Selecting and Defining Indicators for Diabetes Surveillance in Germany CONCEPTS & METHODS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who Really Cares About Higher Education for Sustainable Development?

Journal of Social Sciences 7 (1): 24-32, 2011 ISSN 1549-3652 © 2010 Science Publications Who Really Cares About Higher Education For Sustainable Development? 1Torsten Richter and 2Kim Philip Schumacher 1Department of Biology, University of Hildesheim, Marienburger Platz 22, 31141 Hildesheim, Germany 2Institute for Spatial Analysis and Planning in Areas of Intensive Agriculture (ISPA), University of Vechta, Driverstrasse 22, 49377 Vechta, Germany Abstract: Problem statement: It is agreed that integrating Higher Education for Sustainable Development (HESD) into the curricula of universities is of key importance to disseminate the idea of sustainability. Especially the curricula of teacher-training should contain elements of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) due to the crucial role of future teachers in information propagation. Approach: In order to find out about the spreading of ESD into the curricula and whether or not it is of interest to university staff and students two interlinked studies were carried out in northern Germany during the summer term 2009 using standardized questionnaires. Results: A large gap between pilot projects and the statements of politicians on the one hand and the interest of academic staff and students in sustainability issues and the dissemination of HESD and ESD into the standard curricula of universities on the other was observed. Only 20% of respondents stated to have either given or attended courses relating to sustainability. Conclusion/Recommendations: Nevertheless there is a strong approval -

Indexing and Abstracting

INDEXING AND ABSTRACTING Open AIRE Zenodo EyeSource Polish Citation Database POL-index Library of Congress USA MPG S. F.X- Services World Wide Science Research Bib Datacite Wikidot ResearchID Thomson Reuters Berlin Scocial Science Center (WZB) TIB Leibniz Information Center for Science and Technology University Library Libraries of the Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (PTB) Kurt-Schwitters-Forum Library Online Catalogue Bavarian State Library (BSB) Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Library The Deutsches Museum Library HBZ Verbund Databank OPAC Database ULB Database THULB Database HTW Database Library German Central Interal Library (BVB) German Union Catalogue of Serials (ZDB) Southwest German Library Association (SWB) HEBIS Portal Library, Germany GVK Database Germany HUC Database Germany KOBV Portal Database Germany LIVIVO Search Portal Germany www.kwpublisher.com Regional Catalog Stock Germany UBBraunchweig Library Germany UB Greifswald Library Germany TIB Entire Stock Germany The German National Library of Medicine (ZB MED) Library of the Wissenschaftspark Albert Einstein Max Planck Digital Library Gateway Bayern GEOMAR Library of Ocean Research Information Access Global Forum on Agriculture Research Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Library Libraries of the Leipzig University Library of Bauhaus-Universität Weimar Germany Library of the Technical University of Central Hesse Library of University of Saarlandes, Germany Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Sachsen-Anhalt (ULB) Jade Hochschule Library -

Inspiring Practices – January 2016: Higher Education Helping Newly Arrived Refugees Meet Basic Needs and Ease Social Integration of Refugees

Inspiring practices – January 2016: Higher Education helping newly arrived refugees Meet basic needs and ease social integration of refugees This list is the result of responses to an EU Survey launched by the European Commission on 24 September 2015 among universities and student organisations. It has been further completed following a workshop organised on 6 October 2015 with 25 representatives of Erasmus+ National Agencies, universities and student organisations. The aim is not to be exhaustive, but to share some practices taking place in different parts of the EU. Challenges Inspiring practices (examples italicised) Accomodation of refugees in gyms/emergency sleeping place (Universität Leipzig; the University of Helsinki; Luleå University of Technology; Although the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki hasn't encountered student refugees, it has already taken steps to accommodate and support them; Humak University of Applied Sciences looks into the possibility to open a reception center for young asylum seekers within one of its campuses). Support for refugees' basic needs, including food, health services, cloths, beverages (the University of Coimbra; Pädagogische Hochschule Kärnten / University College of Teacher Education Carinthia; MF Norwegian School of Theology; Laurea University of Applied Sciences; Vienna's University of Applied Sciences; the University of Turku). Setting up of informal student/staff networks to support refugees (Malmö university web platform for Refugees; Develop initiatives to Social projects run by local -

