Riffs: Experimental Writing on Popular Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2ANGLAIS.Pdf

ANGLAIS domsdkp.com HERE WITHOUT YOU 3 DOORS DOWN KRYPTONITE 3 DOORS DOWN IN DA CLUB 50 CENT CANDY SHOP 50 CENT WHAT'S UP ? 4 NON BLONDES TAKE ON ME A-HA MEDLEY ABBA MONEY MONEY MONEY ABBA DANCING QUEEN ABBA FERNANDO ABBA THE WINNER TAKES IT ALL ABBA TAKE A CHANCE ON ME ABBA I HAVE A DREAM ABBA CHIQUITITA ABBA GIMME GIMME GIMME ABBA WATERLOO ABBA KNOWING ME KNOWING YOU ABBA TAKE A CHANCE ON ME ABBA THANK YOU FOR THE MUSIC ABBA SUPER TROUPER ABBA VOULEZ VOUS ABBA UNDER ATTACK ABBA ONE OF US ABBA HONEY HONEY ABBA HAPPY NEW YEAR ABBA HIGHWAY TO HELL AC DC HELLS BELLS AC DC BACK IN BLACK AC DC TNT AC DC TOUCH TOO MUCH AC DC THUNDERSTRUCK AC DC WHOLE LOTTA ROSIE AC DC LET THERE BE ROCK AC DC THE JACK AC DC YOU SHOOK ME ALL NIGHT LONG AC DC WAR MACHINE AC DC PLAY BALL AC DC ROCK OR DUST AC DC ALL THAT SHE WANTS ACE OF BASE MAD WORLD ADAM LAMBERT ROLLING IN THE DEEP ADELE SOMEONE LIKE YOU ADELE DON'T YOU REMEMBER ADELE RUMOUR HAS IT ADELE ONLY AND ONLY ADELE SET FIRE TO THE RAIN ADELE TURNING TABLES ADELE SKYFALL ADELE WALK THIS WAY AEROSMITH WALK THIS WAY AEROSMITH BECAUSE I GOT HIGH AFROMAN RELEASE ME AGNES LONELY AKON EYES IN THE SKY ALAN PARSON PROJECT THANK YOU ALANIS MORISSETTE YOU LEARN ALANIS MORISSETTE IRONIC ALANIS MORISSETTE THE BOY DOES NOTHING ALESHA DIXON NO ROOTS ALICE MERTON FALLIN' ALICIA KEYS NO ONE ALICIA KEYS Page 1 IF I AIN'T GOT YOU ALICIA KEYS DOESN'T MEAN ANYTHING ALICIA KEYS SMOOTH CRIMINAL ALIEN ANT FARM NEVER EVER ALL SAINTS SWEET FANTA DIALO ALPHA BLONDY A HORSE WITH NO NAME AMERICA KNOCK ON WOOD AMII STEWART THIS -

Cd Musicali – Rock Artisti Stranieri

CD MUSICALI – ROCK ARTISTI STRANIERI Leonard Cohen – Dear Heather R. E. M. – Around the Sun Steely Dan – Aja Yes – Close to the Edge Faiport Convention – Unhalfbricking MC 5 – Kick out the jams Black Sabbath – Paranoid The Strokers – Room on fire Jain Mitchell – Blue Bang Gang – Something wrong Jamiroquai – A fun adyssey Moby – I like to score Garky’s Zygotic Mynci – How long feel that summer in my heart Radiohead – I might be wrong live recording Bob Marley & The Wailers – Uprising Alanis Morisette – Under Rug Swept Lou Reed – NYC Man Blur – Think Tank Bill Bragg & Wilco – Mermaid Avenue Radioheah – Hai to the thief Peter Gabriel – Hit Elvis Costello – North The Rocking Chairs – Sparkes of Passion Rickie Lee Jones _ The evening of my best day The Rolling Stones – Beggars Banquet Robert Wyatt – Rock Bottom Patti Smith Group – Wave The Kills – Keep on your mean side Fairport Convention – Full house Era – Tha masy Belle e Sebastian – Dear catastrophe waitress Van Marrison – What’s wrong with this picture? Nick Drake – Tink Moon The Black Eyed Peas – Elephunk Tom Waits – Real Gone The Who – Live at Leeds Joy Division – Substance 1977 – 1980 Elliot Smith – Figure 8 Caravan – In the Land of Grey and Pink Happy Trails – Quicksilver Messenger Service The Allman Brothers Band – Eat a Peach Julian Cope – Fried Mudhoney – Superfuzz Bigmuff plus Early Singles Jane’s Addiction – Ritual de lo habitual 1 Eels – Daisies of the galaxy Mallard – In a different climate Frank Zappa – Over – nite Sensation Tom Waits – Blood Money Patty Smith – Land ( 1995 -

