Temple Mount Faithful – Amutah Et Al V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

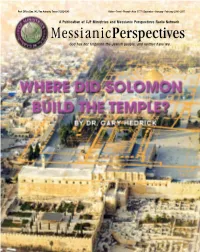

Where Did Solomon Build the Temple? by Dr

Post Office Box 345, San Antonio, Texas 78292-0345 Kislev –Tevet– Shevat–Adar 5777 / December– January– February 2016–2017 A Publication of CJF Ministries and Messianic Perspectives Radio Network MessianicPerspectives ® God has not forgotten the Jewish people, and neither have we. e are living in tumultuous times. Many things that Historical Background Wwe’ve always taken for granted are being called into question. The people of Israel had three central places of worship in ancient times: the Tabernacle, the First Temple, and the One hotly-disputed question these days is, “Were the an- Second Temple. Around 538 BC, the Jewish captives were cient Temples really on the Temple Mount?” You’d think released by King Cyrus of Persia to return from exile to the fact that Mount Moriah (and the manmade plat- their Land. Zerubbabel and Joshua the priest led the ef- form around it) has been known for many centuries as fort to rebuild the Second Temple, and work commenced “the Temple Mount”1 would provide an important clue, around 536 BC on the site of the First Temple, which the wouldn’t you? Babylonians had destroyed. The new Temple was simpler and more modest than its impressive predecessor had It’s a bit like the facetious query about who’s buried in been.2 Centuries later, when Yeshua sat contemplatively Grant’s tomb. Who else would be in that tomb but Mr. on the Mount of Olives with His disciples (Matt. 24), they Grant and what else would have been on the Temple looked down on the Temple Mount as King Herod’s work- Mount but the Temple? ers were busily at work remodeling and expanding the But not everyone agrees. -

On Changing the Immutable by Marc B. Shapiro,The History and Dating

וְהָאֱמֶת וְהַשָּׁלוֹם On Changing the ;אֱהָבוּ Immutable by Marc B. Shapiro On Changing the Immutable by ;וְהָאֱמֶת וְהַשָּׁלוֹם אֱהָבוּ Marc B. Shapiro By Yitzchok Stroh Professor Marc Shapiro’s latest work, Changing the Immutable, contains considerable interesting and pertinent information for the student of Jewish history. As stated on the cover, the author attempts to reveal how the (Jewish) orthodox ‘establishment’ silences both past and present dissenting voices through “Orthodox Judaism Rewriting Its History.” I don’t intend this to be a review of the entire work (that would take a lot more time and space), however I did want to share some of my frustration here, because I sense that the author’s bias affected his objectivity, and I am afraid that many a reader will be left with an impression that in many ways does not reflect the reality of this complex topic. In this article, I would like to examine one passage of Shapiro’s work to illustrate this point. In chapter eight, entitled, “Is the truth really that important?” Shapiro writes: Because my purpose in this chapter is to chart the outer limits of what has been viewed as acceptable when it comes to falsehood and deception. I will be focusing on the more ‘liberal’ positions. My aim is to show just how far some rabbinic decisors were willing to go in sanctioning deviations from the truth. One must bear in mind, however, that there are often views in opposition to the ones I shall be examining. Perhaps this knowledge can serve as a counterweight to the shock that many readers will experience upon learning of some of the positions I will mention. -

Israel in 1982: the War in Lebanon

Israel in 1982: The War in Lebanon by RALPH MANDEL LS ISRAEL MOVED INTO its 36th year in 1982—the nation cele- brated 35 years of independence during the brief hiatus between the with- drawal from Sinai and the incursion into Lebanon—the country was deeply divided. Rocked by dissension over issues that in the past were the hallmark of unity, wracked by intensifying ethnic and religious-secular rifts, and through it all bedazzled by a bullish stock market that was at one and the same time fuel for and seeming haven from triple-digit inflation, Israelis found themselves living increasingly in a land of extremes, where the middle ground was often inhospitable when it was not totally inaccessible. Toward the end of the year, Amos Oz, one of Israel's leading novelists, set out on a journey in search of the true Israel and the genuine Israeli point of view. What he heard in his travels, as published in a series of articles in the daily Davar, seemed to confirm what many had sensed: Israel was deeply, perhaps irreconcilably, riven by two political philosophies, two attitudes toward Jewish historical destiny, two visions. "What will become of us all, I do not know," Oz wrote in concluding his article on the develop- ment town of Beit Shemesh in the Judean Hills, where the sons of the "Oriental" immigrants, now grown and prosperous, spewed out their loath- ing for the old Ashkenazi establishment. "If anyone has a solution, let him please step forward and spell it out—and the sooner the better. -