Governance and Management of German Universities

Governance and Management of German Universities Dissertation Der Wirtschaftswissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Augsburg zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Wirtschaftswissenschaften (Dr. rer. pol.) Vorgelegt von Sarah A.E. Stockinger (M.Sc. Organization Studies) Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Erik E. Lehmann Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Susanne Warning Vorsitzender der mündlichen Prüfung: Prof. Dr. Robert Klein Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 10.12.2018 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisor Erik E. Lehmann for his ideas, guidance and freedom, each at the proper time. For giving me the opportunity to grow as a researcher and person. My thanks are also granted to my second supervisor Susanne Warning for her always friendly ear as well as for valuable contributions and discussions. Last but for sure not least, I barely can express how grateful I am to my wonderful family and friends for their unconditional and precious companionship throughout one of my biggest challenges. Thank you. I Contents I Contents .................................................................................................................................. 3 II List of tables .......................................................................................................................... 5 III List of figures ...................................................................................................................... 7 IV List of attachments ............................................................................................................. -

ARTICLE Students’ Perceptions of Citizenship and Civic Engagement at Higher Education Institutions in Germany

Education in the North Volume number (year), http://www.abdn.ac.uk/eitn 1 ARTICLE Students’ Perceptions of Citizenship and Civic Engagement at Higher Education Institutions in Germany Javid Jafarov, [email protected] University of Vechta, Germany DOI: https://doi.org/10.26203/0s32-2652 Copyright: © 2018 Jafarov To cite this article: Jafarov, J., (2018). Students’ Perceptions of Citizenship and Civic Engagement at Higher Education Institutions in Germany, Education in the North, 25(3), pp. 49-72. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non- commercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Education in the North, 25(3) (2018), http://www.abdn.ac.uk/eitn 49 Students’ Perceptions of Citizenship and Civic Engagement at Higher Education Institutions in Germany Javid Jafarov, [email protected] University of Vechta, Germany Abstract Literature on citizenship emphasizes the role of education in providing an opportunity for young people to participate effectively in democratic life and society. However, this role and responsibility have mostly been imposed on schools, not higher education institutions. Being able to participate effectively in democracy is a complex issue that requires opportunities to gain skills, knowledge and strategies for effective engagement. So civic engagement at school level is not enough to foster civic engagement, as learning how to participate in democratic life and society as an informed and active citizen is a life-long process. This study investigates students’ perceptions of citizenship and the current situations and approaches at German universities with respect to civic engagement. -

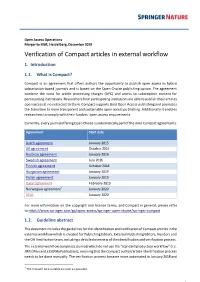

Verification of Compact Articles in External Workflow 1

Open Access Operations Margarita Bläß, Heidelberg, December 2019 Verification of Compact articles in external workflow 1. Introduction 1.1. What is Compact? Compact is an agreement that offers authors the opportunity to publish open access in hybrid subscription-based journals and is based on the Open Choice publishing option. The agreement combine the costs for article processing charges (APC) and access to subscription content for participating institutions. Researchers from participating institutions are able to publish their articles open access at no extra cost to them. Compact supports Gold Open Access publishing and promotes the transition to more transparent and sustainable open access publishing. Additionally it enables researchers to comply with their funders´ open access requirements. Currently, every journal offering Open Choice is automatically part of the nine Compact agreements: Agreement Start date Dutch agreement January 2015 UK agreement October 2015 Austrian agreement January 2016 Swedish agreement July 2016 Finnish agreement October 2018 Hungarian agreement January 2019 Polish agreement January 2019 Qatar agreement February 2019 Norwegian agreement1 January 2020 DEAL January 2020 For more information on the copyright and license terms, and Compact in general, please refer to https://www.springer.com/gp/open-access/springer-open-choice/springer-compact 1.2. Guideline abstract The document includes the guidelines for the identification and verification of Compact articles in the external workflow which is created for Publishing Editors, External Publishing Editors, Vendors and the OA Verification team, including a detailed overview of the identification and verification process. The external workflow comprises journals which do not use the “standard production workflow” (i.e. -

