Comic Art, Children's Literature, and the New Comics Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of American Comics Creators 1 List of American Comics Creators

List of American comics creators 1 List of American comics creators This is a list of American comics creators. Although comics have different formats, this list covers creators of comic books, graphic novels and comic strips, along with early innovators. The list presents authors with the United States as their country of origin, although they may have published or now be resident in other countries. For other countries, see List of comic creators. Comic strip creators • Adams, Scott, creator of Dilbert • Ahern, Gene, creator of Our Boarding House, Room and Board, The Squirrel Cage and The Nut Bros. • Andres, Charles, creator of CPU Wars • Berndt, Walter, creator of Smitty • Bishop, Wally, creator of Muggs and Skeeter • Byrnes, Gene, creator of Reg'lar Fellers • Caniff, Milton, creator of Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon • Capp, Al, creator of Li'l Abner • Crane, Roy, creator of Captain Easy and Wash Tubbs • Crespo, Jaime, creator of Life on the Edge of Hell • Davis, Jim, creator of Garfield • Defries, Graham Francis, co-creator of Queens Counsel • Fagan, Kevin, creator of Drabble • Falk, Lee, creator of The Phantom and Mandrake the Magician • Fincher, Charles, creator of The Illustrated Daily Scribble and Thadeus & Weez • Griffith, Bill, creator of Zippy • Groening, Matt, creator of Life in Hell • Guindon, Dick, creator of The Carp Chronicles and Guindon • Guisewite, Cathy, creator of Cathy • Hagy, Jessica, creator of Indexed • Hamlin, V. T., creator of Alley Oop • Herriman, George, creator of Krazy Kat • Hess, Sol, creator with -

Igncc18 Programme

www.internationalgraphicnovelandcomicsconference.com [email protected] #IGNCC18 @TheIGNCC RETRO! TIME, MEMORY, NOSTALGIA THE NINTH INTERNATIONAL GRAPHIC NOVEL AND COMICS CONFERENCE WEDNESDAY 27TH – FRIDAY 29TH JUNE 2018 BOURNEMOUTH UNIVERSITY, UK Retro – a looking to the past – is everywhere in contemporary culture. Cultural critics like Jameson argue that retro and nostalgia are symptoms of postmodernism – that we can pick and choose various items and cultural phenomena from different eras and place them together in a pastiche that means little and decontextualizes their historicity. However, as Bergson argues in Memory and Matter, the senses evoke memories, and popular culture artefacts like comics can bring the past to life in many ways. The smell and feel of old paper can trigger memories just as easily as revisiting an old haunt or hearing a piece of music from one’s youth. As fans and academics we often look to the past to tell us about the present. We may argue about the supposed ‘golden age’ of comics. Our collecting habits may even define our lifestyles and who we are. But nostalgia has its dark side and some regard this continuous looking to the past as a negative emotion in which we aim to restore a lost adolescence. In Mediated Nostalgia, Ryan Lizardi argues that the contemporary media fosters narcissistic nostalgia ‘to develop individualized pasts that are defined by idealized versions of beloved lost media texts’ (2). This argument suggests that fans are media dupes lost in a reverie of nostalgic melancholia; but is belied by the diverse responses of fandom to media texts. Moreover, ‘retro’ can be taken to imply an ironic appropriation. -

Writing About Comics

NACAE National Association of Comics Art Educators English 100-v: Writing about Comics From the wild assertions of Unbreakable and the sudden popularity of films adapted from comics (not just Spider-Man or Daredevil, but Ghost World and From Hell), to the abrupt appearance of Dan Clowes and Art Spiegelman all over The New Yorker, interesting claims are now being made about the value of comics and comic books. Are they the visible articulation of some unconscious knowledge or desire -- No, probably not. Are they the new literature of the twenty-first century -- Possibly, possibly... This course offers a reading survey of the best comics of the past twenty years (sometimes called “graphic novels”), and supplies the skills for reading comics critically in terms not only of what they say (which is easy) but of how they say it (which takes some thinking). More importantly than the fact that comics will be touching off all of our conversations, however, this is a course in writing critically: in building an argument, in gathering and organizing literary evidence, and in capturing and retaining the reader's interest (and your own). Don't assume this will be easy, just because we're reading comics. We'll be working hard this semester, doing a lot of reading and plenty of writing. The good news is that it should all be interesting. The texts are all really good books, though you may find you don't like them all equally well. The essays, too, will be guided by your own interest in the texts, and by the end of the course you'll be exploring the unmapped territory of literary comics on your own, following your own nose. -

