Residential Wealth Distribution in Rio De Janeiro

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metrô + Ônibus De Integração

OLÁ, sabemos que muitas pessoas que participam do Simpósio de Pesquisa Sobre Migrações não conhecem muito bem a região e, por isso, algumas dúvidas podem surgir. Pensando nisso, montamos esse breve guia para te ajudar e para facilitar sua experiência tanto no Campus da Praia Vermelha da UFRJ quanto no Rio de Janeiro. SUMÁRIO 4 Transportes 9 Onde comer? 12 Pontos turísticos 22 Agenda cultural 30 Outras dicas 3 TRANSPORTE Separamos algumas das principais linhas de ônibus que circulam pela Zona Sul e que passam próximas ao Campus da Praia Vermelha. TRO 1 Sai da General Osório (Ipanema), passa pela UFRJ e vai para Central (via Av. Nossa Senhora de Copacabana/ Aterro do Flamengo). * TRO 2 Sai do Jardim de Alah (entre Leblon e Ipanema), passa pela UFRJ Campus Praia Vermelha e segue para rodoviária (via Lapa). * TRO 3 Sai do Leblon, passa pela UFRJ e segue para a Central (via Aterro / Avenida Nossa Senhora de Copacabana). * TRO 4 Sai da Vinicius de Moraes (Ipanema), vai até UFRJ Campus Praia Vermelha e segue para a rodoviária. * 4 TRO 5 Sai do Alto Gávea, passa pela UFRJ e vai para Central (Via Praia de Botafogo). * INT 1 Sai da Barra da Tijuca, mas também passa pelo Alto Leblon e Vieira Souto (Ipanema) e vai para UFRJ, tendo ponto final no Shopping Rio Sul (bem próximo do Campus). * INT 2 Sai da Barra da Tijuca, passa pela Vieira Souto (Ipanema), por Copacabana (Av Atlantida) e segue para a UFRJ, tendo ponto final no Shopping Rio Sul (bem próximo do Campus). * 415 Sai da Cupertino Durão (Leblon), vai para UFRJ e depois segue para o Centro (Central). -

Proposta De Restauração Do Fortim Santa Maria Da Barra. Salvador-Bahia

18º Encontro da Associação Nacional de Pesquisadores em Artes Plásticas Transversalidades nas Artes Visuais – 21 a 26/09/2009 - Salvador, Bahia PROPOSTA DE RESTAURAÇÃO DO FORTIM SANTA MARIA DA BARRA. SALVADOR-BAHIA Maria Herminia Olivera Hernández - UFBA* RESUMO: O Fortim Santa Maria da Barra, fortaleza construída no século XVII, constitui um dos monumentos tombados de caráter militar representativos do período colonial. O mesmo passou por modificações em sua estrutura e imagem visual quando lhe foram incorporados elementos, sobretudo na sua composição como conjunto arquitetônico construído. Através do presente artigo pretendemos aqui apontar os procedimentos metodológicos adotados para a realização do projeto que propõe junto à restauração do conjunto a inserção de novo uso: os escritórios da Fundação AVINA Brasil – Recursos Marinho, Costeiro e Hídricos. A dita instituição propõe promover ações de cunho social, ambiental e cultural, buscando transformar o Forte em um importante espaço educacional no país e no continente, principalmente em relação aos temas marinho-costeiros com os quais a história do Forte esta totalmente alinhada. Palavras-chave: Restauro. Arquitetura militar. Avina Brasil. ABSTRACT: The Fortim Santa Maria da Barra, fortress built in the seventeenth century, is one of the monuments of fallen military representative character of the colonial period. The same went for changes in its structure and visual image when it was incorporated elements, especially in its composition as set architectural built. In this article we want to point out here the methodological procedures adopted for the project which proposes to restore the set with the insertion of new use: the offices of the Foundation AVINA Brazil - Marine Resources, Coastal and Water. -

