El C U Lt Iv O D E La Pa Pa En G U a T Em a La

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Potato Postharvest Processing Evaluation Report

Postharvest Processing Evaluation of Alaska Grown Potatoes A Specialty Crop Block Grant Project Introduction Potatoes have long been a staple produce of Alaskan agriculture. Between the years 2009-2016 Alaska growers have produced between 130,000 to 155,000 cwt annually amounting to over 2 million dollars in sales each year (2017 Alaska Annual Bulletin). There has been increasing interest in the use of Alaska Grown potatoes for processing in the local chipping and restaurant market, but this effort hasn’t been supported with data on the processing quality of our locally produced potatoes. To better meet the needs of the food service industries and to promote a growing market for producers, the Alaska Plant Materials Center (PMC) undertook a postharvest evaluation on our collection of potato varieties grown on site in Palmer, Alaska. The results of this research present timely and relevant data to Alaskan growers, processors and consumers. On a national level, the processing industry accounts for nearly 60% of potatoes produced annually. This trend has caused potato breeders to select for processing qualities, and quite a few processing cultivars have been recently registered and released for use. Although some of these newer varieties are grown here in Alaska, they have not been evaluated and compared to the data collected by growers in other regions or compared to established varieties that are known to do well here. Even if the physical qualities of the varieties were comparable to those grown elsewhere, Alaska is unlikely to compete in the national processing market because of our distance from any commercial processing facility and the small “family farm” scale of operation. -

2021 Alaska Certified Seed Potato Varieties

2021 Alaska Certified Seed Potato Varieties Variety Name Possible Other Names Potato Skin Color Potato Flesh Color Cooking/Eating Information Flower Description Yield Information Disease/Pest Information Adirondack Dark Blue (2) Dark Purple (2) Good roasted, steamed, and Petals are mainly Produces higher Can be susceptible to Blue in salads. Can be chipped, but white with some blue- yields than most common scab, silver scurf, not after being in cold storage. purple pigmentation. blue varieties. (1) and Colorado potato beetle. (1) (1) (1) Alaska AK Frostless Whitish/Yellowish White (3) Excellent flavor. (3) Good for Blue violet petals (3) Medium to high Somewhat resistant to Frostless (3) baking, chipping, and making yield potential. (3) common scab. Susceptible into french fries. Not good for to late blight, wart, and chipping after cold storage. (8) golden nematode. (3) Alaska Mountain Blush* Alaska Red AK Redeye Red (2) White (2) Good texture and flavor. Good Dark lilac petals. (9) High yielding. (9) Some susceptibility to scab. for boiling and baking, but not Susceptibility/resistance to good for chipping. (9) other diseases or pests is unknown. (9) Alby's Gold Yellow (2) Yellow (2) Texture is starchy. (2) Allegany Buff (10) Whitish-Yellowish Good for making french fries Light purple petals. High yielding. (10) Resistant to golden (10) and chipping, even after Yellow anthers. (10) nematode, early blight, and tubers are placed in cold verticillium wilt; some storage. Has good taste and resistance to pitted scab and texture after boiling and late blight. (10) baking. (11) Allagash Allagash Whitish/Yellowish White (3) Good Taste. -

Potato - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Potato - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Log in / create account Article Talk Read View source View history Our updated Terms of Use will become effective on May 25, 2012. Find out more. Main page Potato Contents From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Featured content Current events "Irish potato" redirects here. For the confectionery, see Irish potato candy. Random article For other uses, see Potato (disambiguation). Donate to Wikipedia The potato is a starchy, tuberous crop from the perennial Solanum tuberosum Interaction of the Solanaceae family (also known as the nightshades). The word potato may Potato Help refer to the plant itself as well as the edible tuber. In the region of the Andes, About Wikipedia there are some other closely related cultivated potato species. Potatoes were Community portal first introduced outside the Andes region four centuries ago, and have become Recent changes an integral part of much of the world's cuisine. It is the world's fourth-largest Contact Wikipedia food crop, following rice, wheat and maize.[1] Long-term storage of potatoes Toolbox requires specialised care in cold warehouses.[2] Print/export Wild potato species occur throughout the Americas, from the United States to [3] Uruguay. The potato was originally believed to have been domesticated Potato cultivars appear in a huge variety of [4] Languages independently in multiple locations, but later genetic testing of the wide variety colors, shapes, and sizes Afrikaans of cultivars and wild species proved a single origin for potatoes in the area -

