How Smart Cities Could Improve Open Data Portals to Empower Local Residents and Businesses: a Case Study of the City of Los Ange

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

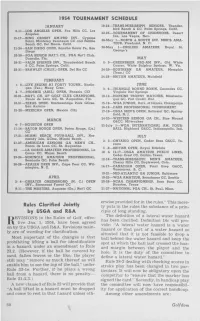

1954 TOURNAMENT SCHEDULE Rules Clarified Jointly by USGA and R&A

1954 TOURNAMENT SCHEDULE JANUARY 19-24—TRANS-MISSISSIPPI SENIORS, Thunder- bird Ranch & CC, Palm Springs, Calif. 8-11—LOS ANGELES OPEN, Fox Hills CC, Los Angeles 22-25—TOURNAMENT OF CHAMPIONS, Desert Inn, Las Vegas, Nev. 15-17—BING CROSBY AM-PRO INV., Cypress Point, Monterey Peninsula CC and Pebble 26-May 1-—NORTH & SOUTH INV. MEN'S AMA- Beach GC, Del Monte, Calif. TEUR, Pinehurst, N. C. 21-24—SAN DIEGO OPEN, Rancho Santa Fe, San 26-May 1—ENGLISH AMATEUR, Royal St. Diego George's 28-30—PGA SENIOR NAT'L CH., PGA Nat'l Club, Dunedin, Fla. MAY 28-31—PALM SPRINGS INV., Thunderbird Ranch 6- 9—GREENBRIER PRO-AM INV., Old White & CC, Palm Springs, Calif. Course, White Sulphur Springs, W. Va. 28-31—BRAWLEY (CALIF.) OPEN, Del Rio CC 24-29—SOUTHERN GA AMATEUR, Memphis (Tenn.) CC 24-29—BRITISH AMATEUR, Muirfield FEBRUARY 1- 6—LIFE BEGINS AT FORTY TOURN., Harlin- JUNE gen (Tex.) Muny Crse. 3- 6—TRIANGLE ROUND ROBIN, Cascades CC. 4- 7—PHOENIX (ARIZ.) OPEN, Phoenix CCi Virginia Hot Springs 16-21—NAT'L CH. OF GOLF CLUB CHAMPIONS, 10-12—HOPKINS TROPHY MATCHES, Mississau- Ponce de Leon GC, St. Augustine, Fla. gua GC, Port Credit, Ont. 18-21—TEXAS OPEN, Brackenridge Park GCrs®, 15-18—WGA JUNIOR, Univ. of Illinois, Champaign San Antonio 16-18—DAKS PROFESSIONAL TOURNAMENT 25-28—MEXICAN OPEN, Mexico City 17-19—USGA MEN S OPEN, Baltusrol GC, Spring- field, N. J. 24-25—WESTERN SENIOR GA CH., Blue Mound MARCH G&CC, Milwaukee 4- 7—HOUSTON OPEN 25-July 1—WGA INTERNATIONAL AM. -

(O) 617-794-9560 (M) [email protected]

Curriculum Vitae - Thomas W. Concannon, Ph.D. Page 1 of 17 THOMAS W. CONCANNON, PH.D. 20 Park Plaza, Suite 920, The RAND Corporation, Boston, MA 02116 617-338-2059 x8615 (o) 617-794-9560 (m) [email protected] CURRICULUM VITAE February 2021 ACADEMIC AND PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS AND ACTIVITIES APPOINTMENTS 2012-present Senior Policy Researcher, The RAND Corporation, Boston, Massachusetts 2006-present Assistant Professor, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston Massachusetts 2015-present Co-Director, Stakeholder and Community Engagement Programs, Tufts Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute Boston, Massachusetts 2012-2017 Associate Director, Comparative Effectiveness Research Programs, Tufts Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute Boston, Massachusetts 2009-2010 Visiting Professor, Institute for Social Research, School of Public Health, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California Teaching: Comparative effectiveness research 2004-2006 Pre-Doctoral Fellow, Institute for Clinical Research and Health Policy Studies, Tufts-New England Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts, 2002-2004 Research Analyst, Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, Dept. of Ambulatory Care and Prevention, Boston, Massachusetts. 1996-2001 Staff Consultant, John Snow, Inc., Boston, Massachusetts. 1992-1996 Client Services Director, North Shore AIDS Health Project, Gloucester, Massachusetts. TRAINING 2006 Doctor of Philosophy in Health Policy. Dissertation: A Cost and Outcomes Analysis of Emergency Transport, Inter-Hospital Transfer and Hospital Expansion in Cardiac Care Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 1991 Master of Arts in Political Science. Concentration: political theory McGill University, Montreal, PQ, Canada 1988 International Study in history and philosophy Universität Freiburg, Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany 1988 Bachelor of Arts in Political Science, cum laude. Concentration: political theory University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA Curriculum Vitae - Thomas W. -

