Vol. 35, No. 3, Summer, 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

President's Message

August 2021 Headwaters NEWSLETTER OF THE STANISLAUS FLY FISHERS President’s Message Hey, how about this lovely Valley summer weather? It’s looking like 105 today. It’s only 10:00 a.m. as I write this, and I think I’m inside for the day already. While this isn’t unusual weather for this time of year, it does pose questions about Dishing when it follows the extremely dry winter we had. A CHARTER With early season low water many of our streams that we would CLUB OF FLY normally Dish at this time of year are warming sooner than normal. If you are FISHERS on water warmer than 65 degrees, please call it a day and give the Dish a INTERNATIONAL break. Carry a thermometer and keep an eye on water temps. Fortunately we have tail water streams that Dlow cool throughput the day that are the best MEMBER OF THE bet for ishing and being responsible anglers. NORTHERN Also, while concern for the well-being of our quarry is important, CALIFORNIA don’t forget to take care of yourselves if you’re going to ish through the day COUNCIL OF FLY this summer. Wear a broad brim hat, apply sunscreen liberally, maybe use a FISHERS sun gaiter, wear long sleeve shirts and enjoy being able to leave the waders INTERNATIONAL home and wet wading. I have mentioned previously that due to the virus we have had difDiculty with meeting attendance. While fully understandable it still makes it Live Meeting tough to plan meetings. Therefore, we are going to quarterly meetings until membership and folks interested in checking out the club feel better about in- No LIVE Meetings person gatherings. -

Fishing Flies from the Transkei

Location: Enclave, East Cape Province, South Africa Republic of South Africa Government: Self-governing tribal Transvaal homeland Area: 16,910 sq. mi. Swaziland Population: 2,876,122 (1985) Capital: Umtata Orange Natal Free The World’s First Fishing Fly Stamps State Cape Province Lesotho Building a Business in South Africa In 1976, Mr. Barry Kent, his partners, and the Republic of Transkei Development Corporation built a fishing fly manufacturing Eastern Cape plant at Butterworth, Transkei, South Africa. Transkei Western Cape The company, named High Flies Ltd., was one of the most modern fishing-fly manufacturing plants in the world. Pricing, quality and clever product marketing proved to be very successful. By 1979 High Flies was employing more than 350 labor-intensive Transkeians, producing over 1,000 dozen flies each day. These flies are used mainly in fly-fishing for trout and salmon. The entire production was exported to countries where these fish are prolific: America, the British Isles, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Scandinavia, and other European countries. An idea for promoting other Transkei industries was created by depicting fishing flies on postage stamps. The outcome produced a series of five sheets for each year from 1980 through 1984. Each sheet contains five different fly patterns arranged in se-tenant format. Although the last issue of these stamps appeared in 1984, the factory closed in 1983 due to a corrupt business partner and poor management by the South African/Republic of Transkei Development Corporation bureaucrats. Mr. Kent, along with approximately 390 local workers lost their jobs. Philatelic Specifications Designer: A. H. -

I'm Here Today As the Extraterrestrial Being of This Conference—As The

\)l AJLQJLI^ . I’m here today as the extraterrestrial being of this conference—as the shaggy example of what iate a Dupuyer life-form transmogrifies into when it*s transplanted away from the character-building" of the world off Montana. As I savvy it, I*ve come wuffling down out of the dark echoing canyons of space beyond Montana to try and deal with the great cosmic question—is there literary life west of Missoula? Because it is ordained somewhere that a speech is supposed to have a title, I told Margaret Kingsland I’d be talking today about "Browning, Conrad and Other World Centers." i What I have in mind when I say "world centers" are not the cosmopolitan capitals of the planet—although any of you who know something of my past, or who have spent time up in the Two Medicine country, will have some idea of how vseemed^ uptown Browning and ^onracTjiw^to a kid on a Dupuyer sheep ranch. No, the type of "world centers" I have in mind are those centralities from which each of us looks out at life—the influences that are at the core of what we end up doing in life. My belief is that part of the gauging of where we are—where we stand now, each one^of us a personal pivot point that some larger world of existence does its orbiting around—part of that gauging of ourselves means taking a look at where we came from. In "Dancing at the Rascal Fair" my narrator's closest friend spoofs him about his interest in the "Biaetefecfr 'and --Gewi s- an&.JlLgrig~-ay»4~ v for himself and me,^ ’’Angus, you're a great one for yesterdays.” And Angus says back to him,J^ "They ’ve brought us to where we are.” _think Ij __ 9k in that same vein,"~I^ougHt to begin here by looking at 9mm exanples of Browning and Conrad as ’’world centers” to me, in the way, say, that a biographer would rummage into my early years in Montana, in search of the influences that eventually brought forth my books. -

