaths of the spastic Lyle Gotch in The Wild Bunch or the anguished Mr. Orange, slowly bleeding to death, in Reservoir Dogs. Nonetheless, as Bernie Cook correctly points out, Scarface is the most violent of all the gangster films of the eatly 1930s cycle (1999: 545).' Hawks's camera desists from examining the anatomy of the punctured flesh and the extended convulsions of corporeality in transition. The film's approach, conforming to the period style of ptc-Bonnie and Clyde depictions of violence, is understated, euphemistic, in its attention to the particulars of what Mark Ledbetter sees as "narrative scarring" (1996: x). It would not be illegitimate to describe the form of violence in Scarface as discreet, were it not for the fact that appraisals of the aesthetics of violence are primarily a question of kinds, and not degrees. In Hawks's film, as we shall see, violence orchestrates the deep structure of the narrative logic, yielding an hysterical form of plotting that hovers between the impulse toward self- effacement and the desire to advance an ethics of emasculation. Scarface is a film in which violence completely takes over the narrative, becoming both its vehicle and its determination. -

Sob Sisters: the Image of the Female Journalist in Popular Culture

SOB SISTERS: THE IMAGE OF THE FEMALE JOURNALIST IN POPULAR CULTURE By Joe Saltzman Director, Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture (IJPC) Joe Saltzman 2003 The Image of the Female Journalist in Popular Culture revolves around a dichotomy never quite resolved. The female journalist faces an ongoing dilemma: How to incorporate the masculine traits of journalism essential for success – being aggressive, self-reliant, curious, tough, ambitious, cynical, cocky, unsympathetic – while still being the woman society would like her to be – compassionate, caring, loving, maternal, sympathetic. Female reporters and editors in fiction have fought to overcome this central contradiction throughout the 20th century and are still fighting the battle today. Not much early fiction featured newswomen. Before 1880, there were few newspaperwomen and only about five novels written about them.1 Some real-life newswomen were well known – Margaret Fuller, Nelly Bly (Elizabeth Cochrane), Annie Laurie (Winifred Sweet or Winifred Black), Jennie June (Jane Cunningham Croly) – but most female journalists were not permitted to write on important topics. Front-page assignments, politics, finance and sports were not usually given to women. Top newsroom positions were for men only. Novels and short stories of Victorian America offered the prejudices of the day: Newspaper work, like most work outside the home, was for men only. Women were supposed to marry, have children and stay home. To become a journalist, women had to have a good excuse – perhaps a dead husband and starving children. Those who did write articles from home kept it to themselves. Few admitted they wrote for a living. Women who tried to have both marriage and a career flirted with disaster.2 The professional woman of the period was usually educated, single, and middle or upper class.