A Survey of Communication Media Preferred by Smallholder Farmers in the Gweru District of Zimbabwe T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Budiriro Mumapurazi.Pmd

FCTZ A Better Life upenyu hwakanaka Impilo Enhle Mumapurazi Budiriro Mumapurazi Quarterly Newsletter March - May 2007 Celebrating 10 years of facilitating the empowerment of vulnerable groups in farm communities WHATS INSIDE Editorial…………………………………….....................…........................Pg - 1 Your letters……………………………………….............….....................….…Pg - 2 New hope for orphans in Chihwiti…………………….…………................….Pg - 3 More food despite poor rains-case study on conservation agriculture…Pg - 4 Old but going strong- story on goat pass on scheme……….….....………..Pg - 5 Widower gives away chickens to vulnerable groups……………….......…..Pg - 6 A man who has a passion for beekeeping………………..…… …….……….…..Pg - 7 Chawasarira nutrition garden bears fruit………….……………………………....Pg - 8 Smallholder farmer dedicated to community development…………...…pg - 9 Nyanzou garden source of livelihoods for many households………………Pg - 10 Chicken pass on project helpful- says beneficiary…………….…….....…..Pg - 11 Promoting household food security, Being HIV not disability- woman………………………………………...........….Pg - 12 income and sustainable livelihoods Children's Section……………………………….…..……………….……….............Pg - 14 Anniversary theme winner……………………………………………........………….Pg - 15 WELCOME MESSAGE EDITORIAL Welcome to the March-May 2007 issue of Budiriro Mumapurazi, Farm Community The Protracted Relief Programme (PRP) Trust of Zimbabwe (FCTZ’s) Quarterly with funding from the Department for Newsletter. This edition focuses on food security, sustainable livelihoods and HIV International Development (DFID) aims and AIDS. The newsletter will publish case to assist the poorest and most vulnerable studies on the impact of the FCTZ Sustainable Livelihoods Programme. households in Zimbabwe suffering from Testimonies on HIV and AIDS, which will the effects of rainfall failures, economic also feature in the newsletter, will inform readers on how farming communities are decline and the HIV and AIDS epidemic. copying with HIV and AIDS. -

ANALYSIS of SPATIAL PATTERNS of SETTLEMENT, INTERNAL MIGRATION, and WELFARE INEQUALITY in ZIMBABWE 1 Analysis of Spatial

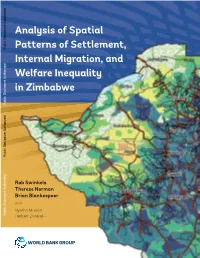

ANALYSIS OF SPATIAL PATTERNS OF SETTLEMENT, INTERNAL MIGRATION, AND WELFARE INEQUALITY IN ZIMBABWE 1 Analysis of Spatial Public Disclosure Authorized Patterns of Settlement, Internal Migration, and Welfare Inequality in Zimbabwe Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Rob Swinkels Therese Norman Brian Blankespoor WITH Nyasha Munditi Public Disclosure Authorized Herbert Zvirereh World Bank Group April 18, 2019 Based on ZIMSTAT data Zimbabwe District Map, 2012 Zimbabwe Altitude Map ii ANALYSIS OF SPATIAL PATTERNS OF SETTLEMENT, INTERNAL MIGRATION, AND WELFARE INEQUALITY IN ZIMBABWE TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii ABSTRACT v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ix ABBREVIATIONS xv 1. INTRODUCTION AND OBJECTIVES 1 2. SPATIAL ELEMENTS OF SETTLEMENT: WHERE DID PEOPLE LIVE IN 2012? 9 3. RECENT POPULATION MOVEMENTS 27 4. REASONS BEHIND THE SPATIAL SETTLEMENT PATTERN AND POPULATION MOVEMENTS 39 5. CONSEQUENCES OF THE POPULATION’S SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION 53 6. POLICY DISCUSSION 71 AREAS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH 81 REFERENCES 83 APPENDIX A. SUPPLEMENTAL MAPS AND CHARTS 87 APPENDIX B. RESULTS OF REGRESSION ANALYSIS 99 APPENDIX C. EXAMPLE OF LOCAL DEVELOPMENT INDEX 111 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report was prepared by a team led by Rob Swinkels, comprising Therese Norman and Brian Blankespoor. Important background work was conducted by Nyasha Munditi and Herbert Zvirereh. Wishy Chipiro provided valuable technical support. Overall guidance was provided by Andrew Dabalen, Ruth Hill, and Mukami Kariuki. Peer reviewers were Luc Christiaensen, Nagaraja Rao Harshadeep, Hans Hoogeveen, Kirsten Hommann, and Marko Kwaramba. Tawanda Chingozha commented on an earlier draft and shared the shapefiles of the Zimbabwe farmland use types. Yondela Silimela, Carli Bunding-Venter, Leslie Nii Odartey Mills, and Aiga Stokenberga provided inputs to the policy section. -

