The Film Adaptation of a River Runs Through It

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I'm Here Today As the Extraterrestrial Being of This Conference—As The

\)l AJLQJLI^ . I’m here today as the extraterrestrial being of this conference—as the shaggy example of what iate a Dupuyer life-form transmogrifies into when it*s transplanted away from the character-building" of the world off Montana. As I savvy it, I*ve come wuffling down out of the dark echoing canyons of space beyond Montana to try and deal with the great cosmic question—is there literary life west of Missoula? Because it is ordained somewhere that a speech is supposed to have a title, I told Margaret Kingsland I’d be talking today about "Browning, Conrad and Other World Centers." i What I have in mind when I say "world centers" are not the cosmopolitan capitals of the planet—although any of you who know something of my past, or who have spent time up in the Two Medicine country, will have some idea of how vseemed^ uptown Browning and ^onracTjiw^to a kid on a Dupuyer sheep ranch. No, the type of "world centers" I have in mind are those centralities from which each of us looks out at life—the influences that are at the core of what we end up doing in life. My belief is that part of the gauging of where we are—where we stand now, each one^of us a personal pivot point that some larger world of existence does its orbiting around—part of that gauging of ourselves means taking a look at where we came from. In "Dancing at the Rascal Fair" my narrator's closest friend spoofs him about his interest in the "Biaetefecfr 'and --Gewi s- an&.JlLgrig~-ay»4~ v for himself and me,^ ’’Angus, you're a great one for yesterdays.” And Angus says back to him,J^ "They ’ve brought us to where we are.” _think Ij __ 9k in that same vein,"~I^ougHt to begin here by looking at 9mm exanples of Browning and Conrad as ’’world centers” to me, in the way, say, that a biographer would rummage into my early years in Montana, in search of the influences that eventually brought forth my books. -

Norman Maclean (1902 - 1990)

Introducing 2012 Montana Cowboy Hall of Fame Inductee… Norman Maclean (1902 - 1990) Norman Fitzroy Maclean was an American author and scholar noted for his books A River Runs Through It and Other Stories (1976) and Young Men and Fire (1992). Born in Clarinda, Iowa, on December 23, 1902, Maclean was the son of Clara Evelyn (née Davidson; 1873-1952) and the Reverend John Norman Maclean (1862-1941), a Presbyterian minister, who managed much of the education of the young Norman and his brother Paul Davidson (1906-1938) until 1913. His parents had migrated from Nova Scotia, Canada. After Clarinda, the family relocated to Missoula, Montana in 1909. The following years were a considerable influence on and inspiration to his writings, appearing prominently in the short story The Woods, Books, and Truant Officers (1977), and semi-autobiographical novella A River Runs Through It (1976). Too young to enlist in the military during World War I, Maclean worked in logging camps and for the United States Forest Service in what is now the Bitterroot National Forest of northwestern Montana. The novella USFS 1919: The Ranger, the Cook, and a Hole in the Sky and the story "Black Ghost" in Young Men and Fire (1992) are semi- fictionalized accounts of these experiences. Maclean attended Dartmouth College, where he served as editor-in-chief of the humor magazine the Dartmouth Jack-O- Lantern; the editor-in-chief to follow him was Theodor Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss. He received his Bachelor of Arts in 1924, and chose to remain in Hanover, New Hampshire, and serve as an instructor until 1926—a time he recalled in "This Quarter I Am Taking McKeon: A Few Remarks on the Art of Teaching." He began graduate studies in English at the University of Chicago in 1928. -

