Seabird Harvest in Iceland Aever Petersen, the Icelandic Institute of Natural History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Handbook of Siberia and Arctic Russia : Volume 1 : General

Presented to the UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO LIBRARY by the ONTARIO LEGISLATIVE LIBRARY 1980 I. D. 1207 »k.<i. 57182 g A HANDBOOK OF**' SIBERIA AND ARCTIC RUSSIA Volume I GENERAL 57182 Compiled by the Geographical Section of the Naval Intelligence Division, Naval Staff, Admiralty LONDON : PUBLISHED BY HIS MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE. To be purchased through any Bookseller or directly from H.M. STATIONERY OFFICE at the following addresses : Imperial House, Kingswav, London, W.C. 2, and 28 1 Abingdon Street, London, S. W. ; 37 Peter Street, Manchester ; 1 St. Andrew's Crescent, Cardiff ; 23 Forth Street, Edinburgh ; or from E. PONSONBY, Ltd., 116 Grafton Street, Dublin. Price 7s. 6d. net Printed under the authority of His Majesty's Stationery Office By Frederick Hall at the University Press, Oxford. NOTE The region covered in this Handbook includes besides Liberia proper, that part of European Russia, excluding Finland, which drains to the Arctic Ocean, and the northern part of the Central Asian steppes. The administrative boundaries of Siberia against European Russia and the Steppe provinces have been ignored, except in certain statistical matter, because they follow arbitrary lines through some of the most densely populated parts of Asiatic Russia. The present volume deals with general matters. The two succeeding volumes deal in detail respectively with western Siberia, including Arctic Russia, and eastern Siberia. Recent information about Siberia, even before the outbreak of war, was difficult to obtain. Of the remoter parts little is known. The volumes are as complete as possible up to 1914 and a few changes since that date have been noted. -

Media Guide 2020

MEDIA GUIDE 2020 Contents Welcome 05 Minstrel Stakes (Group 2) 54 2020 Fixtures 06 Jebel Ali Racecourse & Stables Anglesey Stakes (Group 3) 56 Race Closing 2020 08 Kilboy Estate Stakes (Group 2) 58 Curragh Records 13 Sapphire Stakes (Group 2) 60 Feature Races 15 Keeneland Phoenix Stakes (Group 1) 62 TRM Equine Nutrition Gladness Stakes (Group 3) 16 Rathasker Stud Phoenix Sprint Stakes (Group 3) 64 TRM Equine Nutrition Alleged Stakes (Group 3) 18 Comer Group International Irish St Leger Trial Stakes (Group 3) 66 Coolmore Camelot Irish EBF Mooresbridge Stakes (Group 2) 20 Royal Whip Stakes (Group 3) 68 Coolmore Mastercraftsman Irish EBF Athasi Stakes (Group 3) 22 Coolmore Galileo Irish EBF Futurity Stakes (Group 2) 70 FBD Hotels and Resorts Marble Hill Stakes (Group 3) 24 A R M Holding Debutante Stakes (Group 2) 72 Tattersalls Irish 2000 Guineas (Group 1) 26 Snow Fairy Fillies' Stakes (Group 3) 74 Weatherbys Ireland Greenlands Stakes (Group 2) 28 Kilcarn Stud Flame Of Tara EBF Stakes (Group 3) 76 Lanwades Stud Stakes (Group 2) 30 Round Tower Stakes (Group 3) 78 Tattersalls Ireland Irish 1000 Guineas (Group 1) 32 Comer Group International Irish St Leger (Group 1) 80 Tattersalls Gold Cup (Group 1) 34 Goffs Vincent O’Brien National Stakes (Group 1) 82 Gallinule Stakes (Group 3) 36 Moyglare Stud Stakes (Group 1) 84 Ballyogan Stakes (Group 3) 38 Derrinstown Stud Flying Five Stakes (Group 1) 86 Dubai Duty Free Irish Derby (Group 1) 40 Moyglare ‘Jewels’ Blandford Stakes (Group 2) 88 Comer Group International Curragh Cup (Group 2) 42 Loughbrown -

