Pca Case No. 2013-09 in the Matter of an Arbitration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INDIA JANUARY 2018 – June 2020

SPACE RESEARCH IN INDIA JANUARY 2018 – June 2020 Presented to 43rd COSPAR Scientific Assembly, Sydney, Australia | Jan 28–Feb 4, 2021 SPACE RESEARCH IN INDIA January 2018 – June 2020 A Report of the Indian National Committee for Space Research (INCOSPAR) Indian National Science Academy (INSA) Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) For the 43rd COSPAR Scientific Assembly 28 January – 4 Febuary 2021 Sydney, Australia INDIAN SPACE RESEARCH ORGANISATION BENGALURU 2 Compiled and Edited by Mohammad Hasan Space Science Program Office ISRO HQ, Bengalure Enquiries to: Space Science Programme Office ISRO Headquarters Antariksh Bhavan, New BEL Road Bengaluru 560 231. Karnataka, India E-mail: [email protected] Cover Page Images: Upper: Colour composite picture of face-on spiral galaxy M 74 - from UVIT onboard AstroSat. Here blue colour represent image in far ultraviolet and green colour represent image in near ultraviolet.The spiral arms show the young stars that are copious emitters of ultraviolet light. Lower: Sarabhai crater as imaged by Terrain Mapping Camera-2 (TMC-2)onboard Chandrayaan-2 Orbiter.TMC-2 provides images (0.4μm to 0.85μm) at 5m spatial resolution 3 INDEX 4 FOREWORD PREFACE With great pleasure I introduce the report on Space Research in India, prepared for the 43rd COSPAR Scientific Assembly, 28 January – 4 February 2021, Sydney, Australia, by the Indian National Committee for Space Research (INCOSPAR), Indian National Science Academy (INSA), and Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO). The report gives an overview of the important accomplishments, achievements and research activities conducted in India in several areas of near- Earth space, Sun, Planetary science, and Astrophysics for the duration of two and half years (Jan 2018 – June 2020). -

Invitation New Proposal Under ISRO-JRP for the Year 2021-22

ISRO Proposal Format Application for grant of funds 1. Application Institution 2. Title of the Research Proposal 3. Name of the Principal Investigator 4. Name(s) of other investigator(s) with the name(s) of their Institution 5. Proposed duration of Research Project 6. Amount of grant requested (in Rs.) 1st Year 2nd Year Total Staff Equipment and Supplies Others Total 7. a) Bio-data of all the Investigators (Format-A). b) Brief description of the Research Proposal with details of budget (Format-B). c) Declaration (Format-C). 8. I/We have carefully read the terms and conditions for ISRO Research Grants and agree to abide by them. It is certified that if the research proposal is approved for financial support by ISRO, all basic facilities including administrative support available at our Institution and needed to execute the project will be extended to the Principal Investigator and other Investigators. Name Institution Designation Principal Investigator Co-Investigator(s) Head of the Department/Area Head of the Institution 1 Format A Bio-data of the Investigator(s)* 1. Name 2. Date of Birth (dd/mm/yyyy) 3. Designation 4. Degrees conferred (begin with Bachelor's degree) Degree Institution conferring the degree Field(s) Year 5. Research/training experience (in chronological order) Duration Institution Name of work done 6. Major scientific fields of Interest 7. List of publications 8. Email id and Telephone number of PI 9. Email id of the Head of the academic institution * Bio-data for all the investigators should be given, each on a separate sheet. 2 Format B Proposal Preparation Format 1. -