Stardigio Program

スターデジオ チャンネル:450 洋楽アーティスト特集 放送日:2019/09/23~2019/09/29 「番組案内 (8時間サイクル)」 開始時間:4:00~/12:00~/20:00~ 楽曲タイトル 演奏者名 ■TAYLOR SWIFT 特集 (1) Tim McGraw [Radio Edit] Taylor Swift PICTURE TO BURN [RADIO EDIT] Taylor Swift Teardrops On My Guitar [Pop Mix] Taylor Swift SHOULD'VE SAID NO Taylor Swift OUR SONG [SINGLE MIX] Taylor Swift I'M ONLY ME WHEN I'M WITH YOU Taylor Swift CHANGE Taylor Swift FEARLESS [SINGLE EDIT] Taylor Swift FIFTEEN [UK EDIT] Taylor Swift LOVE STORY Taylor Swift WHITE HORSE [RADIO EDIT] Taylor Swift YOU BELONG WITH ME [TOP 40 MIX] Taylor Swift TELL ME WHY Taylor Swift THE WAY I LOVED YOU Taylor Swift FOREVER & ALWAYS Taylor Swift YOU'RE NOT SORRY Taylor Swift ■TAYLOR SWIFT 特集 (2) BREATHE Taylor Swift feat. Colbie Caillat THE BEST DAY Taylor Swift Crazier Taylor Swift TWO IS BETTER THAN ONE [MAIN] Boys Like Girls feat. Taylor Swift HALF OF MY HEART JOHN MAYER with TAYLOR SWIFT TODAY WAS A FAIRYTALE Taylor Swift Jump Then Fall Taylor Swift MINE Taylor Swift Dear John Taylor Swift Never Grow Up Taylor Swift Enchanted Taylor Swift Long Live Taylor Swift BACK TO DECEMBER [RADIO EDIT] Taylor Swift ■TAYLOR SWIFT 特集 (3) Speak Now Taylor Swift Better Than Revenge Taylor Swift Innocent Taylor Swift Haunted Taylor Swift Last Kiss Taylor Swift MEAN Taylor Swift THE STORY OF US [UK RADIO EDIT] Taylor Swift SPARKS FLY Taylor Swift OURS Taylor Swift If This Was a Movie Taylor Swift Superman Taylor Swift BOTH OF US B.o.B feat. TAYLOR SWIFT SAFE & SOUND TAYLOR SWIFT feat. -

Bourdieu and the Music Field

Bourdieu and the Music Field Professor Michael Grenfell This work as an example of the: Problem of Aesthetics A Reflective and Relational Methodology ‘to construct systems of intelligible relations capable of making sense of sentient data’. Rules of Art: p.xvi A reflexive understanding of the expressive impulse in trans-historical fields and the necessity of human creativity immanent in them. (ibid). A Bourdieusian Methodology for the Sub-Field of Musical Production • The process is always iterative … so this paper presents a ‘work in progress’ … • The presentation represents the state of play in a third cycle through data collection and analysis …so findings are contingent and diagrams used are the current working diagrams! • The process begins with the most prominent agents in the field since these are the ones with the most capital and the best configuration. A Bourdieusian Approach to the Music Field ……..involves……… Structure Structuring and Structured Structures Externalisation of Internality and the Internalisation of Externality => ‘A science of dialectical relations between objective structures…and the subjective dispositions within which these structures are actualised and which tend to reproduce them’. Bourdieu’s Thinking Tools “Habitus and Field designate bundles of relations. A field consists of a set of objective, historical relations between positions anchored in certain forms of power (or capital); habitus consists of a set of historical relations ‘deposited’ within individual bodies in the forms of mental and corporeal -

The AGA Song Book up to Date

3rd Edition Songs, Poems, Stories and More! Edited by Bob Felice Published by The American Go Association P.O. Box 397, Old Chelsea Station New York, N.Y., 10113-0397 Copyright 1998, 2002, 2006 in the U.S.A. by the American Go Association, except where noted. Cover illustration by Jim Rodgers. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without prior written permission of the copyright holder, except for brief quotations used as part of a critical review. Introductions Introduction to the 1st Edition When I attended my first Go Congress three years ago I was astounded by the sheer number of silly Go songs everyone knew. At the next Congress, I wondered if all these musical treasures had ever been printed. Some research revealed that the late Bob High had put together three collections of Go songs, but the last of these appeared in 1990. Very few people had these song books, and some, like me, weren’t even aware that they existed. While new songs had been printed in the American Go Journal, there was clearly a need for a new collection of Go songs. Last year I decided to do whatever I could to bring the AGA Song Book up to date. I wanted to collect as many of the old songs as I could find, as well as the new songs that had been written since Bob High’s last song book. You are holding in your hands the book I was looking for two years ago. -

