UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction Du Branch Patrimoine De I'edition

University of Alberta Ascending the Canadian Stage: Dance and Cultural Identity in the Indian Diaspora by Meera Varghese A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Music Edmonton, Alberta Spring 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-45746-7 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-45746-7 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Workshops & Research

WORKSHOPS & RESEARCH 20 JULY - 16 AUGUST 2014 Workshops in Contemporary Dance and Bodywork for all levels from beginners to professional dancers. Seven phases which can be attended independently from each other (each week- workshop: 1 class per day, each intensive-workshop: 2 classes per day) «impressions'14»: 20 July ! Week1: 21 - 25 July Intensive1: 26 + 27 July Week2: 28 July - 01 August! Intensive2: 02 + 03 August! Week3: 04 - 08 August! Intensive3: 09 + 10 August! Week4: 11 - 15 August ! «expressions'14»: 16 August Index 3 Artists listed by departments 4 - 133 All workshop descriptions listed by artists 134 - 149 All Field Project descriptions listed by artists 149 - 150 Pro Series description 2 CONTEMPORARY DANCE Jose Agudo | Conny Aitzetmueller | Kristina Alleyne | Sadé Alleyne | Laura Arís | Iñaki Azpillaga | Susanne Bentley | Marco Berrettini | Bruno Caverna | Marta Coronado | Zoi Dimitriou | Frey Faust | Ori Flomin | Saju Hari | Sascha Hauser aka CIONN | Kathleen Hermesdorf | Damien Jalet | Peter Jasko | German Jauregui | Kira Kirsch | Kerstin Kussmaul | Juliana Neves | Sabine Parzer | Rasmus Ölme | Francesco Scavetta | Rakesh Sukesh | Samantha Van Wissen | Hagit Yakira | David Zambrano IMPROVISATION Marco Berrettini | Adriana Borriello | Alice Chauchat | Ivo Dimchev | Zoi Dimitriou | Defne Erdur | Judith Grodowitz | Miguel Gutierrez | Francesca Harper | Andrew Harwood de Lotbinière | Keith Hennessy | Damien Jalet | Martin Kilvády | Barbara Kraus | Aiko Kazuko Kurosaki | Jennifer Lacey | Benoît Lachambre | Nita Little | Eroca -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

Dance (Code No

DANCE (CODE NO. 056 TO 061) 2020-21 The objective of the theory and practical course in Indian Classical Dance, Indian Traditional Dance, Drama or Theatre forms is to acquaint the students with the literary and historical background of the Indian performing arts in general, arid dance drama form offered in particular. It is presumed that the students offering these subjects will have had preliminary training in the particular form, either within the school system or in informal education. The Central Board of Secondary Education being an All India Organization has its schools all over the country. In order to meet the requirements of the schools, various forms or regional styles have been included in the syllabus. The schools may OFFER ANY ONE OF THE STYLES. Since the syllabi are closely linked with the culture, it is desirable that the teachers also make themselves familiar with the aspects of Indian Cultural History; classical and medieval period of its literature. Any one style from the following may be offered by the students: INDIAN CLASSICAL DANCE (a) Kathak (b) Bharatnatyam (c) Kuchipudi (d) Odissi (e) Manipuri (f) Kathakali (A) KATHAK DANCE (CODE NO. 056) CLASS–XII (2020-21) Total Marks: 100 Theory Marks: 30 Time-2 Hours 1. A brief history with other classical dance styles of India. 2. Acquaintance with the life sketch of few great exponents from past and few from present of the dance form. 3. Elementary introduction to the text Natyashastra, Abhinaya Darpan: (a) Identification of the author and (approximate date). (b) Myths regarding the origin of dance according to each text. -