Research Areas in Space

RESPOND & AI Capacity Building Programme Office ISRO HQ, Bengaluru RESPOND & AI Capacity Building Programme Office ISRO HQ, Bengaluru RESEARCH AREAS IN SPACE A Document for Preparing Research Project Proposals RESPOND & AI Capacity Building Programme Office ISRO HQ, Bengaluru January 2021 Technical Guidance Dr. M A Paul, Associate Director, RESPOND & AI, ISRO HQ Technical Support and Compilation Smt Nirupama Tiwari, Sci/Engr SE, CBPO, ISRO HQ Shri K Mahesh, Sr. Asst, CBPO, ISRO HQ Technical Guidance Dr. M A Paul, Associate Director, RESPOND & AI, ISRO HQ For any queries please contact Director, Capacity Building Programme Office (CBPO) Technical Support and Compilation Indian Space Research Organisation HQ Smt Nirupama Tiwari, Sci/Engr SE, CBPO, ISRO HQ Department of Space Shri K Mahesh, Sr. Asst, CBPO, ISRO HQ Government of India Antariksh Bhavan New BEL Road For any queries please contact Bangalore 560094 E-mail: [email protected] Director, Capacity Building Programme Office (CBPO) Indian Space Research Organisation HQ Department of Space Associate Director, RESPOND & Academic Interface Government of India Indian Space Research Organisation HQ Antariksh Bhavan Department of Space New BEL Road Government of India Bangalore 560094 Antariksh Bhavan E-mail: [email protected] New BEL Road Bangalore 560094 Associate Director, RESPOND & Academic Interface E-mail: [email protected] Indian Space Research Organisation HQ Department of Space Government of India Antariksh Bhavan New BEL Road Bangalore 560094 E-mail: [email protected] CONTENTS -

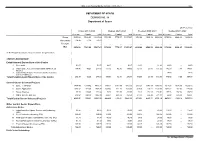

DEPARMENT of SPACE DEMAND NO. 94 Department of Space (In

Notes on Demands for Grants, 2021-2022 326 DEPARMENT OF SPACE DEMAND NO. 94 Department of Space (In ` crores) Actual 2019-2020 Budget 2020-2021 Revised 2020-2021 Budget 2021-2022 Revenue Capital Total Revenue Capital Total Revenue Capital Total Revenue Capital Total Gross 5851.08 7182.21 13033.29 5704.20 7775.27 13479.47 4954.68 4545.32 9500.00 5720.46 8228.63 13949.09 Recoveries -14.49 -1.19 -15.68 ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... Receipts ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... Net 5836.59 7181.02 13017.61 5704.20 7775.27 13479.47 4954.68 4545.32 9500.00 5720.46 8228.63 13949.09 A. The Budget allocations, net of recoveries, are given below: CENTRE'S EXPENDITURE Establishment Expenditure of the Centre 1. Secretariat 51.07 ... 51.07 36.17 ... 36.17 21.80 ... 21.80 26.50 ... 26.50 2. Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) Head 168.40 49.25 217.65 151.70 42.30 194.00 127.35 23.65 151.00 142.09 7.88 149.97 Quarters 3. Indian National Space Promotion and Authorization ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 10.00 ... 10.00 Centre (IN-SPACe) Total-Establishment Expenditure of the Centre 219.47 49.25 268.72 187.87 42.30 230.17 149.15 23.65 172.80 178.59 7.88 186.47 Central Sector Schemes/Projects 4. Space Technology 3498.49 5374.82 8873.31 3393.51 6367.99 9761.50 2991.07 3549.78 6540.85 3573.26 6676.90 10250.16 5. Space Applications 1070.02 724.95 1794.97 1097.80 712.20 1810.00 925.38 265.12 1190.50 1074.82 402.03 1476.85 6. -

