Research-Journal-Fall-2017.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read an Excerpt

The Artist Alive: Explorations in Music, Art & Theology, by Christopher Pramuk (Winona, MN: Anselm Academic, 2019). Copyright © 2019 by Christopher Pramuk. All rights reserved. www.anselmacademic.org. Introduction Seeds of Awareness This book is inspired by an undergraduate course called “Music, Art, and Theology,” one of the most popular classes I teach and probably the course I’ve most enjoyed teaching. The reasons for this may be as straightforward as they are worthy of lament. In an era when study of the arts has become a practical afterthought, a “luxury” squeezed out of tight education budgets and shrinking liberal arts curricula, people intuitively yearn for spaces where they can explore together the landscape of the human heart opened up by music and, more generally, the arts. All kinds of people are attracted to the arts, but I have found that young adults especially, seeking something deeper and more worthy of their questions than what they find in highly quantitative and STEM-oriented curricula, are drawn into the horizon of the ineffable where the arts take us. Across some twenty-five years in the classroom, over and over again it has been my experience that young people of diverse religious, racial, and economic backgrounds, when given the opportunity, are eager to plumb the wellsprings of spirit where art commingles with the divine-human drama of faith. From my childhood to the present day, my own spirituality1 or way of being in the world has been profoundly shaped by music, not least its capacity to carry me beyond myself and into communion with the mysterious, transcendent dimension of reality. -

Translation Rights List Non-Fiction

TRANSLATION RIGHTS LIST NON-FICTION Frankfurt Book Fair 2016 General Non-Fiction……………………….……...........p.2 Business and Management……………………...……p.8 History……………………………………………………..p.10 Memoirs and Biography……………………………….p.15 Modern Life……………………………………………….p.20 Health, Self-help and Popular Psychology……….....p.21 Parenting…………………………………………………..p.27 Food and Cookery……..…………………….….………p.29 Overcoming Series………………………………………p.32 ANDY HINE Rights Director (for Brazil, Germany, Italy, Poland, Scandinavia, Latin America and the Baltic States) [email protected] KATE HIBBERT Rights Director (for the USA, Spain, Portugal, Far East and the Netherlands) [email protected] HELENA DOREE Senior Rights Manager (for France, Turkey, Arab States, Israel, Greece, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Slovak Republic, Hungary, Romania, Russia, Serbia and Macedonia) [email protected] JOE DOWLEY Rights Assistant [email protected] Little, Brown Book Group Ltd Carmelite House 50 Victoria Embankment London EC4Y 0DZ Tel: +44 020 3122 6209 email: [email protected] Rights sold displayed in parentheses indicates that we do not control the rights * Indicates new title since previous Rights list Titles in italics were not published by Little, Brown Book Group GENERAL NON-FICTION BREAKING DOWN THE WALLS OF HEARTACHE by Martin Aston Popular culture | 592pp | 16pp colour and b&w picture section | Constable | October 2016 | Korea: | Japan: EAJ The very first history of gay popular music Popular music’s gay DNA is inarguable, from Elvis in eye shadow and Little Richard’s ‘Tutti Frutti’ to The Velvet Underground’s subversive rock’n’roll and Bowie’s ambisexual alien Ziggy Stardust; from disco diva Sylvester and Frankie Says ‘Relax’ to Frankie Knuckles; from Boy George to Morrissey’s ‘fourth sex’; from k.d. -

