Halford's Dry Fly Fishing in PDF Format

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

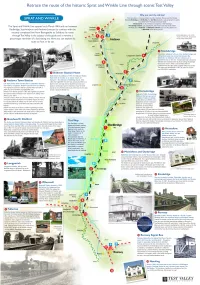

Sprat and Winkle Line Leaflet

k u . v o g . y e l l a v t s e t @ e v a e l g d t c a t n o c e s a e l P . l i c n u o C h g u o r o B y e l l a V t s e T t a t n e m p o l e v e D c i m o n o c E n i g n i k r o w n o s n i b o R e l l e h c i M y b r e h t e g o t t u p s a w l a i r e t a m e h T . n o i t a m r o f n I g n i d i v o r p r o f l l e s d n i L . D r M d n a w a h s l a W . I r M , n o t s A H . J r M , s h p a r g o t o h p g n i d i v o r p r o f y e l r e s s a C . R r M , l l e m m a G . C r M , e w o c n e l B . R r M , e n r o H . M r M , e l y o H . R r M : t e l f a e l e l k n i W d n a t a r p S e h t s d r a w o t n o i t a m r o f n i d n a s o t o h p g n i t u b i r t n o c r o f g n i w o l l o f e h t k n a h t o t e k i l d l u o w y e l l a V t s e T s t n e m e g d e l w o n k c A . -

President's Message

August 2021 Headwaters NEWSLETTER OF THE STANISLAUS FLY FISHERS President’s Message Hey, how about this lovely Valley summer weather? It’s looking like 105 today. It’s only 10:00 a.m. as I write this, and I think I’m inside for the day already. While this isn’t unusual weather for this time of year, it does pose questions about Dishing when it follows the extremely dry winter we had. A CHARTER With early season low water many of our streams that we would CLUB OF FLY normally Dish at this time of year are warming sooner than normal. If you are FISHERS on water warmer than 65 degrees, please call it a day and give the Dish a INTERNATIONAL break. Carry a thermometer and keep an eye on water temps. Fortunately we have tail water streams that Dlow cool throughput the day that are the best MEMBER OF THE bet for ishing and being responsible anglers. NORTHERN Also, while concern for the well-being of our quarry is important, CALIFORNIA don’t forget to take care of yourselves if you’re going to ish through the day COUNCIL OF FLY this summer. Wear a broad brim hat, apply sunscreen liberally, maybe use a FISHERS sun gaiter, wear long sleeve shirts and enjoy being able to leave the waders INTERNATIONAL home and wet wading. I have mentioned previously that due to the virus we have had difDiculty with meeting attendance. While fully understandable it still makes it Live Meeting tough to plan meetings. Therefore, we are going to quarterly meetings until membership and folks interested in checking out the club feel better about in- No LIVE Meetings person gatherings. -

Fishing Flies from the Transkei

Location: Enclave, East Cape Province, South Africa Republic of South Africa Government: Self-governing tribal Transvaal homeland Area: 16,910 sq. mi. Swaziland Population: 2,876,122 (1985) Capital: Umtata Orange Natal Free The World’s First Fishing Fly Stamps State Cape Province Lesotho Building a Business in South Africa In 1976, Mr. Barry Kent, his partners, and the Republic of Transkei Development Corporation built a fishing fly manufacturing Eastern Cape plant at Butterworth, Transkei, South Africa. Transkei Western Cape The company, named High Flies Ltd., was one of the most modern fishing-fly manufacturing plants in the world. Pricing, quality and clever product marketing proved to be very successful. By 1979 High Flies was employing more than 350 labor-intensive Transkeians, producing over 1,000 dozen flies each day. These flies are used mainly in fly-fishing for trout and salmon. The entire production was exported to countries where these fish are prolific: America, the British Isles, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Scandinavia, and other European countries. An idea for promoting other Transkei industries was created by depicting fishing flies on postage stamps. The outcome produced a series of five sheets for each year from 1980 through 1984. Each sheet contains five different fly patterns arranged in se-tenant format. Although the last issue of these stamps appeared in 1984, the factory closed in 1983 due to a corrupt business partner and poor management by the South African/Republic of Transkei Development Corporation bureaucrats. Mr. Kent, along with approximately 390 local workers lost their jobs. Philatelic Specifications Designer: A. H. -