Dr. K.Radhakrishnan's Speech Recipient of Doctor of Letters

23rd Convocation North Maharashtra University, Jalgaon Address By Dr. K. Radhakrishnan Formerly Chairman, Space Commission/ Secretary, Department of Space/ Chairman, ISRO March 16, 2015 23rd Convocation, North Maharashtra University, 2015 Prof V K Jain, Vice Chancellor, Doon University ( Uttarakhand State) Dehradun, Vice Chancellor of North Maharashtra University Prof. Sudhir U. Meshram; Deans of Faculties; Members of Board of College and University Development, Management Council, Academic Council, Senate and other Governing Bodies; Directors of the Schools; Registrar Prof A.M. Mahajan; Invited dignitaries; Staff Members of the University; Graduating Students and their Proud parents; Friends from the Media, Ladies and Gentlemen, 1. At the outset, I must say how deeply honoured I feel at having been invited to address this distinguished gathering on this auspicious occasion,marking the 23rdconvocation of this prestigious University. My best wishes to you all on this momentous occasion.I extend my hearty congratulation to all the graduating students for having achieved a landmark in their lives through excellent academic performance. At the same time, I commend the significant contribution of faculty members for imparting best training and guidance to the students with affectionate acumen. 2. This esteemed university provides an ideal atmosphere for pursuing research in diverse areas of science, arts, commerce and languages. Over the years, it has made a significant contribution in various areas of research and teaching, and continues to strive for excellence. 3. I understand, there are 220 affiliated colleges and four recognized Research Centres under the jurisdiction of North Maharashtra University. One can easily make out the educational spread of the University which encompasses the eight core Faculties, 13 Schools and one Institute contributing into the well structured educational framework. -

Annual Report (2016-17).Pdf

Annual Report 2016 - 2017 Citizens’ Charter Of Department Of Space Department of Space (DOS) has the primary responsibility of promoting the development of space science, technology and applications towards achieving self-reliance and facilitating in all round development of the nation. With this basic objective, DOS has evolved the following programmes: • Indian National Satellite (INSAT) programme for telecommunication, television broadcasting, meteorology, developmental education, societal applications such as telemedicine, tele-education, tele-advisories and similar such services • Indian Remote Sensing (IRS) satellite programme for the management of natural resources and various developmental projects across the country using space based imagery • Indigenous capability for the design and development of satellite and associated technologies for communications, navigation, remote sensing and space sciences • Design and development of launch vehicles for access to space and orbiting INSAT / GSAT, IRS and IRNSS satellites and space science missions • Research and development in space sciences and technologies as well as application programmes for national development The Department of Space is committed to: • Carrying out research and development in satellite and launch vehicle technology with a goal to achieve total self reliance • Provide national space infrastructure for telecommunications and broadcasting needs of the country • Provide satellite services required for weather forecasting, monitoring, etc. • Provide satellite imagery -

Space India 2.0 Commerce, Policy, Security and Governance Perspectives

Space India 2.0 Commerce, Policy, Security and Governance Perspectives Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan Narayan Prasad (Eds.) ISBN: 978-81-86818-28-2 Printed by: Mohit Enterprises © 2017 Observer Research Foundation. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from ORF. CONTENTS Foreword vii K Kasturirangan, former Chairman, ISRO Introduction xi Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan and Narayan Prasad I Space Commerce 1. Space 2.0 India: Leapfrogging Indian Space Commerce 1 Narayan Prasad 2. Traditional Space and NewSpace Industry in India: Current Outlook and Perspectives for the Future 11 Narayan Prasad 3. A Review of India’s Commercial Space Efforts 23 K R Sridhara Murthi 4. Exploring the Potential of Satellite Connectivity for Digital India 37 Neha Satak, Madhukara Putty, Prasad H L Bhat 5. Unlocking the Potential of Geospatial Data 51 Arup Dasgupta 6. Developing a Space Start-up Incubator to Build a NewSpace Ecosystem in India 71 Narayan Prasad 7. Electronic Propulsion & Launch Vehicles: Today and Beyond – An Indian Perspective 85 Rohan M Ganapathy, Arun Radhakrishnan and Yashas Karanam iv II Space Policy 8. Privatisation of Space in India and the Need for A Law 103 Kumar Abhijeet 9. SATCOM Policy: Bridging the Present and the Future 119 Ashok GV and Riddhi D’ Souza 10. A Review of India’s Geospatial Policy 141 Ranjana Kaul 11. Formation of PSLV Joint Venture: Legal Issues 151 Malay Adhikari 12. Exploring Space as an Instrument in India’s Foreign Policy & Diplomacy 165 Vidya Sagar Reddy III Space Security 13. -

