Temple Mount

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Where Did Solomon Build the Temple? by Dr

Post Office Box 345, San Antonio, Texas 78292-0345 Kislev –Tevet– Shevat–Adar 5777 / December– January– February 2016–2017 A Publication of CJF Ministries and Messianic Perspectives Radio Network MessianicPerspectives ® God has not forgotten the Jewish people, and neither have we. e are living in tumultuous times. Many things that Historical Background Wwe’ve always taken for granted are being called into question. The people of Israel had three central places of worship in ancient times: the Tabernacle, the First Temple, and the One hotly-disputed question these days is, “Were the an- Second Temple. Around 538 BC, the Jewish captives were cient Temples really on the Temple Mount?” You’d think released by King Cyrus of Persia to return from exile to the fact that Mount Moriah (and the manmade plat- their Land. Zerubbabel and Joshua the priest led the ef- form around it) has been known for many centuries as fort to rebuild the Second Temple, and work commenced “the Temple Mount”1 would provide an important clue, around 536 BC on the site of the First Temple, which the wouldn’t you? Babylonians had destroyed. The new Temple was simpler and more modest than its impressive predecessor had It’s a bit like the facetious query about who’s buried in been.2 Centuries later, when Yeshua sat contemplatively Grant’s tomb. Who else would be in that tomb but Mr. on the Mount of Olives with His disciples (Matt. 24), they Grant and what else would have been on the Temple looked down on the Temple Mount as King Herod’s work- Mount but the Temple? ers were busily at work remodeling and expanding the But not everyone agrees. -

The Jerusalem Archaeological Park Website Project

The Jerusalem Archaeological Park Website Project Y. Baruch1, R. Kudish-Vashdi1 and L. Ayzencot2 1 Israel Antiquities Authority, [email protected] [email protected] 2 EagleShade, Israel [email protected] Abstract.The archpark.org.il web-site presents a survey of the history and archaeology of Jerusalem. It is dedicated to the history and archaeology of Jerusalem from the Early Bronze Age until the Ottoman period. Its pivot is a dynamic time line, enhancing focal periods and events in the city’s history. Internal links lead to complementary information, e.g., historical sources. A bibliography, arranged by periods and themes, is also available. The site holds a detailed description of a 3D virtual model of the Temple Mount. One of its unique features are the interactive maps, displaying the results of the ongoing excavations of the city from the 19th century. The IAA publications department scientifically and grammatically edited all the texts, which were also refereed by leading scholars. Keywords: Jerusalem Archaeological Park, Temple Mount, David, Jewish Antiquities, The First Temple, Judah, Herod, Josephus, New Testament, Jesus, year 70 CE, Second Temples, Robinson’s Arch, Upper City, Real-Time Visual Simulation, the Herodian Temple Mount Virtual Reconstruction Model, Ethan and Marla Davidson Center, Israel Antiquities Authority, The Early Islamic Period, The Umayyad period (660–750, Early Islamic Art and Architecture, The Jerusalem gates, The gates of the Temple Mount, Hulda gates, Kiponus gate, El-Aqsa, Tyropoeon Valley 1. Introduction Hundreds of archaeological research years of Jerusalem have left us with a huge amount of information that occupies a lot of bookshelves in the libraries and archives. -