1950-1959 Section History

A Chronicle of the Philadelphia Section PGA and its Members by Peter C. Trenham 1950 to 1959 Contents 1950 Ben Hogan won the U.S. Open at Merion and Henry Williams, Jr. was runner-up in the PGA Championship. 1951 Ben Hogan won the Masters and the U.S. Open before ending his eleven-year association with Hershey CC. 1952 Dave Douglas won twice on the PGA Tour while Henry Williams, Jr. and Al Besselink each won also. 1953 Al Besselink, Dave Douglas, Ed Oliver and Art Wall each won tournaments on the PGA Tour. 1954 Art Wall won at the Tournament of Champions and Dave Douglas won the Houston Open. 1955 Atlantic City hosted the PGA national meeting and the British Ryder Cup team practiced at Atlantic City CC. 1956 Mike Souchak won four times on the PGA Tour and Johnny Weitzel won a second straight Pennsylvania Open. 1957 Joe Zarhardt returned to the Section to win a Senior Open put on by Leo Fraser and the Atlantic City CC. 1958 Marty Lyons and Llanerch CC hosted the first PGA Championship contested at stroke play. 1959 Art Wall won the Masters, led the PGA Tour in money winnings and was named PGA Player of the Year. 1950 In early January Robert “Skee” Riegel announced that he was turning pro. Riegel who had grown up in east- ern Pennsylvania had won the U.S. Amateur in 1947 while living in California. He was now playing out of Tulsa, Oklahoma. At that time the PGA rules prohibited him from accepting any money on the PGA Tour for six months. -

1940-1949 Section History

A Chronicle of the Philadelphia Section PGA and its Members by Peter C. Trenham 1940 to 1949 Contents 1940 Hershey CC hosted the PGA and Section member Sam Snead lost in the finals to Byron Nelson. 1941 The Section hosted the 25 th anniversary dinner for the PGA of America and Dudley was elected president. 1942 Sam Snead won the PGA at Seaview and nine Section members qualified for the 32-man field. 1943 The Section raised money and built a golf course for the WW II wounded vets at Valley Forge General Hospital. 1944 The Section was now providing golf for five military medical hospitals in the Delaware Valley. 1945 Hogan, Snead and Nelson, won 29 of the 37 tournaments held on the PGA Tour that year. 1946 Ben Hogan won 12 events on the PGA Tour plus the PGA Championship. 1947 CC of York pro E.J. “ Dutch” Harrison won the Reading Open, plus two more tour titles. 1948 Marty Lyons was elected secretary of the PGA. Ben Hogan won the PGA Championship and the U.S. Open. 1949 In January Hogan won twice and then a collision with a bus in west Texas almost ended his life. 1940 The 1940s began with Ed Dudley, Philadelphia Country Club professional, in his sixth year as the Section president. The first vice-president and tournament chairman, Marty Lyons, agreed to host the Section Champion- ship for the fifth year in a row at the Llanerch Country Club. The British Open was canceled due to war in Europe. The third PGA Seniors’ Championship was held in mid January. -

Downtownla VISION PLAN

your downtownLA VISION PLAN This is a project for the Downtown Los Angeles Neighborhood Council with funding provided by the Southern California Association of Governments’ (SCAG) Compass Blueprint Program. Compass Blueprint assists Southern California cities and other organizations in evaluating planning options and stimulating development consistent with the region’s goals. Compass Blueprint tools support visioning efforts, infill analyses, economic and policy analyses, and marketing and communication programs. The preparation of this report has been financed in part through grant(s) from the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) through the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) in accordance with the provisions under the Metropolitan Planning Program as set forth in Section 104(f) of Title 23 of the U.S. Code. The contents of this report reflect the views of the author who is responsible for the facts and accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official views or policies of SCAG, DOT or the State of California. This report does not constitute a standard, specification or regulation. SCAG shall not be responsible for the City’s future use or adaptation of the report. 0CONTENTS 00. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 01. WHY IS DOWNTOWN IMPORTANT? 01a. It is the birthplace of Los Angeles 01b. All roads lead to Downtown 01c. It is the civic, cultural, and commercial heart of Los Angeles 02. WHAT HAS SHAPED DOWNTOWN? 02a. Significant milestones in Downtown’s development 02b. From pueblo to urban core 03. DOWNTOWN TODAY 03a. Recent development trends 03b. Public infrastructure initiatives 04. -