Steller's Sea

eptember 1741. Captain-commander Vitus Bering’s ship, St. Peter, was stumbling somewhere among the long desolate string of Aleutian Islands in the far North Pacific. All on board recognized that it was unlikely they’d ever make it home. Scurvy had flattened several of the crew, two men had already died, and Captain Bering himself was terribly ill. The fresh water stored in barrels was mostly foul, and the storm-force winds and seas were constantly in their faces. Sailing aboard St. Peter and sharing the cabin with Captain Bering was a German physician and naturalist Snamed Georg Wilhelm Steller. On his first voyage, Steller was certain they were near to land because he saw floating seaweed and various birds that he knew to be strictly coastal. But no one listened to him, in part because he hadn’t been shy in showing that he thought them all idiots, and also because his idea of exactly where they happened to be was wrong. Bering’s expedition continued, blindly groping westward toward Siberia’s Kamchatka Peninsula. The storms raged on, more men died, then eventually, somehow, they made it to a small protected harbor in the middle of the night. They hoped it was the mainland. Steller and his servant rowed several of the sickest men ashore the next morning. He thought the place was an island because of the shape of the clouds and how the sea otters carelessly swam over to the boat, unafraid of man. Once ashore, Steller noticed a huge animal swimming along the coast, a creature that he had never seen before and was unknown in cold, northern waters. -

Region Building and Identity Formation in the Baltic Sea Region

IJIS Volume 3 REGION BUILDING AND IDENTITY FORMATION IN THE BALTIC SEA REGION ∗ Imke Schäfer Abstract This paper examines the concept of “new region building” in the Baltic Sea region with emphasis on the construction of a collective “Baltic” identity. Possible implications of these processes on Russia as a non-EU member state are discussed. Region building around the Baltic Sea is conceptualised within the framework of social constructivism, and a connection between region building and identity formation is established. Furthermore, an attempt is made to shed light on the way in which a “Baltic identity” is promoted in the region. By means of a short discourse analysis, certain characteristics of the Baltic Sea region are discovered that are promoted as the basis for a regional identity by various regional actors. The impact of these characteristics on relations between Russia, the EU and the other Baltic Sea states are examined and conclusions are drawn in relation to the region building processes in the Baltic Sea area. INTRODUCTION Cooperation in the Baltic Sea region (BSR) has prospered since the independence of the Baltic States in the beginning of the 1990s. Several programmes and initiatives have been established, such as the Northern Dimension initiative (ND), the Council of Baltic Sea States (CBSS) or the Baltic Sea States Subregional Cooperation (BSSSC). The EU actively supports cooperation in this region. In 1997, at the Luxembourg European Council, Finland’s Northern Dimension initiative (ND) was recognized as part of the -

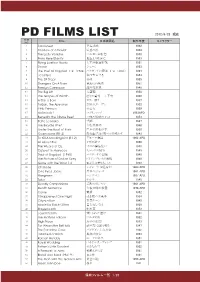

Pd Films List 0824

PD FILMS LIST 2012/8/23 現在 FILM Title 日本映画名 制作年度 キャラクター NO 1 Sabouteur 逃走迷路 1942 2 Shadow of a Doubt 疑惑の影 1943 3 The Lady Vanishe バルカン超特急 1938 4 From Here Etanity 地上より永遠に 1953 5 Flying Leather Necks 太平洋航空作戦 1951 6 Shane シェーン 1953 7 The Thief Of Bagdad 1・2 (1924) バクダッドの盗賊 1・2 (1924) 1924 8 I Confess 私は告白する 1953 9 The 39 Steps 39夜 1935 10 Strangers On A Train 見知らぬ乗客 1951 11 Foreign Correspon 海外特派員 1940 12 The Big Lift 大空輸 1950 13 The Grapes of Wirath 怒りの葡萄 上下有 1940 14 A Star Is Born スター誕生 1937 15 Tarzan, the Ape Man 類猿人ターザン 1932 16 Little Princess 小公女 1939 17 Mclintock! マクリントック 1963APD 18 Beneath the 12Mile Reef 12哩の暗礁の下に 1953 19 PePe Le Moko 望郷 1937 20 The Bicycle Thief 自転車泥棒 1948 21 Under The Roof of Paris 巴里の屋根の根 下 1930 22 Ossenssione (R1.2) 郵便配達は2度ベルを鳴らす 1943 23 To Kill A Mockingbird (R1.2) アラバマ物語 1962 APD 24 All About Eve イヴの総て 1950 25 The Wizard of Oz オズの魔法使い 1939 26 Outpost in Morocco モロッコの城塞 1949 27 Thief of Bagdad (1940) バクダッドの盗賊 1940 28 The Picture of Dorian Grey ドリアングレイの肖像 1949 29 Gone with the Wind 1.2 風と共に去りぬ 1.2 1939 30 Charade シャレード(2種有り) 1963 APD 31 One Eyed Jacks 片目のジャック 1961 APD 32 Hangmen ハングマン 1987 APD 33 Tulsa タルサ 1949 34 Deadly Companions 荒野のガンマン 1961 APD 35 Death Sentence 午後10時の殺意 1974 APD 36 Carrie 黄昏 1952 37 It Happened One Night 或る夜の出来事 1934 38 Cityzen Ken 市民ケーン 1945 39 Made for Each Other 貴方なしでは 1939 40 Stagecoach 駅馬車 1952 41 Jeux Interdits 禁じられた遊び 1941 42 The Maltese Falcon マルタの鷹 1952 43 High Noon 真昼の決闘 1943 44 For Whom the Bell tolls 誰が為に鐘は鳴る 1947 45 The Paradine Case パラダイン夫人の恋 1942 46 I Married a Witch 奥様は魔女 -

