The Mayor Recognises That Street

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shifting Shopping Patterns Through Food Marketplace Platform: a Case Study in Major Cities of Indonesia

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 31 May 2021 doi:10.20944/preprints202105.0718.v1 Article SHIFTING SHOPPING PATTERNS THROUGH FOOD MARKETPLACE PLATFORM: A CASE STUDY IN MAJOR CITIES OF INDONESIA 1 2 3 Istianingsih * Islamiah Kamil robertus Suraji 1 Economics and Business Faculty, Universitas Bhayangkara Jakarta Raya, Kota Jakarta Selatan, Daerah Khusus Ibukota Jakarta 12550, Indonesia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] 2 Business and Social Science Faculty, Universitas Dian Nusantara. [email protected] 2 Computer Science Faculty, Universitas Bhayangkara Jakarta Raya, Kota Jakarta Selatan, Daerah Khusus Ibukota Jakarta 12550, Indonesia; [email protected] Abstract: The obligation to keep a distance from other people due to the pandemic has changed human life patterns, especially in shopping for their primary needs, namely food. The presence of the food marketplace presents new hope in maintaining health and food availability without crowding with other people while shopping. The main problem that is often a concern of the public when shopping online is transaction security and the Ease of use of this food marketplace applica- tion. This research is the intensity of using the Food Marketplace in terms of Interest, transaction security, and Ease of use of this application.Researchers analyzed the relationship between varia- bles with the Structural equation model. Respondents who became this sample were 300 applica- tion users spread across various major cities in Indonesia.This study's results provide a view that the intensity of the food marketplace's use has increased significantly during the new normal life. -

Taking the Borough Market Route: an Experimental Ethnography of the Marketplace

Taking the Borough Market Route: An Experimental Ethnography of the Marketplace Freek Janssens -- 0303011 Freek.Janssens©student.uva.nl June 2, 2008 Master's thesis in Cultural An thropology at the Universiteit van Amsterdam. Committee: dr. Vincent de Rooij (supervi sor), prof. dr. Johannes Fabian and dr. Gerd Baumann. The River Tharrws and the Ciiy so close; ihis mnst be an important place. With a confident but at ihe same time 1incertain feeling, I walk thrmigh the large iron gales with the golden words 'Borough Market' above il. Asphalt on the floor. The asphalt seems not to correspond to the classical golden letters above the gate. On the right, I see a painted statement on the wall by lhe market's .mpcrintendent. The road I am on is private, it says, and only on market days am [ allowed here. I look around - no market to sec. Still, I have lo pa8s these gales to my research, becanse I am s·upposed to meet a certain Jon hCTe today, a trader at the market. With all the stories I had heard abont Borongh Market in my head, 1 get confnsed. There is nothing more to see than green gates and stalls covered with blue plastic sheets behind them. I wonder if this can really turn into a lively and extremely popular market during the weekend. In the corner I sec a sign: 'Information Centre. ' There is nobody. Except from some pigeons, all I see is grey walls, a dirty roof, gates, closed stalls and waste. Then I see Jon. A man in his forties, small and not very thin, walks to me. -

Lumen De Lumine the NEWSLETTER of the MANILA OBSERVATORY

Lumen de Lumine THE NEWSLETTER OF THE MANILA OBSERVATORY Vol.1 Issue No. 2 | July-September 2018 What’s Inside University of Arizona Scientists visit Manila Observatory INSTRUMENT SET-UP–– Dr. Armin Sorooshian and three Lecture Series: of his PhD students, Alexis McDonald, Connor Stahl, and Aerosol Physics and Rachel Braun, from the University of Arizona visited the Manila Chemistry 2 Observatory last 17 July-01 August ahead of the implementation of the Cloud, Aerosols and Monsoon Processes Philippines Coastal Cities at Risk Experiment (CAMP2Ex) in 2019. Holds First National Conference 2 Dr. Sorooshian’s visit marked the beginning of CHECSM (CAMP2Ex Weather and Composition Monitoring), which is an National and intensive field campaign as a prelude to CAMP2Ex. International Participation The team from the University of Arizona set-up a micro-orifice uniform deposit impactor (MOUDI) at the Annex Building of Dr. Gemma Narisma the Manila Observatory. MOUDI presents a 12-stage cascade Gives Talk on Space- impactor that can segregate ultra-fine, fine, and coarse particulate Based information matter. The Observatory is classified as an urban-mix site which for Understanding will be able to paint a picture of aerosol characteristics coming Atmospheric Hazards from different sources. in Disaster Risk TOP: MOUDI Set-up at the Manila Observatory’s Annex Building 3 BOTTOM: UofA Researchers explain MOUDI to AQD-ITD and MO Data gathered in CHECSM will serve as a baseline measurement Staff (Photos from AQD-ITD) Regional Climate in an urban environment. MOUDI is set to measure air quality for Systems Laboratory in one year in the Observatory Grounds. -

