Download the Scanned

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

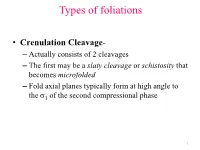

Actually Consists of 2 Cleavages

Types of foliations • Crenulation Cleavage- – Actually consists of 2 cleavages – The first may be a slaty cleavage or schistosity that becomes microfolded – Fold axial planes typically form at high angle to the σ1 of the second compressional phase 1 Progressive development (a → c) of a crenulation cleavage for both asymmetric (top) and symmetric (bottom) situations. From Spry (1969) Metamorphic Textures. Pergamon. Oxford. 2 Figure 23.24a. Symmetrical crenulation cleavages in amphibole-quartz-rich schist. Note concentration of quartz in hinge areas. From Borradaile et al. (1982) Atlas of Deformational and Metamorphic Rock Fabrics. Springer-Verlag. 3 Figure 23.24b. Asymmetric crenulation cleavages in mica-quartz-rich schist. Note horizontal compositional layering (relict bedding) and preferential dissolution of quartz from one limb of the folds. From Borradaile et al. (1982) Atlas of Deformational and Metamorphic Rock Fabrics. Springer-Verlag. 4 Figure 23.25. Stages in the development of crenulation cleavage as a function of temperature and intensity of the second deformation. From Passchier and Trouw (1996) Microtectonics. Springer-Verlag. Development of S2 micas depends upon T and the intensity of the second deformation 5 Types of lineations a. Preferred orientation of elongated mineral aggregates b. Preferred orientation of elongate minerals c. Lineation defined by platy minerals d. Fold axes (especially of crenulations) e. Intersecting planar elements. Figure 23.26. Types of fabric elements that define a lineation. From Turner and Weiss (1963) Structural 6 Analysis of Metamorphic Tectonites. McGraw Hill. Analysis of Deformed Rocks • If two or more geometric elements are present, we can add a numeric subscript to denote the chronological sequence in which they were developed and superimposed- • Deformational events: D1 D2 D3 … • Metamorphic events: M1 M2 M3 … • Foliations: So S1 S2 S3 … • Lineations: Lo L1 L2 L3 … • Plot on a metamorphism-deformation-time plot showing the crystallization of each mineral 7 Deformation vs. -

Megaliths and Geology: a Journey Through Monuments, Landscapes and Peoples

Megaliths and Geology Megálitos e Geologia MEGA-TALKS 2 19-20 November 2015 (Redondo, Portugal) Edited by Rui Boaventura, Rui Mataloto and André Pereira Access Archaeology aeopr ch es r s A A y c g c e o l s o s e A a r c Ah Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978-1-78969-641-7 ISBN 978-1-78969-642-4 (e-Pdf) © the individual authors and Archaeopress 2020 Financial support for the meeting Mega-Talks 2 has been provided by the project Moving megaliths in the Neolithic (PTDC/EPH-ARQ/3971/2012), funded by FCT (Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, Portugal) and the Municipality of Redondo (Portugal). All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com Contents Introduction: Megaliths and Geology: a journey through monuments, landscapes and peoples ........................... iii Moving megaliths in the Neolithic - a multi analytical case study of dolmens in Freixo-Redondo (Alentejo, Portugal). Rui Boaventura, Patrícia Moita, Jorge Pedro, Rui Mataloto, Luis Almeida, Pedro Nogueira, Jaime Máximo, André Pereira, José Francisco Santos & Sara Ribeiro ............................................................... 1 Funerary megalithism in the south of Beira Interior: architectures, spoils and cultural sequences. João Luís Cardoso .................................................................................................................................................................. 25 A look at Proença-a-Nova’s Megalithism (Beira Baixa Intermunicipal Community, UNESCO Global Geopark Naturtejo, Portugal). -