Capricor Phil Walden

August 6, 1993 ISSUE #337 $6.95 708 Stokes Road Medford, N J 08055 609-654-7272 609-654-6852 TOP PRIORITY LILLIAN AXE Capricor LILLIAN AXE Phil CRUCIFIED HARD ACT TO FOLLOW Walden BLACKEIS' SWEET SIXTEEN ALTERNATIVE PICK THE OCEAN BLUE SUBLIME HARD HITTEF INSIDE: • FROM OTIS REDDING TO THE ALLMANS AND WIDESPREAD PANIC--PHIL WALDEN HAS SEEN THAT AND MOORE bnins • END OF AN ERA: COX LMA'S TAMPA ROCK LEGEND WYNF WITH CHANGE TO HOT AC SUNNY 95 RUMORED al INFINITY 2ND QUARTER EARNINGS PROMPT 3 FOR 2 SPLIT II RANDY HOCK TO LEAVE MCA FOR DEAL WITH DENNY SOMA CH t.sNe ▪ KUKQ DROPS NEW ROCK FORMAT, WILL SIMUL KIFPD FOR NOW • LISA MICHAELSON IS ELEKTRA'S NEW NACAIAZZ/AAA MGR. • BARNES, BETTS, CURELOP, EDWARDS, HUGHES, JANG, LOGAN, LUCZAK, MCNUTT, OWEN AND MORE MEET FOR CANOE CARNEY 93! dAD B r RISE/UNIDENTIFIED TOP PRIORITY illian Axe, "Crucified", I.R.S. Last year Poetic Justice hit sales figures in excess of 120,000 with corresponding chart success along the way. Lillian Axe has been blessed with the talent to write great Lsongs, work hard, pay their dues, and break into the AOR ranks with solid singles like "True Believer" and "No Mailer What". Psychoschizophrenia will likely take the band to the next level with hard hitting "Crucified" as a first release. Steve's guitar blazes once again as he incorporates his classical training and a terrific edge to the album. Steve takes Axe's sound to a darker, heavier place with results that are already paying oft Early action at WWBZ, WRZK, KZRX, WVCR and WKLO have people like John Edwards at the Blaze admitting, "It has just the right texture for us." KLQ's Dave Wellington adds, "I'm really impressed with the sound of their new stuff" We think you'll agree HARD ACTS TO FOLLO W ishbone, "Unyielding Conditioning", Columbia Fis/ibones forte has always been „ ve performances. -

The Writeidea Festival 2016 East London’S FREE Reading Festival

The Writeidea Festival 2016 East London’s FREE Reading Festival 11-13 November 2016 East The London’s FREE Writeidea Reading Festival Festival 2016 11-13 November 2016 www.towerhamlets.gov.uk/writeideahttp://writeideafestival.org INTRODUCTION Welcome to the eighth East End myths and history, edition of the Writeidea real and imagined detectives, Festival, Tower Hamlets travellers, revolutionaries, Council’s unique free music icons, and plenty of reading festival. fascinating stories to fill us all with wonder. Local history is Once again, this is truly a always a popular theme at people’s event, with many Writeidea, so look out for the authors suggested by local strand of talks on Saturday people, and others chosen 12 November, programmed from an ever wider range by our colleagues at Tower of fiction and non-fiction Hamlets Local History writers and performers. Library & Archives, on Our free-entry policy has Bancroft Road. proved very popular in the past, and we are confident By now regular festival this year we will again see goers will know that you can new people alongside those prepare for the Writeidea who regularly enjoy literary by reading all the authors’ events. books for free - you just need an Idea Store card We are very grateful to the (also free) to borrow them. Arts Council of England for If you really liked a book and their continued support, and want to have your own copy, to the Canary Wharf Group you can purchase one during for their contribution. the festival weekend at the We are particularly pleased stall provided by Brick Lane to kick off events on Friday Books, our independent, local bookshop. -