Unlocking Potential What’S in This Report

Great Portland Estates plc Annual Report 2013 Unlocking potential What’s in this report 1. Overview 3. Financials 1 Who we are 68 Group income statement 2 What we do 68 Group statement of comprehensive income 4 How we deliver shareholder value 69 Group balance sheet 70 Group statement of cash flows 71 Group statement of changes in equity 72 Notes forming part of the Group financial statements 93 Independent auditor’s report 95 Wigmore Street, W1 94 Company balance sheet – UK GAAP See more on pages 16 and 17 95 Notes forming part of the Company financial statements 97 Company independent auditor’s report 2. Annual review 24 Chairman’s statement 4. Governance 25 Our market 100 Corporate governance 28 Valuation 113 Directors’ remuneration report 30 Investment management 128 Report of the directors 32 Development management 132 Directors’ responsibilities statement 34 Asset management 133 Analysis of ordinary shareholdings 36 Financial management 134 Notice of meeting 38 Joint ventures 39 Our financial results 5. Other information 42 Portfolio statistics 43 Our properties 136 Glossary 46 Board of Directors 137 Five year record 48 Our people 138 Financial calendar 52 Risk management 139 Shareholders’ information 56 Our approach to sustainability “Our focused business model and the disciplined execution of our strategic priorities has again delivered property and shareholder returns well ahead of our benchmarks. Martin Scicluna Chairman ” www.gpe.co.uk Great Portland Estates Annual Report 2013 Section 1 Overview Who we are Great Portland Estates is a central London property investment and development company owning over £2.3 billion of real estate. -

Mandaluyong City, Philippines

MANDALUYONG CITY, PHILIPPINES Case Study (Public Buildings) Project Summary: Manila, the capital of the Republic of the Philippines, has the eighteenth largest metropolitan area in the world, which includes fifteen cities and two municipalities. Mandaluyong City is the smallest city of the cities in Metro Manila, with an area of only twelve square kilometers and a population of over 278,000 people. A public market was located in the heart of Mandaluyong City, on a 7,500 square meters area along Kalentong Road, a main transit route. In 1991, the market was destroyed in a major fire, in large part because most of the structure was made of wood. As a temporary answer for the displaced vendors, the government allowed about 500 of them to set up stalls along the area’s roads and sidewalks. This rapidly proved to be impractical, in that it led to both traffic congestion and sanitation problems. Rebuilding the public market became a high priority for the city government, but financing a project with an estimated cost of P50 million was beyond the city’s capability. Local interest rates were high, averaging approximately 18 percent annually, and the city was not prepared to take on the additional debt that construction of a new market would have required. The city government was also concerned that if the charges to stall owners became too onerous, the increased costs would have to be passed on to their customers, many of whom were lower-income residents of the area. The answer to this problem that the city government decided to utilize was based on the Philippines’ national Build-Operate-Transfer law of 1991. -

