A View from the Clan Stronghold of Dùn Èistean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inner and Outer Hebrides Hiking Adventure

Dun Ara, Isle of Mull Inner and Outer Hebrides hiking adventure Visiting some great ancient and medieval sites This trip takes us along Scotland’s west coast from the Isle of 9 Mull in the south, along the western edge of highland Scotland Lewis to the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides (Western Isles), 8 STORNOWAY sometimes along the mainland coast, but more often across beautiful and fascinating islands. This is the perfect opportunity Harris to explore all that the western Highlands and Islands of Scotland have to offer: prehistoric stone circles, burial cairns, and settlements, Gaelic culture; and remarkable wildlife—all 7 amidst dramatic land- and seascapes. Most of the tour will be off the well-beaten tourist trail through 6 some of Scotland’s most magnificent scenery. We will hike on seven islands. Sculpted by the sea, these islands have long and Skye varied coastlines, with high cliffs, sea lochs or fjords, sandy and rocky bays, caves and arches - always something new to draw 5 INVERNESSyou on around the next corner. Highlights • Tobermory, Mull; • Boat trip to and walks on the Isles of Staffa, with its basalt columns, MALLAIG and Iona with a visit to Iona Abbey; 4 • The sandy beaches on the Isle of Harris; • Boat trip and hike to Loch Coruisk on Skye; • Walk to the tidal island of Oronsay; 2 • Visit to the Standing Stones of Calanish on Lewis. 10 Staffa • Butt of Lewis hike. 3 Mull 2 1 Iona OBAN Kintyre Islay GLASGOW EDINBURGH 1. Glasgow - Isle of Mull 6. Talisker distillery, Oronsay, Iona Abbey 2. -

Lionel Mission Hall, Lionel, Isle of Lewis, HS2 0XD Property

Lionel Mission Hall, Lionel, Isle of Lewis, HS2 0XD Property Detached church building located in the peaceful village of Lionel, to the north of the Isle of Lewis. With open views surrounding, the property benefits from a wonderful spot and presents a very attractive purchase opportunity and is only a short drive from the main town of Stornoway. Entrance Vestibule: 2.59m x 2.25m Main Hall: 10.85m x 6.46m Gross Internal Floor Area: 76.2 m2 Services The property is serviced by electricity only. Mains water and sewer are conveniently located nearby. Grounds The property is situated on a small plot, with grounds surrounding the church bounded by wire fencing. Planning The Church Hall is not listed, and could be used, without the necessity of obtaining change of use consent, as a Creche, day nursery, day centre, educational establishment, museum or public library. It also has potential for a variety of other uses, such as retail, commercial or community uses, subject to obtaining the appropriate consents. Conversion to residential accommodation is also possible, again subject to the usual consents. Local Area Lionel is a village on the North of the Isle of Lewis and is less than a ten-minute drive from the Butt of Lewis. The village benefits from excellent access routes around the island and is only 26 miles from Stornoway. The neighbouring villages provide a wide range of amenities including shop, filling station, school, post office, bar restaurant, laundrette and charity shop. Stornoway is the main town of the Western Isles and the capital of Lewis. -

Annual Report 2004

Fèisean nan Gàidheal The National Association of Gaelic Arts Youth Tuition Festivals Aithisg Bhliadhnail 2004 Annual Report 2004 Fèisean nan Gàidheal Taigh a’ Mhill Port-Rìgh "When heads of state visit this country I’m proud to show them An t-Eilean Sgitheanach our architectural heritage whether it’s a castle, a cottage, or a IV51 9BZ House for an Art Lover. I’m delighted they can hear young musicians from this Academy (RSAMD), and from the Fèis Fòn 01478 613355 movement, play the music of our country." Facs 01478 613399 Post-d [email protected] Jack McConnell MSP, First Minister, St Andrew’s Day Speech, November 2003 www.feisean.org Fèisean nan Gàidheal Aithisg Bhliadhnail 2004 Annual Report 2004 Facal bhon Chathraiche Introduction from the Chairperson 1 FÈISEAN ANN AN ALBA & FÈIS FACTS 2003-04 2 STAFFING 3 FINANCE 4 THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS 5 CORE ACTIVITIES & MEMBERSHIP SERVICES 6 DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS 2003-04 7 ADVOCACY and COLLABORATION WITH OTHER AGENCIES 8 FÈIS NEWS 9 FINANCIAL STATEMENT Appendix 1 Board Members 2003-04 Appendix 2 Fèis Contacts Fèisean nan Gàidheal is a company limited by guarantee, registration number SC 130071, and gratefully acknowledges the support of its core-funders Scottish Arts Council, The Highland Council and Highlands & Islands Enterprise 2 FACAL BHON CHATHRAICHE Thòisich mi mar Chathraiche Fèisean nan Gàidheal anns an Dùbhlachd an uiridh, a’ leantainn Iain MacDhòmhnaill, a thug seachad mòran bhliadhnaichean gu math soirbheachail anns an dreuchd. Tha e na thoileachadh dhomh Aithisg Bhliadhnail Fèisean nan Gàidheal 2004 a chur fo ur comhair, ann am bliadhna far an robh iomairt nam Fèisean a’ sìor-fhàs agus a’ leudachadh mar nach robh riamh roimhe. -