Glam Rock by Barney Hoskyns 1

Glam Rock By Barney Hoskyns There's a new sensation A fabulous creation, A danceable solution To teenage revolution Roxy Music, 1973 1: All the Young Dudes: Dawn of the Teenage Rampage Glamour – a word first used in the 18th Century as a Scottish term connoting "magic" or "enchantment" – has always been a part of pop music. With his mascara and gold suits, Elvis Presley was pure glam. So was Little Richard, with his pencil moustache and towering pompadour hairstyle. The Rolling Stones of the mid-to- late Sixties, swathed in scarves and furs, were unquestionably glam; the group even dressed in drag to push their 1966 single "Have You Seen Your Mother, Baby, Standing in the Shadow?" But it wasn't until 1971 that "glam" as a term became the buzzword for a new teenage subculture that was reacting to the messianic, we-can-change-the-world rhetoric of late Sixties rock. When T. Rex's Marc Bolan sprinkled glitter under his eyes for a TV taping of the group’s "Hot Love," it signaled a revolt into provocative style, an implicit rejection of the music to which stoned older siblings had swayed during the previous decade. "My brother’s back at home with his Beatles and his Stones," Mott the Hoople's Ian Hunter drawled on the anthemic David Bowie song "All the Young Dudes," "we never got it off on that revolution stuff..." As such, glam was a manifestation of pop's cyclical nature, its hedonism and surface show-business fizz offering a pointed contrast to the sometimes po-faced earnestness of the Woodstock era. -

Rock Introductory Essay

Session Five: Rock Introductory Essay Charles F. McGovern, Associate Professor of American Studies and History, College of William and Mary The music we know as rock and roll emerged in the mid 1950s, although its advent had been on the horizon for at least a decade. A quarter of the American population moved during World War II, and that brought southern, rural, sacred and secular traditions into new contact with urban based music and audiences. The product of many regional musical scenes and independent record labels, rock and roll emerged in Memphis, Los Angeles, Shreveport, New York, Detroit, Baltimore, and dozens of other cities. It was, in historian Charlie Gillett’s words, the Sound of the City. Rock and roll drew on many different styles. Combining the boogie woogie rhythms of R&B, the hillbilly twang of country, the fervor of gospel and the moans of the blues, the new mongrel music excited a worldwide generation of young listeners, while upsetting established social, cultural and musical authorities. The charisma and musical bravado of early rock and roll heroes such as Elvis Presley, Chuck Berry and Little Richard inspired fans and young musicians alike. With the maturing of an unprecedentedly vast and affluent teenage audience, rock and roll music became the sound of young America and soon spread around the world. It is difficult today to understand the bitter criticism the new music generated. The popular music establishment, anchored in the lucrative venues of Hollywood and Broadway, saw the challenge as both aesthetic and economic. Their spokesmen dismissed the music for its supposed simplicity and crudity; eventually they went so far as to charge, falsely, that rock and roll dominated their airwaves because promoters bribed disc jockeys. -

Thesis University of London

THESIS UNIVERSITY OF LONDON COPYRIGHT This is a thesis accepted for a higher degree of the University of London. It has been made available to the Institute of Education library for public reference, photocopying and inter-library loan. The copyright is held by the author. All persons consulting the thesis must read and abide by the Copyright Declaration below. COPYRIGHT DECLARATION I recognise that the copyright of this thesis rests with the author and that no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. `I drum, therefore I am'? A study of kit drummers' identities, practices and learning Gareth Dylan Smith Institute of Education, University of London Submitted for PhD 1 ABSTRACT Drummers have largely been neglected in scholarly literature on music and education, despite being active in large numbers in popular music and having an increasing presence in the music education arena. The study explores the identities, practices and learning of kit drummers in the UK from an emic perspective, using a mixed methodological approach with a focus on qualitative sociological enquiry drawing on interpretative phenomenological analysis and grounded theory. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 15 teenage drummers and 12 adult drummers; both age groups were interviewed to allow for consideration of whether adults' reflections on their formative years differ greatly from those of teenage drummers today. Secondary data were gathered from a brief questionnaire conducted with 100 more drummers to support and contextualize the richer interview data. Data were also taken from relevant biographies, audio/visual media and journalistic sources. -