The Atrocity Exhibition

The Atrocity Exhibition WITH AUTHOR'S ANNOTATIONS PUBLISHERS/EDITORS V. Vale and Andrea Juno BOOK DESIGN Andrea Juno PRODUCTION & PROOFREADING Elizabeth Amon, Laura Anders, Elizabeth Borowski, Curt Gardner, Mason Jones, Christine Sulewski CONSULTANT: Ken Werner Revised, expanded, annotated, illustrated edition. Copyright © 1990 by J. G. Ballard. Design and introduction copyright © 1990 by Re/Search Publications. Paperback: ISBN 0-940642-18-2 Limited edition of 300 autographed hardbacks: ISBN 0-940642-19-0 BOOKSTORE DISTRIBUTION: Consortium, 1045 Westgate Drive, Suite 90, Saint Paul, MN 55114-1065. TOLL FREE: 1-800-283-3572. TEL: 612-221-9035. FAX: 612-221-0124 NON-BOOKSTORE DISTRIBUTION: Last Gasp, 777 Florida Street, San Francisco, CA 94110. TEL: 415-824-6636. FAX: 415-824-1836 U.K. DISTRIBUTION: Airlift, 26 Eden Grove, London N7 8EL TEL: 071-607-5792. FAX: 071-607-6714 LETTERS, ORDERS & CATALOG REQUESTS TO: RE/SEARCH PUBLICATIONS SEND SASE 20ROMOLOST#B FOR SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94133 CATALOG PH (415) 362-1465 FAX (415) 362-0742 REQUESTS Printed in Hong Kong by Colorcraft Ltd. 10987654 Front Cover and all illustrations by Phoebe Gloeckner Back Cover and all photographs by Ana Barrado Endpapers: "Mucous and serous acini, sublingual gland" by Phoebe Gloeckner Phoebe Gloeckner (M.A. Biomedical Communication, Univ. Texas) is an award-winning medical illustrator whose work has been published internationally. She has also won awards for her independent films and comic art, and edited the most recent issue of Wimmin's Comix published by Last Gasp. Currently she resides in the San Francisco Bay Area. Ana Barrado is a photographer whose work has been exhibited in Italy, Mexico City, Japan the United States. -

Dan Dare the 2000 Ad Years Vol. 01 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

DAN DARE THE 2000 AD YEARS VOL. 01 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Pat Mills | 320 pages | 05 Nov 2015 | Rebellion | 9781781083499 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom Dan Dare The 2000 AD Years Vol. 01 PDF Book I guess I'd agree with some of the comments about the more recent revival attempts and the rather gauche cynicism that tends to pervade them. Thanks for sharing that, it's a good read. The pen is mightier than the sword if the sword is very short, and the pen is very sharp. The cast included Mick Ford Col. John Constantine is dying. There are no discussion topics on this book yet. Hardcover , pages. See all 3 brand new listings. Al rated it really liked it Feb 06, Archived from the original PDF on The stories were set mostly on planets of the Solar System presumed to have extraterrestrial life and alien inhabitants, common in science fiction before space probes of the s proved the most likely worlds were lifeless. Mark has been an executive producer on all his movies, and for four years worked as creative consultant to Fox Read full description. Standard bred - ; vol. The first Dan Dare story began with a starving Earth and failed attempts to reach Venus , where it is hoped food may be found. You may also like. Ian Kennedy Artist. Pages: [ 1 ] 2. SuperFanboyMan rated it really liked it Jul 16, In Eagle was re-launched, with Dan Dare again its flagship strip. John Wiley and Sons, Author : Michigan State University. In a series of episodic adventures, Dare encountered various threats, including an extended multi-episode adventure uniting slave races in opposition to the "Star Slayers" — the oppressive race controlling that region. -