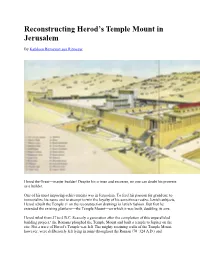

Reconstructing Herod's Temple Mount in Jerusalem

Reconstructing Herod’s Temple Mount in Jerusalem By Kathleen RitmeyerLeen Ritmeyer Herod the Great—master builder! Despite his crimes and excesses, no one can doubt his prowess as a builder. One of his most imposing achievements was in Jerusalem. To feed his passion for grandeur, to immortalize his name and to attempt to win the loyalty of his sometimes restive Jewish subjects, Herod rebuilt the Temple (1 on the reconstruction drawing) in lavish fashion. But first he extended the existing platform—the Temple Mount—on which it was built, doubling its size. Herod ruled from 37 to 4 B.C. Scarcely a generation after the completion of this unparalleled building project,a the Romans ploughed the Temple Mount and built a temple to Jupiter on the site. Not a trace of Herod’s Temple was left. The mighty retaining walls of the Temple Mount, however, were deliberately left lying in ruins throughout the Roman (70–324 A.D.) and Byzantine (324–640 A.D.) periods—testimony to the destruction of the Jewish state. The Islamic period (640–1099) brought further eradication of Herod’s glory. Although the Omayyad caliphs (whose dynasty lasted from 633 to 750) repaired a large breach in the southern wall of the Temple Mount, the entire area of the Mount and its immediate surroundings was covered by an extensive new religio-political complex, built in part from Herodian ashlars that the Romans had toppled. Still later, the Crusaders (1099–1291) erected a city wall in the south that required blocking up the southern gates to the Temple Mount. -

Israel and Judah: 18. Temple Interior and Dedication

Associates for Scriptural Knowledge • P.O. Box 25000, Portland, OR 97298-0990 USA © ASK, March 2019 • All rights reserved • Number 3/19 Telephone: 503 292 4352 • Internet: www.askelm.com • E-Mail: [email protected] How the Siege of Titus Locates the Temple Mount in the City of David by Marilyn Sams, July 2016 Formatted and annotated by David Sielaff, March 2019 This detailed research paper by independent author Marilyn Sams is one of several to follow her 2015 book, The Jerusalem Temple Mount Myth. Her book was inspired by a desire to prove (or disprove) Dr. Ernest Martin’s research in The Temples That Jerusalem Forgot. Ms. Sams wrote a second book in 2017, The Jerusalem Temple Mount: A Compendium of Ancient Descriptions expanding the argument in her first book, itemizing and analyzing 375 ancient descriptions of the Temple, Fort Antonia, and environs, all confirming a Gihon location for God’s Temples.1 Her books and articles greatly advance Dr. Martin’s arguments. David Sielaff, ASK Editor Marilyn Sams: The siege of Titus has been the subject of many books and papers, but always from the false perspective of the Jerusalem Temple Mount’s misidentification.2 The purpose of this paper is to illuminate additional aspects of the siege, in order to show how they cannot reasonably be applied to the current models of the temple and Fort Antonia, but can when the “Temple Mount” is identified as Fort Antonia. Conflicts Between the Rebellious Leaders Prior to the Siege of Titus A clarification of the definition of “Acra” is crucial to understanding the conflicts between John of Gischala and Simon of Giora, two of the rebellious [Jewish] faction leaders, who divided parts of Jerusalem 1 Her second book shows the impossibility of the so-called “Temple Mount” and demonstrate the necessity of a Gihon site of the Temples. -

The Hashemite Custodianship of Jerusalem's Islamic and Christian

THE HASHEMITE CUSTODIANSHIP OF JERUSALEM’S ISLAMIC AND CHRISTIAN HOLY SITES 1917–2020 CE White Paper The Royal Aal Al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought THE HASHEMITE CUSTODIANSHIP OF JERUSALEM’S ISLAMIC AND CHRISTIAN HOLY SITES 1917–2020 CE White Paper The Royal Aal Al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought THE HASHEMITE CUSTODIANSHIP OF JERUSALEM’S ISLAMIC AND CHRISTIAN HOLY SITES 1917–2020 CE Copyright © 2020 by The Royal Aal Al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought All rights reserved. No part of this document may be used or reproduced in any manner wthout the prior consent of the publisher. Cover Image: Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem © Shutterstock Title Page Image: Dome of the Rock and Jerusalem © Shutterstock isbn 978–9957–635–47–3 Printed in Jordan by The National Press Third print run CONTENTS ABSTRACT 5 INTRODUCTION: THE HASHEMITE CUSTODIANSHIP OF THE HOLY SITES IN JERUSALEM 7 PART ONE: THE ARAB, JEWISH, CHRISTIAN AND ISLAMIC HISTORY OF JERUSALEM IN BRIEF 9 PART TWO: THE CUSTODIANSHIP OF THE ISLAMIC HOLY SITES IN JERUSALEM 23 I. The Religious Significance of Jerusalem and its Holy Sites to Muslims 25 II. What is Meant by the ‘Islamic Holy Sites’ of Jerusalem? 30 III. The Significance of the Custodianship of Jerusalem’s Islamic Holy Sites 32 IV. The History of the Hashemite Custodianship of Jerusalem’s Islamic Holy Sites 33 V. The Functions of the Custodianship of Jerusalem’s Islamic Holy Sites 44 VI. Termination of the Islamic Custodianship 53 PART THREE: THE CUSTODIANSHIP OF THE CHRISTIAN HOLY SITES IN JERUSALEM 55 I. The Religious Significance of Jerusalem and its Holy Sites to Christians 57 II. -

