1 the More You Know: Incorporating Data and Research to Limit The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

We Applaud Gulfshore Playhouse for Another Year of Great Performances

Experience, Knowledge, Proven Results. FROM OLD NAPLES TO NAPLES SQUARE TO THE ISLES OF COLLIER PRESERVE Whether you are selling your home or condo or buying a home or condo, call me and let’s get started! BRUCE MILLER (239) 206-0868 720 5th Avenue South, Suite 201, Naples, FL 34102 [email protected] www.NaplesBeachesRealEstate.com CERTIFIED LUXURY HOME MARKETING SPECIALIST®, REALTOR® Welcome to Gulfshore Playhouse. On behalf of the law firm Denton’s Cohen & Grigsby, we are honored to serve once again as a corporate partner of Gulfshore Playhouse and to play a supporting role in bringing first class, professional theatre to Naples. For more than a decade, Denton’s Cohen & Grigsby has been practicing A Culture of Performance in Southwest Florida, representing clients with sound business counsel, innovative legal thinking, and a powerful understanding of the dynamics that shape our world. We are particularly proud of our collaboration with Gulfshore Playhouse which assists with bringing the arts and education to area schools, including the ThinkTheatre cross-curricular program, the STAR Academy afterschool and summer programs, the community partnerships, and more. Our partnership with Gulfshore Playhouse is a way of extending our firm’s high level of commitment to the arts, enriching the communities in which we serve. We hope you enjoy tonight’s performance and continue to support Gulfshore Playhouse, an exceptional cultural resource and treasure for our community. Sincerely, Jason Hunter Korn Managing Director, Denton’s Cohen & Grigsby, Florida A Letter from the Founder elcome home. I am sure I need not tell you how unspeakably thrilled I am that after EIGHT WMONTHS of darkness we are able to safely gather and present you with a season filled with a variety of unique opportunities created expressly with the safety of our actors, staff, and of course YOU in mind. -

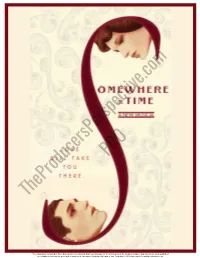

Theproducersperspective.Com

PRO TheProducersPerspective.com www.SomewhereInTime.com 1 The information contained in these documents is confidential, privileged and only for the information of the intended recipient and may not be used, published or redistributed without the prior written consent of Davenport Theatrical Enterprises, Inc. Copyright © 2016 Davenport Theatrical Enterprises, Inc. TABLE OF CONTENTS A Note From Ken Davenport ..........................................................................................3 Synopsis .................................................................................................................................4 Timeline .................................................................................................................................5 Fun Facts About Somewhere in Time .........................................................................6 World Premiere ................................................................................................................. 7 Creative Team ....................................................................................................................8 Production Team ........................................................................................................... 12 Press .................................................................................................................................. 13 The Materials ................................................................................................................. 14 Budget & -

Demographics Broadway Audience

THE DEMOGRAPHICS OF THE BROADWAY AUDIENCE 2018–2019 T HE DEMOGRAPHICS OF THE BROADWAY AUDIENCE 2018–2019 THE BROADWAY LEAGUE KAREN HAUSER NOVEMBER 2019 ©THE BROADWAY LEAGUE ISBN 978-0-9973744-8-3 CONTENTS 729 SEVENTH AVENUE T 212-764-1122 5TH FLOOR F 212-944-2136 NEW YORK, NY 10019 BROADWAYLEAGUE.COM Charlotte St. Martin President I Introduction and Summary Board of Governors November 2019 I Introduction and Summary Foreword 4 Foreword 4 Thomas Schumacher Executive Summary 5 Chairman Dear Colleague, Executive Summary 5 Gina Vernaci Vice Chair of the Road We are pleased to share with you The Demographics of the Elliot Greene II Demographics of the Broadway Audience Secretary/Treasurer Broadway Audience for the 2018–2019 season. Our audiences Place of Residence 8 Robert E. Wankel have continued to grow, and admissions have reached an all- II Demographics of the Broadway Audience Immediate Past Chairman time high of 14.8 million! Gender 16 Place of Residence 8 Richard Baker Age 18 Moreover, our shows are attracting people from all over the Gender 16 Meredith Blair Ethnic Background 22 Michael Brand world. This season, foreign visitors accounted for 2.8 million Maggie Brohn Age 18 admissions. This international component is especially excit- Education 25 Stephen Byrd Ethnic Background 22 Jeff Chelesvig ing, as visitors from farther away tend to stay longer and spend Annual Household Income 28 Robert Cole Education 25 Jeff Daniel more money in the city, supporting our mission to make Broad- Frequency of Attendance 30 Ken Davenport way the greatest tourist attraction in the area. -