Vijayashri Vittal

Vijayashri Vittal Born and raised in a family of musicians, Vijayashri Vittal started her musical training from her grandmother, Krishnaveni and her father, Vidwan Vittal Ramamurthy, an internationally acclaimed violinist and under the tutelage of Vidwan SP Ramh. Currently she is undergoing advanced training from world renowned vocalist, Vidushi Bombay Jayashri. Her journey in Bharatanatyam also began at the same time under the able tutelage of Vidwan Vijay Madhavan, disciple of Padmashri Chitra Visweswaran. Vijayashri was truly blessed to perform her Bharatanatyam arangetram in 2008 in the gracious presence of legendary Padmabhushan Lalgudi Jayaraman Sir. Her rigorous training under great gurus like Bombay Jayashri and Vijay Madhavan has opened avenues for her to groom herself not only as a performing artiste, but also as a teacher and creative collaborator, thus making her a multifaceted artist. Vijayashri regularly performs charity concerts in old age homes and for differently abled children through the Bhoomika Trust. As part of the Hitham Trust and Swami Dayananda Educational Trust (SDET), she teaches music to around 300 underprivileged children in Manjakudi and Tiruvarur, villages in South India. She strongly believes that music has the power to heal people. She has been working with children in the autistic spectrum using Carnatic music. Every year, she joins hands with her family and plays a vital role in conducting the ‘Karunbithil Shibira’ at their ancestral home in Nidle, Dharmasthala. Vijayashri has given many vocal and Bharatanatyam performances in the December Music Festival, Chennai and other reputed venues in India. She has had the privilege to travel around the world with her Guru and has also given solo performances at few major cities abroad. -

The Long Term You Cannot Afford

e LONG TERM you caot aÿord. on e distribuon of e TOXIC INVOCATIONS .– WITH Edna Bonhomme BPoC Environmenta and Cimate Justice Coective (Imeh Ituen and Rebecca Abena Kennedy-Asante) Center for Intersectiona Justice (Emiia Roig) Yoanda Ariadne Coins Discard Studies (Aex Zahara and Josh Lepawsky) Angea Fournoy The Forest Curricuum (Pujita Guha and Abhijan Toto) Hazardous Traves (Ayushi Dhawan, Maximiian Feichtner and Simone Müer) Hyoung-Min Kim and Gabrie Gaindez Cruz Jessika Khazrik Laboratory for Aesthetics and Ecoogy (Ida Bencke) Latedjou Liping Ting Mother the Verb (Ivan “Ivy” Monteiro) Franziska Pierwoss Raqs Media Coective (Shuddhabrata Sengupta) Matana Roberts Huda Rós Guðnadóttir Tomás Saraceno and the Aerocene Foundation Aexis Shotwe Stephan Thierbach Françoise Vergès Wearebornfree! Empowerment Radio (Moro Yapha) XR Extinction Rebeion (Kate Sagovsky) among others CURATORS Antonia Aampi Caroine Ektander CO¨CURATORS Jasmina A-Qaisi Kamia Metway ARTISTIS DIRECTOR Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung PROJECT TEAM Monioa Iupeju António Pedro Mendes Oa Zieińska CURATORIAL ASSISTANT Mahnoor Zehra Lodhi MANAGEMENT Lema Sikod Lynhan Baatbat-Hebock COMMUNICATION Anna Jäger GRAPHIC DESIGN Esa Westreicher Lii Somogyi SOUND ENGINEER Kay Bennet Kruthoff LIVE STREAM Boiing Head The project is funded by Hauptstadtkuturfonds and the Foundation for Arts Initiatives. With additiona support by the Mondriaan Fund, Goethe-Institut / Max Mueer Bhavan Kokata, Goethe Institut Pakistan, White Space Beijing, The Visua Arts Fund Iceand, DAAD Artists-in-Berin Program and the Berin Senate Department for Cuture and Europe. SAVVY Contemporary T Laboratory of Form-Ideas THE LONG TERM YOU CANNOT AFFORD. ON THE DISTRIBUTION OF THE TOXIC is the third chapter of SCHEDULE our ong-term investigation THE INVENTION OF SCIENCE. -