(30.03.2015) Contents 1 Introduction and Context

SOMERS TOWN NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN : 2015 - 2025 TO SOMERS TOWN NEIGHBOURHOOD FORUM (30.03.2015) CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION AND CONTEXT 2 WHY DOES SOMERS TOWN NEED A NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN 3 WHO PREPARED THE PLAN 4 HOW THE PLAN WAS PREPARED 5 VISION AND AIM OF THE PLAN 6 POLICIES 6.1 ECONOMIC AND EMPLOYMENT POLICIES 6.2 MEANWHILE USES POLICIES 6.3 MOVEMENT POLICIES 6.4 HOUSING POLICIES 6.5 ENVIRONMENT AND GREEN SPACE POLICIES 6.6 COMMUNITY AND CULTURAL FACILITIES 7 HS2 and CR2 8 PROJECTS 9 DELIVERING THE NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN APPENDICES: 1. Somers Town profile 2. Neighbourhood BoundarY and Forum applications to LB Camden 3. Somers Town Neighbourhood Forum (STNF) Constitution 4. Expert support and advice 5. Timeline and bibliographY 6. Participating organisations and groups since 2011 7. Residents Housing and Open Space SurveY Findings 8. HS2 Petition 9. Somers Town Job Hub 10. CommunitY Cinema ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: 1 1. INTRODUCTION AND CONTEXT Somers Town Neighbourhood: Local planning context, Euston Area Plan (EAP)1 1.1 Somers Town Neighbourhood BoundarY Plan including part of Euston Area Plan boundarY (Plan 1) As Plan 1 indicates, Somers Town is clearly defined on 3 of its 4 sides By major road and rail infrastructure. As such it is an oBvious, geographical, neighBourhood. Somers Town’s southern boundary is Euston Road – part of the Inner city ring road (A 501). The Central Business District of London extends across the Euston Road into south Somers Town (between Phoenix Road and Euston Road) Immediately to the east lies the Kings Cross St Pancras Growth / Opportunity Area (international, national and metropolitan transport huB plus associated property development: Kings Cross Central). -

The Workplace Food Hall & the Future of the Company

THE WORKPLACE FOOD HALL & THE FUTURE OF THE COMPANY CAFETERIA Everyone loves great food. Over the past few decades, we’ve gone from a culture that placed a premium on meals of convenience — microwave dinners, fast food, anything that comes out of a box — to one that increasingly values delicious, high-quality food experiences. We no longer settle for whatever is easiest or cheapest. We now live in an age where people will happily drive miles out of their way to grab a gourmet grilled cheese from a food truck with great Yelp reviews. We also crave variety, authenticity, and value in our meals. Present us with a predictable and lackluster menu, and we notice. If the food isn’t great, we probably won’t come back if we have better options. That’s even true for those hurried meals we take during our lunch breaks at work. For legacy cafeteria providers, the consumer shift towards thoughtful, artisanal meals is becoming a serious problem. For legacy cafeteria The Global providers it was never Food Hall Trend about the food The idea behind the modern food hall is simple: Create a central place where people from all walks of life can come Countless companies have spent — and lost — a tremendous together to sample and taste their way through the best amount of money on their cafeterias. They’re losing more dishes an entire city has to offer. It works by turning an now than ever before. The reasons for this aren’t hard to otherwise underused space — often an empty section of a understand. -

Fernando Amorsolo's Marketplace During the Occupation Ms Clarissa

Fernando Amorsolo’s Marketplace during the Occupation Clarissa Chikiamco Curator, National Gallery Singapore 109 Figure 1. Fernando Amorsolo, Marketplace during the Occupation, 1942, oil on canvas, 57 by 82cm. Collection of National Gallery Singapore. World War II was a painful event globally and its events around him, he departed mostly from impact was felt no less in the region of Southeast his usual subject matters of idyllic images of the Asia. Te Japanese Occupation of several countries countryside, such as men and women planting in this part of the world led to innumerable rice, for which he had become well-known. instances of rape, torture and killings. While it was obviously a horrifying period, many artists In 1942, Japanese forces entered Manila, across the region felt compelled to respond – either immediately afer New Year’s Day. Amorsolo by painting during the war and documenting intriguingly chose to paint a market scene that what was happening, or reacting in retrospect frst year of the Japanese Occupation (Figure. 1), afer the war when there was sufcient time, quite diferent from the ruins he painted towards space and safety to re-engage in artistic practice. the end of the war or his theatrical scene of a Singapore’s National Collection encompasses male hero stalwartly defending a woman from various Southeast Asian works which capture rape by a Japanese soldier (Figures. 2 and 3). At the artists’ diferent responses to a shared frst glance, Marketplace during the Occupation historical experience. seemingly depicts a typical market scene, with vendors selling fruits and vegetables to interested Tree of these works are by one of the Philippines’ members of the public. -