Norman Maclean (1902 - 1990)

Introducing 2012 Montana Cowboy Hall of Fame Inductee… Norman Maclean (1902 - 1990) Norman Fitzroy Maclean was an American author and scholar noted for his books A River Runs Through It and Other Stories (1976) and Young Men and Fire (1992). Born in Clarinda, Iowa, on December 23, 1902, Maclean was the son of Clara Evelyn (née Davidson; 1873-1952) and the Reverend John Norman Maclean (1862-1941), a Presbyterian minister, who managed much of the education of the young Norman and his brother Paul Davidson (1906-1938) until 1913. His parents had migrated from Nova Scotia, Canada. After Clarinda, the family relocated to Missoula, Montana in 1909. The following years were a considerable influence on and inspiration to his writings, appearing prominently in the short story The Woods, Books, and Truant Officers (1977), and semi-autobiographical novella A River Runs Through It (1976). Too young to enlist in the military during World War I, Maclean worked in logging camps and for the United States Forest Service in what is now the Bitterroot National Forest of northwestern Montana. The novella USFS 1919: The Ranger, the Cook, and a Hole in the Sky and the story "Black Ghost" in Young Men and Fire (1992) are semi- fictionalized accounts of these experiences. Maclean attended Dartmouth College, where he served as editor-in-chief of the humor magazine the Dartmouth Jack-O- Lantern; the editor-in-chief to follow him was Theodor Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss. He received his Bachelor of Arts in 1924, and chose to remain in Hanover, New Hampshire, and serve as an instructor until 1926—a time he recalled in "This Quarter I Am Taking McKeon: A Few Remarks on the Art of Teaching." He began graduate studies in English at the University of Chicago in 1928. -

INTRODUCTION by Peter Brigg

INTRODUCTION By Peter Brigg Fly fshing, not just for trout, is a multifaceted sport that will absorb you in its reality, it will take you to places of exceptional beauty, to explore, places to revel in the solitude and endless stimulation. He stands alone in the stream, a silver thread, alive, tumbling and Fly fshing, not just for trout, is a multifaceted sport that will absorb sliding in the soft morning light: around him the sights, sounds you in its reality, it will take you to places of exceptional beauty, to and smells of wilderness. Rod under his arm he carefully picks out explore, places to revel in the solitude and endless stimulation. Or, you a fy from amongst the neat rows, slides the fy box back into its vest can lose yourself between the pages of the vast literature on all facets pocket and ties on the small dry fy. Slowly, with poetic artistry he lifts of fy fshing, get absorbed by the history, the heritage, traditions and the rod and ficks the line out, gently landing the fy upstream of the skills, be transported in thought to wild places, or cast to imaginary diminishing circles of the feeding trout – watching, waiting with taut, fsh and gather knowledge. So often fy fshing is spoken of as an art quiet anticipation as the fy bobs and twirls on the current. form and having passed the half century of experience, I’m not averse to this view, just as I believe that fytying is inextricably linked to fy It is a scene we as fy fshers know well, a fascination and pre-occupation fshing, but is in its own right a craft, a form of artistry. -

American Fly Fisher (ISSN - ) Is Published Four Times a Year by the Museum at P.O

The America n Fly Fisher Journal of the American Museum of Fly Fishing Briefly, the Breviary William E. Andersen Robert A. Oden Jr. Foster Bam Erik R. Oken Peter Bowden Anne Hollis Perkins Jane Cooke Leigh H. Perkins Deborah Pratt Dawson Frederick S. Polhemus E. Bruce DiDonato, MD John Redpath Ronald Gard Roger Riccardi George R. Gibson III Franklin D. Schurz Jr. Gardner Grant Jr. Robert G. Scott James Heckman, MD Nicholas F. Selch Arthur Kaemmer, MD Gary J. Sherman, DPM Karen Kaplan Warren Stern Woods King III Ronald B. Stuckey William P. Leary III Tyler S. Thompson James Lepage Richard G. Tisch Anthony J. Magardino David H. Walsh Christopher P. Mahan Andrew Ward Walter T. Matia Thomas Weber William McMaster, MD James C. Woods Bradford Mills Nancy W. Zakon David Nichols Martin Zimmerman h c o H James Hardman David B. Ledlie - r o h William Herrick Leon L. Martuch c A y Paul Schullery h t o m i T Jonathan Reilly of Maggs Bros. and editor Kathleen Achor with the Haslinger Breviary in October . Karen Kaplan Andrew Ward President Vice President M , I received an e-mail from (page ), Hoffmann places the breviary’s Richard Hoffmann, a medieval scholar fishing notes in historical context. Gary J. Sherman, DPM James C. Woods Lwho has made multiple contribu - In October, with this issue already in Vice President Secretary tions to this journal, both as author and production, I made a long overdue trip to George R. Gibson III translator. He had been asked to assess a London. Before leaving, I contacted Treasurer text in a mid-fifteenth-century codex—a Jonathan Reilly of Maggs Bros. -