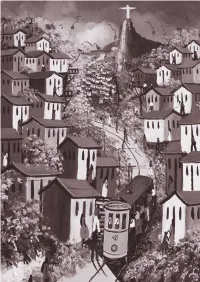

Duke University Dissertation Template

‘Christ the Redeemer Turns His Back on Us:’ Urban Black Struggle in Rio’s Baixada Fluminense by Stephanie Reist Department of Romance Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Walter Migolo, Supervisor ___________________________ Esther Gabara ___________________________ Gustavo Furtado ___________________________ John French ___________________________ Catherine Walsh ___________________________ Amanda Flaim Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 ABSTRACT ‘Christ the Redeemer Turns His Back on Us:’ Black Urban Struggle in Rio’s Baixada Fluminense By Stephanie Reist Department of Romance Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Walter Mignolo, Supervisor ___________________________ Esther Gabara ___________________________ Gustavo Furtado ___________________________ John French ___________________________ Catherine Walsh ___________________________ Amanda Flaim An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 Copyright by Stephanie Virginia Reist 2018 Abstract “Even Christ the Redeemer has turned his back to us” a young, Black female resident of the Baixada Fluminense told me. The 13 municipalities that make up this suburban periphery of -

Relação De Postos De Vacinação

SUBPAV/SVS COORDENAÇÃO DO PROGRAMA DE IMUNIZAÇÕES RELAÇÃO DE POSTOS DE VACINAÇÃO CAMPANHA NACIONAL DE VACINAÇÃO ANTI-INFLUENZA 2014 PERÍODO DE 22.04 A 09.05 (2a a 6a feira - SEMANA) N RA POSTO DE VACINAÇÃO ENDEREÇO BAIRRO 1 I CMS JOSÉ MESSIAS DO CARMO RUA WALDEMAR DUTRA 55 SANTO CRISTO 2 I CMS FERNANDO ANTONIO BRAGA LOPES RUA CARLOS SEIDL 1141 CAJÚ 3 II CMS OSWALDO CRUZ RUA HENRIQUE VALADARES 151 CENTRO 4 II CEVAA RUA EVARISTO DA VEIGA 16 CENTRO 5 II PSF LAPA RUA RIACHUELO 43 CENTRO 6 III CMS MARCOLINO CANDAU RUA LAURA DE ARAÚJO 36 CIDADE NOVA 7 III HOSPITAL MUNICIPAL SALLES NETTO PÇA. CONDESSA PAULO DE FRONTIN 52 ESTÁCIO 8 III HOSPITAL CENTRAL DA AERONAUTICA RUA BARÃO DE ITAPAGIBE 167 RIO COMPRIDO 9 III CF SÉRGIO VIEIRA DE MELLO AVENIDA 31 DE MARÇO S/Nº CATUMBI 10 III PSF TURANO RUA AURELIANO PORTUGAL 289 TURANO 11 VII CMS ERNESTO ZEFERINO TIBAU JR. AVENIDA DO EXÉRCITO 01 SÃO CRISTOVÃO 12 VII CF DONA ZICA RUA JOÃO RODRIGUES 43 MANGUEIRA 13 VII IBEX RUA FRANCISCO MANOEL 102 - TRIAGEM BENFICA 14 XXI UISMAV RUA BOM JESUS 40 PAQUETÁ 15 XXIII CMS ERNANI AGRÍCOLA RUA CONSTANTE JARDIM 06 SANTA TERESA 16 IV CMS DOM HELDER CAMARA RUA VOLUNTÁRIOS DA PATRIA, 136 BOTAFOGO 17 IV HOSPITAL ROCHA MAIA RUA GENERAL SEVERIANO, 91 BOTAFOGO 18 IV CMS MANOEL JOSE FERREIRA RUA SILVEIRA MARTINS, 161 CATETE 19 IV CMS SANTA MARTA RUA SÃO CLEMENTE, 312 BOTAFOGO 20 V CF PAVÃO PAVÃOZINHO CANTAGALO RUA SAINT ROMAN, 172 COPACABANA 21 V CMS CHAPEU MANGUEIRA E BABILONIA RUA SÃO FRANCISCO, 5 LEME 22 V CMS JOAO BARROS BARRETO RUA SIQUEIRA CAMPOS, S/Nº COPACABANA 23 VI -