Boundaries, Barriers, Walls

1 Boundaries, Barriers, Walls Jerusalem’s unique landscape generates a vibrant interplay between natural and built features where continuity and segmentation align with the complexity and volubility that have characterized most of the city’s history. The softness of its hilly contours and the harmony of the gentle colors stand in contrast with its boundar- ies, which serve to define, separate, and segregate buildings, quarters, people, and nations. The Ottoman city walls (seefigure )2 separate the old from the new; the Barrier Wall (see figure 3), Israelis from Palestinians.1 The former serves as a visual reminder of the past, the latter as a concrete expression of the current political conflict. This chapter seeks to examine and better understand the physical realities of the present: how they reflect the past, and how the ancient material remains stimulate memory, conscious knowledge, and unconscious perception. The his- tory of Jerusalem, as it unfolds in its physical forms and multiple temporalities, brings to the surface periods of flourish and decline, of creation and destruction. TOPOGRAPHY AND GEOGRAPHY The topographical features of Jerusalem’s Old City have remained relatively con- stant since antiquity (see figure ).4 Other than the Central Valley (from the time of the first-century historian Josephus also known as the Tyropoeon Valley), which has been largely leveled and developed, most of the city’s elevations, protrusions, and declivities have maintained their approximate proportions from the time the city was first settled. In contrast, the urban fabric and its boundaries have shifted constantly, adjusting to ever-changing demographic, socioeconomic, and political conditions.2 15 Figure 2. -

Temple in Jerusalem Coordinates: 31.77765, 35.23547 from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Log in / create account article discussion edit this page history Temple in Jerusalem Coordinates: 31.77765, 35.23547 From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Bet HaMikdash ; "The Holy House"), refers to Part of a series of articles on ,שדקמה תיב :The Temple in Jerusalem or Holy Temple (Hebrew a series of structures located on the Temple Mount (Har HaBayit) in the old city of Jerusalem. Historically, two Jews and Judaism navigation temples were built at this location, and a future Temple features in Jewish eschatology. According to classical Main page Jewish belief, the Temple (or the Temple Mount) acts as the figurative "footstool" of God's presence (Heb. Contents "shechina") in the physical world. Featured content Current events The First Temple was built by King Solomon in seven years during the 10th century BCE, culminating in 960 [1] [2] Who is a Jew? ∙ Etymology ∙ Culture Random article BCE. It was the center of ancient Judaism. The Temple replaced the Tabernacle of Moses and the Tabernacles at Shiloh, Nov, and Givon as the central focus of Jewish faith. This First Temple was destroyed by Religion search the Babylonians in 587 BCE. Construction of a new temple was begun in 537 BCE; after a hiatus, work resumed Texts 520 BCE, with completion occurring in 516 BCE and dedication in 515. As described in the Book of Ezra, Ethnicities Go Search rebuilding of the Temple was authorized by Cyrus the Great and ratified by Darius the Great. Five centuries later, Population this Second Temple was renovated by Herod the Great in about 20 BCE. -