For Many in the Western Isles the Hebridean

/ - Carpet World 0' /1 -02 3-*0 0-40' ,- 05 3 #$%&' Warehouse ( ) *!" 48 Inaclete Road, Stornoway Tel 01851 705765 www.carpetworldwarehouse.co.uk !" R & G Ury) '$ &$( (Ah) '$ &#&#" ! Jewellery \ "#!$% &'()#'* SS !" !#$$ The local one %% % &##& %# stop solution for all !7ryyShq&"%#% your printing and design needs. GGuideuide ttoo RRallyally HHebridesebrides 22017:017: 01851 700924 [email protected] www.sign-print.co.uk @signprintsty SSectionection FFourour Rigs Road, Stornoway HS1 2RF ' * * + , - + .-- $ ! !"# %& " # $ %&'& $ ())' BANGLA SPICE I6UVS6G SPPADIBTG6U@T :CVRQJ1:J Ury) '$ &$ $$ G 8hyy !" GhCyvr #$!% '$ & '%$ STORNOWAY &! &' ()*+! Balti House ,*-.*/,0121 3 4& 5 5 22 Francis Street Stornoway •# Insurance Services RMk Isle of Lewis HS1 2NB •# Risk Management t: 01851 704949 # ADVICE • Health & Safety YOU CAN www.rmkgroup.co.uk TRUST EVENTS SECTION ONE - Page 2 www.hebevents.com 03/08/17 - 06/09/17 %)% % * + , , -, % ( £16,000 %)%%*+ ,,-, %( %)%%*+ ,,-, %( %*%+*.*,* ' %*%+*.*,* ' presented *(**/ %,, *(**/ %,, *** (,,%( * *** (,,%( * +-+,,%,+ *++,.' +-+,,%,+ *++,.' by Rally #/, 0. 1.2 # The success of last year’s Rally +,#('3 Hebrides was marked by the 435.' !"# handover of a major payment to $%!&' ( Macmillan Cancer Support – Isle of Lewis Committee in mid July. The total raised -

Siadar Wave Energy Project Siadar 2 Scoping Report Voith Hydro Wavegen

Siadar Wave Energy Project Siadar 2 Scoping Report Voith Hydro Wavegen Assignment Number: A30708-S00 Document Number: A-30708-S00-REPT-002 Xodus Group Ltd 8 Garson Place Stromness Orkney KW16 3EE UK T +44 (0)1856 851451 E [email protected] www.xodusgroup.com Environment Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION 6 1.1 The Proposed Development 6 1.2 The Developer 8 1.3 Oscillating Water Column Wave Energy Technology 8 1.4 Objectives of the Scoping Report 8 2 POLICY AND LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK 10 2.1 Introduction 10 2.2 Energy Policy 10 2.2.1 International Energy Context 10 2.2.2 National Policy 10 2.3 Marine Planning Framework 11 2.3.1 Marine (Scotland) Act 2010 and the Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009 11 2.3.2 Marine Policy Statement - UK 11 2.3.3 National and Regional Marine Plans 11 2.3.4 Marine Protected Areas 12 2.4 Terrestrial Planning Framework 12 2.5 Environmental Impact Assessment Legislation 12 2.5.1 Electricity Works (Environmental Impact Assessment) (Scotland) Regulations 2000 13 2.5.2 The Marine Works (Environmental Impact Assessment) Regulations 2007 13 2.5.3 The Environmental Impact Assessment (Scotland) Regulations 1999 13 2.5.4 Habitats Directive and Birds Directive 13 2.5.5 Habitats Regulations Appraisal and Appropriate Assessment 13 2.6 Consent Applications 14 3 PROJECT DESCRIPTION 15 3.1 Introduction 15 3.2 Rochdale Envelope 15 3.3 Project Aspects 15 3.3.1 Introduction 15 3.3.2 Shore Connection (Causeway and Jetty) 15 3.3.3 Breakwater Technology and Structure 16 3.3.4 Parallel Access Jetty 17 3.3.5 Site Access Road 17 3.3.6 -

