People V. Buchanan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Guide 2020

MEDIA GUIDE 2020 Contents Welcome 05 Minstrel Stakes (Group 2) 54 2020 Fixtures 06 Jebel Ali Racecourse & Stables Anglesey Stakes (Group 3) 56 Race Closing 2020 08 Kilboy Estate Stakes (Group 2) 58 Curragh Records 13 Sapphire Stakes (Group 2) 60 Feature Races 15 Keeneland Phoenix Stakes (Group 1) 62 TRM Equine Nutrition Gladness Stakes (Group 3) 16 Rathasker Stud Phoenix Sprint Stakes (Group 3) 64 TRM Equine Nutrition Alleged Stakes (Group 3) 18 Comer Group International Irish St Leger Trial Stakes (Group 3) 66 Coolmore Camelot Irish EBF Mooresbridge Stakes (Group 2) 20 Royal Whip Stakes (Group 3) 68 Coolmore Mastercraftsman Irish EBF Athasi Stakes (Group 3) 22 Coolmore Galileo Irish EBF Futurity Stakes (Group 2) 70 FBD Hotels and Resorts Marble Hill Stakes (Group 3) 24 A R M Holding Debutante Stakes (Group 2) 72 Tattersalls Irish 2000 Guineas (Group 1) 26 Snow Fairy Fillies' Stakes (Group 3) 74 Weatherbys Ireland Greenlands Stakes (Group 2) 28 Kilcarn Stud Flame Of Tara EBF Stakes (Group 3) 76 Lanwades Stud Stakes (Group 2) 30 Round Tower Stakes (Group 3) 78 Tattersalls Ireland Irish 1000 Guineas (Group 1) 32 Comer Group International Irish St Leger (Group 1) 80 Tattersalls Gold Cup (Group 1) 34 Goffs Vincent O’Brien National Stakes (Group 1) 82 Gallinule Stakes (Group 3) 36 Moyglare Stud Stakes (Group 1) 84 Ballyogan Stakes (Group 3) 38 Derrinstown Stud Flying Five Stakes (Group 1) 86 Dubai Duty Free Irish Derby (Group 1) 40 Moyglare ‘Jewels’ Blandford Stakes (Group 2) 88 Comer Group International Curragh Cup (Group 2) 42 Loughbrown -

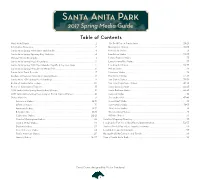

Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance

Santa Anita Park 2017 Spring Media Guide Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance . 2 The Gold Cup at Santa Anita . 28-29 Information Resources . 3 Honeymoon Stakes . 30-31 Santa Anita Spring Attendance and Handle . 4 Kona Gold Stakes . 31 Santa Anita Spring Opening Day Statistics . 4 Landaluce Stakes . 32-33 Michael Wrona Biography . 4 Lazaro Barrera Stakes . 33 Santa Anita Spring Meet Attendance . 5 Lennyfrommalibu Stakes . 33 Santa Anita Spring 2016 Meet Handle, Payoffs & Top Five Days . 5 Los Angeles Stakes . 34-35 Santa Anita Spring Meet Annual Media Poll . 6 Melair Stakes . 36 Santa Anita Track Records . 7 Monrovia Stakes . 36 Leaders at Previous Santa Anita Spring Meets . 8 Precisionist Stakes . 37-38 Santa Anita 2016 Spring Meet Standings . 9 San Carlos Stakes . 38-39 Roster of Santa Anita Jockeys . 10 San Juan Capistrano Stakes . 40-41 Roster of Santa Anita Trainers . 11 Santa Anita Juvenile . 42-43 2016 Santa Anita Spring Meet Stakes Winners . 12 Santa Barbara Stakes . 44-45 2016 Santa Anita Spring Meet Longest Priced Stakes Winners . 12 Senorita Stakes . 46 Stakes Histories . 13 Shoemaker Mile . 47-48 Adoration Stakes . 14-15 Snow Chief Stakes . 49 Affirmed Stakes . 15 Summertime Oaks . 50-51 American Stakes . 16-17 Thor's Echo Stakes . 51 Beholder Mile . 18-19 Thunder Road Stakes . 51 Californian Stakes . 20-21 Wilshire Stakes . 52 Charles Whittingham Stakes . 22 Satellite Wagering Directory . 53 Crystal Water Stakes . 23 Los Angeles Turf Inc . Club Officers/Administration . 54-55 Daytona Stakes . 23 Visitors Guide/Map of Los Angeles Freeways . 56 Desert Stormer Stakes . 24 Local Hotels and Restaurants . -