A CRITICAL EVALUATION of the LOWER-MIDDLE PALAEOLITHIC ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECORD of the CHALK UPLANDS of NORTHWEST EUROPE Lesley

A CRITICAL EVALUATION OF THE LOWER-MIDDLE PALAEOLITHIC ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECORD OF THE CHALK UPLANDS OF NORTHWEST EUROPE The Chilterns, Pegsdon, Bedfordshire (photograph L. Blundell) Lesley Blundell UCL Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD September 2019 2 I, Lesley Blundell, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signed: 3 4 Abstract Our understanding of early human behaviour has always been and continues to be predicated on an archaeological record unevenly distributed in space and time. More than 80% of British Lower-Middle Palaeolithic findspots were discovered during the late 19th/early 20th centuries, the majority from lowland fluvial contexts. Within the British planning process and some academic research, the resultant findspot distributions are taken at face value, with insufficient consideration of possible bias resulting from variables operating on their creation. This leads to areas of landscape outside the river valleys being considered to have only limited archaeological potential. This thesis was conceived as an attempt to analyse the findspot data of the Lower-Middle Palaeolithic record of the Chalk uplands of southeast Britain and northern France within a framework complex enough to allow bias in the formation of findspot distribution patterns and artefact preservation/discovery opportunities to be identified and scrutinised more closely. Taking a dynamic, landscape = record approach, this research explores the potential influence of geomorphology, 19th/early 20th century industrialisation and antiquarian collecting on the creation of the Lower- Middle Palaeolithic record through the opportunities created for artefact preservation and release. -

Gazetteer.Doc Revised from 10/03/02

Save No. 91 Printed 10/03/02 10:33 AM Gazetteer.doc Revised From 10/03/02 Gazetteer compiled by E J Wiseman Abbots Ann SU 3243 Bighton Lane Watercress Beds SU 5933 Abbotstone Down SU 5836 Bishop's Dyke SU 3405 Acres Down SU 2709 Bishopstoke SU 4619 Alice Holt Forest SU 8042 Bishops Sutton Watercress Beds SU 6031 Allbrook SU 4521 Bisterne SU 1400 Allington Lane Gravel Pit SU 4717 Bitterne (Southampton) SU 4413 Alresford Watercress Beds SU 5833 Bitterne Park (Southampton) SU 4414 Alresford Pond SU 5933 Black Bush SU 2515 Amberwood Inclosure SU 2013 Blackbushe Airfield SU 8059 Amery Farm Estate (Alton) SU 7240 Black Dam (Basingstoke) SU 6552 Ampfield SU 4023 Black Gutter Bottom SU 2016 Andover Airfield SU 3245 Blackmoor SU 7733 Anton valley SU 3740 Blackmoor Golf Course SU 7734 Arlebury Lake SU 5732 Black Point (Hayling Island) SZ 7599 Ashlett Creek SU 4603 Blashford Lakes SU 1507 Ashlett Mill Pond SU 4603 Blendworth SU 7113 Ashley Farm (Stockbridge) SU 3730 Bordon SU 8035 Ashley Manor (Stockbridge) SU 3830 Bossington SU 3331 Ashley Walk SU 2014 Botley Wood SU 5410 Ashley Warren SU 4956 Bourley Reservoir SU 8250 Ashmansworth SU 4157 Boveridge SU 0714 Ashurst SU 3310 Braishfield SU 3725 Ash Vale Gravel Pit SU 8853 Brambridge SU 4622 Avington SU 5332 Bramley Camp SU 6559 Avon Castle SU 1303 Bramshaw Wood SU 2516 Avon Causeway SZ 1497 Bramshill (Warren Heath) SU 7759 Avon Tyrrell SZ 1499 Bramshill Common SU 7562 Backley Plain SU 2106 Bramshill Police College Lake SU 7560 Baddesley Common SU 3921 Bramshill Rubbish Tip SU 7561 Badnam Creek (River -

