Charcoal Analysis of the First Middle Neolithic Village Identified in Provence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Critical Review of “The Mesolithic” in Relation to Siberian Archaeology ALEXANDER B

ARCTIC VOL. 38, NO. 3 (SEPTEMBER 1985) P. 178-187 A Critical Review of “the Mesolithic” in Relation to Siberian Archaeology ALEXANDER B. DOLITSKY’ ABSTRACT. This paperexplores the potentialof the economic-ecqlogical method basedon the exploitation of fishresources for Mesolithic site iden- tification, as compared to the recently popular yet indecisive technological-typologicalmethod, to predict the existence of “Mesolithic-like” sub- sistence activities in Siberia during the Sartan-Holocene“transition” period. The article is an attempt toestablish, or at least topropose, new criteria that can lead toa higher level of understandingof Mesolithic economies insubarctic and arctic regions. Also, decision-making processes that operate to achieve behavioralgoals based on efficiency of human beingsare suggested. The model, designed with respectto geographical regions identified as interbiotic zones, has the advantage of offering specific alternative hypotheses enabling the definition of both environmental properties and predicted human behavior. Key words: Mesolithic, Siberia, interbiotic zone RÉSUMÉ. L’article &die le potentiel de la méthode économique-écologique fondte sur l’exploitation de poissons en guise de ressources pour l’identification desites mtsolithiques, en comparison avecla mdthode technologique-typologique populaire maisindécise, afin de prddire l’existence d’activitds de subsistencede genre mésolithique en Sibdrie durant la périodede transition Sartan-Holoctne. On tente d’établir ou au moins de pro- poser de nouveaux crittres qui pourraient permettre une meilleure comprdhension des économies mdsolithiques dans les rdgions arctiques et sub- arctiques. De plus, on suggkre des processus de prise de ddcisions qui visent21 établir des buts de comportement fondéssur l’efficacité de I’être hu- main.Conçu par rapport 21 des rdgionsgéographiques nommées zones interbiotiques, le modele a l’avantage d’offrir des choix particuliers d’hypothtses permettant la ddfinition des propridtés environnementales et du comportement humain prévu. -

Riparo Arma Di Nasino Series

University of Rome Carbon-14 Dates VI Item Type Article; text Authors Alessio, M.; Bella, F.; Cortesi, C.; Graziadei, B. Citation Alessio, M., Bella, F., Cortesi, C., & Graziadei, B. (1968). University of Rome carbon-14 dates VI. Radiocarbon, 10(2), 350-364. DOI 10.1017/S003382220001095X Publisher American Journal of Science Journal Radiocarbon Rights Copyright © The American Journal of Science Download date 06/10/2021 12:06:07 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Version Final published version Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/651722 [RADIOCARBON, VOL. 10, No. 2, 1968, P. 350-364] UNIVERSITY OF ROME CARBON-14 DATES VI M. ALESSIO, F. BELLA Istituto di Fisica, University di Roma Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare, Sezione di Roma C. CORTESI and B. GRAZIADEI Istituto di Geochimica, University di Roma The list includes age measurements carried out from December 1966 and November 1967. All samples both of archaeologic and geologic in- terest are drawn from Italian territory. Chemical techniques have remained unchanged (Bella and Cortesi, 1960). Two counters have been used for dating: the 1st, of 1.5 L, already described (Bella and Cortesi, 1960; Alessio, Bella, and Cortesi, 1964), the 2nd, of 1 L, recently assembled, is identical to the previous 1 L counter (Alessio, Bella, and Cortesi, 1964), its anticoincidence system was realized by a plastic scintillator and photomultipliers. Background 6.15 + 0.08 counts/min, counting rate for modern carbon 24.49 + 0.15 counts/min. Higher efficiency of electronic recording was obtained by reducing pulse length and by a few other changes. -