Model of Ancient Jerusalem.Pdf

II The model represents Ancient Jerusalem in 66 C.E. at the beginning of the First Revolt against Rome. '.'..!'[71'l1 Its scale is I: 50 (2 ems. equal one metre, )4: inch - one' 1\ foot). An average man in scale would be 3~ ems. or 12/5 in- The model is reached opposite the tower Psepmnus (1 on ches high. The model has been constructed as far as possible of ~e.I~I~ the plan) the north-western corner tower in the Outer or Third ,~ the original materials used at the time, marble. stone and wood, Wall. copper and iron. Ancient Jerusalem was defended by three such walls on its The sources used in planning the model were the Mishnah, vulnerable northern side, while a single wall was sufficient on the Tosephtha, the Talmuds. Josephus and the New Testament. the west, south and east, because of the deep valleys surround- Psephinus Tower The construction of the model is due to the initiative and ing the city on these sides. The Third Wall was begun by King resources of Mr. Hans Kroch. The archaeological and topogra- Agrippa I (41-44 C.E.) and completed at the beginning of the phical data were supplied by Prof. M. Avi-Yonah, Hebrew Uni- First Revolt against Rome (66 C.E.). Its corner tower, Psephi- versity, Jerusalem, one of the foremost living authorities on the nus, was octagonal in shape. Its original height was 35 m. or subject. Mrs. Eva Avi-Yonah drew the plans, sections and 1]5 feet, which corresponds to 0.70 m. -

Jerusalem Under David and Solomon

JERUSALEM UNDER DAVID AND SOLOMON. WE have seen that the J ebusite fortress, which David took and called David's-Burgh-our versions mislead by their translation : City of David-lay on the Eastern Hill, south of and below the site of the later Tempi~, and just above Gil;ton, the present well of our Lady Mary. To this conclusion we seem shut up by the Biblical evidence ; and it is supported by the topography. But for the questions to which we now proceed the evidence is more precarious. What was the size of the Jebusite town around the Stronghold? And how much did David add to it? To these questions we are not able to find definite answers, in either the topography, the archaeology or the Biblical data. In fact there is almost no archaeological evidence in Jerusalem itself. The Biblical references are meagre and the topographical data are inconclusive. 1.-THE JEBUSITE TowN. That a Jebusite township existed around or beside the stronghold ~ion is as certain as that from remote times it was called Jerusalem. More probably than not it lay on the same Eastern Hill as the Stronghold, covering the rest of Ophel down to what was afterwards known as Siloam-more probably, I say, for its people would thus secure the shelter of the Stronghold and be near to the spring of Gil;ton. Nor does the narrative of David's capture of ~ion introduce or imply anything else. Accord ing to this David ma.rched:from Hebron to Jerusalem FEBRUARY, ,1905. 6 VOL. XI. -

INSTITUTE of JERUSALEM STUDIES JERUSALEM of INSTITUTE Winter 2017 Winter

Jerusalem: Fifty Years of Occupation Nazmi al-Jubeh Ribat in Palestine Kenny Schmitt Revocation of Residency of Palestinians in Jerusalem Tamara Tawfiq Tamimi Benefactresses of Waqf and Good Deeds Şerife Eroğlu Memiş Winter 2017 Jerusalem and Bethlehem Immigrant Families to Chile Bernard Sabella Resting in Peace in No Man’s Land at the Jerusalem War Cemetery Yfaat Weiss Filastinʼs Changing Attitude toward Early Zionism Emanuel Beška The Husayni Neighborhood in Jerusalem Winter 2017 Mahdi Sabbagh How Israel Legalizes Forcible Transfer: The Case of Occupied Jerusalem Report by Jerusalem Legal Aid and Human Rights Center (JLAC) Trump vs. a Global Consensus and International Law Infographics by Visualizing Palestine www.palestine-studies.org INSTITUTE OF JERUSALEM STUDIES Editors: Salim Tamari and Issam Nassar Associate Editors: Penny Johnson and Alex Winder Managing Editor: Carol Khoury Advisory Board Yazid Anani, A. M. Qattan Foundation, Ramallah Rochelle Davis, Georgetown University, USA Beshara Doumani, Brown University, USA Michael Dumper, University of Exeter, UK Rema Hammami, Birzeit University, Birzeit George Hintlian, Christian Heritage Institute, Jerusalem Huda al-Imam, Palestine Accueil, Jerusalem Omar Imseeh Tesdell, Birzeit University, Birzeit Nazmi al-Jubeh, Birzeit University, Birzeit Hasan Khader, al-Karmel Magazine, Ramallah Rashid Khalidi, Columbia University, USA Roberto Mazza, University of Limerick, Ireland Yusuf Natsheh, al-Quds University, Jerusalem Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian, Mada al-Carmel, Haifa Tina Sherwell, International Academy of Art Palestine, Ramallah The Jerusalem Quarterly (JQ) is published by the Institute of Jerusalem Studies (IJS), an affiliate of the Institute for Palestine Studies. The journal is dedicated to providing scholarly articles on Jerusalem’s history and on the dynamics and trends currently shaping the city. -