Transformações Na Paisagem Urbana No Bairro Da Barra

DOI: https://doi.org/10.20396/rua.v24i2.8653878 A imagem da Barra, em Salvador, entre os séculos XVI e XXI The image of Barra, in Salvador, between the 16th and 21st centuries Márcia Maria Couto Mello1 https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2299-3117 Luan Britto Azevedo2 https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7964-9002 Lays Britto Azevedo3 https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3793-8399 Resumo O artigo tem por objetivo analisar a imagem do trecho que corresponde à Avenida Oceânica e à Avenida Sete de Setembro, na Barra, cidade de Salvador, Bahia, entre os séculos XVI e XXI, a partir da evolução da arquitetura, apontando permanências e modificações urbanas. Os procedimentos metodológicos basearam-se na pesquisa bibliográfica, documental e iconográfica, além da pesquisa de campo para a captura de imagens atuais que foram comparadas a imagens de outras épocas. Este estudo integra uma pesquisa que se desenvolve através do Grupo de Pesquisa Cidades, Urbanismo e Urbanidades, vinculado ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Desenvolvimento Regional e Urbano da Universidade Salvador (UNIFACS/Laureate International Universities), com o apoio do Programa de Iniciação Científica. Palavras-chave: Arquitetura; Urbanismo; Imagem da cidade; Transformação urbana. Abstract The objective of this article is to analyze the image of the stretch corresponding to Oceânica Avenue and Sete de Setembro Avenue at Barra neighborhood at Salvador city, state of Bahia, between the 16th and 21st centuries, from the evolution of architecture, pointing out permanences and urban modifications. The methodological procedures were based on bibliographical, documentary and iconographic research, as well as field research to capture current images that were compared to images from other times. -

CR12 Michaels.Pdf

Smile, You’re in Rio From the beach at Ipanema to the Favela of Rocinha, a host City braces for the 2016 Olympic Games By Julia Michaels y the time we came from São Paulo to live in Rio de Janeiro, in 1995, the grubby apartments we looked at boasted wheezing psychedelic orange refrigerators. BWe noticed that people’s cars were older than those in São Paulo, the metropolis to which banks and businesses and even the stock market had fled in the 1980s. Trees grew out of crumbling façades. “Buy an armored car,” advised our São Paulo friends, who thought we were crazy to move to a place at war with itself. Rio was divided between its informal and formal parts, between “hill” and “asphalt,” as the locals say. As the city developed, in the late nineteenth century, the poor were relegated to hills and swamps, to the shantytowns known here as favelas, with troublesome access both for people and infrastructure. Many favela residents worked for the upper classes, who happily squeezed into the South Zone flat areas between the hills and the ocean: Ipanema, Copacabana, and Leblon—names synonymous with Brazilian sun, surf, and sexiness. We did buy an armored car, and hired a driver to do our errands and escort our children to and from a private school. Drug traffickers were taking over huge swathes of the informal city—often the hilltop favelas—in both the North and South Zones. In West Zone favelas, inhabited largely by construction workers who’d come from drought-stricken northern Brazil, paramilitary groups ran things. -

United States Equity (USE3) Model Handbook

United States Equity Version 3 (E3) RISK MODEL HANDBOOK BARRA makes no warranty, express or implied, regarding the United States Equity Risk Model or any results to be obtained from the use of the United States Equity Risk Model. BARRA EXPRESSLY DISCLAIMS ALL WARRANTIES, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, REGARDING THE UNITED STATES EQUITY RISK MODEL, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO ALL IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY AND FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE OR USE OR THEIR EQUIVALENTS UNDER THE LAWS OF ANY JURISDICTION. Although BARRA intends to obtain information and data from sources it considers to be reasonably reliable, the accuracy and completeness of such information and data are not guaranteed and BARRA will not be subject to liability for any errors or omissions therein. Accordingly, such information and data, the United States Equity Risk Model, and their output are not warranted to be free from error. BARRA does not warrant that the United States Equity Risk Model will be free from unauthorized hidden programs introduced into the United States Equity Risk Model without BARRA's knowledge. Copyright BARRA, Inc. 1998. All rights reserved. 0111 O 02/98 Contents About BARRA . 1 A pioneer in risk management . 1 Introduction . 3 In this handbook. 3 Further references . 5 Books . 5 Section I: Theory 1. Why Risk is Important . 7 The goal of risk analysis. 8 2. Defining Risk . 11 Some basic definitions . .11 Risk measurement . 13 An example . 13 Risk reduction through diversification . 14 Drawbacks of simple risk calculations . 16 Evolution of concepts . 16 3. Modeling and Forecasting Risk . 21 What are MFMs? . -