Hunters and Farmers in the North – the Transformation of Pottery Traditions

Hunters and farmers in the North – the transformation of pottery traditions and distribution patterns of key artefacts during the Mesolithic and Neolithic transition in southern Scandinavia Lasse Sørensen Abstract There are two distinct ceramic traditions in the Mesolithic (pointed based vessels) and Neolithic (flat based vessels) of southern Scandinavia. Comparisons between the two ceramic traditions document differences in manufacturing techniques, cooking traditions and usage in rituals. The pointed based vessels belong to a hunter-gatherer pottery tradition, which arrived in the Ertebølle culture around 4800 calBC and disappears around 4000 calBC. The flat based vessels are known as Funnel Beakers and belong to the Tragtbæger (TRB) culture, appearing around 4000 calBC together with a new material culture, depositional practices and agrarian subsistence. Pioneering farmers brought these new trends through a leap- frog migration associated with the Michelsberg culture in Central Europe. These arriving farmers interacted with the indigenous population in southern Scandinavia, resulting in a swift transition. Regional boundaries observed in material culture disappeared at the end of the Ertebølle, followed by uniformity during the earliest stages of the Early Neolithic. The same boundaries reappeared again during the later stages of the Early Neolithic, thus supporting the indigenous population’s important role in the neolithisation process. Zusammenfassung Keywords: Southern Scandinavia, Neolithisation, Late Ertebølle Culture, Early -

8. Flint Cobe Axe Found on Fair Isle, Shetland

8. FLINT COBE AXE FOUND ON FAIR ISLE, SHETLAND. The purpose of this note is to put on record the discovery of what seems to b Mesolithiea c flin Fain to corre Isleeax , Shetland discovere Th . mads ywa e in June 1945 while the writer, accompanied by Sub-Lieutenant Appleby, R.N., then in charge of the naval station on the island, was searching for skua chicks. NOTES. 147 The s embeddeflinwa t d with other pebble patca n si f bar ho e ground from which the peat had been eroded. The site was the summit of a knoll on the edge plateae oth f u wher Greae eth t Skua nests aboud yard0 an , 80 t s west-north-west of the naval huts at North Haven. I estimated the height above sea-level as about 300 feet. It is a matter of regret that I did not think of preserving any of the peaty soil in which the flint was embedded on the chance that it might have contained the pollen that would have helped to locate the object in terms of the North European climatic sequence. When this was pointed out to me by Professor Childen touci t n effors mada hge , wa wito tt e h Sub-Lieutenant Applebo t y procure some of the soil, but he was no longer on the island, and no other opportunity has arisen of revisiting the island. objece e ende flina th Th f s Th i sto t cor. measurine 4-y b 5eax cm . cm 2 g1 t notablno flins beee ar ha yt n t shari give t pbu n sharp edgesedgee e Th ar s. -

Respiratory Adaptation to Climate in Modern Humans and Upper Palaeolithic Individuals from Sungir and Mladeč Ekaterina Stansfeld1*, Philipp Mitteroecker1, Sergey Y

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Respiratory adaptation to climate in modern humans and Upper Palaeolithic individuals from Sungir and Mladeč Ekaterina Stansfeld1*, Philipp Mitteroecker1, Sergey Y. Vasilyev2, Sergey Vasilyev3 & Lauren N. Butaric4 As our human ancestors migrated into Eurasia, they faced a considerably harsher climate, but the extent to which human cranial morphology has adapted to this climate is still debated. In particular, it remains unclear when such facial adaptations arose in human populations. Here, we explore climate-associated features of face shape in a worldwide modern human sample using 3D geometric morphometrics and a novel application of reduced rank regression. Based on these data, we assess climate adaptations in two crucial Upper Palaeolithic human fossils, Sungir and Mladeč, associated with a boreal-to-temperate climate. We found several aspects of facial shape, especially the relative dimensions of the external nose, internal nose and maxillary sinuses, that are strongly associated with temperature and humidity, even after accounting for autocorrelation due to geographical proximity of populations. For these features, both fossils revealed adaptations to a dry environment, with Sungir being strongly associated with cold temperatures and Mladeč with warm-to-hot temperatures. These results suggest relatively quick adaptative rates of facial morphology in Upper Palaeolithic Europe. Te presence and the nature of climate adaptation in modern humans is a highly debated question, and not much is known about the speed with which these adaptations emerge. Previous studies demonstrated that the facial morphology of recent modern human groups has likely been infuenced by adaptation to cold and dry climates1–9. Although the age and rate of such adaptations have not been assessed, several lines of evidence indicate that early modern humans faced variable and sometimes harsh environments of the Marine Isotope Stage 3 (MIS3) as they settled in Europe 40,000 years BC 10. -

