Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Länderinformationen Afghanistan Country

Staatendokumentation Country of Origin Information Afghanistan Country Report Security Situation (EN) from the COI-CMS Country of Origin Information – Content Management System Compiled on: 17.12.2020, version 3 This project was co-financed by the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund Disclaimer This product of the Country of Origin Information Department of the Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum was prepared in conformity with the standards adopted by the Advisory Council of the COI Department and the methodology developed by the COI Department. A Country of Origin Information - Content Management System (COI-CMS) entry is a COI product drawn up in conformity with COI standards to satisfy the requirements of immigration and asylum procedures (regional directorates, initial reception centres, Federal Administrative Court) based on research of existing, credible and primarily publicly accessible information. The content of the COI-CMS provides a general view of the situation with respect to relevant facts in countries of origin or in EU Member States, independent of any given individual case. The content of the COI-CMS includes working translations of foreign-language sources. The content of the COI-CMS is intended for use by the target audience in the institutions tasked with asylum and immigration matters. Section 5, para 5, last sentence of the Act on the Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum (BFA-G) applies to them, i.e. it is as such not part of the country of origin information accessible to the general public. However, it becomes accessible to the party in question by being used in proceedings (party’s right to be heard, use in the decision letter) and to the general public by being used in the decision. -

The ANSO Report (16-30 April 2012)

CONFIDENTIAL— NGO use only No copy, forward or sale © INSO 2012 Issue 96 REPORT 16‐30 April 2012 Index COUNTRY SUMMARY Central Region 1-3 The end of April maintained this year’s Despite these lower volumes, NGO expo- 4-11 Northern Region significant retraction in AOG activity levels sure to ambient violence was nonetheless Western Region 12-13 in comparison to the previous two years. highlighted by the series of eight direct in- Current volumes of AOG attacks (close cidents recorded this period. The responsi- Eastern Region 14-17 range, indirect fire, suicide) were down by ble actors’ profile remained consistent with 45% compared to the equivalent period in this year’s established trends, as 5 out of 8 Southern Region 18-21 2011 as well as by 19% below the volumes escalations were linked to crime whereas 22 ANSO Info Page for 2010 with this dynamic being primarily only 2 were initiated by AOG and one by driven by the decline in AOG attack vol- the security forces. In counter-point, the umes in the South. When compared to the territorial distribution denoted a significant HIGHLIGHTS first 4 months of 2011 (with 2012 data as shift as 5 cases occurred in the North, of the 25th of April) the January - April against only 2 in the East and 1 in the West Low incident volumes AOG incident volumes in Helmand are while none was recorded for Central this country-wide down by 78%, by 53% in Ghazni and by cycle. NGO exposure to ambi- 44% in Kandahar. In the East, compara- An NGO vaccination campaign member in ent criminality in the tive volumes are at par in Nangarhar but North Kunduz was killed during a residential rob- down by 22% and 48% in Kunar and bery attempt accounting for the second Khost respectively, which remain the two IED blast in NGO clinic in NGO fatality this year. -

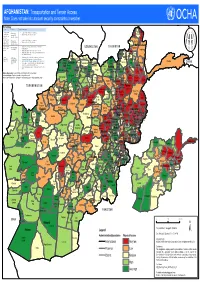

AFGHANISTAN: Transportation and Terrain Access Note: Does Not Take Into Account Security Constraints Or Weather

AFGHANISTAN: Transportation and Terrain Access Note: Does not take into account security constraints or weather. Methodology Indicator Data Sources Computation Methodology Density of road Length of road in kilometer per sqkm area Darwazbala Road network network in the Darwaz dataset (AIMS, Data normalized to 0 - 10 scale range district (all type Shaki Open Street Map) of roads) Density of major Length of road in kilometer per sqkm area Road network road networks Kuf Ab datasets (AIMS, Data normalized to 0 - 10 scale range (highway only) Open Street Map) Khwahan Badakhshan Airport or airfield Districts have been scored in a range of 0 – 10 based on Airport or airfield UZBEKISTAN TAJIKISTAN proximity of the following criteria Raghistan points (AIMS) Shighnan district District with airport or airfield inside district = score 10 Chah Yawan District with airport or airfield in the neighboring district = score 5 Other districts = score 0 Darqad Ab Yaftal Kohistan Kham Ab Sufla Terrain Terrain ruggedness index used as a measurement of terrain Shahri ASTER 30m Ruggedness Mangajek Qarqin Shortepa Dashti resolution Digital heterogeneity as described by Riley et al (1999) cited in Sharak Buzurg Fayzabad Ishkashiem Index (TRI) Khani Elevation Model http://119.92.145.181/fossgeo_build/qgis_terrain_analysis.html Imam Qala Wakhan The tool implemented in Raster Based Terrain Analysis plug-in Qurghan Mardyan Hairatan Kaldar Rustaq Argo Shahada CHINA (DEM) Chahar Jawzjan Dawlatabad Sahib Khwaja for QGIS was used in calculating TRI value. -