2018 Tony Award® for Best Revival of a Musical

WINNER! 2018 TONY AWARD® FOR BEST REVIVAL OF A MUSICAL OCTOBER 2019 • VOL. 1 Carson Center Box Office (270) 450-4444 “What a delight it is to enter the world of ONCE ON THIS ISLAND!” raves The New York Times. Winner of the 2018 TONY AWARD FOR BEST REVIVAL OF A MUSICAL, ONCE ON THIS ISLAND is the sweeping, universal tale of Ti Moune, a fearless peasant girl in search of her place in the world, and ready to risk it all for love. Guided by the mighty island gods, Ti Moune sets out on a remarkable journey to reunite with the man who has captured her heart. The groundbreaking vision of two-time Tony Award nominated director Michael Arden (Spring Awakening revival) and acclaimed choreographer Camille A. Brown (NBC’s Jesus Christ Superstar Live) conjures up “a place where magic is possible and beauty is apparent for all to see!” (The Huffington Post). With a score that bursts with life from Lynn Ahrens and Stephen Flaherty, the Tony Award-winning songwriters of Anastasia and Ragtime, ONCE ON THIS ISLAND is a timeless testament to theater’s unlimited possibilities. WELCOME HOME PADUCAH NATIVES McKynleigh Alden Abraham and Jamey Jennings Thank you to the LOCAL LIGHTWALKERS for Once on This Island! These Paducah Tilghman and McCracken County High School Students and Alumni deserve a round of applause for their assistance during the two-week technical and rehearsal period that took place at The Carson Center in preparation for the show’s national tour. John Dabu Andriah Hawthorne Ameri Thompson LeVion Decker Jlea Humphries Vic Tyler Elijah Garrett Brandon McFarland Kendrick Williams Jalen Harris Mark Taylor II Mikaya Woods 8 www.thecarsoncenter.org Carson Center Box Office (270) 450-4444 The Kentucky Arts Council, the state arts agency, supports The Carson Center with state tax dollars and federal funding from the National Endowment for the Arts. -

GTB Investor Packet

“A LAUGH OUT LOUD MUSICALPRO FOR EVERYONE!” - BroadwayWorld TheProducersPerspective.com www.GettinTheBandonBroadway.com Broadway – 2014-2015 Season The information contained in these documents is confidential, privileged and only for the information of the intended recipient and may not be used, published or redistributed without the prior written consent of Davenport Theatrical Enterprises, Inc. Copyright © 2016 Davenport Theatrical Enterprises, Inc. TABLE OF CONTENTS A Note from Ken Davenport .............................................................................2 Synopsis ........................................................................................................3 The Original Production ..................................................................................4 The Creative Process ......................................................................................5 Creative Team ................................................................................................6 Press ...........................................................................................................10 Budget & Projections ...................................................................................16PRO The Materials ...............................................................................................31 The Opportunity ............................................................................................32 Contact ........................................................................................................33 -

Once on This Island Friday, March 20, 2020; 7:30 Pm Saturday, March 21, 2020; 2 & 7:30 Pm Sunday, March 22, 2020; 1 & 6:30 Pm