Radio Essentials 2012

Artist Song Series Issue Track 44 When Your Heart Stops BeatingHitz Radio Issue 81 14 112 Dance With Me Hitz Radio Issue 19 12 112 Peaches & Cream Hitz Radio Issue 13 11 311 Don't Tread On Me Hitz Radio Issue 64 8 311 Love Song Hitz Radio Issue 48 5 - Happy Birthday To You Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 21 - Wedding Processional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 22 - Wedding Recessional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 23 10 Years Beautiful Hitz Radio Issue 99 6 10 Years Burnout Modern Rock RadioJul-18 10 10 Years Wasteland Hitz Radio Issue 68 4 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night Radio Essential IssueSeries 44 Disc 44 4 1975, The Chocolate Modern Rock RadioDec-13 12 1975, The Girls Mainstream RadioNov-14 8 1975, The Give Yourself A Try Modern Rock RadioSep-18 20 1975, The Love It If We Made It Modern Rock RadioJan-19 16 1975, The Love Me Modern Rock RadioJan-16 10 1975, The Sex Modern Rock RadioMar-14 18 1975, The Somebody Else Modern Rock RadioOct-16 21 1975, The The City Modern Rock RadioFeb-14 12 1975, The The Sound Modern Rock RadioJun-16 10 2 Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 4 2 Pistols She Got It Hitz Radio Issue 96 16 2 Unlimited Get Ready For This Radio Essential IssueSeries 23 Disc 23 3 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 16 21 Savage Feat. J. Cole a lot Mainstream RadioMay-19 11 3 Deep Can't Get Over You Hitz Radio Issue 16 6 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun Hitz Radio Issue 46 6 3 Doors Down Be Like That Hitz Radio Issue 16 2 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes Hitz Radio Issue 62 16 3 Doors Down Duck And Run Hitz Radio Issue 12 15 3 Doors Down Here Without You Hitz Radio Issue 41 14 3 Doors Down In The Dark Modern Rock RadioMar-16 10 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time Hitz Radio Issue 95 3 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Hitz Radio Issue 3 9 3 Doors Down Let Me Go Hitz Radio Issue 57 15 3 Doors Down One Light Modern Rock RadioJan-13 6 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone Hitz Radio Issue 31 2 3 Doors Down Feat. -

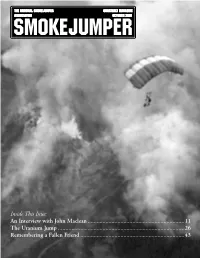

Inside This Issue: an Interview with John Maclean

The National Smokejumper Quarterly Magazine SmokejumperAssociation October 2001 Inside This Issue: An Interview with John Maclean .................................................................11 The Uranium Jump .....................................................................................26 Remembering a Fallen Friend ......................................................................43 Check the NSA Web site 1 www.smokejumpers.com CONTENTS Observations from the Ad Shack .................. 2 Observations Election Results ........................................... 2 My Brush with History/CPS 103 Jumpers ..... 3 NSA Members—Save This Information ........ 3 from the Ad Shack My Highest Jump and the Hospitality of the Silver Tip Ranch ........................ 5 Sounding Off from the Editor ....................... 8 Smokejumper magazine. A Commitment to Art Jukkala ...................... 9 At our June board meeting, “Army Brat” Commands Active Legion Post .................................................. 10 Fred Rohrbach and others An Interview with John Maclean, author suggested that the NSA should of Fire on the Mountain .................. 11 Down Side ................................................. 13 not wait five years to host The Night Pierce Burned ............................ 17 another reunion. None of us are Idaho City Jumps the Fires of Hell ............. 18 Is There Life After Smokejumping? ............ 19 getting any younger and, besides, Lois Stover ... Memories ............................ 20 we all seem to -