The Bar and Bat Mitzvah Services 12

TEMPLE BETH EMETH Table of Contents Contact Us 2 Welcome Letter 3 Bar and Bat Mitzvah Brit (Covenant) 4 What is a Bat or Bar Mitzvah? 6 The Brit (Covenant) Explained: TBE Commitment 7 The Brit (Covenant) Explained: Bat or Bar Mitzvah Commitment 10 The Bar and Bat Mitzvah Services 12 After Your Bat or Bar Mitzvah 14 Shabbat Weekend Honors, Opportunities, and Obligations 16 Bar or Bat Mitzvah Logistics 17 Glossary 21 Service- and Celebration-related Checklists 26 Appendix A: Hosting the Saturday Congregational Kiddush 30 Appendix B: Hosting a Private Celebration at TBE 31 Appendix C: Resources for Hosting a Bat or Bar Mitzvah Celebration at TBE 32 Appendix D: Mitzvah Project Opportunities for TBE Bat and Bar Mitzvah Students 34 Appendix E: Usher Instructions 36 Appendix F: Additional Resources 38 For any questions or concerns not addressed within this guide, please contact Cantor Hayut. 1 Contact Us Call the Temple’s phone number: (734) 665-4744 Fax: 734-665-9237 Website: http://www.templebethemeth.org Hours: Mon-Thurs: 9am - 5pm Fri: 9am - 3pm Staff Josh Whinston, Rabbi Ext: 212 [email protected] Regina S. Lambert-Hayut, Cantor Ext: 227 [email protected] Rabbi Daniel Alter, Director of Education Ext: 207 [email protected] Clergy Assistant Ext: 210 Melissa Sigmond, Executive Director Ext: 206 [email protected] Mike Wolf, Genesis Administrator Ext: 200 [email protected] www.genesisa2.org For any questions or concerns not addressed within this guide, please contact Cantor Hayut. 2 Dear Bar and/or Bat Mitzvah Family, Mazel tov as you begin this exciting journey! The celebration of a child becoming Bat or Bar Mitzvah is one of the highlights in the life cycle of a Jewish family. -

Philo Ng.Pdf

PHILO AND THE NAMES OF GOD By A. MARMORSTEIN,Jews College, London IN A recent work on the allegorical exegesis of Philo of Alexandria' Philo's views and teachings as to the Hebrew names of God are once more discussed and analyzed. The author repeats and shares the old opinion, elaborated and propagated by Zacharias Frankel and others that Philo was more or less ignorant of the Hebrew tongue. Philo's treat- ment of the divine names is put in the first line of witnesses to corroborate this literary verdict. This question touches wider and more important problems than the narrow ques- tion whether Philo knew Hebrew, or not,2 and if the former is the case how far his knowledge, and if the latter is true how far his ignorance went. For the theologians generally some important historical and theological problems, for Jewish theology especially, besides these, literary and relig- ious questions as to the date and origin of religious concep- tions, and the antiquity and value of our sources are involved. Philo is criticized for having no idea2 of the equivalent names used by the LXX for the Tetragrammaton and Elohim respectively. The former is translated KVptOS, the latter 4hos. This omission is the more serious since the distinction between these two names is one of Philo's chief doctrines. We are referred to a remark made by Z. Frankel about ' Edmund Stein, Die allegorische Exegese des Philo aus Alexandreia; Giessen, 1929. (Beihefte Zur ZAW. No. 51.) 2 Ibid., p. 20, for earlier observations see G. Dalman, Adonaj, 59.1, Daehne, Geschichtliche Darstellung, I 231, II 51; Freiidenthal, Alexander Polyhistor, p. -