Once on This Island Friday, March 20, 2020; 7:30 pm Saturday, March 21, 2020; 2 & 7:30 pm Sunday, March 22, 2020; 1 & 6:30 pm KEN DAVENPORT HUNTER ARNOLD NETWORKS PRESENTATIONS and CARL DAIKELER ROY PUTRINO BROADWAY STRATEGIC RETURN FUND H. RICHARD HOPPER BRIAN CROMWELL SMITH ROB KOLSON KEVIN LYLE MICHELLE RILEY/DR. MOJGAN FAJRAM INVISIBLE WALL PRODUCTIONS/ISLAND PRODUCTIONS present Book & Lyrics by Music by LYNN AHRENS STEPHEN FLAHERTY Based on the novel “My Love, My Love” by Rosa Guy featuring JAHMAUL BAKARE KYLE RAMAR FREEMAN TAMYRA GRAY CASSONDRA JAMES PHILLIP BOYKIN DANIELLE LEE GREAVES TYLER HARDWICK with MCKYNLEIGH ALDEN ABRAHAM BRIANA BROOKS GEORGE L. BROWN MICHAEL IVAN CARRIER MIMI CROSSLAND MARIAMA DIOP JAY DONNELL ALEX JOSEPH GRAYSON PHYRE HAWKINS SAVY JACKSON TATIANA LOFTON ROBERT ZELAYA and introducing COURTNEE CARTER Scenic Design Costume Design Lighting Design Sound Design Tour Sound Design DANE LAFFREY CLINT RAMOS JULES FISHER + PETER HYLENSKI SHANNON SLATON PEGGY EISENHAUER Orchestrations Original Vocal Arrangements Hair/Wig and Make-up Design “Found” Instrument Design ANNMARIE MILAZZO & MICHAEL STEPHEN FLAHERTY COOKIE JORDAN JOHN BERTLES & STAROBIN BASH THE TRASH Casting Associate Director Associate Choreographer Music Director TELSEY + COMPANY JUSTIN SCRIBNER RICKEY TRIPP STEVEN CUEVAS CRAIG BURNS, CSA Music Coordinator Tour Booking, Press & Marketing General Management Production Manager JOHN MILLER BOND THEATRICAL GROUP GENTRY & ASSOCIATES NETWORKS PRESENTATIONS GREGORY VANDER PLOEG Associate Producers Company Manager Production Stage Manager Executive Producer KAYLA GREENSPAN JAMEY JENNINGS KELSEY TIPPINS TRINITY WHEELER VALERIE NOVAKOFF Music Supervisor CHRIS FENWICK Choreographer CAMILLE A. BROWN Director MICHAEL ARDEN www.harriscenter.net FEB–MAR 2020 PROGRAM GUIDE 53 Once on This Island continued CAST McKynleigh Jahmaul Phillip Briana Alden Bakare Boykin Brooks Abraham George L. -

Kinky Boots at the 5Th Avenue Theatre Encore Arts Seattle

APRIL 2016 2015/16 SEASON MATILDA AUG 18 - SEPT 6, 2015 WATERFALL OCT 1 - 25, 2015 RODGERS & HAMMERSTEIN’S THE SOUND OF MUSIC NOV 24, 2015 - JAN 3, 2016 HOW TO SUCCEED IN BUSINESS WITHOUT REALLY TRYING JAN 28 - FEB 21, 2016 ASSASSINS FEB 27 - MAY 8, 2016 CO-PRESENTED AT ACT - A CONTEMPORARY THEATRE A NIGHT WITH JANIS JOPLIN MAR 25 - APR 17, 2016 KINKY BOOTS APRIL 27 - MAY 8, 2016 LERNER & LOEWE’S PAINT YOUR WAGON JUNE 2 - 25, 2016 A GENTLEMAN’S GUIDE TO LOVE & MURDER JULY 12 - 31, 2016 April 2016 Volume 13, No. 8 Paul Heppner Publisher now through may 26th Susan Peterson Design & Production Director It’s time for a round of drinks! Ana Alvira, Robin Kessler, Shaun Swick, Stevie VanBronkhorst Join us Monday - Thursday from Production Artists and Graphic Design 2:30 - 5:30pm at SkyCity for drink Mike Hathaway Sales Director specials and delicious appetizers Brieanna Bright, Joey Chapman, Ann Manning served with breathtaking views. Seattle Area Account Executives Marilyn Kallins, Terri Reed San Francisco/Bay Area Account Executives Brett Hamil Online Editor Jonathan Shipley Associate Online Editor Ad Services Coordinator Carol Yip Sales Coordinator COME ON UP no reservations required 206.905.2100 | spaceneedle.com Leah Baltus Editor-in-Chief Paul Heppner Publisher Dan Paulus Art Director We don’t care Jonathan Zwickel Who You Sleep With. Senior Editor AS LONG AS Gemma Wilson Associate Editor YOU SLEEP WITH US Amanda Manitach Visual Arts Editor Learn how to shop Paul Heppner for a matt ress! President Every Saturday at 9:30am Mike Hathaway Vice President 300 NE 45th St. -