Anaheim Convention Center & Hilton Anaheim Maps

Quick Guide Everything you need to know about WonderCon Anaheim 2019 Anaheim Convention Center & Hilton Anaheim Maps Exhibit Hall Map and Exhibitor Lists Artists’ Alley Exhibitors Fan Groups Small Press Future Tech Live! Complete Program Schedule Grids FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY TM & © DC Comics Anaheim Convention Center Maps Anaheim Convention Center Maps Anaheim Convention center LEVEL 3 MAPS LOCATION ANAHEIM CONVENTION CENTER LEVEL 1 ANAHEIM CONVENTION CENTER LEVEL 3 Hall D Hall C Hall B Hall A Lobby Stroller Parking NEW FOR 2019: M W Hall E is located one WEST KATELLA AVENUE WEST KATELLA level below Hall D. 300D Lines 300B Please use escalators/ EXHIBIT HALL: 303AB elevators in Lobby C/D Halls A, B and C ARENA Children’s Hall A: Film Fest. to access Hall E Arena Lines Programming LOCATION MAPS LOCATION Pedestrian Bridge (Second Level) ELEVATORS Lobby B/C ELEVATORS ESCALATORS ELEVATORS GRAND PLAZA ESCALATORS ESCALATORS ELEVATORS ACC North Costume Props Plaza RFID Tent Check Desk Programming HALL E (LOCATED BELOW HALL D) LOBBY B/C Badge Pick-up — Bag Check Attendees, Press, Professionals Blood Drive Sign-up ANAHEIM CONVENTION CENTER North level 100 and level 200 Bag, Lanyard, Program Book Pick-up Costume Props Check Desk Badge and RFID Help Desk Deaf & Disabled Services Costume Props Check Desk and ASL Interpreters ACC North Level 100 ACC North Level 200 Morning Lines Masquerade Desk WonderCon Anaheim Information Desk M W ANAHEIM CONVENTION CENTER LEVEL 2 Anaheim Convention center – LEVEL 2 M W M W M W 206B 204C M W 213CD 209 -

SFRA Newsletter

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications 4-1-2008 SFRA ewN sletter 284 Science Fiction Research Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub Part of the Fiction Commons Scholar Commons Citation Science Fiction Research Association, "SFRA eN wsletter 284 " (2008). Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications. Paper 98. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub/98 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. • Spring 2008 Editors I Karen Hellekson 16 Rolling Rdg. Jay, ME 04239 [email protected] [email protected] SFRA Review Business SFRA Review Institutes New Feature 2 Craig Jacobsen English Department SFRA Business Mesa Community College SFRA in Transition 2 1833 West Southern Ave. SFRA Executive Board Meeting 2 Mesa, AZ 85202 2008 Program Committee Update 3 [email protected] 2008 Clareson Award 3 [email protected] 2008 Pilgrim Award 4 2008 Pioneer Award 4 Feature Article: 101 Managing Editor Comics Studies 101 4 Janice M. Bogstad Feature Article: One Course McIntyre Library-CD PKD Lit and Film 7 University ofWisconsin-Eau Claire 105 Garfield -

