Crossover Sexual Offenses. Abstract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The DSM Diagnostic Criteria for Paraphilia Not Otherwise Specified

Arch Sex Behav DOI 10.1007/s10508-009-9552-0 ORIGINAL PAPER The DSM Diagnostic Criteria for Paraphilia Not Otherwise Specified Martin P. Kafka Ó American Psychiatric Association 2009 Abstract The category of ‘‘Not Otherwise Specified’’ (NOS) Introduction for DSM-based psychiatric diagnosis has typically retained diag- noses whose rarity, empirical criterion validation or symptomatic Prior to an informed discussion of the residual category for expression has been insufficient to be codified. This article re- paraphilic disorders, Paraphilia Not Otherwise Specified (PA- views the literature on Telephone Scatologia, Necrophilia, Zoo- NOS), it is important to briefly review the diagnostic criteria philia, Urophilia, Coprophilia, and Partialism. Based on extant for a categorical diagnosis of paraphilic disorders as well as the data, no changes are suggested except for the status of Partialism. types of conditions reserved for the NOS designation. Partialism, sexual arousal characterized by ‘‘an exclusive focus The diagnostic criteria for paraphilic disorders have been mod- on part of the body,’’ had historically been subsumed as a type of ified during the publication of the Diagnostic and Statistical Man- Fetishism until the advent of DSM-III-R. The rationale for con- uals of the American Psychiatric Association. In the latest edition, sidering the removal of Partialism from Paraphilia NOS and its DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), a para- reintegration as a specifier for Fetishism is discussed here and in a philic disorder must meet two essential criteria. The essential companion review on the DSM diagnostic criteria for fetishism features of a Paraphilia are recurrent, intense sexually arousing (Kafka, 2009). -

Handler/Fetish CYOA V2.3

Handler/Fetish CYOA v2.3 You meet a stranger whose face you can't see. She explains to you that she is the "Handler", a being with the ability to manipulate people's minds, interpersonal relationships and society. She is usually fair and doesn't abuse her powers too much, but lately she's been really bored and wants to have some fun. So she offers you a deal: you pick one or more of the following "Fetishes" she has, and you can use the gained points to acquire boons from her in the same deal. You get to choose beforehand how long the deal should last. You get the boons while the deal is in effect, or if the deal lasts for at least 10 years, you get the boons permanently. You can also make multiple deals. You can delay when deals start (though of course you won’t get boons from it until it starts). You can only pick each Fetish once across all your deals, you can’t “reuse them”. You also have to make your deals now, before your first deal takes effect. tl;dr: You can make deals. Each deal has a start time, a length, one or more fetishes, suboptions for those fetishes, and zero or more boons. You can’t pick the same Fetish in two different deals. How do you use this opportunity? Category I Fetishes Each gives you 2 points. There are also suboptions you can pick, that give or subtract points if you pick them. For example “-1p” means that it subtracts a point. -

List of Paraphilias

List of paraphilias Paraphilias are sexual interests in objects, situations, or individuals that are atypical. The American Psychiatric Association, in its Paraphilia Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fifth Edition (DSM), draws a Specialty Psychiatry distinction between paraphilias (which it describes as atypical sexual interests) and paraphilic disorders (which additionally require the experience of distress or impairment in functioning).[1][2] Some paraphilias have more than one term to describe them, and some terms overlap with others. Paraphilias without DSM codes listed come under DSM 302.9, "Paraphilia NOS (Not Otherwise Specified)". In his 2008 book on sexual pathologies, Anil Aggrawal compiled a list of 547 terms describing paraphilic sexual interests. He cautioned, however, that "not all these paraphilias have necessarily been seen in clinical setups. This may not be because they do not exist, but because they are so innocuous they are never brought to the notice of clinicians or dismissed by them. Like allergies, sexual arousal may occur from anything under the sun, including the sun."[3] Most of the following names for paraphilias, constructed in the nineteenth and especially twentieth centuries from Greek and Latin roots (see List of medical roots, suffixes and prefixes), are used in medical contexts only. Contents A · B · C · D · E · F · G · H · I · J · K · L · M · N · O · P · Q · R · S · T · U · V · W · X · Y · Z Paraphilias A Paraphilia Focus of erotic interest Abasiophilia People with impaired mobility[4] Acrotomophilia -