Metamorphism and the Origin of Granitic Rocks Northgate District Colorado

Metamorphism and the Origin of Granitic Rocks Northgate District Colorado GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 274-M Metamorphism and the Origin of Granitic Rocks Northgate District Colorado By T. A. STEVEN SHORTER CONTRIBUTIONS TO GENERAL GEOLOGY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 274-M A discussion of the progressive metamorphism, granitixation, and local rheomorphism of a layered sequence of rocks, and of the later emplacement and deuteric alteration of an unrelated granitic stock UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1957 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRED A. SEATON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. CONTENTS Page Page Abstract_________________________________ 335 Pre-Cambrian geology—Continued Introduction-_______________________________________ 335 Dacite porphyry—____ ——— __ —— _____________ 364 Acknowledgments__ ___--_____-____-_____-______-_ 336 Intrusive quartz monzonite_-____--_-__-_--_-_-_. 365 Geologic setting._______ — _________________________ 336 Petrography ________—— —— _______________ 365 Pre-Cambrian geology—___________________________ 337 Main body of the stock____________— 366 Hornblende gneiss___-_________-_-_____-________ 338 Marginal dikes_________-____-__-__——— 366 Quartz monzonite gneiss_________________________ 342 Satellitic dikes___-___.__________ 367 Biotite-garnet gneiss___________________________ 345 Wall-rock alteration_________ _ __——_ 368 Pegmatite_________________________________ -

Nucleation and Growth History in the Garnet Zone

Spear and Daniel Geological Materials Research v.1, n.1, p.1 Three-dimensional imaging of garnet porphyroblast sizes and chemical zoning: Nucleation and growth history in the garnet zone Frank S. Spear and Christopher G. Daniel Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, New York 12180 <[email protected]> (Received July 1, 1998; Published October 30, 1998) Abstract The three-dimensional (3-D) growth history of two garnet zone samples (Grt + Chl + Bt + Ms + Pl + Qtz + Ilm) from southwestern Maine was examined by serial sectioning and 3-D reconstructions of compositional zoning from backscatter images and X-ray maps. Mn, Fe, Mg, and Ca zoning is broadly concentric. The concentration of Mn in garnet cores generally correlates with size (d = 50 to 750 microns), indicating progressive nucleation. In detail, all elements show irregular, patchy zoning in the cores. Assuming constancy of Mn on the rims of all garnet crystals in a rock volume plus no subsequent diffusional modification, Mn concentration can be used as a Òtime lineÓ for garnet growth. Examination of the evolution of individual garnet crystals reveals that multiple nuclei formed simultaneously in the core regions and that nuclei expanded by growth in amoeba-shape forms along preexisting mineral grain boundaries (primarily quartz and plagioclase), dissolving the interior grains until the grains were either gone or encapsulated, at which time dissolution ceased. Amoeba-shaped garnet crystals coalesced as they grew and, simultaneously, new nuclei appeared in the nearby matrix. The net result was a single garnet porphyroblast that formed by the growth and coalescence of multiple nuclei. -

Petrologic Significance of Fe-Rich Staurolite in Pelitic Schists of the Silgará Formation, Santander Massif

EARTH SCIENCES RESEARCH JOURNAL Earth Sci. Res. J. Vol. 20, No. 1 (March, 2016): C1 - C7 PETROLOGY Petrologic significance of Fe-rich staurolite in pelitic schists of the Silgará Formation, Santander Massif Carlos Alberto Ríos R.1*, Oscar Mauricio Castellanos A.2 1*. Escuela de Geología, Universidad Industrial de Santander, Bucaramanga, Colombia, e-mail: [email protected] 2. Programa de Geología, Universidad de Pamplona, Colombia ABSTRACT Keywords: Staurolite, pelitic schists, Silgará Medium grade metapelites of the Silgará Formation at the Santander Massif (Colombian Andes) have been Formation, metamorphism, Santander Massif. affected by a medium-pressure/high-temperature Barrovian type of metamorphism, developing a sequence of metamorphic zones (biotite, garnet, staurolite and sillimanite). These rocks record a complex tectono- metamorphic evolution and reaction history. Metapelitic rocks from the staurolite zone are typically foliated, medium- to coarse-grained, pelitic to semipelitic schists that contain the mineral assemblage biotite + garnet + staurolite ± kyanite; all contain muscovite + quartz + plagioclase with minor K-feldspar, tourmaline, apatite, zircon, epidote, calcite, and Fe–Ti oxides. Field and microscopic evidences reveal that Fe-rich staurolite in pelitic schists is involved in several chemical reactions, which explains its formation and transformation to other minerals, which are very important to elucidate the reaction history of the Silgará Formation metapelites. Significado Petrológico de Estaurolita Rica en Fe en Esquistos Pelíticos de la Formación Silgará, Macizo de Santander RESUMEN Palabras clave: Estaurolita, esquistos pelíticos, Medium grade metapelites of the Silgará Formation en el Macizo de Santander (Andes Colombianos) han sido Formación Silgará, metamorfismo, Macizo de afectadas por un metamorfismo de tipo Barroviense, el cual se ha producido en condiciones de media presión y Santander. -