Afghanistan Flash Flood Situation Report2 1 May 2014 (Covering 24-30 April)

Afghanistan Flash Flood Situation Report2 1 May 2014 (covering 24-30 April) Situation Overview: Heavy rainfall between 24 and 30 April caused flash floods in ten northern, northeastern and western provinces. Initial reports obtained from provincial authorities indicate that 141 people have lost their lives and many others are still missing. In addition, the flooding has displaced more than 2,100 families and negatively impacted more than 9,000 families . The flooding also resulted in the destruction of public facilities, roads, and thousands of hectares of agricultural land and gardens. IOM, in close coordination with the Afghan National Disaster Management Authority (ANDMA) and Provincial Disaster Management Committee (PDMC) members, mobilized to the affected areas for rapid joint assessments in order to verify the emergency needs of the flood-hit communities. Based on the findings of these assessments, IOM and partners are carrying out interventions for the affected families. Northern Region: Jawzjan Province (UPDATE): An emergency PDMC meeting was convened on 25 April, and a crisis management team was established by government authorities to coordinate assessment and relief efforts. Several assessment teams, comprised of IOM, UN, I/NGO, and government representatives, were deployed to the affected areas. Initial information obtained from district authorities and from the joint assessment indicated that more than 3,700 families were severely affected, 2,100 families were displaced and 87 people reportedly killed in Khwaja Du Koh, Qush Tepa and Darzab districts. 1. Khwaja Du Koh District (UPDATE): A joint assessment team comprised of IOM, WHH, Save the Children, TearFund, PIN, Care International, ZOA, WFP, Action Aid and ANDMA mobilized to the affected area on 25 April and verified the exact number of displaced families with their needs. -

World Bank Document

AFGHANISTAN EDUCATION QUALITY IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM-II Public Disclosure Authorized MINISTRY OF EDUCATION PROCUREMENT PLAN FY2008-10-11 Public Disclosure Authorized Procurement Management Unit Education Quality Imrpovement Program-II Revised Procurement Plan EQUIP II (Revision Ref.: 04 on 15-05-10) General Public Disclosure Authorized 1 Project information: Education Quality Improvement Project II (EQUIP II) Country: Afghanistan Borrower: Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Project Name: Education Quality Improvement Project II (EQUIP II) Grant No.: H 354 –AF Project ID : P106259 P106259 Project Implementing Agency: Ministry of Education of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan 2 Bank’s approval date of the procurement Plan : 17 Nov.2007 (Original:) 3 Period covered by this procurement plan: One year Procurement for the proposed project would be carried out in accordance with the World Bank’s “Guidelines: Procurement Under IBRD Loans and IDA Credits” dated May 2004; and “Guidelines: Selection and Employment of Consultants by World Bank Borrowers” dated May 2004, and the provisions stipulated in the Legal Agreement. The procurement will be done through competitive bidding using the Bank’s Standard Bidding Documents (SBD). The general description of various items under different expenditure category are described. For each contract to Public Disclosure Authorized be financed by the Loan/Credit, the different procurement methods or consultant selection methods, estimated costs, prior review requirements, and time frame are agreed between the Recipient and the Bank project team in the Procurement Plan. The Procurement Plan will be updated at least annually or as required to reflect the actual project implementation needs and improvements in institutional capacity. II. Goods and Works and consulting services. -