Original Research Article the Spatial Dimension of Health Service

Scholars Journal of Applied Medical Sciences (SJAMS) ISSN 2320-6691 (Online) Sch. J. App. Med. Sci., 2016; 4(1C):201-204 ISSN 2347-954X (Print) ©Scholars Academic and Scientific Publisher (An International Publisher for Academic and Scientific Resources) www.saspublisher.com Original Research Article The Spatial Dimension of Health Service Provision in Mashonaland West Province, Zimbabwe Takudzwa Mhandu, Dr Evans Chazireni Great Zimbabwe University, P O Box 1235, Masvingo, Zimbabwe *Corresponding author Dr Evans Chazireni Email: Abstract: Zimbabwe like many other developing countries has serious problems in its healthcare system. The quality of health service provision in Zimbabwe is generally poor Chazireni. Different parts of the country have serious healthcare problems. Mashonaland West, like other provinces in Zimbabwe, experiences numerous healthcare challenges. The research examines health service provision in Mashonaland West province in Zimbabwe. Data for this study was collected from ZIMSTAT published census reports and Ministry of health and Child Welfare published national health profiles. The analysis of the data was done through the composite index method. The calculated composite indices were used to rank the districts according to the level of health service provision. The researcher found out that there overall, the conditions of health service provision in Mashonaland West province is poor and that there are health service disparities among administrative districts in Mashonaland West province of Zimbabwe. There are many reasons which contribute to disparities in health care services at different levels (global, continental, regional, national and district level). It emerged from the research that the disparities are due to social, economic, physical and political factors. -

Annual Report 2016

ZIMBABWE NETWORK FOR HEALTH – EUROPE (ZimHealth) (RÉSEAU ZIMBABWÉEN POUR L’ACCÈS À LA SANTÉ) ANNUAL REPORT 2016 MARCH 2017 Chairperson’s Foreword This is the 9th year in the work of Zimbabwe Network for Health in its mission to support rehabilitation of public health facilities and sustain universal access and coverage with public health services based on our vision for better health for all Zimbabweans. This is my second year as chairman. I continue to provide institutional continuity required with changing ZimHealth executive. There has been need to proactively reach out to all Zimbabwean and friends of Zimbabwe who have very busy work and personal life but continue to participate in the work of the Executive, ZimHealth activities and events. In 2016, ZimHealth major project activities continued to focus on the US$1.2 million Mabvuku Polyclinic expansion in Harare City with the new construction occupation certificate provided in October 2016. This is being followed up with procurement and supply of medical equipment and recruitment and training of health staff to start theatre operations ZimHealth partnered with Ark Zimbabwe to support the rehabilitation of the floors and sluice rooms for the Mpilo Central Hospital maternity theatre and training of staff in infection control. The ZimHealth team continued to follow-up on the 24 ongoing projects with monitoring and evaluation visits to Zvamabande District Hospital-Shurugwi, Chinengundu Clinic-Chegutu, Nyamhunga Clinic - Kariba and Chikangwe Clinic- Karoi. New projects were jointly identified with Zimbabwe Association of Church Hospitals (ZACH) and some local authorities and government hospitals in 14 sites. Proposals have been developed and resource mobilization is underway. -