24 Upper Carloway, Isle of Lewis, HS2

24 Upper Carloway, Isle of Lewis, HS2 9AG In a superb elevated position overlooking beautiful views of Carloway Loch and across the surround- ing hillside, we offer for sale this cosy two bedroom property. The traditional style dwelling house boasts spacious and versatile family living accommodation with well proportioned rooms and a light and airy feel throughout. The property has been neutrally decorated and further enhanced by oil fired central heating and double glazing. Set within well presented, easily maintained garden grounds, with off road parking to the side. Located approximately 23 miles from Stornoway town the property is within a quiet traditional crofting township in the district of Carloway. There is a GP surgery in the village approximately 1/2 mile from the property and the primary schools are located in the neigh- bouring villages of Shawbost and Breasclete. Accommodation Kitchen Dining room Lounge Shower room 2 bedrooms Box room EPC Band F Ken Macdonald & Co. Lawyers & Estate Agents & Estate Lawyers Co. & Ken Macdonald Offers Over £90,000 9 Kenneth Street, Stornoway, Isle of Lewis HS1 2DP Tel: 01851 704040 Fax: 01851 705083 Email: [email protected] Website: www.kenmacdonaldproperties.co.uk Directions Travelling out of Stornoway town centre passing the Co-op superstore follow the main road travelling north across the Barvas moor. Take the first turning to your left after the filling station and follow the road for approximately 11 miles passing through the villages of Arnol, Bragar and Shawbost until you reach Carloway. Continue through Carloway turning to your right at the bridge, following the road signposted to Garenin. -

Anne R Johnston Phd Thesis

;<>?3 ?3@@8393;@ 6; @53 6;;3> 530>623? 1/# *%%"&(%%- B6@5 ?=316/8 >343>3;13 @< @53 6?8/;2? <4 9A88! 1<88 /;2 @6>33 /OOG ># 7PJOSTPO / @JGSKS ?UDNKTTGF HPR TJG 2GIRGG PH =J2 CT TJG AOKVGRSKTY PH ?T# /OFRGWS &++& 4UMM NGTCFCTC HPR TJKS KTGN KS CVCKMCDMG KO >GSGCREJ.?T/OFRGWS,4UMM@GXT CT, JTTQ,$$RGSGCREJ"RGQPSKTPRY#ST"COFRGWS#CE#UL$ =MGCSG USG TJKS KFGOTKHKGR TP EKTG PR MKOL TP TJKS KTGN, JTTQ,$$JFM#JCOFMG#OGT$&%%'($'+)% @JKS KTGN KS QRPTGETGF DY PRKIKOCM EPQYRKIJT Norse settlement in the Inner Hebrides ca 800-1300 with special reference to the islands of Mull, Coll and Tiree A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Anne R Johnston Department of Mediaeval History University of St Andrews November 1990 IVDR E A" ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS None of this work would have been possible without the award of a studentship from the University of &Andrews. I am also grateful to the British Council for granting me a scholarship which enabled me to study at the Institute of History, University of Oslo and to the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs for financing an additional 3 months fieldwork in the Sunnmore Islands. My sincere thanks also go to Prof Ragni Piene who employed me on a part time basis thereby allowing me to spend an additional year in Oslo when I was without funding. In Norway I would like to thank Dr P S Anderson who acted as my supervisor. Thanks are likewise due to Dr H Kongsrud of the Norwegian State Archives and to Dr T Scmidt of the Place Name Institute, both of whom were generous with their time. -