Long-Term Ecological Research

Long-Term Ecological Research Felix Müller · Cornelia Baessler · Hendrik Schubert · Stefan Klotz Editors Long-Term Ecological Research Between Theory and Application 123 Editors Felix Müller Cornelia Baessler University of Kiel Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Ecology Centre Research UFZ Olshausenstraße 75 Department of Community Ecology D-24118 Kiel Theodor-Lieser-Straße 4 Germany 06120 Halle [email protected] Germany [email protected] Hendrik Schubert University of Rostock, Stefan Klotz Institute of Biosciences Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Albert-Einstein-Straße 3 Research UFZ D-18055 Rostock Department of Community Ecology Germany Theodor-Lieser-Straße 4 [email protected] 06120 Halle Germany [email protected] ISBN 978-90-481-8781-2 e-ISBN 978-90-481-8782-9 DOI 10.1007/978-90-481-8782-9 Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg London New York Library of Congress Control Number: 2010925420 © Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2010 No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the Publisher, with the exception of any material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. Cover Images: Bavarian Forest National Park. Photos courtesy of Heinrich Rall. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer Science+Business Media (www.springer.com) Preface The components of global change operate on different spatial and temporal scales. Scientific analyses of this issue, however, often deal with shorter time scales, due to the typical funding duration of research projects. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Dr. Gerald Eisenkopf Professor for Business Administration University of Vechta, Postfach 15 53, 49364 Vechta, Germany Tel.: +49 4441 15127, E-Mail: [email protected] Education 2007 Dr.rer.pol. (PhD) in Economics, Universität Konstanz, Doctoral Program “Quantitative Economics and Finance”; Title of Thesis: “The Organization of Education”, Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Oliver Fabel. 2001 M.Litt. in Management, Economics, and International Relations; University of St Andrews 2001 Diplom in Psychology; Freie Universität Berlin, Exchange student at the Universitá di Padova (1998-99) Academic Employment Since 2016 Professor for Business Administration (Management of Social Services); Universität Vechta 2015-2016 Temporary Professor for Business Administration; Universität Konstanz, Department of Economics 2010-2015 Junior Professor for Personnel Economics; Universität Konstanz, Department of Economics (Positive evaluation in 2013) 2007-2010 Scientific Employee; Universität Konstanz, Department of Economics, Chair for Applied Economics (Prof. Dr. Fischbacher), and Thurgau Institute of Economics, Kreuzlingen, Switzerland 2006; 2009 Guest Researcher; University of Nottingham, School of Economics 2002-2007 Scientific Employee; Universität Konstanz, Department of Economics, Chair for Managerial Economics (Prof. Dr. Fabel) 1996-2000 Research Assistant; Max Planck Institute for Human Development, Berlin, Center for Educational Research, Prof. Dr. Baumert Publications “On the Role of Emotions in Experimental Litigation Contests” (2019, with Tim Friehe and Ansgar Wohlschlegel), International Review of Law & Economics, 57, 90-94 “The Long-Run Effects of Communication as a Conflict Resolution Mechanism” (2018), Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 154, 121-136. “Unequal Incentives and Perceived Fairness in Groups” (2018), Games, 9, 71, 1-18. “Punishment Motives for Small and Big Lies” (2017, with Ruslan Gurtoviy and Verena Utikal), Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 26, 2, 484–498. -

International Studies in Aquatic Tropical Ecology Student's Handbook

Fachbereich 02 Biologie / Chemie ISATEC International Studies in Aquatic Tropical Ecology Master of Science Course International Studies in Aquatic Tropical Ecology Student’s Handbook Programme Director & Chairman of the Examination Board Prof. Dr. Matthias Wolff Coordination Dr. Oliver Janssen-Weets INTRODUCTION TO THE ISATEC STUDY PROGRAMME .............................................. 4 PROFILE OF THE MSC-HOLDER ........................................................................................... 4 STUDY CONTENTS OF THE ISATEC PROGRAMME ........................................................ 5 (I) FUNDAMENTALS OF AQUATIC ECOLOGY .................................................................................. 5 (II) FUNDAMENTALS FOR THE EVALUATION & MANAGEMENT OF AQUATIC RESOURCES ............... 5 (III) GENERAL SKILLS ................................................................................................................... 6 PROGRAMME STRUCTURE .................................................................................................... 6 1ST TERM (AT UB) ......................................................................................................................... 8 2ND TERM (AT UB) ........................................................................................................................ 8 3RD TERM (AT TROPICAL PARTNER INSTITUTION) ........................................................................... 8 4TH TERM (AT UB) ........................................................................................................................ -