“The Second Hill, Which Bore the Name of Acra, and Supported The

Nahshon Szanton and Ayala Zilberstein “The Second Hill, which Bore the Name of Acra, and Supported the Lower City…” A New Look at the Lower City of Jerusalem in the end of the Second Temple Period Nahshon Szanton and Ayala Zilberstein Israel Antiquities Authority | Tel Aviv University 29* ”T“The Second Hil, which Bore the Name of Acra, and Supported the Lower ity“ The ancient core of the city of Jerusalem developed during early antiquity, as well as during the first generations of the Second Temple period, in the area of the southeastern hill bound between central streambeds – the Kidron Valley in the east and the Tyropoeon in the west. Only in the Late Hellenistic period, and more so in the Early Roman period, did the city expand westward toward the southwestern hill, and later still to the northern hill. Josephus’ description of Jerusalem on the eve of its destruction is the most detailed ancient source we have, and serves as a basis for every discussion about the city’s plan. “It was built, in portions facing each other, on two hills separated by a central valley in which the tiers of houses ended. Of these hills that on which the upper city lay was far higher and had a straighter ridge than the other…the second hill, which bore the name of Acra and supported the Lower City, was a hog’s back.” (War V, 136–137, trans. H. St. J. Thackeray). Zilberstein (2016: 100–101) has recently been discussed about the lack of the dichotomic boundaries between the two neighborhoods, which conventional research had reconstructed boundaries, that as though, having perpetuated socioeconomic gaps. -

Archaeology and Politics in Jerusalem's Historic Basin 2018

Archaeology and Politics in Jerusalem’s Historic Basin Annual Report - 2018 Written by: Talya Ezrahi, Yonathan Mizrachi December 2018 2018 has seen record levels of government investment in archaeological archaeological sites and heritage policy together with the weakening of Palestinian tourism ventures in Jerusalem’s Historic Basin. New projects, such as the cable car presence in the Historic Basin are detrimental to the preservation of Jerusalem’s from West Jerusalem to the neighborhood of Silwan/City of David, join ongoing multicultural heritage and undermines the cultural infrastructure underlying the development works to create a network of tourist sites which are transforming feasibility of dividing sovereignty over the city. Jerusalem’s Historic Basin from a multicultural historic city to a series of tourist Archaeological-tourism ventures in the Historic Basin in 2018 can be roughly attractions shaped by a Judeo-centric narrative. Driven by a religious nationalist grouped into three categories: agenda, the excavation, conservation and development works in the city’s historic 1. Extensive excavations - both traditional stratigraphic excavations and sites have become a central feature of the settlement project, with far-reaching excavations in underground tunnels implications for future negotiations over sovereignty. This process is facilitated 2. The development of these sites into tourist attractions and linking the various by tightening cooperation between the right-wing settler movement and the sites through a network of passages and routes above and underground. Government of Israel and record levels of investment in projects that prioritize a 3. New forms of transport and the creation of new routes, chief amongst them is Jewish identity for the historic city.