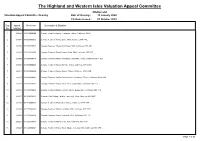

Appeal Citation List External

The Highland and Western Isles Valuation Appeal Committee Citation List Valuation Appeal Committee Hearing Date of Hearing : 15 January 2020 Citations Issued : 01 October 2019 Seq Appeal Reference Description & Situation No Number 1 268564 01/01/900009/0 Sewage Treatment Works, Headworks, Thurso, Caithness, KW14 2 268568 01/05/900001/2 Sewage Treatment Works, Glebe, Wick, Caithness, KW1 4NL 3 268207 01/05/900002/9 Sewage Treatment Works, North Head, Wick, Caithness, KW1 4JH 4 268208 01/05/900003/6 Sewage Treatment Works, Newton Road, Wick, Caithness, KW1 5LT 5 268209 01/09/900001/0 Sewage Treatment Works, Greenland, Castletown, Thurso, Caithness, KW14 8SX 6 268210 01/09/900002/7 Sewage Treatment Works, Barrock, Thurso, Caithness, KW14 8SY 7 268211 01/09/900003/4 Sewage Treatment Works, Dunnet, Thurso, Caithness, KW14 8XD 8 268217 01/09/900004/1 Sewage Treatment Works, Pentland View, Scarfskerry, Thurso, Caithness, KW14 8XN 9 268218 01/10/900004/1 Sewage Treatment Works, Thura Place, Bower, Wick, Caithness, KW1 4TS 10 268219 01/10/900005/8 Sewage Treatment Works, Auchorn Square, Bower, Wick, Caithness, KW1 4TN 11 264217 01/11/033541/3 Caravan, Caith Cottage, Hillside, Auckengill, Wick, Caithness, KW1 4XP 12 268935 01/11/900001/7 Sewage Treatment Works, Mey, Thurso, Caithness, KW14 8XH 13 268220 01/11/900002/4 Sewage Treatment Works, Canisbay, Wick, Caithness, KW1 4YH 14 268569 01/11/900005/5 Sewage Treatment Works, Auckengill, Wick, Caithness, KW1 4XP 15 268227 01/12/900001/4 Sewage Treatment Works, Reiss, Wick, Caithness, KW1 4RP 16 268228 -

Ken Macdonald & Co Solicitors & Estate Agents Stornoway, Isle Of

Ken MacDonald & Co 2 Lemreway, Lochs, Solicitors & Estate Agents Isle of Lewis,HS2 9RD Stornoway, Isle of Lewis Offers over £115,000 Lounge Description Offered for sale is the tenancy and permanent improvements of the croft extending to approximately 3.04 Ha. The permanent improvements include a well appointed four bedroomed detached dwellinghouse. Presented to the market in good decorative order however would benefit from updating of fixtures and fittings. Benefiting from oil fired central heating and timber framed windows. The property is set back from the main roadway with a garden area to the front with off road parking. Located approximately 30 miles from Stornoway town centre the village of Lemreway is on the east coast of Lewis. Amenities including shop, school and healthcare in the nearby villages of Kershader and Gravir approximately 5 Bathroom miles away. Sale of the croft is subject to Crofting Commission approval. Directions Travelling out of Stornoway town centre passing the Co-op superstore take the first turning to your left at the roundabout. Follow the roadway for approximately 16 miles travelling through the villages of Leurbost, Laxay and Balallan. At the end of Balallan turn to your left hand side and follow the roadway through the district of South Lochs for approximately 13 miles passing through Habost, Kershader, Garyvard and Gravir until you reach the village Lemreway. Continue straight ahead and travel approximately 0.8 miles. Number 2 Lemreway is the second last house on your right hand side. Bedroom 1 EPC BAND E Bedroom 2 Bedroom 3 Bedroom 4 Rear Aspect Croft and outbuilding View Plan description Porch 2.07m (6'9") x 1.59m (5'3") Vinyl flooring. -