2018 Juvenile Law Cover Pages.Pub

2018 JUVENILE LAW SEMINAR Juvenile Psychological and Risk Assessments: Common Themes in Juvenile Psychology THURSDAY MARCH 8, 2018 PRESENTED BY: TIME: 10:20 ‐ 11:30 a.m. Dr. Ed Connor Connor and Associates 34 Erlanger Road Erlanger, KY 41018 Phone: 859-341-5782 Oppositional Defiant Disorder Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Conduct Disorder Substance Abuse Disorders Disruptive Impulse Control Disorder Mood Disorders Research has found that screen exposure increases the probability of ADHD Several peer reviewed studies have linked internet usage to increased anxiety and depression Some of the most shocking research is that some kids can get psychotic like symptoms from gaming wherein the game blurs reality for the player Teenage shooters? Mylenation- Not yet complete in the frontal cortex, which compromises executive functioning thus inhibiting impulse control and rational thought Technology may stagnate frontal cortex development Delayed versus Instant Gratification Frustration Tolerance Several brain imaging studies have shown gray matter shrinkage or loss of tissue Gray Matter is defined by volume for Merriam-Webster as: neural tissue especially of the Internet/gam brain and spinal cord that contains nerve-cell bodies as ing addicts. well as nerve fibers and has a brownish-gray color During his ten years of clinical research Dr. Kardaras discovered while working with teenagers that they had found a new form of escape…a new drug so to speak…in immersive screens. For these kids the seductive and addictive pull of the screen has a stronger gravitational pull than real life experiences. (Excerpt from Dr. Kadaras book titled Glow Kids published August 2016) The fight or flight response in nature is brief because when the dog starts to chase you your heart races and your adrenaline surges…but as soon as the threat is gone your adrenaline levels decrease and your heart slows down. -

TOWN of PORTER ZONING ORDINANCE -JULY 2015- Revised April 2018

TOWN OF PORTER ZONING ORDINANCE -JULY 2015- Revised April 2018 ROCK COUNTY, WISCONSIN TABLE OF CONTENTS TOWN OF PORTER ZONING ORDINANCE _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ARTICLE 1. INTRODUCTION Sec. 1-1. Authority.................................................................................................................................................3 Sec. 1-2. Title and Effective Date.........................................................................................................................3 Sec. 1-3. Purpose and Intent ................................................................................................................................3 Sec. 1-4. Compliance With Other Ordinances, Statutes, Rules, Regulations, and Plans...............................3 Sec. 1-5. Interpretation, Abrogation and Greater Restrictions, Severability, and Repeal ............................4 Sec. 1-6. Revision and Amendment .....................................................................................................................4 Sec. 1-7. Definitions...............................................................................................................................................4 ARTICLE 2. GENERAL PROVISIONS Sec. 2-1. Applicability .........................................................................................................................................23 Sec. 2-2. Suitability..............................................................................................................................................23 -

Sexual Deviations. Considerations Regarding Pedophilia - Mith and Reality

International Journal of Advanced Studies in Sexology ISSN 2668-7194 (print), ISSN 2668-9987 (online) © Sexology Institute of Romania https://www.sexology.ro/jurnal Vol. 1(1), 2019, 10-14 DOI: 10.46388/ijass.2019.12.112 SEXUAL DEVIATIONS. CONSIDERATIONS REGARDING PEDOPHILIA - MITH AND REALITY AMALIA BONDREA1*, CRISTIAN DELCEA1, 2 1Iuliu Hațieganu University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Cluj-Napoca, Romania 2Sexology Institute of Romania, Cluj-Napoca, Romania Abstract Taking to consideration the antropology venues, the medical disclosures regarding paraphilia, centered on pedophilia, the present paper tries to make an introduction review on the topic under discussion. However, regardless the type of studies made over the time, whether they consisted in questionnaires and forums where people were invited to comment upon this sexual disorder or deviation, to more complex medical research involving MRI scans and DNA analysis, none of them proved their effectiveness, or found a real cause. Keywords: paraphilia, pedophilia, child abuse, menthal disorder, sexual deviation. INTRODUCTION cases of „psychopathic personality with pathologic sexuality”. Sexual deviation or paraphilia is primary One of the most studied paraphiliac disor- a general term used for a menthal-sexual ders is the pedophilia, as it has the most cri- disorder, accepted on a large scale as beeing minal implications, the most inocent victims used for a sexual practice not approved by and is one of the most stigmatized mental di- the social norms, an abnormality or a sexual sorders. perversion and characterized by getting sexual The word pedophilia comes from the arousal from an object, strange situation, Greek word παῖς, παιδός (paîs, paidós), mea- fantasy, etc. -