Sponsored Research (RESPOND) Manual

Sponsored Research (RESPOND) Manual May 2016 Sponsored Research (RESPOND) and Space Technology Cell (STC) Projects Liquid Propulsion Systems Centre Sponsored Research (RESPOND) 1. Introduction The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) has evolved a programme through which financial support is provided for conducting research and development activities related to Space Science, Space Technology and Space Application to academia in India. This programme of Research Sponsored by ISRO is called RESPOND. In special cases research and development projects proposed by non-academic R & D laboratories can also be supported through this programme. The aim of RESPOND is to encourage quality research in areas of relevance to the Indian space programme. The primary objective of the Indian Space programme is to harness the advanced research areas of space science and technology for national development and to derive the maximum benefit for the people of India. The Indian Space Programme includes the following major elements: Demonstration of the feasibility of deriving from space science and technology- applications in space communications, long distance education, earth resources mapping/survey, meteorology and geodesy. Development of indigenous capability for design and development of orbiting satellites for scientific research and space applications, sounding rockets and satellite launch vehicles. RESPOND (Sponsored Research) programme started in the 1970s aims at encouraging academia to participate and contribute in various space related activities. Under RESPOND; projects are taken up by universities/academic institutions in the areas of relevance to Space Programme. Apart from this, ISRO has also set up Space Technology Cells at premiere institutions like Indian Institute of Technologies (IITs) - Bombay, Kanpur, Kharagpur& Madras; Indian Institute of Science (IISc), Bangalore and Joint Research Programme with University of Pune (UoP) to carry out research activities in the areas of space technology and applications. -

Research Areas of SAC

Cover Page Inner Page Research Areas of SAC A compendium of Topics for ISRO’s Sponsored Research: Soliciting proposals from Academia अंतरिक्ष उपयोग कᴂ द्र, इसिो, अहमदाबाद Space Applications Centre, ISRO, Ahmedabad October, 2020 FOREWORD Space Applications Centre is one of the major Centre of Indian Space Research Organisation. ‘Sponsored Research’ Programme started by ISRO in 1970s has come a long way as one of the flagship programme of ISRO with the primary objective of encouraging academia to participate and contribute in various space science and technology related research activities supporting the Indian Space Programme. ‘Sponsored Research’ program has also successfully established strong links with academic institutions to carry out quality R&D projects of relevance and derive useful deliverables to support ISRO’s various ongoing and future missions. The larger umbrella of this ambitious association with Academia across the country has also facilitated enhancing the academic base, nurturing the young researchers and developing various state-of-the art laboratory infrastructure to support R&D to meet the goals and objectives of ISRO. “Research Areas of SAC- A compendium of Topics for Sponsored Research” provide insights to the rich research diversity at the center being pursued through intellect and experience of Scientists and Engineers at SAC. Indeed, it’s a brilliant attempt for soliciting research proposals from academia across the country to contribute towards the various exciting facets of Space Technology Applications, Payloads systems, ground segment technology developments with absolute quality to meet the applications for national development and societal benefits. This eighth in the series of SAC document also encompasses recent and new research activities related to Space exploration through Space science and ISRO’s ambitious Human in Space mission. -

Respond Basket.Pdf

1 Introduction ISRO is embarking upon many new areas of Science and Technology by taking up challenging technological assignments incessantly. In this significant task of National Importance, ISRO is looking for wider participation and contributions from academia in a focused manner for timely accomplishment of its goals. In this regard, Capacity Building Programme Office of ISRO HQ has brought out a “RESPOND BASKET” comprising of around 150 urgent and most important research areas with a brief write up about the topic, for the participants to select and prepare detailed proposals on a priority basis. For each identified project under RESPOND Basket, a Co-Principal Investigator has been identified from the respective centre for any further clarification and coordination while preparing the proposals and during the tenure of the project. The projects have been identified ISRO/ DOS centre wise and the faculty/researcher may select a suitable topic/problem, prepare the proposal and submit to the concerned centre/unit for consideration. The proposals may be submitted to the Director of concerned centre as given in Annexure 1. For queries related to proposal, please contact our RESPOND co-ordinators at each centre (Annexure 2). The proposal submission formats and other necessary details are available in the ISRO website under the link www.isro.gov.in/research-and-academia-interface/submission-of- research-proposal. For any queries please contact: Director, Capacity Building Programme Office (CBPO) Indian Space Research Organisation HQ, Department -