36 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

36 bus time schedule & line map 36 Lockerley View In Website Mode The 36 bus line (Lockerley) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Lockerley: 12:51 PM (2) Romsey: 9:26 AM - 1:26 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 36 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 36 bus arriving. Direction: Lockerley 36 bus Time Schedule 23 stops Lockerley Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday Not Operational Bus Station, Romsey Tuesday 12:51 PM Council O∆ces, Romsey Church Place, Romsey Wednesday Not Operational Malthouse Close, Romsey Thursday 12:51 PM Malthouse Close, Romsey Friday Not Operational Priestlands, Romsey Saturday Not Operational Greatbridge Road, Romsey Fishlake Meadows, Romsey Dukes Head, Belbins 36 bus Info Direction: Lockerley Timsbury Institute, Timsbury Stops: 23 Trip Duration: 34 min Recreation Ground, Michelmersh Line Summary: Bus Station, Romsey, Council O∆ces, Romsey, Malthouse Close, Romsey, Priestlands, Mannyngham Way, Michelmersh Romsey, Fishlake Meadows, Romsey, Dukes Head, Belbins, Timsbury Institute, Timsbury, Recreation Hill View Road, Michelmersh Ground, Michelmersh, Mannyngham Way, Michelmersh, Hill View Road, Michelmersh, Brickworks, Michelmersh, Bear And Ragged Staff, Brickworks, Michelmersh Kimbridge, Mottisfont Abbey, Mottisfont, Bengers Lane, Mottisfont, Village Hall, Mottisfont, Russell Bear And Ragged Staff, Kimbridge Drive, Dunbridge, Awbridge School, Kents Oak, Church Lane, Awbridge, Wood Farm, Kents Oak, Mottisfont Abbey, Mottisfont Newtown, Doctor's -

M+W Sites List (HF000007092018)

Hampshire County Council Site Code Site Name Grid Ref Operator / Agent Site Description Site Status Site Narrative (* = Safeguarded), (†=Chargeable site) Basingstoke and Deane Borough Council BA009 Newnham Common 470336 Hampshire County Council Landfill (restored) Site completed Restored non-inert landfill, closed in 1986 but subject to leachate monitoring not monitored (closed site, low priority) 153471 BA017† Apple Dell 451004 Portals Landfill (inert) Lapsed permission Dormant; deposit of non-toxic cellulose waste from paper making processes for a period of ten years (BDB46323) (Agriculture - 2009) Permission expired, no monitoring. Overton 148345 BA018* Wade Road 465127 Basingstoke Skip Hire, Hampshire County Council, Waste Processing, HWRC Active Waste transfer, including construction, demolition, industrial, household and clinical waste and household waste recycling centre; extension and improvement of household waste recycling Basingstoke 153579 Veolia Environmental Services (UK) Plc centre (BDB/60584); erection of waste recycling building (BDB/61845); erection of extension to existing waste recycling building (BDB/64564); extension and improvement of household waste recycling centre (BDB/69806) granted 12.2008 - 2 monitoring visits per year. BA019* Chineham Energy Recovery Facility 467222 Veolia Environmental Services (UK) Plc Waste Processing (energy Active Energy recovery incinerator (BDB044300) commissioned in autumn 2002 with handover in January 2003; the incinerator has the capacity to process at least 90,000 tonnes a year, -

The Middleton Estate

WELCOME TO THE MIDDLETON ESTATE Dear Angler, Welcome to the Middleton Estate! By now I hope you are settled and are relaxing with a cup of coffee. Here is a summary of the fishing and what to expect; have a lovely day. THE RIVER TEST The River Test has a total length of 40 miles and flows through the Hampshire downlands from its source near Overton, 6 miles to the west of Basingstoke, to the sea at the head of Southampton Water. The river rises in the village of Ashe, and flows west through the villages of Overton, Laverstoke, and the town of Whitchurch, before joining with the Bourne Rivulet at Testbourne and turning into a more southerly direction. It then flows through the villages of Longparish and Middleton to Wherwell and Chilbolton, where the Rivers Dever and Anton contribute to the flow. From Chilbolton the river flows through the villages of Leckford, Longstock, Stockbridge and Houghton to Mottisfont and Kimbridge, where the River Dun joins the flow. From here the village of Timsbury is passed, then through the grounds of Roke Manor before reaching the town of Romsey. On the western edge of Romsey, Sadler's Mill, an 18th Century watermill, sits astride the River Test. South of Romsey, the river flows past the country house of Broadlands, past Nursling that was once the site of a Roman bridge, and between Totton and Redbridge. Here the river is joined by the River Blackwater and soon becomes tidal, widening out into a considerable estuary that is lined on its northern bank by the container terminals and quays of the Port of Southampton. -

Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation Sincs Hampshire.Pdf

Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation (SINCs) within Hampshire © Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre No part of this documentHBIC may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recoding or otherwise without the prior permission of the Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre Central Grid SINC Ref District SINC Name Ref. SINC Criteria Area (ha) BD0001 Basingstoke & Deane Straits Copse, St. Mary Bourne SU38905040 1A 2.14 BD0002 Basingstoke & Deane Lee's Wood SU39005080 1A 1.99 BD0003 Basingstoke & Deane Great Wallop Hill Copse SU39005200 1A/1B 21.07 BD0004 Basingstoke & Deane Hackwood Copse SU39504950 1A 11.74 BD0005 Basingstoke & Deane Stokehill Farm Down SU39605130 2A 4.02 BD0006 Basingstoke & Deane Juniper Rough SU39605289 2D 1.16 BD0007 Basingstoke & Deane Leafy Grove Copse SU39685080 1A 1.83 BD0008 Basingstoke & Deane Trinley Wood SU39804900 1A 6.58 BD0009 Basingstoke & Deane East Woodhay Down SU39806040 2A 29.57 BD0010 Basingstoke & Deane Ten Acre Brow (East) SU39965580 1A 0.55 BD0011 Basingstoke & Deane Berries Copse SU40106240 1A 2.93 BD0012 Basingstoke & Deane Sidley Wood North SU40305590 1A 3.63 BD0013 Basingstoke & Deane The Oaks Grassland SU40405920 2A 1.12 BD0014 Basingstoke & Deane Sidley Wood South SU40505520 1B 1.87 BD0015 Basingstoke & Deane West Of Codley Copse SU40505680 2D/6A 0.68 BD0016 Basingstoke & Deane Hitchen Copse SU40505850 1A 13.91 BD0017 Basingstoke & Deane Pilot Hill: Field To The South-East SU40505900 2A/6A 4.62 -

INTRODUCTION by Peter Brigg

INTRODUCTION By Peter Brigg Fly fshing, not just for trout, is a multifaceted sport that will absorb you in its reality, it will take you to places of exceptional beauty, to explore, places to revel in the solitude and endless stimulation. He stands alone in the stream, a silver thread, alive, tumbling and Fly fshing, not just for trout, is a multifaceted sport that will absorb sliding in the soft morning light: around him the sights, sounds you in its reality, it will take you to places of exceptional beauty, to and smells of wilderness. Rod under his arm he carefully picks out explore, places to revel in the solitude and endless stimulation. Or, you a fy from amongst the neat rows, slides the fy box back into its vest can lose yourself between the pages of the vast literature on all facets pocket and ties on the small dry fy. Slowly, with poetic artistry he lifts of fy fshing, get absorbed by the history, the heritage, traditions and the rod and ficks the line out, gently landing the fy upstream of the skills, be transported in thought to wild places, or cast to imaginary diminishing circles of the feeding trout – watching, waiting with taut, fsh and gather knowledge. So often fy fshing is spoken of as an art quiet anticipation as the fy bobs and twirls on the current. form and having passed the half century of experience, I’m not averse to this view, just as I believe that fytying is inextricably linked to fy It is a scene we as fy fshers know well, a fascination and pre-occupation fshing, but is in its own right a craft, a form of artistry. -

American Fly Fisher (ISSN - ) Is Published Four Times a Year by the Museum at P.O