MAKONDE DISTRICT- Natural Farming Regions 14 February 2012

MAKONDE DISTRICT- Natural Farming Regions 14 February 2012 12 Locations Small Town Place of local Importance Mission 5 Mine Primary School ANGWA Angwa BRIDGE Clinic 3 Secondary School Health Facility 2 RUKOMECHI MANA POOLS NATIONAL Boundaries MASOKA PARK 4 Masoka MUSHUMBI Province Boundary Clinic POOLS CHEWORE MBIRE District Boundary & SAPI SAFARI AREA Ward Boundary 9 7 Transport Network 11 Major Road Secondary Road Feeder Road Connector Road ST. HURUNGWE CECELIA Track SAFARI AREA 16 Railway Line 10 Natural Farming Regions 8 1 - Specialized and diversified farming 2A - Intensive farming 2B - Intensive farming 3 - Semi-intensive farming Chundu Council 20 4 - Semi-extensive farming Clinic 8 DOMA Nyamakaze CHITINDIWA Nyama SAFARI 5 - Extensive farming Gvt Clinic Council AREA Protected Conservation Area Mashongwe SHAMROCKE 24 Council Clinic 3 Karuru 17 Council CHARARA (Construction) SAFARI VUTI AREA Dete Council Clinic RELATED FARMING SYSTEMS 9 KACHUTA 18 Region I - Specialized and Diversified Farming: Rainfall in this region is high (more than 1000mm per annum in areas lying below 1700m altitude, and more than 900mm 2 per annum at greater altitudes), normally with some precipitation in all months of the year. Kazangarare 4 Hewiyai Gvt Council Temperatures are normally comparatively low and the rainfall is consequently highly Council affective enabling afforestation, fruit and intensive livestock production to be practiced. Clinic 16 In frost-free areas plantation crops such as tea, coffee and macadamia nuts can be Lynx 1 grown, where the mean annual rainfall below 1400mm, supplementary irrigation of Clinic Private these plantation crops is required for top yields. LYNX Clinic HURUNGWE 1 23 GURUVE Region IIA - Intesive Farming : Rainfall is confined to summer and is moderately Kemutamba high (750-1000mm). -

ZIMBABWE Situation Report Last Updated: 26 Jun 2020

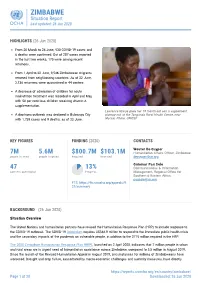

ZIMBABWE Situation Report Last updated: 26 Jun 2020 HIGHLIGHTS (26 Jun 2020) From 20 March to 24 June, 530 COVID-19 cases and 6 deaths were confirmed. Out of 207 cases reported in the last two weeks, 175 were among recent returnees. From 1 April to 22 June, 9,546 Zimbabwean migrants returned from neighbouring countries. As of 22 June, 2,136 returnees were quarantined in 44 centres . A decrease of admission of children for acute malnutrition treatment was recorded in April and May, with 50 per cent less children receiving vitamin A supplementation. Lawrance Njanje gives her 19-month-old son a supplement A diarrhoea outbreak was declared in Bulawayo City plumpy nut at the Tanganda Rural Health Centre, near with 1,739 cases and 9 deaths, as of 22 June. Mutare. Photo: UNICEF KEY FIGURES FUNDING (2020) CONTACTS Wouter De Cuyper 7M 5.6M $800.7M $103.1M Humanitarian Affairs Officer, Zimbabwe people in need people targeted Required Received [email protected] A S o r Guiomar Pau Sole 47 13% Communications & Information partners operational Progress Management, Regional Office for Southern & Eastern Africa [email protected] FTS: https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/9 21/summary BACKGROUND (26 Jun 2020) Situation Overview The United Nations and humanitarian partners have revised the Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP) to include response to the COVID-19 outbreak. The COVID-19 Addendum requires US$84.9 million to respond to the immediate public health crisis and the secondary impacts of the pandemic on vulnerable people, in addition to the $715 million required in the HRP. -

African Traditional Cultural Values and Beliefs: a Driving Force to Natural Resource Management: a Study of Makonde District, Mashonaland West Province, Zimbabwe

Journal of Culture, Society and Development www.iiste.org ISSN 2422-8400 An International Peer-reviewed Journal Vol.9, 2015 African Traditional Cultural Values and Beliefs: A Driving Force to Natural Resource Management: A Study of Makonde District, Mashonaland West Province, Zimbabwe Sigauke,E.I; Katsaruware,D. 2; Chiridza, P. 3; Saidi,T. 4 1. Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, Zimbabwe Open University, Mashonaland West Region, Chinhoyi. 2. Department of Agricultural Management; Zimbabwe Open University; Mashonaland West Region, Chinhoyi, Zimbabwe. 3. Department of Journalism and Media Studies; Zimbabwe Open University, Mashonaland West Region, Chinhoyi, Zimbabwe. 4. Department of Technology and Society Studies, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands. Abstract Natural resources in Africa are in jeopardy of depletion as a result of increasing demographic pressure and climate change. Sustainability of the natural resource base can be achieved through adoption of traditional cultural values and beliefs. This research was conducted in Makonde District, Mashonaland West Province of Zimbabwe. The research is qualitative in nature and employs the empirical case study research design through adopting the descriptive approach to data. The research involved description of knowledge, behaviors, perceptions and attitudes of the people in the Makonde District on cultural values and beliefs for the sustainable management of natural resources. The results of the study indicate that cultural norms and values such as totems, taboos, traditional ceremonies, and the formation of the old age group committees as well as the role of the spirit mediums have an impact of the conservation of natural resources namely tree species, water resources, forests, minerals and some sacred groves in Makonde district. -