A Sillimanite Gneiss Dome in the Yukon Crystalline Terrane, East-Central Alaska: Petrography and Garnet- Biotite Geothermometry

PROPERTY OF DUG,r c LiiiRARYyw A Sillimanite Gneiss Dome in the Yukon Crystalline Terrane, East-Central Alaska: Petrography and Garnet- Biotite Geothermometry By CYNTHIA DUSEL-BACON and HELEN L. FOSTER SHORTER CONTRIBUTIONS TO GENERAL GEOLOGY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1170-E Petrographic, geothermometric, and structural data are used to support the hypothesis that a 600-km* area of pelitic metamorphic rocks is a gneiss dome -- -- UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1983 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR JAMES G. WATT, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Dusel-Bacon. Cynthia. A sillimanite gneiss dome in the Yukon crystalline terrane, eastcentral Alaska. (Shorter contributions to general geology) (Geological Survey Professional Paper 1170-E) Bibliography Supt. of Docs. no.: 1 19.412: 1170-E 1. Gneiss--Alaska. 2. Intrusions (Geology)-Alaska. I. Foster, Helen Laura. 1919- . 11. Title. Ill. Series. IV. Series: United States: Geological Survey. Professional Paper 1170-E. QE475.G55D87 1983 552'.4 83-60003 1 For sale by the Distribution Branch, U.S. Geological Survey, 604 South Pickett Street, Alexandria, VA 42304 CONTENTS Page Abstract .............................................................................................................................................................. El Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................... -

A Partial Glossary of Spanish Geological Terms Exclusive of Most Cognates

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY A Partial Glossary of Spanish Geological Terms Exclusive of Most Cognates by Keith R. Long Open-File Report 91-0579 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards or with the North American Stratigraphic Code. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. 1991 Preface In recent years, almost all countries in Latin America have adopted democratic political systems and liberal economic policies. The resulting favorable investment climate has spurred a new wave of North American investment in Latin American mineral resources and has improved cooperation between geoscience organizations on both continents. The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) has responded to the new situation through cooperative mineral resource investigations with a number of countries in Latin America. These activities are now being coordinated by the USGS's Center for Inter-American Mineral Resource Investigations (CIMRI), recently established in Tucson, Arizona. In the course of CIMRI's work, we have found a need for a compilation of Spanish geological and mining terminology that goes beyond the few Spanish-English geological dictionaries available. Even geologists who are fluent in Spanish often encounter local terminology oijerga that is unfamiliar. These terms, which have grown out of five centuries of mining tradition in Latin America, and frequently draw on native languages, usually cannot be found in standard dictionaries. There are, of course, many geological terms which can be recognized even by geologists who speak little or no Spanish. -

