Aceh Under Marital

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aceh Public Expenditure Analysis Spending For

ACEH PUBLIC EXPENDITURE ANALYSIS SPENDING FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND POVERTY REDUCTION ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report – the Aceh Public Expenditure Analysis (APEA) - is the result of collaborative efforts between the World Bank and four Acehnese universities: Syiah Kuala University and IAIN Ar-Raniry (Banda Aceh), Malikul Saleh University and Politeknik University (Lhokseumawe). This report was prepared by a core team led by Oleksiy Ivaschenko, Ahya Ihsan and Enrique Blanco Armas, together with Eleonora Suk Mei Tan and Cut Dian, included Patrick Barron, Cliff Burkley, John Cameron, Taufiq C. Dawood, Guy Jenssen, Rehan Kausar (ADB), Harry Masyrafah, Sylvia Njotomihardjo, Peter Rooney and Chairani Triasdewi. Syamsul Rizal (Syiah Kuala University) coordinated local partners and Djakfar Ahmad provided outreach to members of provincial and local governments. Wolfgang Fengler supervised the APEA-process and the production of this report. Victor Bottini, Joel Hellman and Scott Guggenheim provided overall guidance throughout the process. The larger team contributing to the preparation of this report consisted of Nasruddin Daud and Sufii, from the World Bank Andre Bald, Maulina Cahyaningrum, Ahmad Zaki Fahmi, Indra Irnawan, Bambang Suharnoko and Bastian Zaini and the following university teams: from Syiah Kuala University (Banda Aceh) - Razali Abdullah, Zinatul Hayati, Teuku M. Iqbalsyah, Fadrial Karmil, Yahya Kobat, Jeliteng Pribadi, Yanis Rinaldi, Agus Sabti, Yunus Usman and Teuku Zulham; from IAIN Ar-Raniry (Banda Aceh) - Fakhri Yacob; from Malikul Saleh University (Lhokseumawe ) - Wahyudin Albra, Jullimursyida Ganto and Andria Zulfa; from Polytechnic Lhokseumawe - Riswandi and Indra Widjaya. The APBD data was gathered and processed by Ridwan Nurdin, Sidra Muntahari, Cut Yenizar, Nova Idea, Miftachuddin, and Akhiruddin (GeRAK) for APBD data support. -

HISTORY, AUTHORITY and POWER a Case of Religious Violence in Aceh

JajatDOI: Burhanuddin 10.15642/JIIS.2014.8.1.112 -138 HISTORY, AUTHORITY AND POWER A Case of Religious Violence in Aceh Jajat Burhanudin1 UIN Syarif Hidayatullah, Jakarta – Indonesia | [email protected] Abstract: This article discusses the way Islam transformed into an ideology that potentially used as justification for violence. By analising the case of the murder of Teungku Ayub, leader of a small circle for basic religious learning (pengajian) in Bireun, Aceh, in 2012, the study reveals to the role of Islam as an ideology of mass movement to cleanse deviant tenet (aliran sesat) among the Acehnese. This is because of two reasons. First, the term of the veranda of Mecca (serambi Mekkah) remains considered as “holy word” in the Acehnese society today, which supports any Islamic agenda of purifying Aceh from aliran sesat. Secondly, the adoption of Islam into a formal body of state (Aceh province) represented by the implementation of Islamic law (sharīʻah). Both reasons above strengthen ulama in Aceh to facilitate the mass movement in the name of religion as well as the rationale background of the murder of Teungku Ayub. Keywords: ulama (teungku), Dien al Syariah, religious violence. Introduction This article attempts to shed light on the incident that took place in Biruen, a small town in Aceh, at 16 November 2012. It is located 1 I should thank to some people who assisted me during the field research in Aceh. They are Sahlan Hanafiyah, lecturer at State Islamic University ar-Raniri in Banda Aceh, and Setyadi Sulaiman as a research assistant from Jakarta. -