Men's Sexual Rights

Men’s sexual rights versus women’s sex-based rights WHRC Webinar, 18 April 2020 Sheila Jeffreys Intro: Hello Sisters! We are all here because we are concerned about the destructive impact of the transgender activist movement, which campaigns for ‘gender identity’ rights, is having on women’s sex-based rights. I am going to talk today about where this problem came from. I shall argue that the transgender rights movement is actually a men’s sexual rights movement. It is one aspect of the phenomenon that has been taking place since the so-called sexual revolution of the 1960s and 1970s, of establishing men’s sexual freedom, their freedom to exercise the male sex right. The so-called sexual revolution of the 1960s and 70s unleashed a men’s sexual liberation movement which required that women and girls service men’s sexual desires. From it grew the sex industry in the form of pornography and the toleration or legalisation of all forms of prostitution. What were once called the ‘sexual perversions’ were also released and seen as an important aspect of men’s liberation. Their practitioners were relabelled ‘erotic’ or sexual minorities and they set about campaigning for their rights. The practices that men’s rights campaigners sought to normalise included, alongside their use of women in pornography and prostitution, sadomasochism, pedophilia and transvestism, which is now more commonly called transgenderism. A men’s sexual freedom agenda is in opposition to the rights of women to be free from violence and coercion, the rights to privacy and dignity, and to the integrity of their bodies. -

Personality Disorders

Welcome Please write your questions and pass them to the end of your isle. THANK YOU! Copyright CEUConcepts, yourceus, LPCAGA, 1 EAPWorks, TMHPros, ACOPSY LPCA, CEUConcepts, yourceus.com, Inc. American College of Psychotherapy, and EAP Works present Psychopathology, Differential Diagnosis, and the DSM-5: A Comprehensive Overview Copyright CEUConcepts, yourceus, LPCAGA, EAPWorks, TMHPros, ACOPSY 2 This training meets the requirements established under SB 319 /ACT377 and Composite Board Rule 135-12-.01 CE Approved by: ASWB #1239 ASWB #1104 Online LPCA(6923-30-17M) NBCC (#6762) #6071 Online/YourCEUs.com Copyright CEUConcepts, yourceus, LPCAGA, EAPWorks, TMHPros, ACOPSY 3 Psychopathology and Differential Diagnosis Course, 8 Modules 1. Module I: Introduction to the DSM-5 (5 core & 2 ethics) 2. Module II: Medical Conditions, and Lifestyle Contributing Mental Health Concerns (5 core & 1 ethics) 3. Module III: Neurocognitive Disorders, Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders, and Bipolar and Related Disorders (5 core & 1 ethics hours) 4. Module IV: Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, Dissociative Disorders, and Trauma and Stressor Related Disorders (5 hours) Copyright CEUConcepts, yourceus, LPCAGA, 4 EAPWorks, TMHPros, ACOPSY Psychopathology and Differential Diagnosis Course, 8 Modules 5. Module V: Anxiety Disorders and Depressive Disorders (5 core & 1 ethics hours) 6. Module VI: Somatic Symptom and Related Disorders, Neurodevelopmental Disorders, Elimination Disorders, and Feeding and Eating Disorders (5 hours) 7. Module -

Sex in the Ancient World from a to Z the Ancient World from a to Z

SEX IN THE ANCIENT WORLD FROM A TO Z THE ANCIENT WORLD FROM A TO Z What were the ancient fashions in men’s shoes? How did you cook a tunny or spice a dormouse? What was the daily wage of a Syracusan builder? What did Romans use for contraception? This new Routledge series will provide the answers to such questions, which are often overlooked by standard reference works. Volumes will cover key topics in ancient culture and society—from food, sex and sport to money, dress and domestic life. Each author will be an acknowledged expert in their field, offering readers vivid, immediate and academically sound insights into the fascinating details of daily life in antiquity. The main focus will be on Greece and Rome, though some volumes will also encompass Egypt and the Near East. The series will be suitable both as background for those studying classical subjects and as enjoyable reading for anyone with an interest in the ancient world. Already published: Food in the Ancient World from A to Z Andrew Dalby Sport in the Ancient World from A to Z Mark Golden Sex in the Ancient World from A to Z John G.Younger Forthcoming titles: Birds in the Ancient World from A to Z Geoffrey Arnott Money in the Ancient World from A to Z Andrew Meadows Domestic Life in the Ancient World from A to Z Ruth Westgate and Kate Gilliver Dress in the Ancient World from A to Z Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones et al. SEX IN THE ANCIENT WORLD FROM A TO Z John G.Younger LONDON AND NEW YORK First published 2005 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxfordshire, OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Ave., New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2006. -