September 17 @ Southern

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE August 31, 2015 2013 Tony Award-Winning Best Musical Is Coming to Columbus’ Ohio Theatre October 6-11 Kinky Boots, the smash-hit musical that brings together four-time Tony® Award winner Harvey Fierstein (Book) and Grammy® Award-winning rock icon Cyndi Lauper (Tony Award winner for Best Score for Kinky Boots), opens at the Ohio Theatre October 6-11. Tickets for Kinky Boots at the Ohio Theatre (55 E. State St.) start at $33 and can be purchased at the CAPA Ticket Center (39 E. State St.), all Ticketmaster outlets, and online at www.ticketmaster.com. To purchase by phone, please call (800) 745-3000. Orders for groups of 20 or more may be placed by calling (614) 719-6900. The performance schedule is as follows: Tuesday, October 6, 7:30pm Wednesday, October 7, 7:30 pm Thursday, October 8, 7:30 pm Friday, October 9, 8 pm Saturday, October 10, 2 pm & 8 pm Sunday, October 11, 1 pm & 6:30 pm Directed and choreographed by Tony Award-winner Jerry Mitchell, Kinky Boots is represented around the world with the Broadway company now in its third year, a North American First National Tour that launched in September 2014, a Toronto production that opened in June 2015, a London production opening in September 2015, and a Melbourne production opening in October 2016. A Korean production of Kinky Boots ran from December 2014-February 2015. The Grammy Award-winning Original Broadway Cast Recording of Kinky Boots is available on Sony Masterworks Broadway. Kinky Boots took home six 2013 Tony Awards, the most of any show in the season, including Best Musical, Best Score (Cyndi Lauper), Best Choreography (Jerry Mitchell), Best Orchestrations (Stephen Oremus), and Best Sound Design (John Shivers). -

The Dinner Theatre of Columbia P R E S E N T S

The Dinner Theatre of Columbia P r e s e n t s January 10 - March 22, 2020 Next at TOBY’S THEATRICALS March 27 - June 7, 2020 THE DINNER THEATRE OF COLUMBIA Production of Kinky Boots Book by Harvey Fierstein Music and Lyrics by Cyndi Lauper Based on the Miramax motion picture Kinky Boots Written by Geoff Deane and Tim Firth Artistic Director Toby Orenstein Director Mark Minnick Choreographers Mark Minnick & David Singleton Musical Director/Orchestrations Ross Scott Rawlings Costume Designer Scenic/Lighting Designer Sound Designer Janine Sunday David A. Hopkins Mark Smedley Cyndi Lauper wishes to thank her collaborators: Sammy James Jr., Steve Gaboury, Rich Morel and Tom Hammer, Stephen Oremus Originally Broadway Production Produced by DARYL ROTH HAL LUFTIG JAMES L. NEDERLANDER TERRY ALLEN KRAMER INDEPENDENT PRESENTERS NETWORKS CJ E&M JAYNE BARON SHERMAN JUST FOR LAUGHS THEATRICALS/JUDITH ANN ABRAMS YASHUHIRO KAWANA JANE BERGERE ALLAN S. GORDON & ADAM S. GORDON KEN DAVENPORT HUNTER ARNOLD LUCY & PHIL SUAREZ BRYAN BANTRY RON FIERSTEIN & DORSEY REGAL JIM KIERSTEAD/GREGORY RAE BB GROUP/CHRISTINA PAPAGJIKA MICHAEL DeSANTIS/ PATRICK BAUGH BRIAN SMITH/TOM & CONNIE WALSH WARREN TREPP and JUJAMCYN THEATERS Kinky Boots Is presented through special arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI. www.mtishows.com The videotaping or other video or audio recording of this production is strictly prohibited. Fog, haze, and strobe effects are used in this performance. Toby’s Dinner Theatre of Columbia • 5900 Symphony Woods Road • Columbia, MD 21044 Box Office 410-730-8311 • 800-88TOBYS (800-888-6297) www.tobysdinnertheatre.com MUSIC | THEATRE | DANCE FILM | POETRY | VISUAL ARTS PERFORMANCES | GALLERIES CLASSES | LESSONS Join us for the 2019-2020 season, and experience the power of the arts! howardcc.edu/horowitzcenter BOX OFFICE 443-518-1500 • OPEN TUESDAY-FRIDAY 12-5 PM Good rates backed by Good Neighbor service That’s State Farm Insurance. -