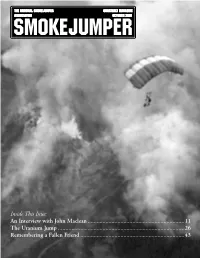

Inside This Issue: an Interview with John Maclean

The National Smokejumper Quarterly Magazine SmokejumperAssociation October 2001 Inside This Issue: An Interview with John Maclean .................................................................11 The Uranium Jump .....................................................................................26 Remembering a Fallen Friend ......................................................................43 Check the NSA Web site 1 www.smokejumpers.com CONTENTS Observations from the Ad Shack .................. 2 Observations Election Results ........................................... 2 My Brush with History/CPS 103 Jumpers ..... 3 NSA Members—Save This Information ........ 3 from the Ad Shack My Highest Jump and the Hospitality of the Silver Tip Ranch ........................ 5 Sounding Off from the Editor ....................... 8 Smokejumper magazine. A Commitment to Art Jukkala ...................... 9 At our June board meeting, “Army Brat” Commands Active Legion Post .................................................. 10 Fred Rohrbach and others An Interview with John Maclean, author suggested that the NSA should of Fire on the Mountain .................. 11 Down Side ................................................. 13 not wait five years to host The Night Pierce Burned ............................ 17 another reunion. None of us are Idaho City Jumps the Fires of Hell ............. 18 Is There Life After Smokejumping? ............ 19 getting any younger and, besides, Lois Stover ... Memories ............................ 20 we all seem to -

Halford's Dry Fly Fishing in PDF Format

kr~ ^-^ DRY-FLY FISHING. D. Moul, de. FRONTISPIECE. THE HALFORD DRY-FLY SERIES VOLUME I. DRY-FLY FISHING IN THEORY AND PRACTICE FREDERIC M. HALFORD ("DETACHED BADGER " OF " THE FIELD") author of '' " floating flies and how to dress them "making a fishery" AND " DRY-FLY ENTOMOLOGY " IN MEMORIAM George Selwyn Marryat FOURTH EDITION REVISED LONDON VINTON & CO. LIMITED 9 New Bridge Street, Ludgate Circus, E.C. 1902 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED DEDICATION OF FIRST EDITION. TO GEORGE SELWYN MARRYAT. In the last chapter of "Floating Flies and How to Dress Them," entitled " Hints to Dry-Fly Fishermen" the produc- tion of this ivork is foreshadowed. If these pages meet with the approval of our brother anglers ; if they contain anything that is likely to be useful, anything that is new, anything that is instructive, or anything that is to make dry-fly fishing a more charming or more engrossing pursuit than it now is, the novelty, the instruction, and the charm are due to the innumerable hints you have been good enough to convey to me at different times during the many days of many years ivhich we have spent together on the hanks of the Test. As a faint acknowledgment of all these obligations, and as a mark of high esteem and deep affection, this humble effort to perpetuate your teachings is dedicated to yon by Your grateful Pupil, FREDERIC M. HALFORD. November, 1888. PREFACE TO THE THIRD (REVISED) EDITION. In Memoriam George Selwyn Marryat. On the 14th of February, 1896, George Selwyn Marryat died at The Close, SaHsbury, aged 56. -

The Film Adaptation of a River Runs Through It

I SILENCE, PRIDE AND GRACE: THE FILM ADAPTATION OF A RIVER RUNS THROUGH IT by JILL L. TALBOT, B.S.Ed. A THESIS IN ENGLISH Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved May, 1995 m •X fQo .' IJ ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the members of my thesis committee. Dr. Michael Schoenecke and Dr. Wendell Aycock, for their time and expertise in helping to prepare this paper. I would like to give special thanks to Dr. Schoenecke, who introduced me to the study of film adaptation, for his continuing advice, encouragement, and friendship. Finally, thanks to David Edwards, for his constant and faithful support of my academic pursuits. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. A RIVER REMEMBERED 4 The Novella 4 Fly Fishing 8 Themes of the Novella 10 Silence 12 Pride 15 Grace 18 Love Does Not Depend on Understanding 19 A Prose of Praise 22 III. REDFORD'S ATTACHMENT AND ADAPTATION 27 Cinematic Adaptation 27 Themes of the Movie 39 The Character of Paul 45 Separation, Tradition, and Relationships ... 50 IV. CONCLUSION 55 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY 58 111 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Though nothing can bring back the hour Of splendour in the grass, of glory in the flower; We will grieve not, rather find Strength in what remains behind; --Wordsworth from Prelude In the opening lines of A River Runs Through It. Norman Maclean introduces the two most influential elements of his past: fly fishing and religion. -