Diccionario De Anglicismos Del Español Estadounidense 1

Diccionario de anglicismos del español estadounidense 1 Francisco Moreno-Fernández © Francisco Moreno-Fernández Diccionario de anglicismos del español estadounidense Informes del Observatorio / Observatorio Reports. 037-01/2018SP ISBN: 978-0-692-04726-2 doi: 10.15427/OR037-01/2018SP Instituto Cervantes at FAS - Harvard University © Instituto Cervantes at the Faculty of Arts and Sciences of Harvard University Advertencia previa Este diccionario no se presenta como una obra definitiva. La propia naturaleza de los datos aquí consignados, procedentes en gran parte de la lengua hablada, impide que un trabajo así se ofrezca en una versión cerrada. Antes bien, estas páginas se consideran materiales parciales de un proyecto en marcha, susceptibles de ser completados, actualizados y revisados en la medida en que los datos disponibles en cada momento lo hagan posible. En un futuro, este diccionario se presentará en línea, de modo que será más fácil la modificación continua de sus materiales. Por el momento, a modo de anticipo, se ha querido ofrecer una primera versión en papel para dar a conocer los primeros resultados del proyecto, de modo que se puedan hacer llegar a su autor todas las sugerencias, correcciones o informes que sean necesarios para mejorar la obra. Muchas gracias por cualquier tipo de ayuda o colaboración. 3 Prior Notice This dictionary is not intended as a final version. The very nature of the data reported here, derived largely from the spoken language, prevents such an effort from being presented in a closed version. Rather, these pages are considered partial materials of an ongoing project, to be completed, updated, and revised as new data becomes available. -

Case Study 13 Rio De Janeiro Building Exterior Moderate Industrial Pollution Exposure Low Coastal Salt Exposure

I M O A® INTERNATIONAL MOLYBDENUM ASSOCIATION Case Study 13 Rio de Janeiro Building Exterior Moderate Industrial Pollution Exposure Low Coastal Salt Exposure VIVO’s new headquarters in Rio de Janeiro was completed in 2005. The three-story This is especially true between May and September building (42,397 m2 or 456,357 ft2) was designed by the Brazilian architecture firm when high-pressure systems cause temperature Edo Rocha. inversions. Particulate levels are particularly high during this period and heavy rainstorms are infre- The company’s previously completed regional headquarters in São Paulo, Brazil also quent. This is the most corrosive period of the year. has a stainless steel exterior. The owners wanted to project a uniform corporate image. Both buildings were designed to suggest movement and to radiate techno - logy. Their exteriors reflect surrounding fragments of images and colors creating a kaleidoscope effect. Two different stainless steel finishes were used for the façade. The curved panels have a No.7 finish making them quite reflective. The flat panels have a No. 4 finish. The surface finishes have a maximum surface roughness of Ra 0.4 µm (16 µin). The building is in the Barra da Tijuca section of Rio de Janeiro, which has the second highest industrial and urban pollution level in the country. A mountain between this area and the coast prevents wind from carrying away air pollution. Figure B Close-up of the building exterior. Photo Courtesy of Núcleo Inox The building is about 3 km (1.9 miles) from the ocean. Generally, areas within 16 km (10 miles) of a large saltwater body are considered coastal. -

A Passionate Pacification: Sacrifice and Suffering in the Jesuit Missions of Northwestern New Spain, 1594 - 1767

A Passionate Pacification: Sacrifice and Suffering in the Jesuit Missions of Northwestern New Spain, 1594 - 1767 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Bayne, Brandon Lynn. 2012. A Passionate Pacification: Sacrifice and Suffering in the Jesuit Missions of Northwestern New Spain, 1594 - 1767. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard Divinity School. Citable link https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37367448 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA A Passionate Pacification: Sacrifice and Suffering in the Jesuit Missions of Northwestern New Spain, 1594 – 1767 A dissertation presented by Brandon L. Bayne to The Faculty of Harvard Divinity School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Theology in the subject of History of Christianity Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2012 © 2012 – Bayne, Brandon All rights reserved. iv Advisor: David D. Hall Author: Brandon L. Bayne ABSTRACT A Passionate Pacification: Sacrifice and Suffering in the Jesuit Missions of Northwestern New Spain, 1594 – 1767 This dissertation tracks Jesuit discourse about suffering in the missions of Northern New Spain from the arrival of the first missionaries in the 16th century until their expulsion in the 18th. The project asks why tales of persecution became so prevalent in these borderland contexts and describes how missionaries sanctified their own sacrifices as well as native suffering through martyrological idioms. -