477 Appendix 3B, I. NAMES Supplemental Listing ABIAH

Appendix 3B, I. NAMES Supplemental Listing Note: This listing primarily offers additional avenues for comparison. Many of its names are explored in other segments (e.g. citations related to post-exilic proceedings are referenced in Appendix 3B, II, Detail A). Biblical encyclopedias comparable to those employed in this work will enable locating verses for some few items not referenced elsewhere in this work. ABIAH - see Abijah/Abijam. ABIEL - see Jehiel[/Abiel]. ABI-EZER (1) (a) (Manasseh-Machir-) Gilead and Gilead’s sister, Hammoleketh/Hammolecheth; (Hammoleketh-) Abiezer. 1 Chronicles 7:17-18; (b) (Asenath + Joseph-Manasseh-Machir-Sons of Gilead-) Jeezer/sons of Abiezer. Numbers 26:28-30; Joshua 17:1-2; (c) (Aaron-Eleazar-Phinehas-) Abiezer/Abishua in the chief priest line; (d) (Joash, the Abiezrite-) Judge Gideon; Judges 6:11--refer to Appendices 1C, sub-part VI, C, and 3B, II, sub-part II, A, and Attachment 1. (2) Ophrah of the Abi-ezrites.” Judges 6:24, 8:32. (3) Abiezer “the Anethothite/[Anathothite]” “of the Benjaminites”--one of king David’s 37 most valiant captains; head of a divisional force of 24,000 that served the king the ninth month of the year. 2 Samuel 23:27; 1 Chronicles 11:28, 27:12. ABIJAH/ABIAH/ABIJAM (1) (Benjamin-Becher-) Abiah. 1 Chronicles 7:8. (2) (Abiah/Abijah + Hezron -) Ashur, “father of Tekoa.” Refer to Appendix 1C, Attachment 1, at fn. 20. (3) “[T]he name of his/[Samuel’s (+ Hannah) ] son firstborn Joel, and the name of his second Abiah[/Abijah].” 1 Samuel 8:2; 1 Chronicles 6:28; refer also to Elkanah, this appendix. -

THE TEMPLE B'nei Mitzvah Handbook

THE TEMPLE ESTABLISHED 1867 B’nei Mitzvah Handbook 5778 = 2018 “And you shall teach them faithfully to your children.” Accredited by the National Association of Temple Educators Table of Contents Welcome Letter 3 Welcome & Overview Bar/Bat Mitzvah: Our Mission 4 Let us welcome you to the bar/bat mitzvah process at The Temple. History of B’nei Mitzvah 4 Prerequisites of Bar/Bat Mitzvah 5 B’nei Mitzvah 101 The Ceremony 6 Everything you need to know about what to do leading up to the bar/bar Family Participation 7 mitzvah, prerequisites, the ceremony Prayer Book 7 itself, family participation, and more. B’nei Mitzvah Tutoring 8 B’nei Mitzvah in Israel 8 B’nei Mitzvah Timeline 9 Policies and Procedures Temple Policies 10 This will lay out a complete timeline Picture in the Bulletin 11 and all of our policies and procedures vis-a-vis the bar/bat mitzvah. Ushers 11 13 by 13 Mitzvah Program 12 The 13 by 13 Program The Mitzvah of Torah 12 These are the mitzvot that your child will complete along the way. The Mitzvah of Avodah 13 The Mitzvah of G’milut Chasadim 14 Additional Mitzvah Suggestions 16 Additional Mitzvot MAZON: A Jewish Response to Hunger 18 More resources for mitzvot. Mitzvah Journal 19 Keep Track Notes 23 We encourage you to take notes. Information Form 24 Forms Honors Form 25 The forms you’ll need to fill out. Welcome Dear Temple Family, Mazal tov! The celebration of a child’s becoming a bar or bat mitzvah is one of the greatest events in the life cycle of a Jewish family. -