Hot Water, Dry Streams: a Tale of Two Trout

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All In-stream Flows Material In-stream Flows 2010 Hot Water, Dry Streams: A Tale of Two Trout Jack R. Tuholske Vermont Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/instream_all Part of the Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Tuholske, Jack R., "Hot Water, Dry Streams: A Tale of Two Trout" (2010). All In-stream Flows Material. Paper 8. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/instream_all/8 This Publication is brought to you for free and open access by the In-stream Flows at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All In-stream Flows Material by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOT WATER, DRY STREAMS: A TALE OF TWO TROUT Jack R. Tuholske ∗† INTRODUCTION Norman Maclean’s timeless memoir A River Runs Through It begins with the reflection that in his household “there was no clear line between religion and fly fishing.” 1 That zeal remains today; nearly 30 million Americans call themselves fishermen. 2 Anglers devoted an aggregate of 517 million user-days pursuing their passion in 2006 and spent billions of dollars to support it. 3 Fishing in the western United States holds a special place in fishing lore the world over and for good reason. From the great trout waters of Montana, to the salmon-laden rivers of the west coast, to the sparkling wilderness of the Colorado Rockies, fishing in the American West is special. Many native trout and salmon in the West are also on the verge of collapse. -

The Grace of Art in a River Runs Through It

There, in the Shadows: The Grace of Art in A River Runs Through It “Any man - any artist, as Nietzsche or Cezanne would say - climbs the stairway in the tower of his perfection at the cost of a struggle with a duende - not with an angel, as some have maintained, or with his muse. This fundamental distinction must be kept in mind if the root of a work of art is to be grasped.” Frederico Garcia Lorca Don Michael Hudson King College One more summer is closing quickly, and one more summer I have not made my annual pilgrimage to Montana. I live in the south again, happily this time, and it is well-nigh September, and even though the days are hot and muggy these very same days betray certain changes to come. The air is a bit drier, almost crisp; the bitter black walnuts are thumping the ground like some mad god thumping the earth; the days are growing shorter and darker; and yet, the leaves on some of the trees are stirring belly side up sending out silvery flickerings even as twilight sets in. Maybe that is why Montana is on my mind or, rather, why Norman Maclean is. I come back to him every August whether I make it to Montana or not. Since the summer of 1995 off and on I have been fishing a section of the Blackfoot River that I will not divulge, but suffice it to say that I am one of the luckiest men on the face of this earth if for no other reason than I discovered Maclean early on, and in so doing, I found a river and a way to bring grace and art to my life. -

Journal of the American Museum of Fly Fishing

The American Fly Fisher Journal of the American Museum of Fly Fishing WINTER 2006 VOLUME 32 NUMBER 1 A Storied Sport The Salmon, painted by T. C. Hofland, in T. C. Hofland, Esq., The British Angler’s Manual (London: H. B. Bond, 1848, 24). HE STORY OF FLY FISHING is the story of beautiful places, a Fly Fisherman: The Marvels of Wood,” Masseini profiles the story of the nice neighborhoods that trout and woodworker Giorgio Dallari, builder of pipes and wooden Tsalmon call home. It’s a materialistic story, both in the reels. Dallari’s pipes have a tiny salmon icon set in gold to con- sense of the physical tools we use to accomplish the task and nect pipe smoker with fly fisher. The idea to build wooden the types of access and accommodation money can buy. It’s a reels came to Dallari after he gave up other forms of fishing for spiritual story, as men and women search out the river, its chal- fly fishing. He has been building his reels since the mid-1980s. lenges, its rewards, and its peace. It’s the story of struggle With sumptuous photos, Masseini shares the work of Giorgio toward some things and struggle against others. It’s the story Dallari with us. This story begins on page 17. of a sport, with both its obvious outward goals and its more From the material beauty of wooden reels to the more inward, metaphoric ones. abstract beauty of the spiritual reach, we present “The Last This issue of the American Fly Fisher touches a bit on all of Religious House: A River Ran Through It” (page 14).