Runde Miljøsenter: North Atlantic Seabird Seminar

North Atlantic Seabird Seminar – Fosnavåg, Norway 20-21 April 2015 Michael Hundeide (ed.) Runde Environmental Centre In cooperation with: Birdlife Norway (NOF) and Norwegian Biologist Association (BiO). Distribution: Open/Closed Runde Miljøsenter AS Client(s) 6096 Runde Org. Nr. 987 410 752 MVA Telephone: +47 70 08 08 00 E-mail: [email protected] Date: Web: www.rundesenteret.no 18.09.2015 Report Runde Miljøsenter Norsk: Nordatlantisk sjøfuglseminar 2015. Fosnavåg 20. og 21. April Rapportnummer: English: North Atlantic Seabird Seminar – Fosnavåg, Norway 20-21 April 2015 Author(s): Number of pages: Michael Hundeide (ed.) 52 Key words: Seabird ecology, Runde, North Atlantic, sand eel Sammendrag (Norsk):Rapporten er en gjengivelse av de temaer som ble presentert og diskutert på det internasjonale sjøfuglseminaret i Fosnavåg 20. og 21. april 2015: En rekke sjøfuglbestander har hatt en drastisk tilbakegang på Runde i senere år. Særlig gjelder dette artene: Krykkje, havhest, toppskarv, lomvi, alke, lunde m.fl. Med unntak av havsule, storjo og havørn som har hatt en økende tendens, har så å si samtlige av de andre sjøfuglartene gått ned. Denne situasjonen er ikke enestående for Runde og Norge, samme tendens gjør seg også gjeldende i Storbritannia, på Island og i hele Nordøst -Atlanteren. Selv om årsakene til krisen hos sjøfuglene er sammensatte og komplekse, var de fleste innleggsholderne enige om følgende punkter: 1) En vesentlig del av årsaken til krisen for sjøfuglbestandene på Runde og i Nordøst-Atlanteren skyldes mangel på egnet energirik mat (fettrik fisk av rett størrelse særlig tobis i Skottland, Færøyene og Sør-Vestlige Island) i hekkesesongen. Dette kan i sin tur forklares som en indirekte effekt av en liten økning i gjennomsnittstemperatur i havet. -

Early Maritime Russia and the North Pacific Arc Dianne Meredith Russia Has Always Held an Ambiguous Position in World Geography

Early Maritime Russia and the North Pacific Arc Dianne Meredith Russia has always held an ambiguous position in world geography. Like most other great powers, Russia spread out from a small, original core area of identity. The Russian-Kievan core was located west of the Ural Mountains. Russia’s earlier history (1240-1480) was deeply colored by a Mongol-Tatar invasion in the thirteenth century. By the time Russia cast off Mongol rule, its worldview had developed to reflect two and one-half centuries of Asiatic rather than European dominance, hence the old cliché, scratch a Russian and you find a Tatar. This was the beginning of Russia’s long search of identity as neither European nor Asian, but Eurasian. Russia has a longer Pacific coastline than any other Asian country, yet a Pacific identity has been difficult to assume, in spite of over four hundred years of exploration (Map 1). Map 1. Geographic atlas of the Russian Empire (1745), digital copy by the Russian State Library. Early Pacific Connections Ancient peoples from what is now present-day Russia had circum-Pacific connections via the North Pacific arc between North America and Asia. Today this arc is separated by a mere fifty-six miles at the Bering Strait, but centuries earlier it was part of a broad subcontinent more than one-thousand miles long. Beringia, as it is now termed, was not fully glaciated during the Pleistocene Ice Age; in fact, there was not any area of land within one hundred miles of the Bering Strait itself that was completely glaciated within the last million years, while for much of that time a broad band of ice to the east covered much of present-day Alaska. -