RAND Corporation, RR-708-DHHS, 2014

C O R P O R A T I O N The Effect of Eliminating the Affordable Care Act’s Tax Credits in Federally Facilitated Marketplaces Evan Saltzman, Christine Eibner ince its passage in 2010, the Patient Protection Key findings and Affordable Care Act (ACA) (Pub. L. 111- • Enrollment in the ACA-compliant individual S148, 2010) has sustained numerous legal chal- market, including plans sold in the market- lenges. Most notably, in Nat. Fedn. of Indep. Business places and those sold outside of the market- v. Sebelius (132 S. Ct. 2566, 2012), the U.S. Supreme places that comply with ACA regulations, Court upheld the individual-responsibility require- would decline by 9.6 million, or 70 percent, in ment to purchase health insurance under the federal federally facilitated marketplace (FFM) states. government’s taxing authority, but it made Medicaid • Unsubsidized premiums in the ACA-compliant expansion voluntary for states. The latest challenges individual market would increase 47 percent to the ACA focus on whether residents of states that in FFM states. This corresponds to a $1,610 have not established their own insurance exchanges are annual increase for a 40-year-old nonsmoker eligible for subsidies under 26 U.S.C. § 36B. Although purchasing a silver plan. 16 states1 and the District of Columbia have established their own exchanges, 34 states have not, instead defer- ring to the federal government to set up exchanges in their states. In its final rule, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) interpreted the provision as allowing tax credits to be made available for eligible people purchasing health insurance in state- based marketplaces (SBMs) or federally facilitated marketplaces (FFMs) (45 C.F.R. -

Official Media Guide

OFFICIAL MEDIA GUIDE OCTOBER 6-11, 2015 &$ " & "#"!" !"! %'"# Table of Contents The Presidents Cup Summary ................................................................. 2 Chris Kirk ...............................................................................52 Media Facts ..........................................................................................3-8 Matt Kuchar ..........................................................................53 Schedule of Events .............................................................................9-10 Phil Mickelson .......................................................................54 Acknowledgements ...............................................................................11 Patrick Reed ..........................................................................55 Glossary of Match-Play Terminology ..............................................12-13 Jordan Spieth ........................................................................56 1994 Teams and Results/Player Records........................................14-15 Jimmy Walker .......................................................................57 1996 Teams and Results/Player Records........................................16-17 Bubba Watson.......................................................................58 1998 Teams and Results/Player Records ......................................18-19 International Team Members ..................................................59-74 2000 Teams and Results/Player Records -

Multipliers and the Lechatelier Principle by Paul Milgrom January 2005

Multipliers and the LeChatelier Principle by Paul Milgrom January 2005 1. Introduction Those studying modern economies often puzzle about how small causes are amplified to cause disproportionately large effects. A leading example that emerged even before Samuelson began his professional career is the Keynesian multiplier, according to which a small increase in government spending can have a much larger effect on economic output. Before Samuelson’s LeChatelier principle, however, and the subsequent research that it inspired, the ways that multipliers arise in the economy had remained obscure. In Samuelson’s original formulation, the LeChatelier principle is a theorem of demand theory. It holds that, under certain conditions, fixing a consumer’s consumption of a good X reduces the elasticity of the consumer’s compensated demand for any other good Y. If there are multiple other goods, X1 through XN, then fixing each additional good further reduces the elasticity. When this conclusion applies, it can be significant both for economic policy and for guiding empirical work. On the policy side, for example, the principle tells us that in a wartime economy, with some goods rationed, the compensated demand for other goods will become less responsive to price changes. That changes the balance between the distributive and efficiency consequences of price changes, possibly favoring the choice of non-price instruments to manage wartime demand. For empirical researchers, the same principle suggests caution in interpreting certain demand studies. For example, empirical studies of consumers’ short-run responses to a gasoline price increase may underestimate their long response, since over the long 1 run more consumers will be free to change choices about other economic decisions, such as the car models they drive, commute-sharing arrangements, uses of public transportation, and so on. -