Daftar 34 Provinsi Beserta Ibukota Di Indonesia

SEKRETARIAT UTAMA LEMHANNAS RI BIRO KERJASAMA DAFTAR 34 PROVINSI BESERTA IBUKOTA DI INDONESIA I. PULAU SUMATERA 1. Nanggroe Aceh Darussalam : Banda Aceh 2. Sumatera Utara : Medan 3. Sumatera Selatan : Palembang 4. Sumatera Barat : Padang 5. Bengkulu : Bengkulu 6. Riau : Pekanbaru 7. Kepulauan Riau : Tanjung Pinang 8. Jambi : Jambi 9. Lampung : Bandar Lampung 10. Bangka Belitung : Pangkal Pinang II. PULAU KALIMANTAN 1. Kalimantan Barat : Pontianak 2. Kalimantan Timur : Samarinda 3. Kalimantan Selatan : Banjarmasin 4. Kalimantan Tengah : Palangkaraya 5. Kalimantan Utara : Tanjung Selor (Belum pernah melkskan MoU) III. PULAU JAWA 1. Banten : Serang 2. DKI Jakarta : Jakarta 3. Jawa Barat : Bandung 4. Jawa Tengah : Semarang 5. DI Yogyakarta : Yogyakarta 6. Jawa timur : Surabaya IV. PULAU NUSA TENGGARA & BALI 1. Bali : Denpasar 2. Nusa Tenggara Timur : Kupang 3. Nusa Tenggara Barat : Mataram V. PULAU SULAWESI 1. Gorontalo : Gorontalo 2. Sulawesi Barat : Mamuju 3. Sulawesi Tengah : Palu 4. Sulawesi Utara : Manado 5. Sulawesi Tenggara : Kendari 6. Sulawesi Selatan : Makassar VI. PULAU MALUKU & PAPUA 1. Maluku Utara : Ternate 2. Maluku : Ambon 3. Papua Barat : Manokwari 4. Papua ( Daerah Khusus ) : Jayapura *) Provinsi Terbaru Prov. Teluk Cendrawasih (Seruai) *) Provinsi Papua Barat (Sorong) 2 DAFTAR MoU DI LEMHANNAS RI Pemerintah/Non Pemerintah, BUMN/Swasta, Parpol, Ormas & Universitas *) PROVINSI 1. Gub. Aceh-10/5 16-11-2009 2. Prov. Sumatera Barat-11/5 08-12-2009 Prov. Sumbar-116/12 16-12-2015 3. Prov. Kep Riau-12/5 21-12-2009 Kep. Riau-112/5 16-12-2015 4. Gub. Kep Bangka Belitung-13/5 18-11-2009 5. Gub. Sumatera Selatan-14 /5 16-11-2009 Gub. -

Reconceptualising Ethnic Chinese Identity in Post-Suharto Indonesia

Reconceptualising Ethnic Chinese Identity in Post-Suharto Indonesia Chang-Yau Hoon BA (Hons), BCom This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Social and Cultural Studies Discipline of Asian Studies 2006 DECLARATION FOR THESES CONTAINING PUBLISHED WORK AND/OR WORK PREPARED FOR PUBLICATION This thesis contains sole-authored published work and/or work prepared for publication. The bibliographic details of the work and where it appears in the thesis is outlined below: Hoon, Chang-Yau. 2004, “Multiculturalism and Hybridity in Accommodating ‘Chineseness’ in Post-Soeharto Indonesia”, in Alchemies: Community exChanges, Glenn Pass and Denise Woods (eds), Black Swan Press, Perth, pp. 17-37. (A revised version of this paper appears in Chapter One of the thesis). ---. 2006, “Assimilation, Multiculturalism, Hybridity: The Dilemma of the Ethnic Chinese in Post-Suharto Indonesia”, Asian Ethnicity, Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 149-166. (A revised version of this paper appears in Chapter One of the thesis). ---. 2006, “Defining (Multiple) Selves: Reflections on Fieldwork in Jakarta”, Life Writing, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 79-100. (A revised version of this paper appears in a few sections of Chapter Two of the thesis). ---. 2006, “‘A Hundred Flowers Bloom’: The Re-emergence of the Chinese Press in post-Suharto Indonesia”, in Media and the Chinese Diaspora: Community, Communications and Commerce, Wanning Sun (ed.), Routledge, London and New York, pp. 91-118. (A revised version of this paper appears in Chapter Six of the thesis). This thesis is the original work of the author except where otherwise acknowledged. -