Galloping Onto the Throne: Queen Elizabeth I and the Symbolism of the Horse

Heidegger 1 Galloping onto the Throne: Queen Elizabeth I and the Symbolism of the Horse University of California, San Diego, Department of History, Undergraduate Honors Thesis By: Hannah von Heidegger Advisor: Ulrike Strasser, Ph.D. April 2019 Heidegger 2 Introduction As she prepared for the impending attack of the Spanish Armada, Queen Elizabeth I of England purportedly proclaimed proudly while on horseback to her troops, “I know I have the body but of a weak and feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too.”1 This line superbly captures the two identities that Elizabeth had to balance as a queen in the early modern period: the limitations imposed by her sex and her position as the leader of England. Viewed through the lens of stereotypical gender expectations in the early modern period, these two roles appear incompatible. Yet, Elizabeth I successfully managed the unique path of a female monarch with no male counterpart. Elizabeth was Queen of England from the 17th of November 1558, when her half-sister Queen Mary passed away, until her own death from sickness on March 24th, 1603, making her one of England’s longest reigning monarchs. She deliberately avoided several marriages, including high-profile unions with Philip II of Spain, King Eric of Sweden, and the Archduke Charles of Austria. Elizabeth’s position in her early years as ruler was uncertain due to several factors: a strong backlash to the rise of female rulers at the time; her cousin Mary Queen of Scots’ Catholic hereditary claim; and her being labeled a bastard by her father, Henry VIII. -

Seabird Harvest in Iceland Aever Petersen, the Icelandic Institute of Natural History

CAFF Technical Report No. 16 September 2008 SEABIRD HARVEST IN THE ARCTIC CAFFs CIRCUMPOLAR SEABIRD GROUP Acknowledgements CAFF Designated Agencies: • Directorate for Nature Management, Trondheim, Norway • Environment Canada, Ottawa, Canada • Faroese Museum of Natural History, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands (Kingdom of Denmark) • Finnish Ministry of the Environment, Helsinki, Finland • Icelandic Institute of Natural History, Reykjavik, Iceland • Ministry of the Environment and Nature, Greenland Homerule, Greenland (Kingdom of Denmark) • Russian Federation Ministry of Natural Resources, Moscow, Russia • Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, Stockholm, Sweden • United States Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Anchorage, Alaska This publication should be cited as: Merkel, F. and Barry, T. (eds.) 2008. Seabird harvest in the Arctic. CAFF International Secretariat, Circumpolar Seabird Group (CBird), CAFF Technical Report No. 16. Cover photo (F. Merkel): Thick-billed murres, Saunders Island, Qaanaaq, Greenland. For more information please contact: CAFF International Secretariat Borgir, Nordurslod 600 Akureyri, Iceland Phone: +354 462-3350 Fax: +354 462-3390 Email: [email protected] Internet: http://www.caff.is ___ CAFF Designated Area Editing: Flemming Merkel and Tom Barry Design & Layout: Tom Barry Seabird Harvest in the Arctic Prepared by the CIRCUMPOLAR SEABIRD GROUP (CBird) CAFF Technical Report No. 16 September 2008 List of Contributors Aever Petersen John W. Chardine The Icelandic Institute of Natural History Wildlife Research Division Hlemmur 3, P.O. Box 5320 Environment Canada IS-125 Reykjavik, ICELAND P.O. Box 6227 Email: [email protected], Tel: +354 5 900 500 Sackville, NB E4L 4K2 CANADA Bergur Olsen Email: [email protected], Tel: +1-506-364-5046 Faroese Fisheries Laboratory Nóatún 1, P.O. -