Ciad Oileanaich Aig Roinn Na Ceiltis Oilthigh Ghlaschu

Ciad oileanaich aig Roinn na Ceiltis Oilthigh Ghlaschu Seisean / Session 1906-07 gu / to 1913-14. The first students of Celtic at the University of Glasgow An Oll. Urr. Seòras MacEanruig, ciad òraidiche an ceann oileanaich le Ceiltis an Oilthigh Ghlaschu bho 1906 gun do chaochail e, 1912. The Rev. George Henderson, first lecturer of Celtic as a degree subject, from 1906 until his death in 1912. (Dealbh bho Celtic Review, vol. VIII, 1912-13, 246-7) Oileanaich clàraichte airson clasaichean ann an Roinn na Ceiltis Students enrolled for Celtic classes Bho 1906 – 1907 gu 1913 – 1914 Air tharraing bho chlàraidhean ann an tasg lann an Oilthighe Based on records at Glasgow University Archive Services Class Catalogues (R9) & Matriculation Albums (R8) 1 Chaidh an liosta seo a dhealbh mar phàirt dhan phròiseact ‘Sgeul na Gàidhlig’ aig Roinn na Ceiltis is na Gàidhlig aig Oilthigh Ghlaschu. Tha mi gu mòr an comain stiùireadh agus comhairle luchd-obrach tasg lann Oilthigh Ghlaschu air son mo chuideachadh. Thathar gu mòr an comainn gach duine dhiubh sin ach fhuaireamaid taic agus stiùireadh sònraichte gu tusan bho Alma Topen, Kimberly Beasley agus Callum Morrison a tha uile cho mean-eòlach air stòrais an tasg-lann. Is ann ann am Beurla a tha na clàraidhean seo air fad, is leis gur ann, chaidh an cumail am Beurla airson soilleireachd. This list was compiled as part of the Sgeul na Gàidlig aig Oilthigh Ghlaschu (The story of Gaelic at the University of Glasgow) project. The sources are all in English and the names have been kept as they were originally recorded. -

Chris Ryan on Behalf of 52 Lewis and Harris Businesses – 3 April 2008

Submission from Chris Ryan on behalf of 52 Lewis and Harris businesses – 3 April 2008 Dear Sir/Madam 7-DAY FERRY SERVICES TO LEWIS & HARRIS The undersigned businesses, all based in the Western Isles, request that Sunday ferry services to Lewis & Harris should be introduced in the summer of 2008. This will be a necessary and long overdue development with the potential to improve the islands’ tourism industry in line with the Scottish Governments’ target of a 50% increase in tourism revenues. The proposed introduction of RET fares from October 2008 is also likely to result in increased demand and additional capacity will be needed to cope with peak season demand, particularly at weekends. However, our view as businesses is that Sunday services must be phased-in ahead of RET and that they should certainly be in place for summer 2008. Apart from the immediate boost for the local economy, this would give accommodation providers and tourism related businesses an indication of the response to weekend services and allow for business planning for the summer of 2009, which is the Year of Homecoming. Quite apart from the many social benefits, Sunday ferry services will make a major difference to the local economy by extending the tourist season, enabling businesses to work more efficiently and spreading visitor benefits throughout the islands. As a specific example, the Hebridean Celtic Festival, held in July, attracts over 15,000 people and contributes over £1m to the local economy. A Sunday ferry service would mean that many visitors to the festival would stay an extra night, enjoy all 4 –days of the festival and see more of the islands. -

The Norse Influence on Celtic Scotland Published by James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow

i^ttiin •••7 * tuwn 1 1 ,1 vir tiiTiv^Vv5*^M òlo^l^!^^ '^- - /f^K$ , yt A"-^^^^- /^AO. "-'no.-' iiuUcotettt>tnc -DOcholiiunc THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND PUBLISHED BY JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS, GLASGOW, inblishcre to the anibersitg. MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON. New York, • • The Macmillan Co. Toronto, • - • The Mactnillan Co. of Canada. London, • . - Simpkin, Hamilton and Co. Cambridse, • Bowes and Bowes. Edinburgh, • • Douglas and Foults. Sydney, • • Angus and Robertson. THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND BY GEORGE HENDERSON M.A. (Edin.), B.Litt. (Jesus Coll., Oxon.), Ph.D. (Vienna) KELLY-MACCALLUM LECTURER IN CELTIC, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW EXAMINER IN SCOTTISH GADHELIC, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY I9IO Is buaine focal no toic an t-saoghail. A word is 7nore lasting than the world's wealth. ' ' Gadhelic Proverb. Lochlannaich is ànnuinn iad. Norsemen and heroes they. ' Book of the Dean of Lismore. Lochlannaich thi'eun Toiseach bhiir sgéil Sliochd solta ofrettmh Mhamiis. Of Norsemen bold Of doughty mould Your line of oldfrom Magnus. '' AIairi inghean Alasdair Ruaidh. PREFACE Since ever dwellers on the Continent were first able to navigate the ocean, the isles of Great Britain and Ireland must have been objects which excited their supreme interest. To this we owe in part the com- ing of our own early ancestors to these isles. But while we have histories which inform us of the several historic invasions, they all seem to me to belittle far too much the influence of the Norse Invasions in particular. This error I would fain correct, so far as regards Celtic Scotland.