![ML 2005 First Special Session, [Chap.__1__], Article __2__, Sec.[__11__], Subd. 7(I)____](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5558/ml-2005-first-special-session-chap-1-article-2-sec-11-subd-7-i-1085558.webp)

ML 2005 First Special Session, [Chap.__1__], Article __2__, Sec.[__11__], Subd. 7(I)____

2008 Project Abstract For the Period Ending June 30, 2010 PROJECT TITLE: Improving Water Quality on the Central Sands PROJECT MANAGER: John Moncrief and Carl Rosen AFFILIATION: University of Minnesota MAILING ADDRESS: University of MN, 1991 Upper Buford Circle, Dept. Soil, Water & Climate CITY/STATE/ZIP: St. Paul, MN 55108 PHONE: 612-625-2771 E-MAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: N/A FUNDING SOURCE: Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund LEGAL CITATION: ML 2005 First Special Session, [Chap.__1__], Article __2__, Sec.[__11__], Subd._7(i)____ Appropriation Language: As amended by ML 2008, Chap. 367, Sec. 2, Subd. 15 Carryforward APPROPRIATION AMOUNT: $587,000 Overall Project Outcome and Results Nitrate leaching to groundwater and phosphorus runoff to surface water are major concerns in sandy ecoregions in Minnesota. Some of these concerns can be attributed to agricultural crop management. This project was comprised of research, demonstration, and outreach to address strategies that can be used to minimize or reduce nitrate leaching and phosphorus runoff in agricultural settings. Research evaluating slowed nitrogen transformation products, nitrogen application timing, and nitrogen rates was conducted on potatoes, kidney beans, and corn under irrigation on sandy soils. For potatoes, variety response to nitrogen rate, source, and timing was also evaluated. Results showed several nitrogen management approaches reduced nitrate leaching while maintaining economic yields. Based on these results, promising treatments were demonstrated at a field scale using cost share monies. In some cases, producers tested or adopted new practices without the cost share incentive. • For potatoes, results show that at equivalent nitrogen rates, use of slow release nitrogen reduced nitrate leaching on average by 20 lb nitrogen per acre. -

Seed Potato Directory 2017

The farm operation grows 93 acres of field generations one and two seed, operates 4 greenhouses producing conventional and NFT minitubers. Our stewardship of this seed continues through WISCONSIN the certification Our of stewardship these seed oflots this on seed Wisconsin continues seed through grower t farms, there is no other program like it. CERTIFIED The program maintains variety trueness to type; selecting and testing clones, rogueing of weak, genetic variants, and diseased plants to continue to develop and maintain germplasm of your SEED POTATOES favorite varieties at our laboratory. 103 Years of Seed Growing Tradition A Century Long Tradition Pioneers In Seed Potato Certification Administered since inception by the College of Agricultural and Life Sciences, University of Wisconsin – Madison, the program Much of the early research work on potato diseases and how retains a full-time staff of experienced professionals to ensure they spread was done Scientists in Germany found and that, Holland through around careful the monitoring turn thoroughness and impartiality in inspection and certification of the century. Scientists found that, through careful monitoring procedures. o of the crop and removal of unhealthy plants, Similar they could research maintain soon was a vigorous, healthy stock indefinitely. Similar research soon was Through providing information, exercising technical skill, doing b being conducted in the United States. research directed at solving problems, and conducting outreach activities, the University meets the growers at the field level. USDA plant pathologist W.A. Orton had studied potato This special relationship to the academic community brings new certification in Germany and upon his return, began to work with T information on pathogens, best practices, and introduces high potato growers and Universities to introduce those concepts quality basic seed into the marketplace. -