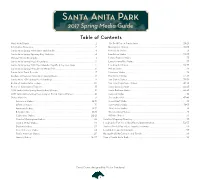

Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance

Santa Anita Park 2017 Spring Media Guide Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance . 2 The Gold Cup at Santa Anita . 28-29 Information Resources . 3 Honeymoon Stakes . 30-31 Santa Anita Spring Attendance and Handle . 4 Kona Gold Stakes . 31 Santa Anita Spring Opening Day Statistics . 4 Landaluce Stakes . 32-33 Michael Wrona Biography . 4 Lazaro Barrera Stakes . 33 Santa Anita Spring Meet Attendance . 5 Lennyfrommalibu Stakes . 33 Santa Anita Spring 2016 Meet Handle, Payoffs & Top Five Days . 5 Los Angeles Stakes . 34-35 Santa Anita Spring Meet Annual Media Poll . 6 Melair Stakes . 36 Santa Anita Track Records . 7 Monrovia Stakes . 36 Leaders at Previous Santa Anita Spring Meets . 8 Precisionist Stakes . 37-38 Santa Anita 2016 Spring Meet Standings . 9 San Carlos Stakes . 38-39 Roster of Santa Anita Jockeys . 10 San Juan Capistrano Stakes . 40-41 Roster of Santa Anita Trainers . 11 Santa Anita Juvenile . 42-43 2016 Santa Anita Spring Meet Stakes Winners . 12 Santa Barbara Stakes . 44-45 2016 Santa Anita Spring Meet Longest Priced Stakes Winners . 12 Senorita Stakes . 46 Stakes Histories . 13 Shoemaker Mile . 47-48 Adoration Stakes . 14-15 Snow Chief Stakes . 49 Affirmed Stakes . 15 Summertime Oaks . 50-51 American Stakes . 16-17 Thor's Echo Stakes . 51 Beholder Mile . 18-19 Thunder Road Stakes . 51 Californian Stakes . 20-21 Wilshire Stakes . 52 Charles Whittingham Stakes . 22 Satellite Wagering Directory . 53 Crystal Water Stakes . 23 Los Angeles Turf Inc . Club Officers/Administration . 54-55 Daytona Stakes . 23 Visitors Guide/Map of Los Angeles Freeways . 56 Desert Stormer Stakes . 24 Local Hotels and Restaurants . -

Russia and Siberia: the Beginning of the Penetration of Russian People Into Siberia, the Campaign of Ataman Yermak and It’S Consequences

The Aoyama Journal of International Politics, Economics and Communication, No. 106, May 2021 CCCCCCCCC Article CCCCCCCCC Russia and Siberia: The Beginning of the Penetration of Russian People into Siberia, the Campaign of Ataman Yermak and it’s Consequences Aleksandr A. Brodnikov* Petr E. Podalko** The penetration of the Russian people into Siberia probably began more than a thousand years ago. Old Russian chronicles mention that already in the 11th century, the northwestern part of Siberia, then known as Yugra1), was a “volost”2) of the Novgorod Land3). The Novgorod ush- * Associate Professor, Novosibirsk State University ** Professor, Aoyama Gakuin University 1) Initially, Yugra was the name of the territory between the mouth of the river Pechora and the Ural Mountains, where the Finno-Ugric tribes historically lived. Gradually, with the advancement of the Russian people to the East, this territorial name spread across the north of Western Siberia to the river Taz. Since 2003, Yugra has been part of the offi cial name of the Khanty-Mansiysk Autonomous Okrug: Khanty-Mansiysk Autonomous Okrug—Yugra. 2) Volost—from the Old Russian “power, country, district”—means here the territo- rial-administrative unit of the aboriginal population with the most authoritative leader, the chief, from whom a certain amount of furs was collected. 3) Novgorod Land (literally “New City”) refers to a land, also known as “Gospodin (Lord) Veliky (Great) Novgorod”, or “Novgorod Republic”, with its administrative center in Veliky Novgorod, which had from the 10th century a tendency towards autonomy from Kiev, the capital of Ancient Kievan Rus. From the end of the 11th century, Novgorod de-facto became an independent city-state that subdued the entire north of Eastern Europe. -

Drydocks World Dubai

G<CK75G=B;H<9@5H9GH89J9@CDA9BHG=BA5F=B9A5=BH9B5B79<5F8K5F9 GC:HK5F95B8H97<BC@C;=9G SEPTEMBER 2012 Exclusive interview: Drydocks World Dubai Gas turbines Extend maintenance intervals without affecting performance How to maintain climate specialist vessels during operation Australian Navy A new service regime to keep the fleet afloat Offshore wind farms Overcoming logistic challenges C ICEBREAKERS Climate specialist vessels Break the ice It’s not just the harsh weather that makes it difficult to protect and maintain climate specialist vessels Neil Jones, Marine Maintenance Technology International aintaining icebreaking and ice strengthened vessels does, as you might expect, have its Mchallenges. For a start, the nature of the way they operate subjects them to a huge amount of vibration, not to mention the impact of constantly operating in harsh weather. But conversely, as Albert Hagander, technical manager of the Swedish Maritime Administration’s Shipping Management Department, points out, there is actually a weather-related advantage in that the vessels are not usually in service during the summer. “You really can’t do much when they’re in service simply because of the weather conditions, often with ice on deck,” he points out. “In the summer, it’s often a better situation than with a conventional vessel, as you have the time to work on them while they’re alongside the dock or even in dry dock.” The Administration operates four big icebreakers plus a slightly smaller one for Lake Vänern that supplements the capability during the early or late season. That the icebreakers are vital can be seen from the fact that 95% of Swedish export/import trade is seaborne. -