Cover SD Tagungen4 Gronen

Sonderdruck aus / Offprint from Die Neolithisierung Mitteleuropas The Spread of the Neolithic to Central Europe Die Tagung wurde gefördert durch: RGZM – TAGUNGEN Band 4 ISBN 978-3-88467-159-7 ISNN 1862-4812 © 2010 Verlag des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums Mainz € 78,– Bestellungen / orders: shop.rgzm.de [email protected] Satz: Andrea Fleckenstein, Frankfurt; Claudia Nickel (RGZM) Gesamtredaktion: Stefanie Wefers (RGZM) Endredaktion: Stefanie Wefers, Claudia Nickel (RGZM) Umschlagbild: Michael Ober (RGZM) Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Das Werk ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Die dadurch begründe- ten Rechte, insbesondere die der Übersetzung, des Nachdrucks, der Entnahme von Abbildungen, der Funk- und Fernsehsendung, der Wiedergabe auf fotomechanischem (Fotokopie, Mikrokopie) oder ähnlichem Wege und der Speicherung in Datenverarbei- tungsanlagen, Ton- und Bildträgern bleiben, auch bei nur aus- zugsweiser Verwertung, vorbehalten. Die Vergütungsansprüche des §54, Abs. 2, UrhG. werden durch die Verwertungsgesell- schaft Wort wahrgenommen. Herstellung: Druck- und Verlagsservice Volz, Budenheim Printed in Germany Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum Forschungsinstitut für Vor- und Frühgeschichte Detlef Gronenborn · Jörg Petrasch (Hrsg.) DIE NEOLITHISIERUNG MITTELEUROPAS Internationale Tagung, Mainz 24. bis 26. Juni 2005 THE SPREAD -

Pleistocene - the Ice Ages

Pleistocene - the Ice Ages Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore Pleistocene - the Ice Ages • Stage is now set to understand the nature of flora and vegetation of North America and Great Lakes • Pliocene (end of Tertiary) - most genera had already originated (in palynofloras) • Flora was in place • Vegetation units (biomes) already derived Pleistocene - the Ice Ages • In the Pleistocene, earth experienced intensification towards climatic cooling • Culminated with a series of glacial- interglacial cycles • North American flora and vegetation profoundly influenced by these “ice-age” events Pleistocene - the Ice Ages What happened in the Pleistocene? 18K ya • Holocene (Recent) - the present interglacial started ~10,000 ya • Wisconsin - the last glacial (Würm in Europe) occurred between 115,000 ya - 10,000 ya • Height of Wisconsin glacial activity (most intense) was 18,000 ya - most intense towards the end of the glacial period Pleistocene - the Ice Ages What happened in the Pleistocene? • up to 100 meter drop in sea level worldwide • coastal plains become extensive • continental islands disappeared and land bridges exposed 100 m line Beringia Pleistocene - the Ice Ages What happened in the Pleistocene? • up to 100 meter drop in sea level worldwide • coastal plains become extensive • continental islands disappeared and land bridges exposed Malaysia to Asia & New Guinea and New Caledonia to Australia Present Level 100 m Level Pleistocene - the Ice Ages What happened in the Pleistocene? • up to 100 meter drop in sea level worldwide • coastal -