A Gray Horse Galileo (Ire)

NORTHERN DANCER SADLER'S WELLS (CAN) (USA) FAIRY BRIDGE (USA) GALILEO (IRE) MISWAKI (USA) URBAN SEA (USA) CAPRI (IRE) ALLEGRETTA (GB) (2014) A GRAY HORSE DANZIG (USA) ANABAA (USA) BALBONELLA (FR) DIALAFARA (FR) (2007) LINAMIX (FR) DIAMILINA (FR) DIAMONAKA (FR) CAPRI (IRE), Champion 3yr old stayer in Europe in 2017 and 2nd top rated 3yr old colt in Ireland in 2017, won 6 races at 2 to 4 years and £1,568,947 including Irish Derby, Curragh, Gr.1, St. Leger Stakes, Doncaster, Gr.1, Beresford Stakes, Curragh, Gr.2, Toals.com Bookmakers Alleged Stakes, Naas, Gr.3, Coolmore El Gran Senor Stakes, Tipperary, L., placed 8 times including third in Criterium de Saint-Cloud, Saint Cloud, Gr.1, Derrinstown Stud Derby Trial, Leopardstown, Gr.3, Loughbrown Stakes, Curragh, Gr.3, Saval Beg Levmoss Stakes, Leopardstown, L., fourth in QIPCO Champion Stakes, Ascot, Gr.1, Irish St. Leger Trial, Curragh, Gr.3, P.W. McGrath Memorial Ballysax Stakes, Leopardstown, Gr.3; Own brother to PASSION (IRE), CYPRESS CREEK (IRE) 1st Dam DIALAFARA (FR) (by Anabaa (USA)), won 1 race at 3 years and £10,622, placed once. Dam of six winners including: CAPRI (IRE) (2014 c. by Galileo (IRE)), See above. PASSION (IRE) (2017 f. by Galileo (IRE)), won 2 races at 2 and 3 years, 2020 and £150,465 including Irish Stallion Farms E.B.F. Stanerra Stakes, Naas, Gr.3, placed 6 times viz third in Juddmonte Irish Oaks, Curragh, Gr.1, QIPCO British Champions Fillies & Mares Stakes, Ascot, Gr.1, Ribblesdale Stakes, Ascot, Gr.2, Comer Group International Curragh Cup, Curragh, Gr.2, Irish Stallion Farms E.B.F. -

2020 International List of Protected Names

INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (only available on IFHA Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 03/06/21 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne-Billancourt, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org The list of Protected Names includes the names of : Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally renowned, either as main stallions and broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or jump) From 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine following international races : South America : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil Asia : Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup Europe : Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes North America : Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf Since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous following international races : South America : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil Asia : Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup Europe : Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion North America : Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf The main stallions and broodmares, registered on request of the International Stud Book Committee (ISBC). Updates made on the IFHA website The horses whose name has been protected on request of a Horseracing Authority. Updates made on the IFHA website * 2 03/06/2021 In 2020, the list of Protected -

Alkumait Best in the Mill Reef Cont

SUNDAY, 20 SEPTEMBER 2020 ARMSTRONGS IN LINE FOR PROFITABLE SALE ALKUMAIT BEST IN By Alayna Cullen THE MILL REEF There is a general feeling of relief this year that the yearling sales are taking place at all. While some of the key indices are down on previous years there is comfort to be found in the strong clearance rates experienced at the sales thus far and even more comfort to be taken by some of the results pinhookers have had from their investments of 2019. For siblings Chris and Tara Armstrong this year could be one of the more memorable ones for their young pinhooking operation from Beechvale Stud. At the upcoming Tattersalls Ireland September Yearling Sale they offer two yearling colts. The first is lot 107, a son of Profitable (Ire) whose first crop has been well received in the ring. The second is lot 222, who has arguably received one of the best pedigree updates since catalogue was printed. Cont. p9 Alkumait is another talented son of Showcasing for Sheikh Hamdan and Marcus Tregoning | racingfotos.com IN TDN AMERICA TODAY Sheikh Hamdan bin Rashid Al Maktoum=s twice-raced ‘STARSHIP’ BLASTS OFF IN WOODBINE MILE Alkumait (GB) (Showcasing {GB}) broke through tackling six Starship Jubilee punches her ticket to the GI Breeders’ Cup Mile furlongs in a July 28 Goodwood maiden and continued his when besting the boys in the $1-million Woodbine Mile Saturday. upward path with a decisive victory returning in Saturday=s Click or tap here to go straight to TDN America. G2 Dubai Duty Free Mill Reef S. -