2019 Potato Crop Year Research Reports

MINNESOTA AREA II POTATO RESEARCH AND PROMOTION COUNCIL AND NORTHERN PLAINS POTATO GROWERS ASSOCIATION 2020 RESEARCH REPORTS Table of Contents 3. Vine Desiccation as an Effective Disease Management Strategy to Control Verticillium Wilt of Potato N. Gudmestad 9. Evaluation of a Promising Minnesota Clone for N Response, Agronomic Traits & Storage Quality S. Gupta, J. Crants, M. McNearney & C. Rosen 16. Measuring Bruise Susceptibility Among New Fresh Market & Processing Varieties in Storage D. Haagenson 19. Baseline Evaluation of Pollinator Landscape Plantings Bordering Commercial Potato I.MacRae 25. Management of Colorado Potato Beetle in Minnesota & North Dakota I. MacRae 30. Managing PVY Vectors, 2019 I. MacRae 37. Carryover of Imazamox in Soil of Potato Fields A. Robinson 43. Evaluation of Fresh Potato Cultivars in the Field and Storage A. Robinson & D. Haagenson 46. Late Blight Spore Trapping Network for Minnesota A. Robinson & N. Gudmestad 52. ND Fresh Market Potato-Cultivar/Selection Trial Results for 2019 A. Robinson, E. Brandvik & P. Ihry 56. A Novel Approach to Manage Nitrogen Fertilizer for Potato Production Using Remote Sensing C. Rosen, J. Crants, M. McNearney & B. Bohman 65. Effects of Application Timing & Banded Versus Broadcast Application of ESN on Russet Burbank Potatoes C. Rosen, J. Crants & M. McNearney 79. Evaluation of Aspire, MicroEssentials S10 & MicroEssentials SZ as Sources of Potassium, Phosphate, Sulfur, Boron & Zinc for Russet Burbank Potatoes C. Rosen, J. Crants, & M. McNearney 87. Evaluation of Co-Granulated Formulation of K & B for Russet Burbank Potato Production C. Rosen, J. Crants & M. McNearney 94. Optimizing Planting Configuration, Planting Density, & N Rate for Russet Burbank Potato Production C. -

2004 Michigan Potato Research Report

MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATION IN COOPERATION WITH THE MICHIGAN POTATO INDUSTRY COMMISSION 2004 MICHIGAN POTATO RESEARCH REPORT Photo on Left Left to Right: Ben Kudwa, First Last, First Last, First Last, Senator Alan Cropsey, First Last, First Last Volume 36 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS……………………………. 1 2004 POTATO BREEDING AND GENETICS RESEARCH REPORT David S. Douches, J. Coombs, K. Zarka, S. Copper, L. Frank, J. Driscoll and E. Estelle…………………………………………. 5 2004 POTATO VARIETY EVALUATIONS D. S. Douches, J. Coombs, L. Frank, J. Driscoll, J. Estelle, K. Zarka, R. Hammerschmidt, and W. Kirk…………………..….……...… 18 MANAGEMENT PROFILE FOR NEW POTATO VARIETIES AND LINES DECEMBER 2004 Sieg S. Snapp, Chris M. Long, Dave S. Douches, and Kitty O’Neil…...….. 50 2004 ON-FARM POTATO VARIETY TRIALS Chris Long, Dr. Dave Douches, Fred Springborn (Montcalm), Dave Glenn (Presque Isle) and Dr. Doo-Hong Min (Upper Peninsula)..…... 56 SEED TREATMENT, IN-FURROW AND SEED PLUS FOLIAR TREATMENTS FOR CONTROL OF POTATO STEM CANKER AND BLACK SCURF, 2004 W.W. Kirk and R.L. Schafer and D. Berry, P. Wharton and P. Tumbalam………………………………..……...…………..………..... 70 POTATO SEED PIECE AND VARIETAL RESPONSE TO VARIABLE RATES OF GIBBRELLIC ACID 2003-2004 Chris Long and Dr. Willie Kirk……………..……...…………..……….... 73 MANAGING RHIZOCTONIA DISEASES OF POTATO WITH OPTIMIZED FUNGICIDE APPLICATIONS AND VARIETAL SUSCEPTIBILITY; RESULTS FROM THE FIELD EXPERIMENTS. Devan R. Berry, William W. Kirk, Phillip S. Wharton, Robert L. Schafer, and Pavani G. Tumbalam………………….……….... 78 HOST PLANT RESISTANCE AND REDUCED RATES AND FREQUENCIES OF FUNGICIDE APPLICATION TO CONTROL POTATO BLIGHT (COOPERATIVE TRIAL QUAD STATE GROUP 2004) W.W. -