Rand Corporation Headquarters Building Final EIR Table of Contents

RAND CORPORATION HEADQUARTERS BUILDING Final Environmental Impact Report State Clearinghouse No. 1999122008 Prepared by: City of Santa Monica Planning & Community Development Department 1685 Main Street Santa Monica, CA 90407-2200 Contact: Mr. Andrew Agle Prepared with the assistance of: Rincon Consultants, Inc. 790 East Santa Clara Street Ventura, California 93001 August 2000 This report is printed on 50% recycled paper with 10% post-consumer content and chlorine-free virgin pulp. Rand Corporation Headquarters Building Final EIR Table of Contents Rand Corporation Headquarters Building Final EIR Table of Contents Page 1.0 Introduction................................................................................................................................... 1-1 2.0 Revisions to the Project Following Public Review 2.1 Revisions to the Project Description ............................................................................... 2-1 2.2 Clarifications to the EIR................................................................................................... 2-1 3.0 Correction Pages to the Draft EIR ............................................................................................... 3-1 4.0 Draft Environmental Impact Report ........................................................................................... 4-1 5.0 Comments and Responses 5.1 Comments and Responses .............................................................................................. 5-1 5.2 Commentors on the Draft EIR ....................................................................................... -

UCLA QUICK FACTS 2008-09 BRUINS 9 2008-09 Schedule

TABLE OF CONTENTS UCLA QUICK FACTS 2008-09 BRUINS 9 2008-09 Schedule .....................Inside Back Cover Address ............ J.D. Morgan Center, PO Box 24044 Season Outlook .......................................................2 Los Angeles, CA 90024-0044 Alphabetical Roster ................................................4 Athletics Phone ...................................(310) 825-8699 Portrait Roster .........................................................4 Ticket Offi ce.................................. (310) UCLA-WIN THE COACHING STAFF Chancellor ...........................................Dr. Gene Block Director of Athletics ..................Daniel G. Guerrero Head Coach Derek Freeman ................................5 Faculty Athletic Rep. ......................Donald Morrison Director of Operations Daniel Hour .................6 Enrollment .......................................................... 37,000 Undergraduate Assistant Coach Founded ................................................................. 1919 Brandon Christianson ............................6 Colors ....................................................Blue and Gold THE PLAYERS Nickname ............................................................ Bruins Conference.....................................................Pacifi c-10 Player Biographies ...................................................7 Conference Phone .................................925-932-4411 THE 2007-08 SEASON Conference Fax ......................................925-932-4601 National Affi -

Workplace Wellness Programs: Services Offered, Participation, And

Research Report Workplace Wellness Programs Services Offered, Participation, and Incentives Soeren Mattke, Kandice Kapinos, John P. Caloyeras, Erin Audrey Taylor, Benjamin Batorsky, Hangsheng Liu, Kristin R. Van Busum, Sydne Newberry Sponsored by the United States Department of Labor C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/rr724 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2014 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions.html. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface This Research Report was sponsored by the Employee Benefits Security Administration (EBSA) of the U.S. Department of Labor. -

Pgasrs2.Chp:Corel VENTURA

Senior PGA Championship RecordBernhard Langer BERNHARD LANGER Year Place Score To Par 1st 2nd 3rd 4th Money 2008 2 288 +8 71 71 70 76 $216,000.00 ELIGIBILITY CODE: 3, 8, 10, 20 2009 T-17 284 +4 68 70 73 73 $24,000.00 Totals: Strokes Avg To Par 1st 2nd 3rd 4th Money ê Birth Date: Aug. 27, 1957 572 71.50 +12 69.5 70.5 71.5 74.5 $240,000.00 ê Birthplace: Anhausen, Germany êLanger has participated in two championships, playing eight rounds of golf. He has finished in the Top-3 one time, the Top-5 one time, the ê Age: 52 Ht.: 5’ 9" Wt.: 155 Top-10 one time, and the Top-25 two times, making two cuts. Rounds ê Home: Boca Raton, Fla. in 60s: one; Rounds under par: one; Rounds at par: two; Rounds over par: five. ê Turned Professional: 1972 êLowest Championship Score: 68 Highest Championship Score: 76 ê Joined PGA Tour: 1984 ê PGA Tour Playoff Record: 1-2 ê Joined Champions Tour: 2007 2010 Champions Tour RecordBernhard Langer ê Champions Tour Playoff Record: 2-0 Tournament Place To Par Score 1st 2nd 3rd Money ê Mitsubishi Elec. T-9 -12 204 68 68 68 $58,500.00 Joined PGA European Tour: 1976 ACE Group Classic T-4 -8 208 73 66 69 $86,400.00 PGA European Tour Playoff Record:8-6-2 Allianz Champ. Win -17 199 67 65 67 $255,000.00 Playoff: Beat John Cook with a eagle on first extra hole PGA Tour Victories: 3 - 1985 Sea Pines Heritage Classic, Masters, Toshiba Classic T-17 -6 207 70 72 65 $22,057.50 1993 Masters Cap Cana Champ.