Description of Depression in People with Epilepsy in Aceh

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Bali Medical Journal (Bali MedJ) 2021, Volume 10, Number 2: 521-525 P-ISSN.2089-1180, E-ISSN: 2302-2914 Description of depression in people with epilepsy in Aceh Published by Bali Medical Journal Nova Dian Lestari1,2*, Nirwana Lazuardi Sary3, Arina Khairu Ummah4, Zulkarnain3, Nur Astini1,2 1Department of Neurology, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Syiah Kuala, Banda ABSTRACT Aceh, Indonesia; 2Department of Neurology, Dr Zainoel Background: Depression is the most common comorbid in people with epilepsy (PWE). Detection of depression in PWE is not Abidin Hospital, Banda Aceh, Indonesia; a routine examination at a neurology clinic because it takes a long time. The education of Acehnese people regarding epilepsy 3 Department of Physiology, Faculty of is still limited, leading to discrimination and stigma in society. It is not easy to carry out examinations, and the diagnosis is Medicine, Universitas Syiah Kuala, Banda Aceh, Indonesia; often overlooked. The objective of this study was to screen and to describe the characteristics of depression in PWE in Aceh. 4Undergraduate Medical Doctor Program, Method: This study was a descriptive observational study with the total respondents involved 41 PWEs. Detection of Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Syiah depression in PWE was conducted using the Neurological Disorders Depression Inventory for Epilepsy (NDDI-E), a valid, Kuala, Banda Aceh, Indonesia. reliable, shorter and more straightforward instrument test. The sample was determinate using the probability sampling method with a simple random sampling technique. *Corresponding author: Results: Our results found that 39% of respondents experienced depression, with the most NDDI-E scores ranged between Nova Dian Lestari; 11-15, with a percentage of 41.5%. -

Understanding Capture and Validate KYC Processes: Global Experiences, Challenges and Learnings

Understanding Capture and Validate KYC Processes: Global Experiences, Challenges and Learnings May 2019 Copyright © 2019 GSM Association Understanding Capture and Validate KYC Processes: Global Experiences, Challenges and Learnings v Digital Identity The GSMA represents the interests of mobile operators The GSMA Digital Identity Programme is uniquely worldwide, uniting more than 750 operators with over positioned to play a key role in advocating and raising 350 companies in the broader mobile ecosystem, awareness of the opportunity of mobile-enabled digital including handset and device makers, software companies, identity and life-enhancing services. Our programme works equipment providers and internet companies, as well as with mobile operators, governments and the development organisations in adjacent industry sectors. The GSMA also community to demonstrate the opportunities, address the produces the industry-leading MWC events held annually in barriers and highlight the value of mobile as an enabler of Barcelona, Los Angeles and Shanghai, as well as the Mobile digital identification. 360 Series of regional conferences. For more information, please visit the GSMA Digital Identity For more information, please visit the GSMA corporate website at www.gsma.com/digitalidentity website at www.gsma.com Follow GSMA Mobile for Development on Twitter: Follow the GSMA on Twitter: @GSMA @GSMAm4d This document is an output of a project funded by UK aid from the Department for International Development (DFID), for the benefit of developing countries. The views expressed are not necessarily those of DFID. Author: Matt Wilson, Senior Insights Manager, GSMA Rob Waddington, Futuresight Understanding Capture and Validate KYC Processes: Global Experiences, Challenges and Learnings v Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................. -

FX Harsono Gazing on Identity Menerawang Identitas Colophon

Man as an individual has the freedom to decide their own will’ is a meaningless quote. When one is declared to be valid as a citizen the freedom changed. For the Chinese, although they were born in Indonesia, they are still considered as migrant. Apart from Indonesian Citizenship certificate, they must also have other documents, where this regulation is not applied to ‘real’ Indonesians. The dichotomy of real-migrant, free-bonded, is presented in this work. The facial expressions, poses, interaction in the family that seems to be free and happy on one side; and on the other side facing legal-formal issues that specifically only applies on them The point is, the law becomes discriminative if it applies only to suppress a community group. FX HARSONO GAZING ON IDENTITY Menerawang Identitas Colophon GAZING ON IDENTITY Menerawang Identitas Solo Exhibition of FX Harsono ARNDT Fine Art Gillman Barracks Singapore 20 October – 20 November 2016 Exhibition Curator Lisa Polten Writer Didi Kwartanada Text Translator Elly Kent Photo FX Harsono Design for Catalogue Sari Handayani Printed in Yogyakarta, Indonesia in an edition of 500 ©2016, FX. Harsono and the author 4 Didi Kwartanada THE PAPERS THAT SURVEILLED Identity Cards and Suspicion of the Chinese From time to time, the slip of paper featuring passport photos and personal details, which we usually call an “identity card” (Ind: kartu identitas), becomes the subject on national debate. During the New Order (1966-1998), citizenship cards (known as the “Kartu Tanda Penduduk”/KTP in Indonesia) belonging to former political prisoners (Ind: tahanan politik or simply “tapol”) were stamped with a special code, as were those belonging to ethnic Chinese. -