Hot Water, Dry Streams: a Tale of Two Trout

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All In-stream Flows Material In-stream Flows 2010 Hot Water, Dry Streams: A Tale of Two Trout Jack R. Tuholske Vermont Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/instream_all Part of the Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Tuholske, Jack R., "Hot Water, Dry Streams: A Tale of Two Trout" (2010). All In-stream Flows Material. Paper 8. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/instream_all/8 This Publication is brought to you for free and open access by the In-stream Flows at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All In-stream Flows Material by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOT WATER, DRY STREAMS: A TALE OF TWO TROUT Jack R. Tuholske ∗† INTRODUCTION Norman Maclean’s timeless memoir A River Runs Through It begins with the reflection that in his household “there was no clear line between religion and fly fishing.” 1 That zeal remains today; nearly 30 million Americans call themselves fishermen. 2 Anglers devoted an aggregate of 517 million user-days pursuing their passion in 2006 and spent billions of dollars to support it. 3 Fishing in the western United States holds a special place in fishing lore the world over and for good reason. From the great trout waters of Montana, to the salmon-laden rivers of the west coast, to the sparkling wilderness of the Colorado Rockies, fishing in the American West is special. Many native trout and salmon in the West are also on the verge of collapse. -

Vol. 35, No. 3, Summer, 2009

! The American Fly Fisher Journal of the American Museum of Fly Fishing SUMMER 2009 VOLUME 35 NUMBER 3 Traveling OR MANY, SUMMER is a season for And in Notes from the Library (page 24), traveling, and this issue takes you to Jerry Karaska reviews Ken Callahan and FArgentina and New Mexico—places Paul Morgan’s important updated resource, THE AMERICAN MUSEUM to which German brown trout traveled Hampton’s Angling Biography: Fishing Books OF FLY FISHING before you. 1881–1949 (The Three Beards Press, 2008). Preserving the Heritage Our two feature articles are both, in Both the museum and the fly-fishing part, about the success of nonnative fish world have lost some greats of late. Mel of Fly Fishing introduced to new waters. In “A Hundred Krieger, famed casting instructor and 2003 Years of Solitude: The Genesis of Trout recipient of this museum’s Heritage Award, FRIENDS OF THE MUSEUM Fishing in Argentina,”Adrian Latimer takes passed away in October; see page 20 for Robert Brucker (’08) us to Patagonia, offering first a bit of geo- Marshall Cutchin’s note. In January, we lost Austin Buck (’08) logical history, then some history about the Marty Keane, noted author, historian, and Larry Cohen (’08) importing of fish during the early part of purveyor of classic tackle. He was a major Domenic DiPiero (’08) the twentieth century. He notes that supporter of the museum, providing iden- John Dreyer (’08) although the lakes and rivers seemed per- tification, authentication, and appraisals for Fredrik Eaton (’08) fect for trout, there weren’t any, and “Thus us (see our notice on page 21). -

All Results Encore Performing Arts Showcase, Inc. June 21-25, 2021

Encore Performing Arts Showcase, Inc. All Results June 21-25, 2021 Henderson, NV, USA Green Valley Ranch Resort Division 1 Mini Solo Place Entry # Roune Name Studio 1 817 A Million Dreams Unique Performing Arts 2 820 Survivor Expressive Movement Dance 3 813 POWER Rancho Belago Dance Company 4 810 Buermilk Biscuts Unique Performing Arts 5 812 I've Got The Music In Me Dance Dynamics 6 816 WIND IT UP Rancho Belago Dance Company 7 818 I'm Cute Dance Dynamics 8 809 Jazz Baby Dance Dynamics 9 804 Diamond in the Sun Lonestar Collecve Dance 10 807 Friend Like Me Expressive Movement Dance Division 1 Mini D/T Place Entry # Roune Name Studio 1 845 Shake the Room Dance West 2 851 Get Happy Dance Dynamics 3 849 Burning Love Unique Performing Arts 4 843 Give A Lile Whistle Dance Dynamics 5 844 Castle on a Cloud Expressive Movement Dance 6 850 Jazzercise Babies Premiere Dance Company 7 852 Cooes Expressive Movement Dance 8 848 SOUR CANDY Rancho Belago Dance Company 9 846 Chiquita Banana Effusion Dance Center 10 847 So Very Glad You're Here Expressive Movement Dance Division 1 Petes Solo Place Entry # Roune Name Studio 1 836 I See The Light Dance Dynamics 2 825 Supergirl A Time To Dance 3 839 Emergency Unique Performing Arts 4 842 Glier Shoes Laura's Dance Dynamics 5 822 HIT IT FERGIE Rancho Belago Dance Company 6 829 Swagger Jagger QC Dance 7 835 Shake Senora Unique Performing Arts 8 828 Belle and Boujee Creave Edge Dance Studio 9 821 How Far I'll Go Unique Performing Arts 10 840 Fergalicious Expressions Dance & Music Division 1 Pete D/T Place Entry -