Situation Report on Cholera in Zimbabwe Issue Number 10 21 January 2009

UNITED NATIONS NATIONS UNIES Office for the Coordination of Bureau de Coordination des Humanitarian Affairs des Affaires Humanitaires Zimbabwe OCHA Zimbabwe Situation Report on Cholera in Zimbabwe Issue Number 10 21 January 2009 Summary The Cholera outbreak has not yet been brought under control, as the number of cases continued to rise during the reporting period: • Cumulative number of reported cases in Zimbabwe since the beginning of the outbreak 48,623 • Number of reported deaths in Zimbabwe since the beginning of the outbreak 2,755 • Case fatality rate continues to rise to 5.7% against the target of less than 1% I. Situation analysis • Many Cholera Treatment centres still lack food, medicines, equipment and staff • UN agencies and INGOs report difficulties in providing support due to logistical difficulties Table 1: Cholera impacts by Province (21st January 2009). Province Cumulative Cumulative Case Fatality Community Deaths Community Deaths as Cases Deaths Rate (CFR) (%) (part of total) % of total Harare 12,326 572 4.6% 131 51.2% Mashonaland Central 2094 99 4.7% 82 82.8% Mashonaland East 4245 309 7.3% 193 62.5% Mashonaland West 11634 593 5.5% 306 47.4% Matabeleland North 416 36 9% 0 0% Matabeleland South 4556 150 3.3% 51 34% Manicaland 6064 393 6.5% 320 81.4% Masvingo 4876 403 8.3% 293 72.7% Bulawayo 407 14 3.4% 9 64.3% Midlands 2005 134 6.7% 108 80.6% Grand Total 48623 2755 5.7% 1655 60.1% Source: WHO/MoHCW Much higher figures have been reported this week than in previous weeks, which might be a result of gaps in previous reporting as figures are consolidated and forwarded to WHO. -

ZIM-Infographic-Flood-06 A4 07Feb2014 Zimbabwe Flash Flood - February 2014.Ai

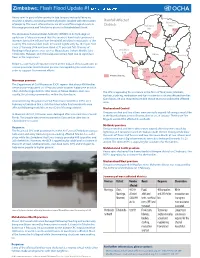

¡ ¢ £ ¤ ¥ ¦ § ¨ © ¡ ¥ Heavy rains in parts of the country in late January and early February resulted in deaths and displacement of people, coupled with destruction Rainfall A!ected Mashonaland of property. The worst a!ected areas are Chivi and Masvingo districts in Districts Mashonaland Central Masvingo province and Tsholotsho district in Matabeleland North. West Shamva The Zimbabwe National Water Authority (ZINWA) in its hydrological Makonde Binga update on 5 February warned that the country’s dam levels continue to Harare increase due to the in"ows from the rainfall activities in most parts of the Gokwe South country. The national dam levels increased signicantly by 10.29 per cent since 27 January 2014 and now stand at 71 per cent full. Chances of Mashonaland "ooding in "ood prone areas such as Muzarabani, Gokwe, Middle Sabi, Matabeleland East Tsholotsho, Malapati and Chikwalakwala remain high due to signicant North Midlands Manicaland "ows in the major rivers. Tsholotsho Gutu Bulawayo Below is a summary of reports received on the impact of incessant rains in Masvingo Chivi various provinces. Humanitarian partners are appealing for assistance in Matabeleland Masvingo order to support Government e!orts. Mangwe South A!ected districts Gwanda Mwenezi Chiredzi Masvingo province The Department of Civil Protection (DCP) reports that about 400 families needed to be evacuated on 3 February while another 4,000 were at risk in Chivi and Masvingo districts after levels at Tokwe-Mukorsi dam rose The CPC is appealing for assistance in the form of food, tents, blankets, rapidly, threatening communities within the dam basin. buckets, clothing, medication and fuel in order to assist the a!ected families. -