Van Morrison from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Van Morrison From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Background information Birth name George Ivan Morrison Also known as Van the Man, The Belfast Cowboy Born 31 August 1945 (age 69) Origin Belfast, Northern Ireland Genres Rock, blues, rhythm and blues, folk, blue-eyed soul, Celtic, rock and roll, jazz, pop, soft rock, country, skiffle, gospel Occupation(s) Singer-songwriter, musician Instruments Vocals, guitar, harmonica, saxophones, keyboards, drums, tambourine, ukulele Years active 1958–present Labels Decca, Bang, Warner Bros., London, Mercury, Exile/Polydor, Verve, Point Blank, Virgin, Universal, Blue Note, Lost Highway, Listen to the Lion/EMI, Manhattan, RCA (2014-present) George Ivan "Van" Morrison, OBE (born 31 August 1945) is a Northern Irish singer-songwriter and musician. Some of his recordings, such as the studio albums Astral Weeks and Moondance and the live album It's Too Late to Stop Now, are critically acclaimed. He has received six Grammy Awards, the Brit Award for Outstanding Contribution to Music, been inducted into both the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and the Songwriters Hall of Fame. Known as "Van the Man" to his fans, Morrison started his professional career when, as a teenager in the late 1950s, he played a variety of instruments including guitar, harmonica, keyboards and saxophone for various Irish showbands covering the popular hits of the day. He rose to prominence in the mid-1960s as the lead singer of the Northern Irish R&B band Them, with whom he recorded the garage band classic "Gloria". His solo career began under the pop-hit oriented guidance of Bert Berns with the release of the hit single "Brown Eyed Girl" in 1967. -

October 2020 New Releases

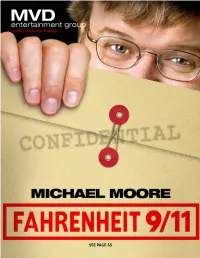

October 2020 New Releases SEE PAGE 55 what’s inside featured exclusives PAGE 3 RUSH Releases Vinyl Available Immediately 67 Music [MUSIC] Vinyl 3 CD 13 FEATURED RELEASES Video ANDREAS THE RESIDENTS - KIM WILSON - 39 VOLLENWEIDER- CUBE-E BOX TAKE ME BACK Film QUIET PLACES Films & Docs 40 MVD Distribution Independent Releases 65 Order Form 74 Deletions & Price Changes 72 THE OUTLAWS - THE LAST STARFIGHTER FAHRENHEIT 9/11 800.888.0486 LIVE AT ROCKPALAST 1981 203 Windsor Rd., Pottstown, PA 19464 www.MVDb2b.com THE DEAD MILKMEN - ANDREAS VOLLENWEIDER- OKEY DOKEY - (WE DON’T NEED THIS) FASCIST QUIET PLACES ONCE UPON ONE TIME GROOVE THANG (2ND PRESSING) OCTOBER HEAT WAVE! MVD turns up the hotness with FAHRENHEIT 9/11, the #1 best-selling documentary of all time! Available on DVD, and for the first time on bluray! Watch as Michael Moore bushwhacks his way through this controversial film about the relation between money, oil and the 9/11 tragedy, graced with a dash of satire. This new issue comes with lots of bonus features, reversible artwork and limited edition slipcover, scorching any prior version. While FAHRENHEIT’s temperature is elevated, ARROW VIDEO chills us with the limited bluray of COLD LIGHT OF DAY, a retelling of British serial killer Des Nilsen’s grisly story. Arrow’s THE DEEPER YOU DIG finds a body hidden in the cold, hard ground, only to have the murderer’s head burrowed into by the victim! A real headache! THE LAST STARFIGHTER, the 1984 Sci-Fi opus, gets the Arrow treatment this month, showing the computer whizz kid fighting an interstellar war with a new 4K scan and a stunning sound mix. -