DOWNLOAD PDF File

I love healthy stuff and junk an equal amount. “ www.outlookafghanistan.net “ Whatever I’m craving, I go for it. @The.Daily.Outlook.Afghanistan I’m never trying to lose weight - or gain it. [email protected] I’m just being. 0093 799-005019/ 777-005019 In front of Habibia High School, Quote of the Day Kelly Clarkson District 6, Kabul, Afghanistan Volume Num. 4540 Tuesday February, 09, 2021 Dalw, 21, 1399 www.Outlookafghanistan.net Price: 20/afs 200 Officials Miller Visits Suspected of American Troops Likely to NATO Base Embezzling Stay after May: US Senator in Herat COVID Funds WASHINGTON - US Senator Lind- sey Graham said Sunday night that American troops will stay on in Af- ghanistan and only leave when the conditions are right. In an interview with CBS News, Graham, a Republican senator, said: “I’m very pleased with what the Biden administration is proposing for Afghanistan. We’re going to keep troops there on a conditions-based approach.” KABUL - The Inspector General’s Office of Graham went on to state: “I think HERAT - US Army General Scott Miller, Afghanistan says that more than 200 gov- we’re not going to leave in May. Commander of the NATO-led Resolute ernment officials are suspected of being We’re going to leave when the condi- Support Mission (RS) in Afghanistan, vis- involved in embezzling COVID-19 funds. tions are right. ited the Western command center in Herat The office claims that 15 provincial gov- “The Taliban have been cheating. province Sunday where he met with for- ernors are also among those suspected of They haven’t been complying. -

AFGHANISTAN - Provinces & Districts Production Date : 30 August 2016 Administrative Map - August 2016

For Humanitarian purposes only AFGHANISTAN - Provinces & Districts Production date : 30 August 2016 Administrative map - August 2016 Darwaz Shaki Darwaz e Balla Kofab ² Khwahan Shighnan Raghestan Yangi Yawan Arghanjkhwa Darqad Qala Chahab Kohestan Khwaja Bahawuddin Shahr e Yaftal Qarqin Balkh Buzorg Khamyab e Sufla Shortepa Sharak e Kaldar Kunduz Dasht Fayzabad e Qala Hayratan Wakhan Khani Emam Char Dawlatabad saheb Rostaq Mardyan Argo Shuhada Qorghan Bagh Mingajik (Balkh) Khwaja Baharak Ghar (Badakhshan) Khwaja Jawzjan Dasht e Du Koh Archi Hazar Khash Nahr Qala sumuch Fayzabad Darayem Andkhoy e Shahi e Zal (Jawzjan) Charbulak Baharak Qaramqol Balkh Khulm Kalafgan Warduj Kunduz Takhar Keshm Khanaqah Mazar e Jorm Eshkashem Taloqan Sharif Teshkan Dehdadi Char Shiberghan darah Khanabad Aqcha Marmul Bangi Badakhshan Dawlatabad Chemtal Aliabad Chal Tagab Namakab Farkhar Feroz Hazrat e (keshm e Yamgan nakhchir Sultan bala) Zebak Charkent Eshkmesh Sholgareh Baghlan e Jadid Sar e Guzargahi Shirintagab Pul Qushtepa Aybak Burka Nur Sayad Fereng Gosfandi gharu Khwaja Sozmaqala Dara e Suf Warsaj Sabz Posh Samangan e Payin Khuram Pul e Maymana Darzab khumri Nahrin Khwaja Almar Keshendeh Sarbagh Hejran Khost Wa Bilcheragh Koran Faryab Fereng Monjan Zari Dahana e Ghori Barg e Sancharak Baghlan Matal Dehsalah Panjsher Ghormach Pashtunkot Ruy e Dara e Duab Qaysar Sar e Gurziwan Suf e Paryan Pul Bala Andarab Pul e Kohestanat Hesar Doshi Hes Mandol Murghab Khenjan e Awal Kamdesh Balkhab Kohestan Bazarak Kahmard (Faryab) Parun Tala Wa Shutul Muqur Onaba -

WASH Cluster Partners Presence Per District (As of June 2016)