Tradition and the Individual Dancer

1: Tradition and the Individual Dancer History and Innovation in a Classical Form Critical accounts and promotional materials frequently refer to bharata natyam as “ancient.” The dance form’s status as traditional and classical seems to render it fixed, even timeless. A connection to the past appears to be a given for this dance practice. Even on closer examination, a relationship to the past seems integral to the dance form’s identity, its content, and its structure. Present-day bharata natyam choreography draws from the dance practices of earlier decades and centuries. Its movement vocabulary derives from sadir, the solo dance per- formed by temple and court dancers in precolonial and colonial South India. The margam—the concert order that determines when in a program each dance piece appears—was standardized in the nineteenth century by the renowned musician- composers of the Thanjavur Quartet. The roots of bharata natyam extend still further back. For example, the mudras, or hand gestures, used today accord in both shape and meaning with those described in the Natyasastra, a Sanskrit dra- maturgical text, dating from the beginning of the Christian era. Similarly, an arangetram, or initial performance, described in the fifth-century Tamil epic Silappadikaram correlates with that of devadasi practitioners of the nineteenth century, which then established the protocol for twentieth-century debuts. Bharata natyam’s repertoire consists largely of songs written between the sev- enteenth and twentieth centuries. The poems of love and religious devotion that form the basis of the bharata natyam canon emerged from the musical and lit- erary traditions of previous centuries. -

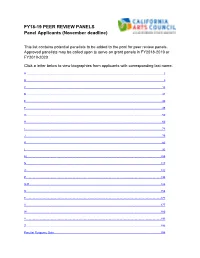

Panel Pool 2

FY18-19 PEER REVIEW PANELS Panel Applicants (November deadline) This list contains potential panelists to be added to the pool for peer review panels. Approved panelists may be called upon to serve on grant panels in FY2018-2019 or FY2019-2020. Click a letter below to view biographies from applicants with corresponding last name. A .............................................................................................................................................................................. 2 B ............................................................................................................................................................................... 9 C ............................................................................................................................................................................. 18 D ............................................................................................................................................................................. 31 E ............................................................................................................................................................................. 40 F ............................................................................................................................................................................. 45 G ............................................................................................................................................................................ -

Please Download, for More Information

Chitra Visweswaran Eminent dancer-teacher- choreographer, Chitra Visweswaran, a legend in the field of Indian dance, has the distinction of being a scholar, thinker & seeker. Deep- rooted training in dance under Smt T.A.Rajalakshmi & the doyen Vazhuvoor Sri B Ramiah Pillai an eclectic background & inner thirst for knowledge launched her on a voyage of discovery at a young age. Her research directed towards the extension of the existing Bharatanatyam repertoire has led to the creation of a voluminous body of work, covering the margam, thematic solo, group /dance theatre productions, which reflect individuality and are a synergy of tradition & innovation. Her work has been enriched by the music of her vocalist- musician - composer husband, Visweswaran, who incidentally, was the nephew of the Carnatic Legend G N Balasubramaniam. Chitra Visweswaran’s formal training in dance began with Western Classical Ballet in London at the age of five, but, in actuality, her first Guru, at the age of three, was actually her mother, Smt. Rukmini Padmanabhan, who was an excellent dancer, trained in the Uday Shankar School of dance and Bharatanatyam. It is to her that Chitra owes her artistic and creative vision. To this was harnessed an insatiable intellectual and cerebral quest which she owes to her father, Sri. N. Padmanabhan, a brilliant Engineer. After initiation into dance by her mother, Chitra undertook training in Western Classical Ballet in London, which was followed by training in Manipuri and Kathak in Calcutta. At the age of ten, she went under the tutelage of one of the best devadasis of Tiruvidaimardur, Smt.T.A.Rajalakshmi, who was settled in Calcutta. -

“Ksheerabdi Kannike”

Sudha Natarajan is a second year PhD student in Dancers’ Introdcution Pathology Department here at U of M. Sudha Neela Moorty began her training in Kuchipudi under Smt. Sasikala Penumarthi, a senior disciple of Padmabhushan Dr. Vempati Chinna Satyam, in 1991. During the summer of 1998 she participated in “Kuchipudi Prathidwani”, a tour of the US by Dr. Vempati Chinna Satyam and his troupe. She also underwent training at the Kuchipudi Art Academy, Chennai, India during the fall of 1999. Sudha is currently continuing her training under Smt. Sandhyasree Athmakuri, Rochester, MI. Sailaja Pullela Neela Moorty is a graduate student at the University of Michigan finishing her Masters in The Indian Classical Music and Dance Group Business Administration and Masters in Health Services Administration this April. Neela is a University of Michigan, Ann Arbor disciple of Smt. Viji Prakash, director of the Shakti School of Bharata Natyam in Los Angeles, California. Because Neela was raised in Utah, Neela’s mother would drive her 8 hours each-way Presents to continue training under Smt. Viji Prakash. Neela has been a member of the Shakti Dance Company since 1989 and toured in major productions across the US, Canada, and India. She has played key roles in the ballets Shyama, Meera, and the Ms. Sailaja Pullela is an exponent in the leading Natyaanjali Bhagvad Gita. Neela performed her Arangetram dance traditions of South India- Kuchipudi. Born in (solo debut) in 1999 in Palo Alto, California. Since a family of ardent lovers of classical arts, music then, she has continued to present Bharata and dance have always been part of Sailaja's life. -