Dateline • Venue Hollywood Pantages Theatre

® HOLLYWOOD PANTAGES THEATRE LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA DATELINE • VENUE HOLLYWOOD PANTAGES THEATRE TROIKA ENTERTAINMENT, LLC presents Book by Music & Lyrics by HARVEY FIERSTEIN CYNDI LAUPER Based on the Miramax motion picture Kinky Boots Written by Geoff Deane and Tim Firth starring CONNOR ALLSTON KENNETH MOSLEY KARIS GALLANT JAMES FAIRCHILD ASHLEY NORTH JAMES MAY JORDAN ARCHIBALD DEREK BRAZEAU GEOFF DAVIN LYNDA DEFURIA STEPHEN FOSTER HARRIS RYAN MICHAEL JAMES CHRIS KANE KIRBY LUNN ANDREW MALONE JULIAN MALONE REBECCA MASON-WYGAL MITCHELL MATYAS SHAUN NERNEY ANDREW NORLEN JACOB PAULSON ANDREW POSTON KELSEE SWEIGARD JENNY LIZ TAYLOR KIM TRUNCALE ERNEST TERRELLE WILLIAMS Scenic Design Costume Design Lighting Design Sound Design DAVID ROCKWELL GREGG BARNES KENNETH POSNER JOHN SHIVERS Associate Scenic Designer Associate Costume Designer Associate Lighting Designer Associate Sound Designer KEVIN DEPINET JIM HALL MITCHELL FENTON KEVIN KENNEDY Hair Design Make-up Design Associate Choreographer Associate Director JOSH MARQUETTE BRIAN STRUMWASSER RUSTY MOWERY DB BONDS Associate Hair Designer Music Supervisor Music Coordinator Casting Production Manager SABANA MAJEED ROBERTO SINHA TALITHA FEHR WOJCIK|SEAY HEATHER CHOCKLEY CASTING Exclusive Tour Direction Tour Marketing & Press General Manager THE ROAD COMPANY ALLIED TOURING BRIAN SCHRADER Music Supervision, Arrangements & Orchestrations by STEPHEN OREMUS Directed and Choreographed by JERRY MITCHELL Direction Recreated by Choreography Recreated by DB BONDS RUSTY MOWERY Original Broadway Production -

GTB Investor Packet Final

A NOTE ABOUT THE GTB INFORMATION PACKET The following pages consist of the investor information packet I use for Gettin’ The Band Back Together. They will give you an idea of how much information I give to potential investors to acquaint them with the offering. A reminder that if you are preparing anything other than your investment paperwork to give to your investors, you must speak to your attorney first. Raising money for commercial or non-profit ventures may be regulated by both Federal and State Securities Laws. As I’m sure you can understand, we cannot assume any liability in conjunction with your money raising activities. The materials in this document are protected under copyright and all rights are reserved. Copyright © 2014 Ken Davenport. All rights reserved worldwide. PRO TheProducersPerspective.com Copyright 2014 Ken Davenport 1 www.TheProducersPerspective.com The information contained in these documents is confidential, privileged and only for the information of the intended recipient and may not be used, published or redistributed without the prior written consent of Davenport Theatrical Enterprises, Inc. Copyright © 2016 Davenport Theatrical Enterprises, Inc. “A LAUGH OUT LOUD MUSICALPRO FOR EVERYONE!” - BroadwayWorld TheProducersPerspective.com www.GettinTheBandonBroadway.com Broadway – 2014-2015 Season The information contained in these documents is confidential, privileged and only for the information of the intended recipient and may not be used, published or redistributed without the prior written consent of Davenport -

Copyright 2014 Ken Davenport 1

Copyright 2014 Ken Davenport 1 www.TheProducersPerspective.com Thank you for reading my 50 Tips on How to Get Your Show off the Ground! These tips (or “Kenisms” as my office calls them) are actual quotes from me to people like you . producers, writers, artists and entrepreneurs of all types who are looking to get their shows off the ground. The Tips were given to these folks over the past several years during my Get Your Show Off The Ground seminar. The Get Your Show Off The Ground seminar is the first seminar I ever taught. I modeled it after a seminar I took with blogger Seth Godin. I plunked down $2,500 to be one of about 40 people in a room with Seth. We went around the room and presented Seth with a business problem . and he tackled it for us right there on the spot. Not only did I learn a ton from this marketing guru about my specific issue, but I found I learned even more from what he said to everyone else! And I made some fantastic networking connections (including someone who became a big investor of mine). So, when I started trying to come up with ways that I could help people produce more theater, I said, “I’m going to make my seminar just like Seth’s! But I’m going to make mine smaller (I only take 8 people) and a heck of a lot cheaper.” That was about five years ago, and well over a hundred people have taken the seminar and we’ve had some massive success stories.