AFGHANISTAN: WASH Cluster Partners Presence Per District (as of June 2016) D i a k r w a h a z S Darwazbala Kuf Ab Khwahan Raghistan Ya Shighnan wan b Darqad Chah Ab A Kohistan Yangi Qala m Qar Shahri Buzurg Arghanj Khaw a qin Sho Yaftal Sufla h rtepa S h K Sharak Hairatan Dashti Qala Fayzabad m Sahib a Q ldar Ima Ar h u Khani Chahar Bagh Ka Rustaq go a r Mangajek Dawlatabad Khwaja Ghar d Badakhshan gh Mardyan Baharak a Wakhan an Jawzjan al Dashte Archi W Z K D Khwaja Du Koh Chahar Bolak -I- Hazar Sumuch a Khash a Aqcha h y i ra r s d k la y Ishkashiem Andkhoy l a Kunduz h im u K Baharak ol d a Nahri Shahi Khulm Q Kunduz J j Qaramq a Taluqan i Khaniqa m u b B h Kalfagan rm a a Tashkan z B Takhar ra n y har Da a Marmul ha a an a Dihdadi Balkh C n F gh F al b g Namak Ab a r t a i Dawlatabad bi m Aliabad rk Tagab (Kishmi Bala) i i d h h B Chal h S C Feroz Nakhchir a a gh r Yamgan (Girwan) Zebak Chahar Kint Hazrati Sultan lan Sari Pul i J Ishkamish holgara ad Shirin Tagab S id B Aybak ur Guzargahi Nur Qush Tepa Sa ka n yy Farang Wa Gharu ja a n n Khwaja Sabz Posh d Dara-I-Sufi Payin Puli Khumri i u Faryab r Warsaj M A Darzab Sozma Qala Kishindih h a l Khuram Wa Sarbagh a m Samangan W a Maymana i r N G P Sangcharak r Khost Wa Firing an h a Bilchiragh a la ur o s Z a Dahann-i- Ghuri Ba h Gosfandi B Baghlan K rg r i i M m t f n at u Su A Dih Salah ya al a n Sari Pul - r K n an -I a c K ziw a Ruyi Du Ab d r P ur r h a h Qaysar o G a a is D i r i H n l t Dushi a Pu j b l a o Kamdesh Balkhab n d Kohistanat Panjsher n Parun Bala Murghab Kahmard a -

Afghanistan Health and Nutrition Sector Strategy 2007

1 Health & Nutrition Sector Strategy Prepared & submitted by: Ministry/Agency Name of Minister/Director Signature Ministry of Public Health H.E. The Minister, Dr. Said (MoPH) Mohammad Amin Fatimie Ministry of Agriculture, H.E. The Minister, Mr.Obaidullah Irrigation and Livestock Ramin (MAIL) Date of Submission 26 Feb 2008 3 ﺑﺴﻢ اﷲ اﻟﺮﺣﻤﻦ اﻟﺮﺣﯿﻢ In the name of Allah, the Most Merciful, the Most Compassionate Vision for Afghanistan By the solar year 1400 (2020), Afghanistan will be: . A stable Islamic constitutional democracy at peace with itself and its neighbors, standing with full dignity in the international family. A tolerant, united, and pluralist nation that honors its Islamic heritage and deep aspirations toward participation, justice, and equal rights for all. A society of hope and prosperity based on a strong, private sector-led market economy, social equity, and environmental sustainability. ANDS Goals for 1387-1391 (2008-2013) The Afghanistan National Development Strategy (ANDS) is a Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)-based plan that serves as Afghanistan’s Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (PRSP). It is underpinned by the principles, pillars and benchmarks of the Afghanistan Compact. The pillars and goals of the ANDS are: 1. Security: Achieve nationwide stabilization, strengthen law enforcement, and improve personal security for every Afghan. 2. Governance, Rule of Law and Human Rights: Strengthen democratic practice and institutions, human rights, the rule of law, delivery of public services and government accountability. 3. Economic and Social Development: Reduce poverty, ensure sustainable development through a private sector-led market economy, improve human development indicators, and make significant progress towards the Millennium Development Goals. -

WASH Cluster Partners Presence Per District (As of July 2017)