Research Areas in Space

RESPOND & AI Capacity Building Programme Office ISRO HQ, Bengaluru RESPOND & AI Capacity Building Programme Office ISRO HQ, Bengaluru RESEARCH AREAS IN SPACE A Document for Preparing Research Project Proposals RESPOND & AI Capacity Building Programme Office ISRO HQ, Bengaluru November 2018 Technical Guidance and compilation Nirupama Tiwari, Sci/ Engr SE, CBPO M A Paul, Deputy Director, RESPOND & AI, CBPO For any queries please contact Director, Capacity Building Programme Office (CBPO) Indian Space Research Organisation HQ Department of Space Government of India Antariksh Bhavan New BEL Road Bangalore 560094 E-mail: [email protected] Deputy Director, RESPOND & Academic Interface Indian Space Research Organisation HQ Department of Space Government of India Antariksh Bhavan New BEL Road Bangalore 560094 E-mail: [email protected] preface I am extremely delighted to bring out the current edition of the Research Area Document. This comprehensive document is exclusively prepared to highlight the major programmes of ISRO and the current and upcoming Research and Development requirements. As you may be aware, ISRO is embarking upon many new areas of Science and Technology by taking up challenging technological assignments incessantly. In this important task of National Importance, ISRO is looking for wider participation and contributions from academia in a focused manner for timely accomplishments of its goals. In view of this, the concept of ISRO Academia day is brought out. The main aim behind this is to showcase the emerging research and development areas of ISRO, so that the faculty of the academic institutions can take up the research projects in the area of their specialization and expertise. -

Parliament of India Rajya Sabha

REPORT NO. 312 PARLIAMENT OF INDIA RAJYA SABHA DEPARTMENT-RELATED PARLIAMENTARY STANDING COMMITTEE ON SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY, ENVIRONMENT & FORESTS THREE HUNDRED TWELFTH REPORT DEMANDS FOR GRANTS (2018-2019) OF THE DEPARTMENT OF SPACE (DEMAND NO. 91) th (Presented to the Rajya Sabha on 13 March, 2018) (Laid on the Table of Lok Sabha on 13th March, 2018) (Presented to the Rajya Sabha on ______________, 2013) (Laid on the Table of Lok Sabha on _____________, 2013) Rajya Sabha Secretariat, New Delhi March, 2018, Phalguna, 1939 (Saka) Web site: http://rajyasabha.nic.in E-Mail : [email protected] Hindi version of this publication is also available PARLIAMENT OF INDIA RAJYA SABHA DEPARTMENT-RELATED PARLIAMENTARY STANDING COMMITTEE ON SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY, ENVIRONMENT & FORESTS THREE HUNDRED TWELFTH REPORT DEMANDS FOR GRANTS (2018-2019) OF THE DEPARTMENT OF SPACE (DEMAND NO. 91) (Presented to the Rajya Sabha on 13th March, 2018) (Laid on the Table of the Lok Sabha on 13th March, 2018) Rajya Sabha Secretariat, New Delhi March, 2018/ Phalguna, 1939 (Saka) C O N T E N T S PAGES 1. COMPOSITION OF THE COMMITTEE (i) 2. INTRODUCTION (ii) *3. ACRONYMS 4. REPORT *5. RECOMMENDATIONS/OBSERVATIONS-AT A GLANCE *6. MINUTES ___________________________________________ * To be appended at printing stage COMPOSITION OF THE COMMITTEE (2017-18) (Constituted on 1st September, 2017) ---------- 1. Shri Anand Sharma –– Chairman RAJYA SABHA 2. Shri Prasanna Acharya 3. Shri S.R. Balasubramoniyan 4. Shrimati Renuka Chowdhury 5. Shri Rajkumar Dhoot 6. Shri C.P. Narayanan 7. Shri Parimal Nathwani 8. Shri Sharad Pawar 9. Dr. T. Subbarami Reddy 10. Shri Bhupender Yadav LOK SABHA 11.