Priesthood, Cult, and Temple in the Aramaic Scrolls from Qumran

PRIESTHOOD, CULT, AND TEMPLE IN THE ARAMAIC SCROLLS PRIESTHOOD, CULT, AND TEMPLE IN THE ARAMAIC SCROLLS FROM QUMRAN By ROBERT E. JONES III, B.A., M.Div. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University © Copyright by Robert E. Jones III, June 2020 McMaster University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2020) Hamilton, Ontario (Religious Studies) TITLE: Priesthood, Cult, and Temple in the Aramaic Scrolls from Qumran AUTHOR: Robert E. Jones III, B.A. (Eastern University), M.Div. (Pittsburgh Theological Seminary) SUPERVISOR: Dr. Daniel A. Machiela NUMBER OF PAGES: xiv + 321 ii ABSTRACT My dissertation analyzes the passages related to the priesthood, cult, and temple in the Aramaic Scrolls from Qumran. The Aramaic Scrolls comprise roughly 15% of the manuscripts found in the Qumran caves, and testify to the presence of a flourishing Jewish Aramaic literary tradition dating to the early Hellenistic period (ca. late fourth to early second century BCE). Scholarship since the mid-2000s has increasingly understood these writings as a corpus of related literature on both literary and socio-historical grounds, and has emphasized their shared features, genres, and theological outlook. Roughly half of the Aramaic Scrolls display a strong interest in Israel’s priestly institutions: the priesthood, cult, and temple. That many of these compositions display such an interest has not gone unnoticed. To date, however, few scholars have analyzed the priestly passages in any given composition in light of the broader corpus, and no scholars have undertaken a comprehensive treatment of the priestly passages in the Aramaic Scrolls. -

The Severity and Mercy of God 2 Samuel 24 Several Years Ago A

The Severity and Mercy of God 2 Samuel 24 Several years ago a man in his 50s came to faith in Christ and started reading the Bible for the first time. About once a week he would come into my office to talk about the things he was reading in the Old Testament. Quite often the things he wanted to talk about were the shocking, unusual things that God did or that God commanded – such as when God commanded the Israelites to kill every man, woman, and child when they conquered a city (see Deut. 3:6, 1 Samuel 15:3). Those discussions reminded me that some of what is written in the Old Testament can be troubling. Perhaps you’ve been shocked at some of the things we’ve seen this fall in the life of David. But it’s not just the Old Testament. When you read the gospels, you learn that Jesus talked about hell more than anybody else. For example, Jesus told His followers in Matthew 10:28: 28 "And do not fear those who kill the body, but are unable to kill the soul; but rather fear Him who is able to destroy both soul and body in hell. Hell is a place of conscious, eternal punishment apart from the presence of God. Jesus’ point is that if God has the power to banish people to the destruction of hell, we should “fear” Him (instead of merely fearing other people). We find throughout Scripture what is sometimes called “the severity of God.” And yet the overarching plot of the Bible is that God loves us so much that He sent His one and only Son to die for our sins. -