Sigil NPC List by Ambrus.Xlsx

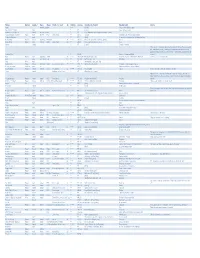

Name Nature Gender Race Class Faction / Sect AL Rating Source Commonly Found Background Quote Abaia tanar'ri, bebilith *** [Guild] Infected with Ybdiel's spark Able Ponder-Thought male * PT [Clerk] Sage (Lady's mazes) Acaste the Ghoul-Queen female skeletal undead * PT Dead Nations beneath Ragpicker's Square [Under] Acorrid Degasias (juvenile) Planar male half-elf NPC? Free League N ** DG-15 [Lower] Had beauty stolen by khaasta raiders Adahn the Imagined male ** PT [Hive] Imagined into existance by the Nameless One Adamok Ebon Planar female bladeling Ftr6/Clr5 LE ***** UFS-28 Fat Candle pub, Feathernest Inn [Guild] Hunter Addle-Pated Planar male tiefling NPC? Bleak Cabal CG *** FM-29 Cold Bowl Soup Kitchen [Hive] Cook Aelwyn female * PT [Clerk] Friend of Nemelle "The Lady is no Xaositect, blown by the winds of whimsy. Her every action is measured and precise, occuring at a particular moment in time for a particular reason, a link in a cosmic chain of events that we cannot–or will Aisal gor'Dan * FW-94 Author of Cause and Effect not-see." A'kin Planar male yugoloth, ar12HD NE ***** UFS-8; HH-1 Friendly Fiend [Lady] Proprietor, Author of The Factol's Manifesto "Come in, come in! I won't bite." Akra male cyclops, less5HD CE ** ITC-109 Bottle & Jug [Hive] Pit Fighter Alais Prime male * PT Smoldering Corpse Bar [Hive] Aleena Jerkot Planar female githzerai Rog7 Society of Sensation NE **** DTU-13 Jerkot's Imports [Clerk] Proprietor, thief, smuggler, fence Aleron (deceased) Petitioner male elf * SW-11 Visitor from Arborea, friend of Minda Alisohn Nilesia Planar female tiefling Wiz8 Mercykillers LE ***** FM-102 Prison [Lady] Factol “I know I'm right. -

Free Comic Book Day 2017 Checklist

Free Comic Book Day May 6th, 2017 Comics Checklist DC SUPER HERO GIRLS (Shea Fontana, Yancy Labat, DC Comics) Gold Comics COLORFUL MONSTERS BETTY & VERONICA #1 (Anouk Ricard, Elise Gravel, Drawn & Quarterly) (Adam Hughes, Archie Comics) HOSTAGE BONGO COMICS FREE-FOR-ALL (Guy Delisle, Brigitte Findakly Drawn & Quarterly) (Matt Groening, Bongo Comics) ANIMAL JAM BOOM! STUDIOS SUMMER BLAST (Fernando Ruiz, Pete Pantazis, D.E.) (David Petersen, Kyla Vanderklugt, Boom! Studios) TEX PATAGONIA BRIGGS LAND/JAMES CAMERON’S AVATAR (Mauro Boselli, Pasquale Frisenda, D.E.) (Sherri Smith, Brian Wood, Doug Wheatley, Werther Dell’Edera, Dark WORLD’S GREATEST CARTOONISTS Horse Comics) (Noah Van Sciver, Fantagraphics) WONDER WOMAN SPILL NIGHT (Greg Rucka, Nicola Scott, DC Comics) (Scott Westerfeld, Alex Puvilland, :01 First Second) STAR TREK: THE NEXT GENERATION: MIRROR BROKEN GRAPHIX SPOTLIGHT: TIME SHIFTERS (Scott Tipton, David Tipton, J. K. Woodward, IDW) (Chris Grine, Graphix) I HATE IMAGE THE INCAL (Skottie Young, Image Comics) (Alejandro Jodorowsky, Moebius, U-Jin, Humanoids Inc.) SECRET EMPIRE TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA TURTLES: PRELUDE TO (Nick Spencer, Andrea Sorrentino, Marvel Comics) DIMENSION X RICK & MORTY (Tom Waltz, Cory Smith, IDW) (Zac Gorman, Tini Howard, CJ Cannon, Maximus Pauson, Oni Press) KID SAVAGE DOCTOR WHO (Joe Kelly, Ilya, Image Comics) (Alex Paknadel, Mariano Laclaustra, Titan Comics) ATTACK ON TITAN X-O MANOWAR SPECIAL (Jody Houser, Emi Lenox, Paolo Rivera, Kodansha Comics) (Matt Kindt, Jeff Lemire (A) Tomas -