New Studies of the Upper Paleolithic Site Byki-7 on the Seim River

New studies of the Upper Paleolithic site Byki-7 on the Seim River Group of the Upper Paleolithic sites of Byki are situated on the left bank of Seim River (Desna river basin) 470 km SSW from Moscow and 50 km to the East from Kursk (Grigorieva & Filippov 1978; Chubur 2001; Akhmetgaleeva 2015). The main typological feature of Peny, Byki 1, 2, 3 and 7 (layers Ia & I) sites’ flint assemblages is the presence of geometric microliths, mainly triangles with oblique truncation of one edge and a straight truncated base. Complexes belong to the Late Upper Paleolithic with rich archaeological and faunal context. The close similarity of the sites’ points assemblage let us say about their archaeological unity. The lower cultural layers suspected as the remains of winter time settlements. We did not find yet any really archaeologically comparable materials for the Byki site’s data outside this micro region. Fig. 1. Spatial distribution of different cultural layers and dwellings on the Byki-7 site. 1 - boundaries of the cultural layer Ia; 2 - boundaries of the cultural layer I: 1, 2 –numbering of Layer I dwellings; 3 - boundaries of the cultural layer II; 4 - areas of maximum saturation of the cultural layer Ia; 5 - boundaries of permafrost deformations of II generation; 6 - boundaries of permafrost deformations of I generation; 7 - the location of cultural layer Ib. The analysis of Byki fauna materials has definitely showed the presence of a boreal sub-complex of so-called Late Last Glacial mammoth faunal complex (Akhmetgaleeva & Burova 2008). Basic hunting animals for human inhabitants of Byki sites were hare, arctic fox, reindeer and horse (Equus ferus). -

A Reexamination of Late-Pleistocene Boreal Forest Reconstructions for the Southern High Plains

QUATERNARY RESEARCH 28,238-244 (1987) A Reexamination of Late-Pleistocene Boreal Forest Reconstructions for the Southern High Plains VANCE T. HOLLIDAY Department of Geography, Science Hall, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin 53706 Received March 9, 1987 Previous paleoecological research on the Southern High Plains resulted in development of a late Quatemary chronology of “pollen-analytical episodes” and the proposal that boreal forest existed in the region in the late Pleistocene. These interpretations are now considered untenable because (1) a number of the radiocarbon ages are questionable, (2) there are serious problems of differential pollen preservation and reproducibility of the pollen data, (3) there is an absence of supporting geological or paleontological data, and (4) the soils of the area contain none of the distinctive pedologicd characteristics produced by a boreal forest. Available data suggest that the region was primarily an open grassland or grassland with some nonconiferous trees through most of the Qua- ternary. 0 1987 University of Washington. INTRODUCTION leoecological data were collected and most of the interpretations made. This paper is a In the late 1950s and early 1960s consid- critical reexamination of the chronology of erable research was conducted into the late the proposed pollen-analytical episodes Quaternary, principally late Pleistocene, and the interpretations of boreal forest for paleoecology of the Southern High Plains the region, made in light of recent advances of northwestern Texas and eastern New in palynology and radiocarbon dating and Mexico (Wendorf, 1961a; Wendorf and better understanding of the late Quaternary Hester, 1975a). One of the most significant geology, soils, and paleontology of the discoveries made, b,ased on considerable Southern High Plains and following on pollen data, was the high content of pine some points raised by Holliday er al. -