The Hashemite Custodianship of Jerusalem's Islamic and Christian

THE HASHEMITE CUSTODIANSHIP OF JERUSALEM’S ISLAMIC AND CHRISTIAN HOLY SITES 1917–2020 CE White Paper The Royal Aal Al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought THE HASHEMITE CUSTODIANSHIP OF JERUSALEM’S ISLAMIC AND CHRISTIAN HOLY SITES 1917–2020 CE White Paper The Royal Aal Al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought THE HASHEMITE CUSTODIANSHIP OF JERUSALEM’S ISLAMIC AND CHRISTIAN HOLY SITES 1917–2020 CE Copyright © 2020 by The Royal Aal Al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought All rights reserved. No part of this document may be used or reproduced in any manner wthout the prior consent of the publisher. Cover Image: Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem © Shutterstock Title Page Image: Dome of the Rock and Jerusalem © Shutterstock isbn 978–9957–635–47–3 Printed in Jordan by The National Press Third print run CONTENTS ABSTRACT 5 INTRODUCTION: THE HASHEMITE CUSTODIANSHIP OF THE HOLY SITES IN JERUSALEM 7 PART ONE: THE ARAB, JEWISH, CHRISTIAN AND ISLAMIC HISTORY OF JERUSALEM IN BRIEF 9 PART TWO: THE CUSTODIANSHIP OF THE ISLAMIC HOLY SITES IN JERUSALEM 23 I. The Religious Significance of Jerusalem and its Holy Sites to Muslims 25 II. What is Meant by the ‘Islamic Holy Sites’ of Jerusalem? 30 III. The Significance of the Custodianship of Jerusalem’s Islamic Holy Sites 32 IV. The History of the Hashemite Custodianship of Jerusalem’s Islamic Holy Sites 33 V. The Functions of the Custodianship of Jerusalem’s Islamic Holy Sites 44 VI. Termination of the Islamic Custodianship 53 PART THREE: THE CUSTODIANSHIP OF THE CHRISTIAN HOLY SITES IN JERUSALEM 55 I. The Religious Significance of Jerusalem and its Holy Sites to Christians 57 II. -

The Straight Path: Islam Interpreted by Muslims by Kenneth W. Morgan

Islam -- The Straight Path: Islam Interpreted by Muslims return to religion-online 47 Islam -- The Straight Path: Islam Interpreted by Muslims by Kenneth W. Morgan Kenneth W. Morgan is Professor of history and comparative religions at Colgate University. Published by The Ronald Press Company, New York 1958. This material was prepared for Religion Online by Ted and Winnie Brock. (ENTIRE BOOK) A collection of essays written by Islamic leaders for Western readers. Chapters describe Islam's origin, ideas, movements and beliefs, and its different manifestations in Africa, Turkey, Pakistan, India, China and Indonesia. Preface The faith of Islam, and the consequences of that faith, are described in this book by devout Muslim scholars. This is not a comparative study, nor an attempt to defend Islam against what Muslims consider to be Western misunderstandings of their religion. It is simply a concise presentation of the history and spread of Islam and of the beliefs and obligations of Muslims as interpreted by outstanding Muslim scholars of our time. Chapter 1: The Origin of Islam by Mohammad Abd Allah Draz The straight path of Islam requires submission to the will of God as revealed in the Qur’an, and recognition of Muhammad as the Messenger of God who in his daily life interpreted and exemplified that divine revelation which was given through him. The believer who follows that straight path is a Muslim. Chapter 2: Ideas and Movements in Islamic History, by Shafik Ghorbal The author describes the history and problems of the Islamic society from the time of the prophet Mohammad as it matures to modern times. -

Worship and Devotions

License, Copyright and Online Permission Statement Copyright © 2018 by Chalice Press. Outlines developed by an Editorial Advisory Team of outdoor ministry leaders representing six mainline Protestant denominations. Purchase of this resource gives license for its use, adaptation, and copying for programmatic use at one outdoor ministry or day camp core facility/operation (hereinafter, “FACILITY”) for up to one year from purchase. Governing bodies that own and operate more than one FACILITY must buy one copy of the resource for each FACILITY using the resource. Copies of the files may be made for use only within each FACILITY for staff and volunteer use only. Each FACILITY’s one-year permission now includes the use of this material for one year at up to three additional venues to expand the FACILITY’s reach into the local community. Examples would include offering outdoor ministry experiences at churches, schools, or community parks that are not part of your core FACILITY program. Copies of the files are for programming use only by staff and volunteers, and distribution for resale is strictly prohibited in any form electronically or in hard copy such as printing, copying, website posting/re-posting, emails, etc. Use of sí se puede® is by permission from United Farmworkers Union and Cesar Chavez Foundation. Use of this phrase outside of camp activities is not covered by this purchase and must be negotiated directly with UFW. Use of “May Peace Prevail on Earth” is by permission from World Peace Prayer Society. It can be freely used to promote peace but not for any commercial venture.