PDF (Author Accepted Manuscript)

Article The Other Narratives of Sexual Violence in Phoebe Gloeckner’s A Child’s Life and Other Stories Michael, Olga Available at http://clok.uclan.ac.uk/21566/ Michael, Olga ORCID: 0000-0003-0523-9929 (2018) The Other Narratives of Sexual Violence in Phoebe Gloeckner’s A Child’s Life and Other Stories. Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics, 9 (3). pp. 229-250. ISSN 2150-4857 It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21504857.2018.1462223 For more information about UCLan’s research in this area go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/researchgroups/ and search for <name of research Group>. For information about Research generally at UCLan please go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/research/ All outputs in CLoK are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including Copyright law. Copyright, IPR and Moral Rights for the works on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the policies page. CLoK Central Lancashire online Knowledge www.clok.uclan.ac.uk The Other Narratives of Sexual Violence in Phoebe Gloeckner’s A Child’s Life and Other Stories Introduction Phoebe Gloeckner’s A Child’s Life and Other Stories (2000) primarily narrates, through obscene and discomforting depictions, Minnie’s semi-incestuous sexual violation during childhood and adolescence by two of her mother’s boyfriends. In this essay, I examine parallel narratives of sexual violence, identified through an intertextual approach that considers Gloeckner’s art-historical and literary influences. -

Guidelines for the Conservation of Lions in Africa

Guidelines for the Conservation of Lions in Africa Version 1.0 – December 2018 A collection of concepts, best practice experiences and recommendations, compiled by the IUCN SSC Cat Specialist Group on behalf of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) and the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS) Guidelines for the Conservation of Lions in Africa A collection of concepts, best practice experiences and recommendations, compiled by the IUCN SSC Cat Specialist Group on behalf of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) and the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS) The designation of geographical entities in this document, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN or the organisations of the authors and editors of the document concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimi- tation of its frontiers or boundaries. 02 Frontispiece © Patrick Meier: Male lion in Kwando Lagoon, Botswana, March 2013. Suggested citation: IUCN SSC Cat Specialist Group. 2018. Guidelines for the Conservation of Lions in Africa. Version 1.0. Muri/Bern, Switzerland, 147 pages. Guidelines for the Conservation of Lions in Africa Contents Contents Acknowledgements..........................................................................................................................................................4 -

Portland Daily Press: December 07,1868

Portland daily press. DECEMBER 1868. Terms $8.00 per annum, in Established June 23,1862. Tol. 7. PORTLAND, MONDAY MORNING, 7, advance. MISCELLANEOUS. INSURANCE. INSURANCE. family, children and professors THE PORTLAND DA1L? PRESS Is published MISCELLANEOUS. of schools every day, (Sunday excepted,) at No. 1 Printer** daily founded and supported by him, the Exchange, Exchange Street, Portland. press. carriage EASE AND COMFORT! of the late Baron, and those of the N. A. FOSTER, Proprietor. family, A8BLRY WORLD POni'LAND. and then members of the central Terms:—Eight Dollars a year in advance. by I&raelit- fcy Single copies 4 cents. ish consistory. The grand Rabbi and his were at THE STATE Mutual Life Ins. December clergy the cemetery to receive the MAINE PRESS, is published at the REMOVAL!” Life Insurance Co., Monday Morning, 7. 1868. •ano place every Thursday morning at $2.50 a year; Comp’y body. If paid in advance $2.00 a year. 160 Neiv York. '1 ue great bankers death has Into -—--- Broadway, Tbo Case of Hester Vaughn. brought OFFICE 291 BROADWAY, Rates of Advertising.—One inch of in conspicuous notice some of the Israe itish space, that an length oi column, constitutes a “square.” Tlie Blessing oi Perfect Bight! We observe with some surprise of. Features. funeral obsci vances. is one $1.50 per first week. 75 cents Special There that peo- square daily per There is so as New-Yorlc, fort is made on tbe of certain joui- or notliiug valuable Perfect Sight, being part ple week after; three insertions, less, $1.00; contmu- have found quite touching.