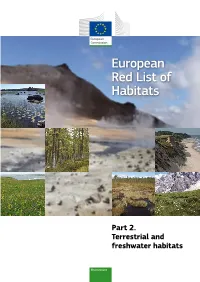

European Red List of Habitats

European Red List of Habitats Part 2. Terrestrial and freshwater habitats Environment More information on the European Union is available on the internet (http://europa.eu). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2016 ISBN 978-92-79-61588-7 doi: 10.2779/091372 © European Union, 2016 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. The photos are copyrighted and cannot be used without prior approval from the photographers. Printed in England Printed on recycled paper that has been awarded the EU eco-label for graphic paper (http://ec.europa.eu/environment/ecolabel/) Cover: Active volcano, Iceland. © Wim Ozinga. Insets: Freshwater lake, Finland. © Heikki Toivonen. Larix forest, Mercantour, France. © Benoît Renaux. Soft coastal cliff, Latvia. © John Janssen. Machair grassland, Ireland. © Joop Schaminée. Calcareous quaking mire, Finland. © Teemu Tahvanainen. Spring mire, Dolomites, Italy. © Michal Hájek. European Red List of Habitats Part 2. Terrestrial and freshwater habitats Authors J.A.M. Janssen, J.S. Rodwell, M. García Criado, S. Gubbay, T. Haynes, A. Nieto, N. Sanders, F. Landucci, J. Loidi, A. Ssymank, T. Tahvanainen, M. Valderrabano, A. Acosta, M. Aronsson, G. Arts, F. Attorre, E. Bergmeier, R.-J. Bijlsma, F. Bioret, C. Biţă-Nicolae, I. Biurrun, M. Calix, J. Capelo, A. Čarni, M. Chytrý, J. Dengler, P. Dimopoulos, F. Essl, H. Gardfjell, D. Gigante, G. Giusso del Galdo, M. Hájek, F. Jansen, J. Jansen, J. Kapfer, A. Mickolajczak, J.A. Molina, Z. Molnár, D. Paternoster, A. Piernik, B. Poulin, B. Renaux, J.H.J. Schaminée, K. Šumberová, H. Toivonen, T. Tonteri, I. Tsiripidis, R. Tzonev and M. Valachovič With contributions from P.A. -

Prehistory of the Northwest Coast ROY L

CHAPTER 1 Prehistory of the Northwest Coast ROY L. CARLSON n the beginning there was ice ... in the end there were ice. Sub-arctic and then temperate fauna spread into this approximately 100,000 Indian people living along the new found land. Man was part of this fauna; he preyed IPacific coast from southeast Alaska to the mouth of on the other animals for food and used their hides for the Columbia River in Oregon ... in between is the pre clothing. He arrived by different routes, and brought historic period, the time span of the unknown, between with him different cultural traditions. By 10,000 years the retreat of the last continental glacier and the arrival ago ice only existed in the mountain top remnants we of the first Europeans with their notebooks and artist's still see today. sketches who ushered in the period of written history. The Northwest Coast (Fig. 1:1) is a ribbon of green, The prehistoric period here lasted from perhaps 12,000 wet forested land which hugs the Pacific coast of North years ago to the late 1700's when Cook, Vancouver, America from the mouth of the Copper River in Alaska Mackenzie and others began writing about the area and to just below the mouth of the Klamath River in northwest its inhabitants. Glacial geology suggests that the coast California. It was part of the "Salmon Area" of early was ice free by 12,000 years ago, but there remains the ethnographers and its cultures were clearly different possibility of even earlier movements of peoples whose from those of the California acorn area, the agricultural traces were wiped out by the last glacial advance. -

Stone Adzes Or Antler Wedges

STONE ADZES OR ANTLER WEDGES ? AN EXPERIMENTAL STUDY ON PREHISTORIC TREE -FELLING IN THE NORTHWESTERN BOREAL REGION Jacques Cinq-Mars Department of Anthropology, 13-15 HM Tory Building, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada T6G 2R3; [email protected] or [email protected] Raymond Le Blanc Department of Anthropology, University of Alberta; [email protected] ABSTRACT “Adze-cut stumps” is the name commonly used by both local residents and passing ethnographers and archaeologists to designate culturally modified tree stumps that are known to occur in many areas of the Northwestern boreal forest. As the name implies, they have been viewed as indicative of ancient logging or tree-felling activities, presumably carried out with stone adzes, and whose resulting particu- lar morphological attributes have long been interpreted as indicative of a relatively great antiquity, i.e., generally dating back to (or prior to) the period of European contact when traded steel axes quickly replaced the stone adzes. However, a close examination of available ethnographic data, personal field observations, and, particularly, the first results of an experimental tree-felling study indicate quite convincingly that such features should best be interpreted as having been created by an entirely dif- ferent technique making use of “antler wedges.” Furthermore, field observations from the Old Crow/ Porcupine area can be used to suggest that quite a number of these “stumps,” especially when found in clusters, may well be associated with the construction and maintenance of caribou fences, semisubter- ranean housepits, and various types of caches. Finally, recently obtained preliminary dendrochrono- logical results and radiocarbon dates indicate that these “stumps” are indeed precontact in age, and that some of them date back to at least the beginning of the second millennium ad.