New Dvds – December - 2013

NEW DVDS – DECEMBER - 2013 FEATURE FILMS: GANGS OF NEW YORK A GOOD DAY TO DIE HARD BEFORE MIDNIGHT HOMELAND: SEASON 1 PACIFIC RIM TOO BIG TO FAIL SNITCH THE GREAT GATSBY GET THE GRINGO FREELANCERS LAWLESS THE CONJURING LORD OF THE FLIES SMASHED BYZANTIUM THE HALLOWEEN COLLECTION THE BOONDOCKS: SEASONS 1,2,3 HOMELAND: SEASON 2 THE ICEMAN SCHINDLER’S LIST PRINCE AVALANCHE WORLD WAR Z PEEPLES MEMENTO LUTHER LUTHER 2 IN THE FOG HUSBANDS AND WIVES THE LAST STAND KISS KISS BANG BANG THE ATTACK BEHIND THE CANDELABRA CURSE OF CHUCKY CLOUD ATLAS HOT FUZZ BARBARA ALIEN TRIPLE PACK SUPERBAD BLOW OUT HEAD OF STATE TRUST WHITE DAWN BREAKING BAD: FINAL SEASON REN & STIMPY SHOW UNCUT: SEASONS 1&2 RESOLUTION EASTERN PROMISES DOCUMENTARIES: THE WEIGHT OF THE NATION WE STEAL SECRETS RISE OF THE DRONES THE CENTRAL PARK FIVE RAISING ADAM LANZA THE WAITING ROOM CONSTITUTION USA MY TRIP TO AL-QAEDA LATINO AMERICANS CALL ME KUCHU GOOD HAIR KEY & PEELE: SEASON 1 COLIN QUINN: LONG STORY SHORT BLACKFISH I’M CAROLYN PARKER MEA MAXIMA CULPA CLIMATE OF DOUBT CHASING ICE INTO THE DEEP STRONGMAN THE DADDY OF ROCK N ROLL DECEPTIVE PRACTICE NEW MUSIC CD’s December 2013 POP Julia Holter Loud City Song Tye Tribbett Greater Than Drake Nothing Was the Same Darkside Psychic Tom Waits Bad as Me Bone Machine Justin Timberlake The 20/20 Experience Eccentric Soul The Forte Label Percy Sledge The Platinum Collection Valerie June Pushin Against a Stone Neko Case The Worse Things Get Janelle Monae The Electric Lady Velvet Underground 45th Anniversary Remaster Roky Erickson Gremlins Have Pictures COUNTRY Brandy Clark 12 Stories CLASSICAL Massimo Giordano Amore E Tormento WORLD Ana Tijoux La Bala Luis Coronel Con La Frente En Alto Rodion GA The Lost Tapes . -

Residential Property Owners As Of: 2/10/2021 Two and Three Family

Residential Property Owners as of: 2/10/2021 Two and Three Family Sect Taxkey Property Address Owner Name Secondary Owner Owner Address Owner CityState,Zip Property Use 32 415-0006-000 10006 W Bungalow Pkwy Aaron S. Jacobson Glenn Barber 671 S 100 St West Allis, WI 53214 940 Residential Duplex 32 415-0013-000 10202 W Bungalow Pkwy Ronald C. Shikora Doris J. Shikora 4085 Brook Ln Brookfield, WI 53005 940 Residential Duplex 32 416-0019-000 651 S 93 St Reddie Living Trust 651 S 93 St West Allis, WI 53214 940 Residential Duplex 32 416-0023-001 681 S 93 St Corry S. Eifert Sandra S. Eifert 2745 S 132 St New Berlin, WI 53151 940 Residential Duplex 32 416-9981-001 9732 W Schlinger Ave Shirley Kewan 9732 W Schlinger Ave West Allis, WI 53214 940 Residential Duplex 33 417-0009-000 9116 W Conrad Ln Jeffrey J. Raab N3430 County Rd K Jefferson, WI 53549 940 Residential Duplex 35 438-0001-000 705 S 57 St Gary J. Karabelas Carol A. Karabelas 6009 W Mitchell St West Allis, WI 53214 940 Residential Duplex 35 438-0009-000 804 S 58 St Santiago Rodriguez Iraviregen Rodriguez 804 S 58 St West Allis, WI 53214 940 Residential Duplex 35 438-0024-000 810 S 57 St Christopher J. Lake Rebecca T. Long-Lake PO Box 204 Big Bend, WI 53103 940 Residential Duplex 35 438-0029-004 702 S 57 St Jeffrey T. Anderson 125 N 70 St Milwaukee, WI 53213 940 Residential Duplex 35 438-0038-000 1000 S 58 St Gary L. -