Spurlock, R.S. (2012) the Laity and the Structure of the Catholic Church in Early Modern Scotland

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Enlighten: Publications Spurlock, R.S. (2012) The laity and the structure of the Catholic Church in early modern Scotland. In: Armstrong, R. and Ó hAnnracháin, T. (eds.) Insular Christianity. Alternative models of the Church in Britain and Ireland, c.1570–c.1700. Series: Politics, culture and society in early modern Britain . Manchester University Press, Manchester, UK, pp. 231-251. ISBN 9780719086984 Copyright © 2012 Manchester University Press A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge Content must not be changed in any way or reproduced in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder(s) When referring to this work, full bibliographic details must be given http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/84396/ Deposited on: 28 January 2014 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk . Insular Christianity Alternative models of the Church in Britain and Ireland, c.1570–c.1700 . Edited by ROBERT ARMSTRONG AND TADHG Ó HANNRACHÁIN Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave Macmillan Armstrong_OHannrachain_InsChrist.indd 3 20/06/2012 11:19 Copyright © Manchester University Press 2012 While copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in Manchester University Press, copyright in individual chapters belongs to their respective authors, and no chapter may be reproduced wholly -

003816-2 COMPLETO.Pdf

TH I Sfis-J Ie ne fay rien sans Gayeté (Montaigne, Des livres) Ex Libris José Mindlin ^SfiK PUBLICAÇÕES DA ACADEMIA BRASILEIRA II — HISTORIA CARTAS JESUITICAS II, CARTAS AVULSAS 1550 - 1568 An IMM0R-' ÍTALI TEM 19 3 1 OFFICINA•: INDUSTRIAL GRAPHICA EUA DA MISEEICORDIA, 74 ElO DE JANEIEO CARTAS AVULSAS BIBLIOTECA DE CULTURA NACIONAL (Publicações da Academia Brasileira) CLÁSSICOS BRASILEIROS I — LITERATURA Publicados: PROSOPOPÉA, de Bento Teixeira, 1923. PRIMEIRAS LETRAS (Cantos de Anchieta. O DIALOGO, de João de Léry. Trovas indijenas), 1923. MUSICA DO PARNASSO. —• A ILHA DE MARÉ — de Manuel Bo telho de Oliveira, 1929. OBRAS, de Gregorio de Mattos: I — Sacra, 1929 • II — IÃrica, 1923; III — Graciosa, 1930; IV — Satírico, 2 vols., 1930. DISCURSOS POLITICO-MORAIS, de Feliciano Joaquim de Sousa Nunes. A publicar-se: OBRAS, de Eusebio de Mattos. OBRAS, de Antônio de Sá. O PEREGRINO DA AMERICA, de Nuno Marques Pereira, 2 vols. a A SEMANA, de Machado de Assis (2 série). II — HISTORIA Publicados: TRATADO DA TERRA DO BRASIL. — HISTORIA DA PROVÍNCIA SAN TA CRUZ — de Pero de Magalhães Gandavo (notas de Rodolpho Garcia), 1924. HANS STADEN — VIAJEM AO BRASIL (revista e anotada por Theodoro Sampaio), 1930. DIÁLOGOS DAS GRANDEZAS DO BRASIL (notas de Rodolpho Gar cia), 1930. CARTAS DO BRASIL, de Manoel da Nobrega, (notas de Valle Cabral e R. Garcia), 1931. CARTAS AVULSAS DE JESUÍTAS (1550-1568). A publicar-se: INFORMAÇÕES, CARTAS, SERMÕES E FRAGMENTOS HISTÓRICOS, de Joseph de Anchieta. HISTORIA DOS COLLEGIOS JESUÍTAS DO BRASIL. TRATADO DESCRIPTIVO