Some New Textural Criteria from Pelitic Hornfels--A Comment

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS MINERALOGICAL MAGAZINE~ SEPTEMBER I976, VOL. 4 O, PP. 787-8 Porphyroblastesis and displacement: some new textural criteria from pelitic hornfels--a comment S A G G ER SON (I974) has described the deflection of matrix S-surfaces around porphy- roblasts in a hornfels from near Penge, Transvaal. He has interpreted these micro- structures as being due to replacement and displacement of the matrix by the growing porphyroblasts. He has also reported an order of crystallization of the porphyroblastic minerals. We present alternative explanations for both these aspects. Displacement versus deformation: (i) Saggerson has assumed that no deformation resulted either from the 'regional tilting and local disturbances associated with faulting' (Saggerson, 1974, p. 793), or from the thermal metamorphism itself. A small bulk strain (as little as I ~o) involving elongation in the direction of the original sedimentary lamination could produce much higher strains around local heterogenei- ties, such as porphyroblasts, porphyroblast coigns (p. 795), and areas between two close porphyroblasts (pp. 795, 796) The existence of such a small bulk strain would be difficult to disprove, and could explain all the deflection microstructures observed. Saggerson argued that the matrix deflections around porphyroblasts are not tectonic because 'disturbance is rarely symmetrical and not necessarily in the same sense' (P. 795)- However, this argument assumes a simple relationship between external forces and microscopic strains--a most unlikely situation in such heterogeneous rocks. (2) Even if no bulk deformation of the rock has been imposed externally, two inter- nal processes may lead to local strains: volume changes between solid reactants and products in the porphyroblast-producing reactions; and bulk volume change due to thermal expansion of the metamorphic aureole as it was heated to a higher tempera- ture than the confining rocks further away from the intrusion; if relaxation of this expansion were not equal in all directions, internal deformation may have resulted. -

Preferred Orientations of Garnet Porphyroblasts Reveal Previously Cryptic Templating During Nucleation Alexandra B

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Preferred orientations of garnet porphyroblasts reveal previously cryptic templating during nucleation Alexandra B. Nagurney1*, Mark J. Caddick1, David R. M. Pattison2 & F. Marc Michel1 Electron back scattered difraction data of garnet crystals from the Nelson Aureole, British Columbia and the Mosher’s Island formation, Nova Scotia, reveals that 22 garnet crystals are all oriented with one of three crystal directions parallel to the trace of the foliation plane in thin section. Structural models suggest that these relationships are due to preferential garnet nucleation onto muscovite, with the alignment of repeating rows of Al octahedra and Si tetrahedra in each leading to inheritance of garnet orientation from the muscovite. These results highlight that epitaxial nucleation may be a prevalent process by which porphyroblast minerals nucleate during metamorphism and carry implications for the role that non-classic nucleation pathways play in the crystallization of metamorphic minerals, the distribution of porphyroblasts in metamorphic rocks, and, in cases in which nucleation is the rate limiting step for crystallization, the energetics of metamorphic reactions. Deciphering the mechanisms of mineral crystallization has important implications for understanding many geologic processes. Classical theory states that nucleation and growth are each a single step process based on monomer-by-monomer addition of simple chemical species1. However, this model may not be appropriate for many geologic systems, and minerals may crystallize via multi-step non-classical pathways, such as the formation of intermediate nanocrystals, amorphous nanoparticles, or via nucleation on a substrate2. Two common examples of non-classical nucleation pathways are epitaxy, which is when a phase overgrows a substrate, and topotaxy, in which a reactant phase is converted into a new product phase that utilizes part of the precursor structure3. -