10X10-2020-Catalogue-Article-25

European Painting 1850-1930 Adrian runs Adrian Biddell Fine Art Ltd, dealing in paintings and sculpture from a range of periods and specialising in European Painting 1850-1930. He sources works, arranges private sales, and offers both new and established collectors advice on buying, selling and valuations. A principal auctioneer at Sotheby’s for many years, he was a Senior Director in Impressionist and Modern art, before being appointed head of 19th century European paintings. WWW.ADRIANBIDDELL.COM [email protected] +44 (0) 7767 472735 Online Auction 30th October - 15th November UK & INTERNATIONAL www.article-25.org/10x10 INSTALLATION PACKING TRANSPORTATION STORAGE & SECURITY INSURANCE CONSERVATION +44 (0) 20 8682 0587 [email protected] CONSULTANCY www.artinstallationservices.co.uk Humanitarian Architecture Foreword As the global pandemic has restricted opportunities to meet together in a physical location, this year’s 10x10 is not taking place in the usual manner. Our 10th anniversary of this event was always going to be different – and this year we have embraced a digital platform to enable us to deliver the same high quality artwork, with some fantastic contributions, some from Royal Academicians and one from a celebrated street artist. I am sure you will enjoy browsing the online catalogue from the comfort of your own surroundings, placing bids as you engage with these wonderful artworks. We are indebted to all artists who have made contributions during our anniversary year. 10x10 brings together artists, architects, sculptors and designers, who create and donate artworks inspired by our day to day interaction with the built environment. Article 25 contributors often create a unique piece for the auction. -

7- NO 235. 236 237. NAME JACK YATES TITLE Kabarett in the Street Nude with Black Stockings Women with Open Gown MEDIUM Watercol

-7- NO NAME TITLE MEDIUM PRICE £ 235. JACK YATES Kabarett Watercolour 70 236 In the Street Watercolour 70 237. Nude with Black Stockings Papercut 120 238. Women with Open Gown Pencil 70 KATHLEEN GUTHRIE 1905-1981 Kathleen Guthrie studied at the Slade and Royal Academy Schools. Her earlier one-man exhibitions were held in the USA, where she and Robin Guthrie spent some time. Later she exhibited extensively in this country, both in mixed and one-man exhibitions. Her work was seen in the Royal Academy, the Whitechapel Art Gallery, Gimpel Fils, Redfern and many other venues. She was a member of the Hampstead Artists' Council for many years, a one time Vice-Chairman of the Women's International Art Club and a Fellow of the Free Painters Group. 239. Wilmington, Vermont, USA 9931 Oil Not for sale 240. The American Girl 1934 Oil Not for sale 241. Bathers at Cassis 1936 Gouache Not for sale 242. The Spy 1942 Oil Not for sale 243. The Bicycle Ride 1944 Oil Not for sale 2 44. Still Life with Flowers 1946 Gouache Not for sale 245. Brighton 1952 Gouache Not for sale 246. Mousehole, Cornwall 1956 Oil £180 247. Flowers and Fish 1958 Gouache £ 75 248. Extending 1959 Oil £240 249. Lismore Circus, NW5 1960 Tempera NFS 250. Flowerscape 1960 Gouache £ 85 251. The Tea Party 1961 Gouache £ 85 252. Swans on Hampstead Heath 1961 Gouache NFS 253. Surprise 1962 Silkscreen Print £ 65 £40 Unf 254. The Pianoplayer 1962 Gouache £ 85 255. In the Wood 1962 Oil NFS 256. Blue Picture 1962 Oil NFS 257. -