The America n Fly Fisher Journal of the American Museum of Fly Fishing Briefly, the Breviary William E. Andersen Robert A. Oden Jr. Foster Bam Erik R. Oken Peter Bowden Anne Hollis Perkins Jane Cooke Leigh H. Perkins Deborah Pratt Dawson Frederick S. Polhemus E. Bruce DiDonato, MD John Redpath Ronald Gard Roger Riccardi George R. Gibson III Franklin D. Schurz Jr. Gardner Grant Jr. Robert G. Scott James Heckman, MD Nicholas F. Selch Arthur Kaemmer, MD Gary J. Sherman, DPM Karen Kaplan Warren Stern Woods King III Ronald B. Stuckey William P. Leary III Tyler S. Thompson James Lepage Richard G. Tisch Anthony J. Magardino David H. Walsh Christopher P. Mahan Andrew Ward Walter T. Matia Thomas Weber William McMaster, MD James C. Woods Bradford Mills Nancy W. Zakon David Nichols Martin Zimmerman h c o H James Hardman David B. Ledlie - r o h William Herrick Leon L. Martuch c A y Paul Schullery h t o m i T Jonathan Reilly of Maggs Bros. and editor Kathleen Achor with the Haslinger Breviary in October . Karen Kaplan Andrew Ward President Vice President M , I received an e-mail from (page ), Hoffmann places the breviary’s Richard Hoffmann, a medieval scholar fishing notes in historical context. Gary J. Sherman, DPM James C. Woods Lwho has made multiple contribu - In October, with this issue already in Vice President Secretary tions to this journal, both as author and production, I made a long overdue trip to George R. Gibson III translator. He had been asked to assess a London. Before leaving, I contacted Treasurer text in a mid-fifteenth-century codex—a Jonathan Reilly of Maggs Bros. -

Esconet Text Retrieval System

EscoNet Text Retrieval System TEST VALLEY BOROUGH COUNCIL - PLANNING SERVICES WEEKLY LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS AND NOTIFICATIONS : NO. 40 Week Ending: Friday, 1 October 2004 Comments on any of these matters should be forwarded IN WRITING to arrive before the expiry date shown in the last column For the Northern Area (TVN) to: For the Southern Area (TVS) to Head of Planning Head of Planning Council Offices 'Beech Hurst' Duttons Road Weyhill Road ROMSEY SO51 8XG ANDOVER SPIO 3AJ In accordance with the provisions of the Local Government (Access to Information Act) 1985, any representations received may be open to public inspection PLANNING APPLICATIONS APPLICATION NO. / PROPOSAL LOCATION APPLICANT CASE OFFICER / REGISTRATION DATE PUBLICITY EXPIRY DATE http://www.minutes.org.uk/cgi-bin/cgi003.exe?Y,,,00000000000000100000...,,01.10.04,14223067,14295901,1,011004.HTM,1,1,1,P,67798058,0,00,00,N (1 of 6) [06/06/2013 17:03:40] EscoNet Text Retrieval System TVN.09223 Erection of rear conservatory 3 Elder Crescent, ABBOTTS ANN Mr S Grainger Maggie Francis 28.09.2004 Ms K M Auton 26.10.2004 TVN.09242 Erection of conservatory to rear 1 Stone Close, Andover Mr And Mrs Woodward Paul Goodman 28.09.2004 MILLWAY 26.10.2004 TVN.08963/1 Erection of two storey extension to 16 The Avenue, Andover Mr G Kitchen William Josey 28.09.2004 provide conservatory and garage MILLWAY Miss J Sellwood 26.10.2004 with bedroom and en-suite over TPO.00832/11 Gradual removal of whole conifer Tillers, Barncroft, APPLESHAW Mr And Mrs C & S Jones Dermot Cox 27.09.2004 hedge over a period of five years 26.10.2004 TVN.LB.00084/6 Installation of architectural lighting The Guildhall, High Street, Urban Projects Limited William Josey 27.09.2004 scheme Andover ST MARY'S 29.10.2004 TRE.CA.00587/97 Cotoneaster tree - Shorten back Fleur De Lys, AMPORT Andrew Douglas 27.09.2004 some branches on house side by one 26.10.2004 third.