TEXTURES of IGNEOUS ROCKS Today, Geologist Working With

TEXTURES OF IGNEOUS ROCKS Today, Geologist working with igneous rocks has to apply a wide range of skills, including the analysis of field relationships, hand – specimen identification in the field, description and interpretation of thin sections, the quantitative interpretation of rock and mineral analyses, the interpretation of experimental equilibria, phase diagrams and structures and textures of igneous rocks. Therefore textures of igneous rocks play a significant role in determining the identification of rocks. The other factors involved are: The diffusion rate - the rate at which atoms or molecules can move (diffuse) through the liquid. The rate of nucleation of new crystals - the rate at which sufficient chemical constituents of a crystal can come together in one place without dissolving. The rate of growth of crystals - the rate at which new constituents can arrive at the surface of the growing crystal. This depends largely on the diffusion rate of the molecules of concern. So what are Textures of Igneous Rocks…. The term texture is defined as the mutual relationship of different mineralogical constituents in a rock. It is determined by the size, shape and arrangement of mineral grains in a rock. The grain size of an igneous rock depends on the rate of cooling of the magma. In general, slower is the rate of cooling, the coarser is the grain of the rock. In the study of the texture four points are considered. They are, Degree of crystallization Granularity or Size of grains Shape of crystals Mutual relationship between mineral grains Degree of crystallization In igneous rocks crystallanity ranges from entirely of Crystals to entirely of Glass. -

Introduction to Structural Geology

Introduction to Structural Geology Patrice F. Rey CHAPTER 1 Introduction The Place of Structural Geology in Sciences Science is the search for knowledge about the Universe, its origin, its evolution, and how it works. Geology, one of the core science disciplines with physics, chemistry, and biology, is the search for knowledge about the Earth, how it formed, evolved, and how it works. Geology is often presented in the broader context of Geosciences; a grouping of disciplines specifically looking for knowledge about the interaction between Earth processes, Environment and Societies. Structural Geology, Tectonics and Geodynamics form a coherent and interdependent ensemble of sub-disciplines, the aim of which is the search for knowledge about how minerals, rocks and rock formations, and Earth systems (i.e., crust, lithosphere, asthenosphere ...) deform and via which processes. 1 Structural Geology In Geosciences. Structural Geology aims to characterise deformation structures (geometry), to character- ize flow paths followed by particles during deformation (kinematics), and to infer the direction and magnitude of the forces involved in driving deformation (dynamics). A field-based discipline, structural geology operates at scales ranging from 100 microns to 100 meters (i.e. grain to outcrop). Tectonics aims at unraveling the geological context in which deformation occurs. It involves the integration of structural geology data in maps, cross-sections and 3D block diagrams, as well as data from other Geoscience disciplines including sedimen- tology, petrology, geochronology, geochemistry and geophysics. Tectonics operates at scales ranging from 100 m to 1000 km, and focusses on processes such as continental rifting and basins formation, subduction, collisional processes and mountain building processes etc. -

Geology.Gsapubs.Org on 23 September 2009

Downloaded from geology.gsapubs.org on 23 September 2009 Geology Porphyroblast rotation and strain localization: Debate settled! Scott E. Johnson Geology 2009;37;663-666 doi: 10.1130/G25729A.1 Email alerting services click www.gsapubs.org/cgi/alerts to receive free e-mail alerts when new articles cite this article Subscribe click www.gsapubs.org/subscriptions/ to subscribe to Geology Permission request click http://www.geosociety.org/pubs/copyrt.htm#gsa to contact GSA Copyright not claimed on content prepared wholly by U.S. government employees within scope of their employment. Individual scientists are hereby granted permission, without fees or further requests to GSA, to use a single figure, a single table, and/or a brief paragraph of text in subsequent works and to make unlimited copies of items in GSA's journals for noncommercial use in classrooms to further education and science. This file may not be posted to any Web site, but authors may post the abstracts only of their articles on their own or their organization's Web site providing the posting includes a reference to the article's full citation. GSA provides this and other forums for the presentation of diverse opinions and positions by scientists worldwide, regardless of their race, citizenship, gender, religion, or political viewpoint. Opinions presented in this publication do not reflect official positions of the Society. Notes © 2009 Geological Society of America Downloaded from geology.gsapubs.org on 23 September 2009 Porphyroblast rotation and strain localization: Debate settled! Scott E. Johnson Department of Earth Sciences, University of Maine, Orono, Maine 04469-5790, USA ABSTRACT (reviewed by Johnson, 1999; Carlson, 2002; This contribution shows unequivocally that porphyroblasts rotate relative to one another Johnson et al., 2006).