Read an Excerpt

The Artist Alive: Explorations in Music, Art & Theology, by Christopher Pramuk (Winona, MN: Anselm Academic, 2019). Copyright © 2019 by Christopher Pramuk. All rights reserved. www.anselmacademic.org. Introduction Seeds of Awareness This book is inspired by an undergraduate course called “Music, Art, and Theology,” one of the most popular classes I teach and probably the course I’ve most enjoyed teaching. The reasons for this may be as straightforward as they are worthy of lament. In an era when study of the arts has become a practical afterthought, a “luxury” squeezed out of tight education budgets and shrinking liberal arts curricula, people intuitively yearn for spaces where they can explore together the landscape of the human heart opened up by music and, more generally, the arts. All kinds of people are attracted to the arts, but I have found that young adults especially, seeking something deeper and more worthy of their questions than what they find in highly quantitative and STEM-oriented curricula, are drawn into the horizon of the ineffable where the arts take us. Across some twenty-five years in the classroom, over and over again it has been my experience that young people of diverse religious, racial, and economic backgrounds, when given the opportunity, are eager to plumb the wellsprings of spirit where art commingles with the divine-human drama of faith. From my childhood to the present day, my own spirituality1 or way of being in the world has been profoundly shaped by music, not least its capacity to carry me beyond myself and into communion with the mysterious, transcendent dimension of reality. -

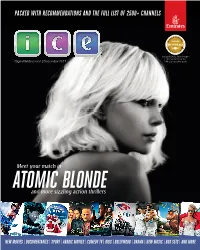

Packed with Recommendations and the Full List of 2500+ Channels

PACKED WITH RECOMMENDATIONS AND THE FULL LIST OF 2500+ CHANNELS Voted World’s Best Infl ight Entertainment for the Digital Widescreen | December 2017 13th consecutive year! Meet your match in ATOMIC BLONDE and more sizzling action thrillers NEW MOVIES | DOCUMENTARIES | SPORT | ARABIC MOVIES | COMEDY TV | KIDS | BOLLYWOOD | DRAMA | NEW MUSIC | BOX SETS | AND MORE OBCOFCDec17EX2.indd 51 09/11/2017 15:13 EMIRATES ICE_EX2_DIGITAL_WIDESCREEN_62_DECEMBER17 051_FRONT COVER_V1 200X250 44 An extraordinary ENTERTAINMENT experience... Wherever you’re going, whatever your mood, you’ll find over 2500 channels of the world’s best inflight entertainment to explore on today’s flight. THE LATEST Information… Communication… Entertainment… Track the progress of your Stay connected with in-seat* phone, Experience Emirates’ award- MOVIES flight, keep up with news SMS and email, plus Wi-Fi and mobile winning selection of movies, you can’t miss movies and other useful features. roaming on select flights. TV, music and games. from page 16 527 ...AT YOUR FINGERTIPS STAY CONNECTED 4 Connect to the 1500 OnAir Wi-Fi network on all A380s and most Boeing 777s 1 Choose a channel Go straight to your chosen programme by typing the channel WATCH LIVE TV 2 3 number into your handset, or use the onscreen channel entry pad Live news and sport channels are available on 1 3 Swipe left and Search for Move around most fl ights. Find out right like a tablet. movies, TV using the games more on page 9. Tap the arrows shows, music controller pad onscreen to and system on your handset scroll features and select using the green game 2 4 Create and Tap Settings to button 4 access your own adjust volume playlist using and brightness Favourites Home Again Many movies are 113 available in up to eight languages. -