FRAMEWORK for a CIRCUMPOLAR ARCTIC SEABIRD MONITORING NETWORK Caffs CIRCUMPOLAR SEABIRD GROUP Acknowledgements I

Supporting Publication to the Circumpolar Biodiversity Monitoring Program CAFF CBMP Report No. 15 September 2008 FRAMEWORK FOR A CIRCUMPOLAR ARCTIC SEABIRD MONITORING NETWORK CAFFs CIRCUMPOLAR SEABIRD GROUP Acknowledgements i CAFF Designated Agencies: t Environment Canada, Ottawa, Canada t Finnish Ministry of the Environment, Helsinki, Finland t Ministry of the Environment and Nature, Greenland Homerule, Greenland (Kingdom of Denmark) t Faroese Museum of Natural History, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands (Kingdom of Denmark) t Icelandic Institute of Natural History, Reykjavik, Iceland t Directorate for Nature Management, Trondheim, Norway t Russian Federation Ministry of Natural Resources, Moscow, Russia t Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, Stockholm, Sweden t United States Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Anchorage, Alaska This publication should be cited as: Aevar Petersen, David Irons, Tycho Anker-Nilssen, Yuri Ar- tukhin, Robert Barrett, David Boertmann, Carsten Egevang, Maria V. Gavrilo, Grant Gilchrist, Martti Hario, Mark Mallory, Anders Mosbech, Bergur Olsen, Henrik Osterblom, Greg Robertson, and Hall- vard Strøm (2008): Framework for a Circumpolar Arctic Seabird Monitoring Network. CAFF CBMP Report No.15 . CAFF International Secretariat, Akureyri, Iceland. Cover photo: Recording Arctic Tern growth parameters at Kitsissunnguit West Greenland 2004. Photo by Carsten Egevang/ARC-PIC.COM. For more information please contact: CAFF International Secretariat Borgir, Nordurslod 600 Akureyri, Iceland Phone: +354 462-3350 Fax: +354 462-3390 Email: ca"@ca".is Internet: http://www.ca".is ___ CAFF Designated Area Editor: Aevar Petersen Design & Layout: Tom Barry Institutional Logos CAFFs Circumpolar Biodiversity Monitoring Program: Framework for a Circumpolar Arctic Seabird Monitoring Network Aevar Petersen, David Irons, Tycho Anker-Nilssen, Yuri Artukhin, Robert Barrett, David Boertmann, Carsten Egevang, Maria V. -

Galloping Onto the Throne: Queen Elizabeth I and the Symbolism of the Horse

Heidegger 1 Galloping onto the Throne: Queen Elizabeth I and the Symbolism of the Horse University of California, San Diego, Department of History, Undergraduate Honors Thesis By: Hannah von Heidegger Advisor: Ulrike Strasser, Ph.D. April 2019 Heidegger 2 Introduction As she prepared for the impending attack of the Spanish Armada, Queen Elizabeth I of England purportedly proclaimed proudly while on horseback to her troops, “I know I have the body but of a weak and feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too.”1 This line superbly captures the two identities that Elizabeth had to balance as a queen in the early modern period: the limitations imposed by her sex and her position as the leader of England. Viewed through the lens of stereotypical gender expectations in the early modern period, these two roles appear incompatible. Yet, Elizabeth I successfully managed the unique path of a female monarch with no male counterpart. Elizabeth was Queen of England from the 17th of November 1558, when her half-sister Queen Mary passed away, until her own death from sickness on March 24th, 1603, making her one of England’s longest reigning monarchs. She deliberately avoided several marriages, including high-profile unions with Philip II of Spain, King Eric of Sweden, and the Archduke Charles of Austria. Elizabeth’s position in her early years as ruler was uncertain due to several factors: a strong backlash to the rise of female rulers at the time; her cousin Mary Queen of Scots’ Catholic hereditary claim; and her being labeled a bastard by her father, Henry VIII.