The Grace of Art in a River Runs Through It

There, in the Shadows: The Grace of Art in A River Runs Through It “Any man - any artist, as Nietzsche or Cezanne would say - climbs the stairway in the tower of his perfection at the cost of a struggle with a duende - not with an angel, as some have maintained, or with his muse. This fundamental distinction must be kept in mind if the root of a work of art is to be grasped.” Frederico Garcia Lorca Don Michael Hudson King College One more summer is closing quickly, and one more summer I have not made my annual pilgrimage to Montana. I live in the south again, happily this time, and it is well-nigh September, and even though the days are hot and muggy these very same days betray certain changes to come. The air is a bit drier, almost crisp; the bitter black walnuts are thumping the ground like some mad god thumping the earth; the days are growing shorter and darker; and yet, the leaves on some of the trees are stirring belly side up sending out silvery flickerings even as twilight sets in. Maybe that is why Montana is on my mind or, rather, why Norman Maclean is. I come back to him every August whether I make it to Montana or not. Since the summer of 1995 off and on I have been fishing a section of the Blackfoot River that I will not divulge, but suffice it to say that I am one of the luckiest men on the face of this earth if for no other reason than I discovered Maclean early on, and in so doing, I found a river and a way to bring grace and art to my life. -

TURN IT up DANCE CHALLENGE Long Island, NY (2Nd) WEST ISLIP - April 15-17, 2016

TURN IT UP DANCE CHALLENGE Long Island, NY (2nd) WEST ISLIP - April 15-17, 2016 Entry ID Class/ Level Age Category 1 Entry Type Routine Title Awards Studio Name 1 Competitive Teen Large Group LITTLE SHOP OF HORRORS High Gold Stars of Tomorrow Dance Academy 2 Competitive Teen Solo YOU PULLED ME THROUGH High Gold Jan Martin Dance Studio 3 Competitive Sr Teen Solo UNTIL WE GO DOWN High Gold Expressions in dance 4 Competitive Sr Teen Duo/Trio THESE FOUR WALLS Gold M&T Dance Unlimited 5 Recreational Teen Small Group AMERICANO High Gold dancehampton 6 Competitive Teen Solo SOMETHING IN THE WATER High Gold Expressions in dance 7 Competitive Junior Solo SHOW YA HOW High Gold Cristina's Dance Unlimited 8 Competitive Junior Small Group DESSERT Platinum Expressions in dance 9 Competitive Junior Duo/Trio FINNA GET LOOSE High Gold M&T Dance Unlimited 10 Competitive Junior Large Group SALUTE High Gold Jan Martin Dance Studio 11 Competitive Junior Solo ROTTEN TO THE CORE Gold Cristina's Dance Unlimited 12 Recreational Teen Solo THE VOICE WITHIN High Gold The Dance Place 13 Competitive Junior Solo SEE ME NOW High Gold Stars of Tomorrow Dance Academy 14 Recreational Junior Solo SUPERGIRL High Gold The Dance Place 15 Competitive Teen Solo TOTAL ECLIPSE OF THE HEART Platinum M&T Dance Unlimited 16 Competitive Teen Solo ANOTHER DAY IN PARADISE High Gold The Dance Place 17 Competitive Teen Duo/Trio WORK High Gold Jan Martin Dance Studio 18 Competitive Sr Teen Small Group IN THIS SHIRT High Gold Expressions in dance 19 Competitive Junior Duo/Trio I BELIEVE -