Tom Waits: a Songwriter on the Edge Bachelor’S Diploma Thesis

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Filip Drlík Tom Waits: A Songwriter on the Edge Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: doc. PhDr. Tomáš Pospíšil, Dr. 2011 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Filip Drlík I would like to thank my supervisor, doc. PhDr. Tomáš Pospíšil, Dr. for being very helpful and supportive. I would also like to thank Romana for opening my mind for many different views. Table of contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Self-stylization .......................................................................................................................... 3 1.1. Influences ........................................................................................................................... 3 1.2. Self-stylization ................................................................................................................... 7 1.3. Authenticity ...................................................................................................................... 13 2. Reports from the Edge ............................................................................................................ 17 2.1. America’s Dark Side ....................................................................................................... -

Bibliography

BIbLIOGRAPHY “About | Glow.” Accessed June 2, 2015. http://glowsantamonica.org/about/. Abramson, Cynthia, Myrna Margulies Breitbart, and Pamela Worden. “Art and the Transit Experience/Creating a Sense of Purpose: Public Art and Boston’s Orange Line.” In Common Ground?: Readings and Refections on Public Space, edited by Anthony M. Orum and Zachary P. Neal, 1–10. New York: Routledge, 2010. AGAR. “AGAR.” Accessed June 8, 2020. https://www.theagar.com. Aitken, Doug. “Liquid Architecture: In Conversation with Hans Ulrich Obrist.” In Doug Aitken: 100YRS, 158–59. New York: Rizzoli, 2013. Albu, Cristina. Mirror Affect: Seeing Self, Observing Others in Contemporary Art. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017. Arnold, Alice, and Jason Eppink. “Electric Signs: An Interview with Jason Eppink, the Pixelator.” In Urban Screens Reader, edited by Scott McQuire, Meredith Martin, and Sabine Niederer, 217–20. INC Readers 5. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2009. “Artist’s Antiwar Message Censored.” Art in America, January 1984, 176. Atkinson, Sarah. “Post-Viral Cinema.” In Media Res Coronavirus and Cinematic Experience (June 15, 2020). http://mediacommons.org/imr/content/ post-viral-cinema. Augé, Marc. Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity. Translated by John Howe. New York: Verso, 1995. © The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature 265 Switzerland AG 2021 A. Dell’Aria, The Moving Image as Public Art, Experimental Film and Artists’ Moving Image, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-65904-2 266 BIBLIOGRAPHY Babcock, Stephen. “7 Startup-Centric Talks to Check out during Labs@Light City 2018.” Technical.ly Baltimore, April 11, 2018. https://technical.ly/ baltimore/2018/04/11/7-startup-centric-talks-check-labslight-city-2018/. -

Historyofrock'n'roll

HistoryofRock’n’Roll Professor WILLIAM McKEEN Office: Home; Phone: 595-7548 Email: wmckeen@ bu.edu Office hours: Tuesdays and Wednesdays, 1:30 - 3 pm and by appointment Home page: williammckeen.com Twitter: @wmckeen story of popular music. There will be a special emphasis on rock 'n' roll and its impact on America in the last 40 years, especially Summer 2021 Ersel Hickey, the the 1954-1970 era. quintessence of early rock’n’roll. Although this course is a lot of fun, it is not easy. HI 280 There is a lot of work. We have one required book: the course: music could bring people ✓ William McKeen, Rock and About this course together. Roll is Here to Stay (W.W. Norton, 2000). This course examines the role of We will study the origin and popular music in American growth of the recording For those of you who are music culture. geeks, I recommended these industry in the United States, but two: It is not a music course, but more focus most of our energies on of an examination of the effects tracing the threads of ✓ Charlie Gillett, The Sound of of recorded sound on popular mainstream music during the the City (Da Capo Press, 1996; culture. 20th century. second edition) In some ways, it’s a civil rights We will attempt to integrate the ✓ Greil Marcus, Mystery Train course and deals with the general social and intellectual (Plume, 2000; fifth edition) 1 struggle for integration and how history of the country into the Grading and other issues You will write a major research paper on an artist Speaking of class participation: It should go of your choice.