Banis / बानी and Schools Are Aplenty

PAPER: 3 Detail Study Of Bharatanatyam, Devadasis-Natuvnar, Nritya And Nritta, Different Bani-s, Present Status, Institutions, Artists Module 18 Institutions Of Bharatanatyam Present day Bharatanatyam banis / बानी and schools are aplenty. There are many branches of main banis and some as far as in New Jersey in USA or Ukhrul in Manipur! Since Bharatanatyam has spread far and wide, each dancer is adding something to what was learnt and trying to extend its boundaries and body. Many dancers are also teachers today, so they are adding new poses or postures and calling it sub banis or schools. Schools today mean individual teaching establishments, not a generic bani or style. It means in one city itself, say small town like Mysore or Baroda, there could be ten schools of Bharatanatyam. Each teaching same dance, differently. In that, there is no standardization. In one area of a big metro like Chennai or Bangalore, Mylapore or Malleswaram, there are over a dozen teachers teaching from same bani differently. This is not to break away as much as what one learnt from a guru and how much. Schools of Bharatanatyam today within one city can be in hundreds, especially nerve centre of dance like Chennai. The Dhananjayans, Chandrasekhars, Ambika Buch, Savitri Jagannath Rao, M.V. 1 Narasimhachari and Vasanthalakshmi, Sheejith Krishna, P.T. Narendran, Shijith Nambiar and Parvathy Menon teach the Kalakshetra style. J. Suryanarayanamurthy, a disciple of the Dhananjayans, is a popular teacher. Sreelatha Vinod, Tulsi Badrinath, Radhika Surajit, Shobana Bhalchandra are ardent disciples of the Dhananjayans and faithfully follow their teachers’ teachings. -

SIFAS Festival of Indian Classical Music and Dance Began in 2003, Has Become a Significant and Much Anticipated Event in the Indian Cultural Calendar of Singapore

PAPER: 3 Detail Study Of Bharatanatyam, Devadasis-Natuvnar, Nritya And Nritta, Different Bani-s, Present Status, Institutions, Artists Module 35 Bharatanatyam In Singapore The Early Years 19th Century {Pre-War Year} Singapore has a relatively short history of Bharatanatyam. Between the years 1819 to 1945, Indian workers were brought by the British to Singapore from various Indian provinces like Madras, Bengal, Punjab, Orissa and Gujarat who carried with them their culture and folk songs. There are also early 20th century Tamil literary accounts of courtesans in Singapore. Both Tamil and Telugu-speaking Devadasi-kalavantulu / कलावंतुल ू communities had arrived the region. In the early 20th century, classical dance and music from South India were performed by visiting dance troupes. Temples were the centers of music and dance from the 1920s to 1940s, and provided the artistes a platform for performance, especially during festivities like Navaratri and Mandalabhishekam / मंडलाभिशेकम. After having self-government in 1959, Singapore formed the Ministry of Culture to encourage the preservation and development of Chinese, Malay, and Indian dances. Bharatanatyam is said to have transmitted as one of the first South Asian Arts from India to Singapore. 1959-1969 are considered to be the pre-professional dance years as the economy was the main concern during that time. Therefore, the dance faced the years of struggle for establishment. The development of Bharatanatyam form in Singapore is based on its 1 social, economic and political development. Although there has always been a conflict and struggle for the acceptance and rejection of influence of western dance style, serious efforts have been made from time to time to preserve the authenticity of the art forms.