WIC Approved Vendors

WIC Approved Vendors Swipe Seperate County Store Name Address Type Card 1st WIC items Adair 212 SW Kent Street Greenfield IA 50849 Fareway Store #941 641-343-7091 Grocery 607 South Division Street Stuart IA 50250 Hometown Foods #0921 515-523-1772 Grocery Adams 300 - 10th Street Corning IA 50841 HyVee Food Store #1083 641-322-3010 Grocery Allamakee 777 11th Avenue SW Waukon IA 52172 Fareway Store #062 563-568-5017 Grocery 420 Main Street Lansing IA 52151 Lansing IGA 563-538-4774 Grocery 124 West Tilden Street Postville IA 52162 Quillin's Quality Foods 563-864-3621 Grocery 9 - 9th Street SW Waukon IA 52172 Quillin's Food Ranch 563-568-3316 Grocery Appanoose 609 North 18th Street Centerville IA 52544 HyVee Food Store #1058 641-856-3277 Grocery 305 South 18th Street Centerville IA 52544 Fareway Store #827 641-437-7064 Grocery 23145 Highway 5 Centerville IA 52544 Walmart Supercenter #1621 641-437-1212 Grocery Audubon 104 Market Street Audubon IA 50025 Audubon Foodland 712-563-2519 Grocery X X Benton 1206 - 7th Avenue Belle Plaine IA 52208 Country Foods 319-444-2624 Grocery 501 'A' Avenue Vinton IA 52349 Fareway Store #462 319-472-2861 Grocery Black Hawk 1956 Lafayette Waterloo IA 50703 Cork's Grocery 319-233-6785 Grocery X X 2302 West First Street Cedar Falls IA 50613 CVS Pharmacy #8538 319-277-5181 Pharmacy 1825 East San Marnan Drive Waterloo IA 50702 CVS Pharmacy #8544 319-235-6249 Pharmacy 205 Franklin Street Waterloo IA 50703 CVS Pharmacy #8546 319-234-4736 Pharmacy 215 South Evans Road Evansdale IA 50707 Fareway Store #067 319-287-5142 -

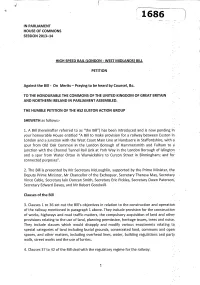

1686 HS2 Euston Action Group

r 1686 IN PARLIAMENT HOUSEOF COMMONS SESSION 2013-14 HIGH SPEED RAIL (LONDON - WEST MIDLANDS) BILL PETITION Against the Bill - On Merits - Praying to be heard by Counsel, &c. TOTHE HONOURABLETHE COMMONS OFTHE UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN AND NORTHERN IRELAND IN PARLIAMENT ASSEMBLED. THE HUMBLE PETITION OF THE HS2 EUSTON ACTION GROUP SHEWETH as follows:- 1. A Bill (hereinafter referred to as "the Bill") has been introduced and is now pending in your honourable House entitled "A Bill to make provision for a railway between Euston in London and a junction with the West Coast Main Line at Handsacre in Staffordshire, with a spur from Old Oak Common in the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham to a junction with the Channel Tunnel Rail Link at York Way in the London Borough of Islington and a spur from Water Orton in Warwickshire to Curzon Street in Birmingham; and for connected purposes". 2. The Bill is presented by Mr Secretary McLoughlin, supported by the Prime Minister, the Deputy Prime Minister, Mr Chancellor of the Exchequer, Secretary Theresa May, Secretary Vince Cable, Secretary lain Duncan Smith, Secretary Eric Pickles, Secretary Owen Paterson^ Secretary Edward Davey, and Mr Robert Goodwill. Clausesof the Bill 3. Clauses 1 to 36 set out the Bill's objectives in relation to the construction and operation ofthe railway mentioned in paragraph 1 above. They include provision for the construction of works, highways and road traffic matters, the compulsory acquisition of land and other provisions relating to the use of land, planning permission, heritage issues, trees and noise; They include clauses which would disapply and modify various enactments relating to special categories of land including burial grounds, consecrated land, commons and open spaces, and other matters, including overhead lines, water, building regulations and party walls, street works and the use of lorries.