Woyzeck Bursts Onto the Ensemble Theatre Company Stage

MEDIA RELEASE CONTACT: Josh Gren [email protected] or 805.965.5400 x103 ELECTRIFYING TOM WAITS MUSICAL WOYZECK BURSTS ONTO THE ENSEMBLE THEATRE COMPANY STAGE March 25, 2015 – Santa Barbara, CA — The influential 19th Century play about a soldier fighting to retain his humanity has been transformed into a tender and carnivalesque musical by the legendary vocalist, Tom Waits. “If there’s one thing you can say about mankind,” the show begins, “there’s nothing kind about man.” The haunting opening phrase is the heart of the thrilling, bold, and contemporary English adaptation of Woyzeck – the classic German play, being presented at Ensemble Theatre Company this April. Inspired by the true story of a German soldier who was driven mad by army medical experiments and infidelity, Georg Büchner’s dynamic and influential 1837 poetic play was left unfinished after the untimely death of its author. In 2000, Waits and his wife and collaborator, Kathleen Brennan, resurrected the piece, wrote music for an avant-garde production in Denmark, and the resulting work became a Woyzeck musical and an album entitled “Blood Money.” “[The music] is flesh and bone, earthbound,” says Waits. “The songs are rooted in reality: jealousy, rage…I like a beautiful song that tells you terrible things. We all like bad news out of a pretty mouth.” Woyzeck runs at the New Vic Theater from April 16 – May 3 and opens Saturday, April 18. Jonathan Fox, who has served as ETC’s Executive Artistic Director since 2006, will direct the ambitious, wild, and long-awaited musical. “It’s one of the most unusual productions we’ve undertaken,” says Fox. -

Translation Rights List Non-Fiction

TRANSLATION RIGHTS LIST NON-FICTION Frankfurt Book Fair 2016 General Non-Fiction……………………….……...........p.2 Business and Management……………………...……p.8 History……………………………………………………..p.10 Memoirs and Biography……………………………….p.15 Modern Life……………………………………………….p.20 Health, Self-help and Popular Psychology……….....p.21 Parenting…………………………………………………..p.27 Food and Cookery……..…………………….….………p.29 Overcoming Series………………………………………p.32 ANDY HINE Rights Director (for Brazil, Germany, Italy, Poland, Scandinavia, Latin America and the Baltic States) [email protected] KATE HIBBERT Rights Director (for the USA, Spain, Portugal, Far East and the Netherlands) [email protected] HELENA DOREE Senior Rights Manager (for France, Turkey, Arab States, Israel, Greece, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Slovak Republic, Hungary, Romania, Russia, Serbia and Macedonia) [email protected] JOE DOWLEY Rights Assistant [email protected] Little, Brown Book Group Ltd Carmelite House 50 Victoria Embankment London EC4Y 0DZ Tel: +44 020 3122 6209 email: [email protected] Rights sold displayed in parentheses indicates that we do not control the rights * Indicates new title since previous Rights list Titles in italics were not published by Little, Brown Book Group GENERAL NON-FICTION BREAKING DOWN THE WALLS OF HEARTACHE by Martin Aston Popular culture | 592pp | 16pp colour and b&w picture section | Constable | October 2016 | Korea: | Japan: EAJ The very first history of gay popular music Popular music’s gay DNA is inarguable, from Elvis in eye shadow and Little Richard’s ‘Tutti Frutti’ to The Velvet Underground’s subversive rock’n’roll and Bowie’s ambisexual alien Ziggy Stardust; from disco diva Sylvester and Frankie Says ‘Relax’ to Frankie Knuckles; from Boy George to Morrissey’s ‘fourth sex’; from k.d. -

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Disneylanders Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/18f2j3d1 Author Abbott, Kate Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Disneylanders A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing and Writing for the Performing Arts by Kate Elizabeth Abbott June 2012 Thesis Committee: Professor Elizabeth Crane Brandt, Co-Chairperson Professor Laila Lalami, Co-Chairperson Professor Mary Waters Copyright by Kate Elizabeth Abbott 2012 The Thesis of Kate Elizabeth Abbott is approved: _____________________________________________ _____________________________________________ Committee Co-Chairperson _____________________________________________ Committee Co-Chairperson University of California, Riverside Chapter 1: “Remain Seated, Please” — Matterhorn safety announcement Ow! I woke up when my forehead thudded against the window. Embarrassing, definitely, but as soon as I opened my eyes, I was too excited to be humiliated. Outside, rows of green crops flickered as we drove past — a boring view to some, but it made me want to bounce in my seat. It meant we were one-third of the way to Disneyland. “Are you okay back there, Casey?” My mom twisted around to see if I’d managed to smash my skull open while buckled into the backseat of a sedan. “I heard a clunk.” “Don’t worry, she’s got a hard head,” my dad said, clearly amusing himself. He said that every time my mom overreacted to a minor injury. “Maybe you ought to wear a helmet on the next trip, Acacia.” He glanced at me in the rearview mirror, and I pretended I was fixing my ponytail instead of rubbing my forehead.