Here the Inter- Generational Contract Is Not Breached

Kathrin Komp-Leukkunen Faculty of Social Sciences, PO Box 9, 00014 University of Helsinki, Finland Phone: +358-(0)50-4487805, Email: [email protected] Short profile Researcher specialized in population ageing, life-courses, work and retirement, and welfare states. Strong background in country-comparative research and research methods. Well- developed analytical and organizational skills. Currently as- sociate professor in social policy, Helsinki University, Fin- land. Formerly Marie Curie fellow, treasurer of the European Sociological Association, and chair of the Research Network on Ageing in Europe. Expert assignments to the European Commission, the United Nations, the Council of Europe, the Bank of Finland, and the Governments of Finland and Roma- nia. 65+ publications, among them 19 articles in peer- reviewed journals and 3 books. Received media coverage. 650 000+ Euros in grants and scholarships. 30+ courses Scholar.google.com citations taught. Certified project manager. Basic pedagogical skills on February 03, 2021 certificate. Education Formal education 2021 Habilitation in sociology, Technical University of Dortmund, Germany Thesis: A life-course perspective on work and retirement 2014 Docentship in social gerontology, Helsinki University, Finland (equivalent to habilitation) 2006-10 PhD in sociology, VU University Amsterdam, Netherlands Thesis: The young old in Europe – Burden on or resource to the welfare state? 2003-06 Master in political science, Justus Liebig University Giessen, Germany Thesis: Das Wohlfahrtsregime -

Working Papers

Working Papers on Economic Geography Online Issue 2012-06 Volume 4 Annika Neubauer & Christine Tamásy Metropolitan Regions and Rural Development. The Case of Bremen-Oldenburg, Northwestern Germany web: www.ispa.uni-vechta.de/ Institute for Spatial Analysis and Planning in Areas of Intensive Agriculture Working Papers on Economic Geography | Issue 2012-06 | Volume 4 Metropolitan Regions and Rural Development. The Case of Bremen-Oldenburg, Northwestern Germany Authors: Annika Neubauer, Institute for Spatial Analysis and Planning in Areas of Intensive Agriculture, University of Vechta Email: [email protected] Christine, Tamásy, Institute for Spatial Analysis and Planning in Areas of Intensive Agriculture, University of Vechta Email: [email protected] Keywords: Metropolitan Regions, Rural Development, Governance, Bremen-Oldenburg in Northwestern Germany Abstract Metropolitan regions in Germany have gained an outstanding academic and political atten- tion with regard to spatial aspects in the past few years. In the course of globalization, the European expansion and the increasing significance of regions, metropolitan cities are seen as the most resilient, innovative and competitive spaces. Accordingly, the German spatial planning policy has included selected urban agglomerations into a strategy for competition and growth and developed the concept of metropolitan regions. This process has sparked a controversial discussion about a paradigm shift in German regional policy, as regional devel- opment has been oriented towards equal living conditions and interregional compensation ever since. Therefore, the fostering of metropolitan regions in Germany implies that the sup- port of structurally weak rural areas has become less important for regional development. This discourse with regard to metropolitan regions versus rural areas has resulted in political and regional negotiation processes, so that nearly half of the area of Germany has become integrated into metropolitan regions, including rural areas. -

Call to Restrict Neonicotinoids Dave Goulson and 232 Signatories

LETTERS Downloaded from Edited by Jennifer Sills Canada (8), governments elsewhere have Neonicotinoids threaten aquatic insects, such as this failed to take action. mayfly, as well as species that rely on them for food. Failure to respond urgently to this issue Call to restrict risks not only the continued decline in to inform decisions on how to manage neonicotinoids abundance and diversity of many ben- millions of acres of land nationwide. eficial insects, but also the loss of the The work of CRU scientists has helped http://science.sciencemag.org/ Neonicotinoids are the most widely used services they provide and a substantial guide hundreds of natural resource insecticides in the world (1). They are fraction of the biodiversity heritage of management decisions. Most recently, it applied to a broad range of food, energy, future generations. has informed energy exploration on the and ornamental crops, and used in Dave Goulson and 232 signatories* Colorado Plateau and offshore areas of domestic pest control (2). Because they are School of Life Sciences, University of Sussex, Falmer, Brighton, Alaska, a decision not to list the Sonoran neurotoxins, they are highly toxic to insects BN1 9QH, UK. Email: [email protected] desert tortoise as endangered, strategies *The full list of signatories is available online. (2), a group of organisms that contains the to manage the Klamath River Basin to majority of the described life on Earth, and REFERENCES sustain its Chinook salmon, and surveil- which includes numerous species of vital 1. P. Jeschke et al., J. Ag. Food Chem. 59, 2897 (2011). lance of deer to prevent the spread of importance to humans such as pollinators 2.