The Case of Aceh, Indonesia Patrick Barron Erman Rahmant Kharisma Nugroho

THE CONTESTED CORNERS OF ASIA Subnational Conflict and International Development Assistance The Case of Aceh, Indonesia Patrick Barron Erman Rahmant Kharisma Nugroho The Contested Corners of Asia: Subnational Con!ict and International Development Assistance The Case of Aceh, Indonesia Patrick Barron, Erman Rahman, Kharisma Nugroho Authors : Patrick Barron, Erman Rahman, Kharisma Nugroho Research Team Saifuddin Bantasyam, Nat Colletta, (in alphabetical order): Darnifawan, Chairul Fahmi, Sandra Hamid, Ainul Huda, Julianto, Mahfud, Masrizal, Ben Oppenheim, Thomas Parks, Megan Ryan, Sulaiman Tripa, Hak-Kwong Yip World Bank counterparts ; Adrian Morel, Sonja Litz, Sana Jaffrey, Ingo Wiederhofer Perceptions Survey Partner ; Polling Centre Supporting team : Ann Bishop (editor), Landry Dunand (layout), Noni Huriati, Sylviana Sianipar Special thanks to ; Wasi Abbas, Matt Zurstrassen, Harry Masyrafah Lead Expert : Nat Colletta Project Manager : Thomas Parks Research Specialist and Perception Survey Lead : Ben Oppenheim Research Methodologist : Yip Hak Kwang Specialist in ODA to Con!ict Areas : Anthea Mulakala Advisory Panel (in alphabetical order) : Judith Dunbar, James Fearon, Nils Gilman, Bruce Jones, Anthony LaViña, Neil Levine, Stephan Massing, James Putzel, Rizal Sukma, Tom Wing!eld This study has been co-!nanced by the State and Peacebuilding Fund (SPF) of the World Bank. The !ndings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of the World Bank and its af!liated organizations, or those of the Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. Additional funding for this study was provided by UK Aid from the UK Government. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of The Asia Foundation or the funders. -

KYC Practices in Indonesia and the Opportunity for Implementing E-KYC to Accelerate Financial Inclusion

MSC Policy brief #24 KYC practices in Indonesia and the opportunity for implementing e-KYC to accelerate financial inclusion Agnes Salyanty, Arshi Aadil, Rahmatika Febrianti, Raunak Kapoor, and Sneha Sampath KYC practices in Indonesia and the opportunity for implementing e-KYC to accelerate financial inclusion Introduction and background In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Public infrastructure for electronic Know Your Government of India provided emergency Customer (e-KYC) has been critical to financial digital cash transfers to more than 300 million inclusion initiatives in many developing people within a month by utilizing the payment countries. E-KYC provides multiple benefits over system backed by Aadhaar, the foundational traditional paper-based KYC. It enables efficiency digital ID in the country. This included a total gains in terms of time, cost, and resource transfer of USD 3.8 billion (INR 280 billion) to requirements involved in the verification of the farmers, senior citizens, and women who were identity of an individual or entity. This ensures a identified quickly as they were beneficiaries of near real-time onboarding of a customer for any social protection programs. The digital payment financial product or service. Since an efficient infrastructure built around Aadhaar provides an KYC process is one of the most important and interoperable, cost-effective, quick, and secure costly aspects of any customer due diligence, payment solution using the digital ID to verify making it easy and cost-effective is the priority beneficiaries and authenticate transactions and of financial services providers. In addition, withdrawals. inefficiencies in the customer onboarding process can have a significant impact on the trust Countries have built robust architecture around of a potential customer in the financial service foundational identity systems that enable provider and consequently on the adoption and different stakeholders to access the identity uptake of its products and services. -