Lot Sexe Père Père De Père Mère Père De Mère 480 M. SAKHEE BAHRI a Lulu Ofa Menifee MENIFEE 750 F. SIR PERCY MARK of ESTEE

FOALS ISSUS DE MERE BLACK-TYPE Lot Sexe Père Père de Père Mère Père de Mère 480 M. SAKHEE BAHRI A Lulu Ofa Menifee MENIFEE 750 F. SIR PERCY MARK OF ESTEEM Acenanga ACATENANGO 202 M. DALAKHANI DARSHAAN ALAVA ANABAA 754 F. ARCHANGE D'OR DANEHILL Alharixa LINAMIX 216 F. ELUSIVE CITY ELUSIVE QUALITY AUBONNE MONSUN 220 M. ARCH KRIS S BAHAMA MAMA INVINCIBLE SPIRIT 768 M. LAWMAN INVINCIBLE SPIRIT BASSE BESOGNE PURSUIT OF LOVE 507 M. KENTUCKY DYNAMITE KINGMAMBO Bits of Paradise DESERT PRINCE 229 M. MOUNT NELSON ROCK OF GIBRALTAR Blue Ciel OASIS DREAM 772 F. ASTRONOMER ROYAL DANZIG Bouboulina GRAND LODGE 520 F. ASTRONOMER ROYAL DANZIG Cobblestone Road GRINDSTONE 259 M. WHIPPER MIESQUE'S SON DINER DE LUNE BE MY GUEST 789 F. SLICKLY LINAMIX Dona Bella HIGHEST HONOR 793 F. LAWMAN INVINCIBLE SPIRIT Enigma SHARP VICTOR 559 F. ARTISTE ROYAL DANEHILL Freedom Flame DARSHAAN 293 M. PEINTRE CELEBRE NUREYEV Hitra LANGFUHR 582 M. SADDEX SADLER'S WELLS Irish Flower ZIETEN 809 F. ZAMBEZI SUN DANSILI John Quatz JOHANN QUATZ 186 F. ELUSIVE CITY ELUSIVE QUALITY JOINT ASPIRATION PIVOTAL 318 M. WHIPPER MIESQUE'S SON Lanciana ACATENANGO 320 F. ASTRONOMER ROYAL DANZIG Lazy Afternoon HAWK WING 323 F. SLICKLY LINAMIX LIGHT STEP NUREYEV 324 F. MYBOYCHARLIE DANETIME LINDSEY'S WISH TRIPPI 329 M. AZAMOUR NIGHT SHIFT LUNA ROYALE ROYAL APPLAUSE 333 F. TERTULLIAN MISWAKI Macina PLATINI 352 F. LE HAVRE NOVERRE Miss Mission SECOND EMPIRE 355 F. ROCK OF GIBRALTAR DANEHILL Music House SINGSPIEL 653 M. SEVRES ROSE CAERLEON Première Chance LINAMIX 654 M. COUNTRY REEL DANZIG PRETTY DARSHAAN 658 M. -

Sea Moon (GB) A+ Based on the Cross of Sadler's Wells and His Sons/Alleged Variant = 6.45 Breeder: Juddmonte Farms Ltd