A ZIMBABWEAN = GOVERNMENT GAZETTE

a ZIMBABWEAN = GOVERNMENT GAZETTE Published by A uthority — ~ Vol. LXVII, No. 7 3rd FEBRUARY,1989 Price 40c General Notice 47 of 1989. (c) depart Masvingo Friday and Sunday 7.55 a.m., arrive Gweru £55 p.m. ; ROAD MOTOR TRANSPORTATION, ACT [CHAPTER 262] tert | The service to operate as follows— — Applications in Connexion with Road Service Permits (a) depart Gweru Monday to Thursday and Sunday 12 noon, arrive Masvingo 4.40 p.m.; . depart IN terms of subsection (4) of section 7 of ihe Road Motor (b) Gweru Friday 5 p.m., arrive Masvingo 9.40 p.m; () Gepart Masvingo Monday Transportation Act [Chapter 262], notice is hereby given that to Friday 3.35 a.m. arrive Gweru 8.15 the’ applications detailed in the Schedule, for the issue of a.m.; . amendment of roadservice permits, have been received for the (d) depart Masvingo Sunday 6 a.m., arrive Gweru 10.35 a.m. consideration of the Controller of Road Motor Transportation. must Any person wishing to object to any such application M. and A Special lodge with the Controller of Road Motor Transportation, Bus Services (Pvt.) Ltd. P.O. Box 8332, Causeway— _ OF 368/88, Permit: 22849, Motor-omnibus, Passenger-capacity: (a) a notice, in writing, of his intention to object, su as to ata, reach the Controller's office not Jater than the 24th Route: Bulawayo - Lupane - Benzies Bridge - Tshehelshebe - February, 1989; Ailen’ Wilson - Gomoza - Ndimimibili - Siakwa - Somtha- (b) his objection and the grounds therefor, on form R.M.T, nyvclo - Kana Mission. 24, together with two copies thereof. -

Health Problems in Zvimba Rural and Communal Areas in Zimbabwe

Developing Country Studies www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-607X (Paper) ISSN 2225-0565 (Online) DOI: 10.7176/DCS Vol.9, No.4, 2019 Health Problems in Zvimba Rural and Communal Areas in Zimbabwe Takudzwa Mhandu 1 Thandi F. Khumalo 2 Maxwell C.C. Musingafi 3* 1.Great Zimbabwe University, Department of Demography and Population Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences 2.University of Eswatini, Department of Sociology and Social Work, Faculty of Social Sciences 3.Zimbabwe Open University, Department of Development Studies, Faculty of Applied Social Sciences Abstract This study was carried out to determine people’s health problems in Zvimba district in Mashonaland West Province. The research employed the survey research design to solicit data since it was found to be the most appropriate for this study as it was capable of capturing the respondents’ views towards health issues in Zvimba district fast enough to meet both the time frame and the demands of the study. It involved 189 participants in an easily definable geographical area. These respondents comprised 135 communal dwellers who visited clinic or hospital the same day one of the researchers passed through the clinic or the hospital collecting data for the study, plus 54 professional health workers who accepted to participate in the study. The study used questionnaires and interviews for the collection of data. Research results showed that malaria and diarrhoea were the most prevalent diseases with the highest frequency rates among other diseases. The study recommends increase in the number of clinics, availability of low cost public transport, upgrade of road network links and community engagement in health awareness programmes. -

Zimbabwe-NAP-2019.Pdf

NATIONAL ACTION PLAN FOR ARTISANAL AND SMALL-SCALE GOLD MINING SECTOR IN ZIMBABWE in accordance with the Minamata Convention on Mercury November 2019 FOREWORD The environment cuts across all sectors of the economy, and society at large, directly or indirectly affecting by providing a range of goods and services. The use of natural resources and environment in general should not unduly impair the productive and assimilative or regenerative capacities of the environment. The Government is aware of socioeconomic benefits of ASGM activities and the associated impacts on the environment. ASGM. The need for development of a National Action Plan (NAP) for ASGM is a requirement under the Minamata Convention. It is designed to protect human health and the environment from anthropogenic emissions and/or releases of mercury and mercury compounds. The NAP allows the Government to be practical in dealing with mercury emissions while guided by baseline information of Mercury use practices in the ASGM Sector. The NAP development started in October 2016. Baseline information on mercury use practices was sought through field measurements and consultations with stakeholders and the public. Consultations were meant to canvas people’s perceptions on key issues to be addressed by the NAP and highlight what the Government should adopt. The NAP document fully and accurately reflects the interests, concerns and preferences of all key stakeholders on the issue of Mercury use, environmental degradation, and social vices associated with ASGM activities. It also recognises the pivotal role played by ASGM Sector in the economy. The overall thrust of NAP is to “reduce, where possible eliminate the use of mercury in the ASGM Sector”.