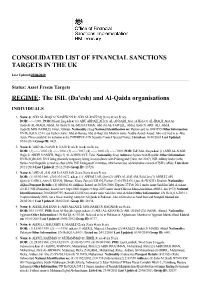

Consolidated List of Financial Sanctions Targets in the Uk

CONSOLIDATED LIST OF FINANCIAL SANCTIONS TARGETS IN THE UK Last Updated:29/04/2019 Status: Asset Freeze Targets REGIME: The ISIL (Da'esh) and Al-Qaida organisations INDIVIDUALS 1. Name 6: ABD AL-BAQI 1: NASHWAN 2: ABD AL-RAZZAQ 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. DOB: --/--/1961. POB: Mosul, Iraq a.k.a: (1) ABU ABDALLAH (2) AL-ANSARI, Abd, al-Hadi (3) AL-IRAQI, Abd Al- Hadi (4) AL-IRAQI, Abdal, Al-Hadi (5) AL-MUHAYMAN, Abd (6) AL-TAWEEL, Abdul, Hadi (7) ARIF ALI, Abdul, Hadi (8) MOHAMMED, Omar, Uthman Nationality: Iraqi National Identification no: Ration card no. 0094195 Other Information: UN Ref QI.A.12.01. (a) Fathers name: Abd al-Razzaq Abd al-Baqi, (b) Mothers name: Nadira Ayoub Asaad. Also referred to as Abu Ayub. Photo available for inclusion in the INTERPOL-UN Security Council Special Notice. Listed on: 10/10/2001 Last Updated: 07/01/2016 Group ID: 6923. 2. Name 6: 'ABD AL-NASIR 1: HAJJI 2: n/a 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. DOB: (1) --/--/1965. (2) --/--/1966. (3) --/--/1967. (4) --/--/1968. (5) --/--/1969. POB: Tall 'Afar, Iraq a.k.a: (1) ABD AL-NASR, Hajji (2) ABDELNASSER, Hajji (3) AL-KHUWAYT, Taha Nationality: Iraqi Address: Syrian Arab Republic.Other Information: UN Ref QDi.420. UN Listing (formerly temporary listing, in accordance with Policing and Crime Act 2017). ISIL military leader in the Syrian Arab Republic as well as chair of the ISIL Delegated Committee, which exercises administrative control of ISIL's affairs. Listed on: 20/11/2018 Last Updated: 23/11/2018 Group ID: 13720. -

Seeking the State from the Margins: from Tidung Lands to Borderlands in Borneo

Seeking the state from the margins From Tidung Lands to borderlands in Borneo Nathan Bond ORCID ID: 0000-0002-8094-9173 A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. December 2020 School of Social and Political Sciences The University of Melbourne i Abstract Scholarship on the geographic margins of the state has long suggested that life in such spaces threatens national state-building by transgressing state order. Recently, however, scholars have begun to nuance this view by exploring how marginal peoples often embrace the nation and the state. In this thesis, I bridge these two approaches by exploring how borderland peoples, as exemplars of marginal peoples, seek the state from the margins. I explore this issue by presenting the first extended ethnography of the cross-border ethnic Tidung and neighbouring peoples in the Tidung Lands of northeast Borneo, complementing long-term fieldwork with research in Dutch and British archives. This region, lying at the interstices of Indonesian Kalimantan, Malaysian Sabah and the Southern Philippines, is an ideal site from which to study borderland dynamics and how people have come to seek the state. I analyse understandings of the state, and practical consequences of those understandings in the lives and thought of people in the Tidung Lands. I argue that people who imagine themselves as occupying a marginal place in the national order of things often seek to deepen, rather than resist, relations with the nation-states to which they are marginal. The core contribution of the thesis consists in drawing empirical and theoretical attention to the under-researched issue of seeking the state and thereby encouraging further inquiry into this issue. -

Population Displacement and Mobility in Sumatra After the Tsunami

Population Displacement and Mobility in Sumatra after the Tsunami Clark Gray1, Elizabeth Frankenberg1, Thomas Gillespie2, Cecep Sumantri3, and Duncan Thomas1 August 2009 Abstract The Indian Ocean tsunami of December, 2004 was one of the most severe natural disasters in human history and resulted in extensive relocation by people living in damaged areas. We describe post-tsunami geographic mobility in the provinces of Aceh and North Sumatra in Indonesia, the area worst-affected by the tsunami. Data from a unique longitudinal survey of 10,000 households who were interviewed both before and after the tsunami are used to quantify and map various dimensions of mobility and to provide insights into the individual, household and contextual factors that influence mobility. Levels of mobility increased dramatically with the extent of tsunami damage. Displacement from heavily damaged areas occurred primarily beyond the community of origin. Results from multivariate statistical models indicate that in damaged areas individuals were displaced similarly across demographic and socioeconomic lines, and that semi-voluntary decisions about mobility were influenced by household assets and prior livelihood strategies. Keywords: tsunami, disaster, displacement, migration, Indonesia. 1 Duke University, 2 UCLA, 3 SurveyMeter, Yogyakarta, Indonesia Acknowledgements This project is part of a large, collaborative effort and we would like to thank our colleagues Jed Friedman, Peter Katz, Nick Ingwersen, Iip Rif’ai, Bondan Sikoki and Wayan Suriastini for their input into this study and the broader project. Financial support from the MacArthur Foundation (05-85158-000), the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (HD052762, HD051970), the National Institute on Aging (AG031266), and the National Science Foundation (CMS-0527763) is gratefully acknowledged.