Paraphilia - Wikipedia, the Freevisited Encyclopedia on 3/23/2016 Page 1 of 13

Paraphilia - Wikipedia, the freevisited encyclopedia on 3/23/2016 Page 1 of 13 Paraphilia From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Paraphilia (also known as sexual perversion and Paraphilia sexual deviation) is the Classification and external resources experience of intense Specialty Psychiatry sexual arousal to atypical objects, situations, or ICD-10 F65 (http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2015/en#/F65) individuals.[1] No consensus has been found MeSH D010262 (https://www.nlm.nih.gov/cgi/mesh/2016/MB_cgi? for any precise border field=uid&term=D010262) between unusual sexual interests and paraphilic ones.[2][3] There is debate over which, if any, of the paraphilias should be listed in diagnostic manuals, such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) or the International Classification of Diseases (ICD). The number and taxonomy of paraphilias is under debate; one source lists as many as 549 types of paraphilias.[4] The DSM-5 has specific listings for eight paraphilic disorders.[5] Several sub- classifications of the paraphilias have been proposed, and some argue that a fully dimensional, spectrum or complaint-oriented approach would better reflect the evidence.[6][7] Contents ◾ 1 Terminology ◾ 1.1 Homosexuality and non-heterosexuality ◾ 2Causes ◾ 3 Diagnosis ◾ 3.1 Typical versus atypical interests ◾ 3.2 Intensity and specificity ◾ 3.3 DSM-I and DSM-II ◾ 3.4 DSM-III through DSM-IV ◾ 3.5 DSM-IV-TR ◾ 3.6 DSM-5 ◾ 4 Management ◾ 5 Epidemiology ◾ 6 Legal issues ◾ 7 See also ◾ 8 References https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paraphilia 3/23/2016 Paraphilia - Wikipedia, the freevisited encyclopedia on 3/23/2016 Page 2 of 13 ◾ 9 External links Terminology Many terms have been used to describe atypical sexual interests, and there remains debate regarding technical accuracy and perceptions of stigma. -

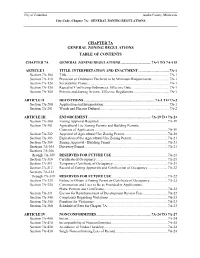

Chapter 7A General Zoning Regulations Table of Contents

City of Columbus Anoka County, Minnesota City Code, Chapter 7A: GENERAL ZONING REGULATIONS CHAPTER 7A GENERAL ZONING REGULATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 7A GENERAL ZONING REGULATIONS .................................. 7A-1 TO 7A-115 ARTICLE I TITLE, INTERPRETATION AND ENACTMENT. ................................. 7A-1 Section 7A-100 Title .................................................................................................................. 7A-1 Section 7A-110 Provision of Ordinance Declared to be Minimum Requirements ................... 7A-1 Section 7A-120 Severability Clause .......................................................................................... 7A-1 Section 7A-130 Repeal of Conflicting Ordinances, Effective Date .......................................... 7A-1 Section 7A-140 Permits and Zoning Actions, Effective Regulations........................................ 7A-1 ARTICLE II DEFINITIONS ............................................................................... 7A-1 TO 7A-2 Section 7A-200 Application and Interpretation ......................................................................... 7A-1 Section 7A-201 Words and Phrases Defined ............................................................................. 7A-2 ARTICLE III ENFORCEMENT ...................................................................... 7A-19 TO 7A-23 Section 7A-300 Zoning Approval Required ............................................................................ 7A-19 Section 7A-301 Agricultural Use Zoning Permits and -

11. the Scope of Prohibited Content

11. The Scope of Prohibited Content Contents Summary 259 Overview of the RC category 260 The current scope of RC content 262 Certain matters presented in an offensive way—Code item 1(a) 262 Offensive depictions or descriptions of children—Code item 1(b) 264 Promoting, inciting or instructing in crime—Code item 1(c) 265 Advocating a terrorist act—Act s 9A 267 Computer games that are unsuitable for minors 268 Renaming the RC category 268 Reforming the scope of Prohibited content 269 Community standards 270 Prohibited and ‘illegal’ content 272 Content depicting sexual fetishes 275 Content promoting, inciting or instructing in crime 276 Detailed instruction in drug use 278 A narrower Prohibited category 279 Pilot study into community attitudes to higher-level media content 279 Summary 11.1 This chapter discusses the scope of the current Refused Classification (RC) category and the legislative framework defining RC content. Under the current framework, RC content is essentially banned, and its sale and distribution is prohibited by Commonwealth, state and territory enforcement legislation. The ALRC recommends that, under the Classification of Media Content Act, the RC category should be named ‘Prohibited’ to better reflect the nature of the category. 11.2 The RC category has been criticised for being overly broad in various ways, including by covering content that depicts or describes particular sexual fetishes, which are legal between consenting adults, or instructs in matters of crime or violence. 11.3 The ALRC recommends that the Classification of Media Content Act should frame the ‘Prohibited’ category more narrowly than the current ‘Refused Classification’ category.