11/01/11 11:47:20 EDT Sea Moon (GB) A+ Based on the cross of Sadler's Wells and his sons/Alleged Variant = 6.45 Breeder: Juddmonte Farms Ltd. (GB) =Nearco (ITY), 35 br Nearctic, 54 br *Lady Angela, 44 ch Northern Dancer, 61 b Native Dancer, 50 gr Natalma, 57 b Almahmoud, 47 ch Sadler's Wells, 81 b Hail to Reason, 58 br Bold Reason, 68 b Lalun, 52 b Fairy Bridge, 75 b *Forli, 63 ch Special, 69 b Thong, 64 b Beat Hollow (GB), 97 b Northern Dancer, 61 b Lyphard, 69 b Goofed, 60 ch Dancing Brave, 83 b Drone, 66 gr Navajo Princess, 74 b Olmec, 66 ch $Wemyss Bight (GB), 90 b Never Bend, 60 dk b Mill Reef, 68 b Milan Mill, 62 b =Bahamian (IRE), 85 ch =Busted (GB), 63 b =Sorbus (IRE), 75 b Censorship, 69 ch Sea Moon (GB) Bay Colt *Ribot, 52 b Foaled Mar 06, 2008 Tom Rolfe, 62 b in Great Britain Pocahontas, 55 br Hoist the Flag, 68 b War Admiral, 34 br Wavy Navy, 54 b *Triomphe, 47 b Alleged, 74 b *Princequillo, 40 b Prince John, 53 ch Not Afraid, 48 dk b Princess Pout, 66 b Determine, 51 gr Determined Lady, 59 dk b Tumbling, 53 b Eva Luna, 92 b *Herbager, 56 b =Appiani II (ITY), 63 b =Angela Rucellai (ITY), 54 *Star Appeal, 70 b b =Neckar (GER), 48 gr =Sterna (GER), 60 br Media Luna (GB), 81 b =Stammesart (GER), 44 b =Wild Risk (FR), 40 b =Vimy (FR), 52 b =Mimi, 43 b =Sounion (GB), 61 b *My Babu, 45 b =Esquire Girl (GB), 52 b =Lady Sybil (GB), 40 b Note on terminology in this report: Direct Cross refers to Dosage Profile: 4 2 12 5 1 Inbreeding: Northern Dancer: 3S X 5S Dosage Index: 1.00 the exact sire over exact broodmare sire; Rated Cross is Center of Distribution: +0.12 the cross used to base the TrueNicks rating and may differ from the direct cross to maintain statistical significance; AEI: Average Earnings Index; AWD: Average Winning Distance (in furlongs). -

To Consignors Hip Color & No

Index to Consignors Hip Color & No. Sex Name,Year Foaled Sire Dam Barn 37 Consigned by Allied Bloodstock, Agent I Broodmare 880 b. m. Provobay, 2000 Dynaformer Del Sovereign Barn 37 Consigned by Allied Bloodstock, Agent II Broodmare prospect 1053 b. m. Cuff Me, 2007 Officer She'sgotgoldfever Barn 37 Consigned by Allied Bloodstock, Agent III Yearling 1164 ch. c. unnamed, 2011 First Samurai Jill's Gem Barn 37 Consigned by Allied Bloodstock, Agent IV Racing or broodmare prospect 1022 dk. b./br. f. Blue Catch, 2008 Flatter Nabbed Barn 37 Consigned by Allied Bloodstock, Agent V Yearling 978 dk. b./br. c. unnamed, 2011 Old Fashioned With Hollandaise Barn 37 Consigned by Allied Bloodstock, Agent VI Yearling 992 dk. b./br. c. First Defender, 2011 First Defence Altos de Chavon Barn 37 Consigned by Allied Bloodstock, Agent VII Broodmare 890 gr/ro. m. Refrain, 1999 Unbridled's Song Inlaw Barn 37 Consigned by Allied Bloodstock, Agent for Don Ameche III and Hayden Noriega Yearling 1014 ch. c. unnamed, 2011 Any Given Saturday Babeinthewoods Barn 37 Consigned by Allied Bloodstock, Agent for Don Ameche III, Don Ameche Jr. and Prancing Horse Enterprise Yearling 1124 dk. b./br. c. unnamed, 2011 Harlan's Holiday Grandstone Barn 29 Consigned by Baccari Bloodstock LLC, Agent Racing or broodmare prospects 897 b. m. Rock Hard Baby, 2007 Rock Hard Ten Bully's Del Mar 916 b. f. Shesa Calendargirl, 2009 Pomeroy Memory Rock Barn 38 Consigned by Blackburn Farm (Michael T. Barnett), Agent Broodmares 873 b. m. Prado's Treasure, 2006 Yonaguska Madrid Lady 961 ch. -