AFGHANISTAN: WASH Cluster Partners Presence Per District (as of July 2017) D i a a k r l w a a h a b z z S a w r a Kuf Ab D Khw ahan Raghistan C Ya Shighnan d h wa a a n q h b r a Kohistan A A D Yangi Qala b m Qar Shahri Buzurg a qin Khwaja Bahawuddin h Sh ortepa Yaftal Sufla Arghanj KhawS K Sharak Hairatan Dashti Qala h ib Fayzabad a Khani Chahar Bagh M Jawzjan n ar m Sah A h Q K a ya Kald Ima Rustaq rgo a u h ng rd d Badakhshan rg w a a Dawlatabad Khwaja Ghar a Wakhan h a je M Baharak a ja k I n Dashte Archi W s D D h u Hazar Sumuch K a Khash a Aqcha Qalay-I- Zal r k K i a r Chahar Bolak h s y d a Andkhoy o k K im u h l Nahri Shahi Khulm un Baharak h T j s d a h Qaramqol a Kunduz du K i Khaniqa a z Kalfagan m s B n h i b h qa e a l Talu k Jurm Mazari Sharif a a z u B n m ra n y rm ahar Da a a Dihdadi Ch a F a Balkh n Takhar l M b g F Shibirghan a i t a a Dawlatabad C Aliabad im d Chal rk Tagab (Kishmi Bala) h h B h C a Feroz NakhchirHazrati Sultan a a h gh Ish Namak Ab r Yamgan (Girwan) Zebak a lan kamis Sari Pul r i J h lgara K ad b Sho in id Shirin Taga G t B o in Aybak urk Guzargahi Nur Qush Tepa Sa s ay a n yy fa P Farang Wa Gharu a a n fi h j d u g n n Khwaja Sabz Posh d S rba i u Faryab k I- Sa r Warsaj P i - a Khwaja Hijran (Jilga Nahrin) M Sozma Qala a a W Puli Khumri h Darzab r Kishindih r m a Almar a a ura a s a D Kh Kho W h Maymana h i N st n t Bilchiragh c r Wa a G u a la i F r n g a ur irin u h n Z B h Baghlan g K B G ar o K a fi i- gi u n- A n Ma r o S S an n Dih Salah tal m t I- Samangan h d ya Sari Pul - Da a r a ra a -

(NABDP) 2011 Annual Report

United Nations Development Programme – Afghanistan NATIONAL AREA-BASED DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME (NABDP) 2011 Annual Report Collecting drinking water in Pad-e Nok Dari, Ab Kamari, Badghis Project ID: 00070832 (NIM) Duration: Phase III (July 2009 – June 2014) Strategic Plan Component: Promoting inclusive growth, gender equality, and achievement of the MDGs CPAP Component: Increased opportunities for income generation through promotion of diversified livelihoods, private sector development, and public private partnerships ANDS Component: Social and Economic Development Total Budget: $294,666,069 USD Responsible Agency: The Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation and Development Donors Acronyms ACEP Afghanistan Clean Energy Program AECID Agencia Espanola de Cooperation Internacional para el Desarrollo (Spain) AKF Aga Khan Foundation – Afghanistan AIRD Afghanistan Institute for Rural Development ANBP Afghanistan New Beginning Programme ANDS Afghanistan National Development Strategy ARDSS Agriculture and Rural Development Sector Strategy AREDP Afghanistan Rural Enterprise Development Programme BSC Business Support Center CDC Community Development Council CDP Community Development Plan CDRRP Comprehensive Disaster Risk Reduction Project CE Community Empowerment CIDA Canadian International Development Agency CLDD Community Led Development Directorate CNTF Counter Narcotic Trust Fund CIDA Canadian International Development Agency CPAP Country Program Action Plan DDA District Development Assembly DDP District Development Plan DIAG Disbandment of Illegal -

Women Economic Empowerment Rural Development Program

Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation and Development (MRRD) NEWSLETTER ISSUE# 27 January—2021 About WEERDP: IN THIS ISSUE: Women Economic Empowerment Rural Development Program (WEERDP), under leadership of Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation and Development (MRRD) and in view of National Unity Women’s handicraft exhibition held in Jawzjan province Government (NUG) goals and WEE-NPP objectives, was initiated in 2018 in continuation of 6 million AFN injected to SHGs & VSLAs in Khost province Afghanistan Rural Enterprise Development Program (AREDP) for the purpose of social and WEERDP formed SHGs &VSLAs in Urzgan province WEERDP/MRRD economic empowerment of women in rural areas of all 34 provinces of Afghanistan with the financial aid of World Bank. WEERDP and ASERD agreed on expanding cooperation Program’s activities progress in Kabul province Through this program Self Help Groups (SHG), Enterprise Groups (EG), Village Savings and WEERDP beneficiaries established a Literacy Training Center Loan Associations (VSLA) and Small and Medium Enterprises (SME) will be established to for women in Takhar province MAKING VILLAGES develop local economy, and create income generation and job opportunities for program more….. PRODUCTIVE beneficiaries (80% female) in rural areas of Afghanistan. WOMEN’S HANDICRAFT EXHIBITION تاسیس SHGS گروپTO های EDتولیدی در INJECT مرکز AFN وﻻیت پکتیا WEERDP FORMED SHGS &VSLAS IN 6 MILLION URUZGAN PROVINCE & VSLAS IN KHOST PROVINCE HELD IN JAWZJAN PROVINCE Women Economic Empowerment Rural Devel- Women Economic Empowerment