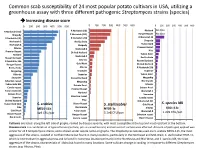

Common Scab Susceptibility of 24 Most Popular Potato Cultivars in USA, Utilizing a Greenhouse Assay with Three Different Pathoge

Common scab susceptibility of 24 most popular potato cultivars in USA, utilizing a greenhouse assay with three different pathogenic Streptomyces strains (species) Increasing disease score 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 Norland No data R Norkotah (ND) R Norkotah (ID) Shepody R Norkotah (ND) Ranger Russet No data R Norkotah (ID) R Norkotah 296 R Norkotah ID Norkotah 3 Red La Soda Shepody Yukon Gold Norkotah 8 Shepody Premier Russet Alturas Norkotah 8 Pike Premier Russet Dk Red Norland Norland Yukon Gold Norkotah 3 Russet Burbank Red La Soda Atlantic R Norkotah 296 Russet Burbank Ranger Russet Gold Rush Dk Red Norland Red La Soda Alturas R Norkotah 296 Megachip Snowden Superior Atlantic Superior Yukon Gold Snowden Russet Burbank Megachip Silverton russet Megachip Rio Grande Yukon Gold ME Dakota Pearl Atlantic Canela russet Dakota Pearl Premier Russet Yukon Gold (ID) Norkotah 3 Norland Dakota Pearl Snowden Silverton russet Superior Canela russet Dk Red Norland Pike R Norkotah ND Yukon Gold (WI) S. scabies Blazer Russet S. stelliscabiei Gold Rush S. species IdX Pike Rio Grande Alturas ME01-11h NY02-1c ID01-12c Gold Rush Yukon Gold 5.1e8 CFU/pot Norkotah 8 1.2e9 CFU/pot Blazer Russet 1e9 CFU/pot Ranger Russet Silverton russet Rio Grande Canela russet Blazer Russet Cultivars are listed along the left side of graphs, ranked by disease severity, with most susceptible at the top and most resistant at the bottom. Disease score is a combination of type of lesion (surface, pits or raised lesions) and amount of surface area affected. -

Potato Glossary

A Potato Glossary A Potato Glossary by Richard E. Tucker Last revised 15 Sep 2016 Copyright © 2016 by Richard E. Tucker Introduction This glossary has been prepared as a companion to A Potato Chronology. In that work, a self-imposed requirement to limit each entry to a single line forced the use of technical phrases, scientific words, jargon and terminology that may be unfamiliar to many, even to those in the potato business. It is hoped that this glossary will aid those using that chronology, and it is hoped that it may become a useful reference for anyone interested in learning more about potatoes, farming and gardening. There was a time, a century or more ago, when nearly everyone was familiar with farming life, the raising of potatoes in particular and the lingo of farming in general. They were farmers themselves, they had relatives who farmed, they knew someone who was a farmer, or they worked on a nearby farm during their youth. Then, nearly everyone grew potatoes in their gardens and sold the extra. But that was a long ago time. Now the general population is now separated from the farm by several generations. Only about 2 % of the US population lives on a farm and only a tiny few more even know anyone who lives on a farm. Words and phrases used by farmers in general and potato growers in particular are now unfamiliar to most Americans. Additionally, farming has become an increasingly complex and technical endeavor. Research on the cutting edge of science is leading to new production techniques, new handling practices, new varieties, new understanding of plant physiology, soil and pest ecology, and other advances too numerous to mention. -