Journal of the American Museum of Fly Fishing

The American Fly Fisher Journal of the American Museum of Fly Fishing WINTER 2006 VOLUME 32 NUMBER 1 A Storied Sport The Salmon, painted by T. C. Hofland, in T. C. Hofland, Esq., The British Angler’s Manual (London: H. B. Bond, 1848, 24). HE STORY OF FLY FISHING is the story of beautiful places, a Fly Fisherman: The Marvels of Wood,” Masseini profiles the story of the nice neighborhoods that trout and woodworker Giorgio Dallari, builder of pipes and wooden Tsalmon call home. It’s a materialistic story, both in the reels. Dallari’s pipes have a tiny salmon icon set in gold to con- sense of the physical tools we use to accomplish the task and nect pipe smoker with fly fisher. The idea to build wooden the types of access and accommodation money can buy. It’s a reels came to Dallari after he gave up other forms of fishing for spiritual story, as men and women search out the river, its chal- fly fishing. He has been building his reels since the mid-1980s. lenges, its rewards, and its peace. It’s the story of struggle With sumptuous photos, Masseini shares the work of Giorgio toward some things and struggle against others. It’s the story Dallari with us. This story begins on page 17. of a sport, with both its obvious outward goals and its more From the material beauty of wooden reels to the more inward, metaphoric ones. abstract beauty of the spiritual reach, we present “The Last This issue of the American Fly Fisher touches a bit on all of Religious House: A River Ran Through It” (page 14). -

American Fly Fisher Journal of the American Museum of Fly Fishing

The American Fly Fisher Journal of the American Museum of Fly Fishing SUMMER 2008 VOLUME 34 NUMBER 3 In the Spirit of Rivers F THERE IS ANY time of year when we northern-hemisphere anglers might be found standing midriver, meditatively Icasting, and—as a direct result of this—allowing a feeling that could possibly be labeled spiritual or religious to seep in ever so slightly, it is right now. Summer. It was last summer that I met Sam Snyder, a Ph.D. candidate in the University of Florida’s graduate program on religion and nature. He and I were beginning to work on the article featured in this issue, and he was visiting the museum to do some research. Not only did his visit happily coincide with one from writer/historian Paul Schullery, whom Snyder cites prominent- ly, but also with a surprise visit from writer/Fly Fisherman edi- tor John Randolph, whose work Snyder discusses as well. Museum staff shared a sunny lunch at the picnic table with these three fly-fishing authors. It was a good day. In the aforementioned article, “Casting for Conservation: Religious Values and Environmental Ethics in Fly-Fishing Cul - ture,” Snyder asks, “Is fly fishing a religion? And what is accom- plished by considering it so?” He argues that fly-fishing faith can translate directly into works: conservation, restoration, and preservation. For more on the subject, turn to page 8. Turning from the philosophical to the literary, we’re pleased to bring you a rather unusual piece from our dear friend Gordon M. -

Water and People: Challenges at the Interface of Symbolic and Utilitarian Values

United States Department of Water and People: Challenges Agriculture Forest Service at the Interface of Symbolic Pacific Northwest and Utilitarian Values Research Station General Technical Report PNW-GTR-729 January 2008 The Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture is dedicated to the principle of multiple use management of the Nation’s forest resources for sus- tained yields of wood, water, forage, wildlife, and recreation. Through forestry research, cooperation with the States and private forest owners, and manage- ment of the national forests and national grasslands, it strives—as directed by Congress—to provide increasingly greater service to a growing Nation. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W. Washington, DC 20250-9410, or call (800) 795- 3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Editors Stephen F. McCool was a professor (now retired) of Wildland Recreation Manage- ment, College of Forestry, University of Montana, Missoula, MT 59812.