Northern Dancer (Derby)

LES DERBIES EUROPEENS DE NORTHERN DANCER DERBY STAKES Année Vainqueur Père Ascendants Paternels Père de Mère 1970 Nijinsky Northern Dancer Bull Page 1977 The Minstrel Northern Dancer Victoria Park 1982 Golden Fleece Nijinsky Northern Dancer Vaguely Noble 1984 Secreto Northern Dancer Secretariat 1986 Shahrastani Nijinsky Northern Dancer Thatch 1988 Kahyasi Ile de Bourbon Nijinsky Northern Dancer Blushing Groom 1991 Generous Caerleon Nijinsky Northern Dancer Master Derby 1993 Commander in Chief Dancing Brave Lyphard Northern Dancer Roberto 1994 Erhaab Chief's Crown Danzig Northern Dancer Riverman 1995 Lammtarra Nijinsky Northern Dancer Blushing Groom 1999 Oath Fairy King Northern Dancer Troy 2000 Sinndar Grand Lodge Chief's Crown Danzig Lashkari 2001 Galileo Sadler's Wells Northern Dancer Miswaki 2002 High Chaparral Sadler's Wells Northern Dancer Darshaan 2004 North Light Danehill Danzig Northern Dancer Rainbow Quest 2005 Motivator Montjeu Sadler's Wells Northern Dancer Gone West 2007 Authorized Montjeu Sadler's Wells Northern Dancer Saumarez 2008 New Approach Galileo Sadler's Wells Northern Dancer Ahonoora 2009 Sea The Stars Cape Cross Green Desert Danzig Miswaki 2011 Pour Moi Montjeu Sadler's Wells Northern Dancer Darshaan IRISH DERBY Année Vainqueur Père Ascendants Paternels Père de Mère 1970 Nijinsky Northern Dancer Bull Page 1977 The Minstrel Northern Dancer Victoria Park 1982 Assert Be My Guest Northern Dancer Sea Bird 1983 Shareef Dancer Northern Dancer Sir Ivor 1984 El Gran Senor Northern Dancer Buckpasser 1986 Shahrastani Nijinsky -

Comparison of the Performance and Precocity of Winners of the Most Important European Classic Races

Original Paper Czech J. Anim. Sci., 49, 2004 (2): 86–92 Czech J. Anim. Sci., 49, 2004 (2): 86–92 Original Paper Comparison of the performance and precocity of winners of the most important European classic races I. J�������, D. M����, S. S�������� Faculty of Agronomy, Mendel University of Agriculture and Forestry, Brno, Czech Republic ABSTRACT: Racing performance of winners of European classic races and of two-year-old horses was compared on the basis of two classic races: 1 600–1 609 m (one mile) and 2 100–2 414 m (Derby). The horses included in our comparisons were winners of classic races held in England, France and Ireland in 1993–2002. The performance of the winners of classic races was based on the international classification of the performance of three-year-old horses (Classifications internationales) in kg and lb (rating) and used as the characteristics of performance. Comparisons of the correlations between the performance of winners of the most important classic races and their performance rating as two-year-olds were based on the results of 126 winners of 13 classic races. We calculated Pearson’s correla- tion. The correlation coefficients of all the groups concerned were low (r = 0.109–0.325). The correlation coefficient of racing performances was significant (P < 0.05) only in the classic mile mare race. Keywords: horses; English Thoroughbred; racing performance; classic races One of the basic characteristics of the English right is respected, however it cannot completely Thoroughbred is precocity (Misař et al., 2000). eliminate the differences in the physical and psy- Due to this property the English Thoroughbred chic maturity of the youngest horses.