Potato Tuber Viruses: Mop-Top Management A1777

NDSU EXTENSION NDSU EXTENSION EXTENDING KNOWLEDGEEXTENDING CHANGING KNOWLEDGE LIVES CHANGINGNDSU EXTENSION LIVES EXTENDING KNOWLEDGE CHANGING LIVES A1777 (Revised September 2018) Potato Tuber Viruses: Mop-top Management Andy Robinson Potato Extension Agronomist NDSU/University of Minnesota Department of Plant Sciences, NDSU Shashi K.R. Yellareddygari Research Scientist Department of Plant Pathology, NDSU Owusu Domfeh Student (former) Department of Plant Pathology, NDSU Neil Gudmestad University Distinguished Professor and Endowed Chair of Potato Pathology Department of Plant Pathology, NDSU The potato mop-top virus (PMTV) is spreading throughout the potato-growing regions in the U.S. This viral disease was con- firmed in Maine (2003), North Dakota (2010), Washington (2011), Idaho (2013), New Mexico (2015) and Colorado (2015). It also is found in production areas of Europe, South America and Asia. Figure 1. Tuber flesh exhibiting arcs, streaks and/or flecks Potato mop-top virus is seed- and soil-borne, and vectored when infected with mop-top virus. Flesh also may become by Spongospora subterranea f. sp. subterranea. It is the rust-colored or tinged with brown. (Owusu Domfeh) causal agent of powdery scab on potato. Once established in fields, powdery scab can survive for up to 18 years in the absence of a potato crop. Potato mop-top virus is of economic importance to potato growers throughout the U.S. because it may affect tuber quality and may be transferred from seed to daughter tubers. The potato mop-top virus is restricted primarily to the Solanaceae and Chenopodiaceae families. In addition to infested fields, PMTV has many other potential hosts, such as eastern black nightshade (Solanum ptycanthum), hairy nightshade (Solanum physalifolium), common lambsquarters (Chenpodium album) and sugar beets (Beta vulgaris). -

Potatoes in the Garden Dan Drost Vegetable Specialist Summary Potatoes Prefer a Sunny Location, Long Growing Season, and Fertile, Well-Drained Soil for Best Yields

Revised April 2020 Potatoes in the Garden Dan Drost Vegetable Specialist Summary Potatoes prefer a sunny location, long growing season, and fertile, well-drained soil for best yields. Plant potato seed pieces directly in the garden 14-21 days before the last frost date. For earlier maturity, plant potatoes through a black plastic mulch. Side dress with additional nitrogen fertilizer to help grow a large plant. Irrigation should be deep and frequent. Organic mulches help conserve water, reduce weeding, and keep the soil cool during tuber growth. Control insect and diseases throughout the year. Harvest potatoes as soon as tubers begin forming (new potatoes) or as they mature. Dig storage potatoes after the vines have died, cure them for 2-3 weeks, and then store the tubers in the dark at 40-45ºF. Recommended Varieties Potatoes are categorized by maturity class (early, mid-season or late), use (baking, frying, boiling), or tuber skin characteristics (russet, smooth, or colored). When selecting varieties, consider your growing environment, primary use, and how much space you have available to grow the plants. Most varieties grow well in Utah but all are not available. Most garden centers and nurseries carry varieties that produce high quality, productive seed tubers adapted to local conditions. Skin Type Suggested Varieties Russet Butte, Gem Russet, Ranger Russet, Russet Burbank Smooth Chipeta, Katahdin, Kennebec, Yukon Gold All Blue, Caribe (blue), Cranberry Red, Red Norland, Red Pontiac, Rose Finn, Colored Viking, How to Grow Soil: Potatoes prefer organic, rich, well-drained, sandy soil for best growth. Most soils in Utah will grow potatoes provided they are well drained and fertile. -

A Foodservice Guide to Fresh Potato Types POTATOES

THE PERFECT POTATO A Foodservice Guide to Fresh Potato Types POTATOES. THE PERFECT CANVAS FOR MENU INNOVATION. Potatoes aren’t just popular: they’re the #1 side dish in foodservice. You know that baked, mashed, roasted or fried, they have the remarkable ability to sell whatever you serve with them, enhancing presentations and adding value and appetite appeal. Now that you can tap into the intriguing shapes, colors and flavors of today’s exciting new potato types, innovation is easier than ever. No wonder so many chefs, from casual to fine dining, are reinventing potatoes in fresh new ways. So go ahead, grab a handful of potatoes and start thinking big. 1 A SPUD FOR ALL SEASONS AND REASONS. There are more than 4,000 potato varieties worldwide—though only a small fraction is commercialized. In the U.S., about 100 varieties are sold throughout the year to consistently meet the needs of the market. All of these varieties fit into one of five potato type categories: russet, red, white, yellow and specialty (including blue/purple, fingerling and petite). GET CREATIVE! We’ve created these at-a-glance potato type charts to help you find the right potato for any culinary purpose. Use them as a source of inspiration. Even when a potato type is recommended for a given application, another type may also work well to create a similar effect—or even a completely different, yet equally appealing result. Experiment with the types you have access to in new ways you haven’t tried. That’s the key to true menu innovation.