A Conversation Analytic Approach to the Study Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alignment in Syntax: Quotative Inversion in English

Alignment in Syntax: Quotative Inversion in English Benjamin Bruening, University of Delaware rough draft, February 5, 2014; comments welcome Abstract This paper explores the idea that many languages have a phonological Align(ment) constraint that re- quires alignment between the tensed verb and C. This Align constraint is what is behind verb-second and many types of inversion phenomena generally. Numerous facts about English subject-auxiliary inversion and French stylistic inversion fall out from the way this Align constraint is stated in each language. The paper arrives at the Align constraint by way of a detailed re-examination of English quotative inversion. The syntactic literature has overwhelmingly accepted Collins and Branigan’s (1997) conclusion that the subject in quotative inversion is low, within the VP. This paper re-examines the properties of quotative inversion and shows that Collins and Branigan’s analysis is incorrect: quotative inversion subjects are high, in Spec-TP, and what moves is a full phrase, not just the verb. The constraints on quotative inver- sion, including the famous transitivity constraint, fall out from two independently necessary constraints: (1) a constraint on what can be stranded by phrasal movement like VP fronting, and (2) the aforemen- tioned Align constraint which requires alignment between V and C. This constraint can then be seen to derive numerous seemingly unrelated facts in a single language, as well as across languages. Keywords: Generalized Alignment, quotative inversion, subject-in-situ generalization, transitivity restric- tions, subject-auxiliary inversion, stylistic inversion, verb second, phrasal movement 1 Introduction This paper explores the idea that the grammar of many languages includes a phonological Align(ment) con- straint that requires alignment between the tensed verb and C. -

The Morphosyntax of Jejuan – Ko Clause Linkages

The Morphosyntax of Jejuan –ko Clause Linkages † Soung-U Kim SOAS University of London ABSTRACT While clause linkage is a relatively understudied area within Koreanic linguistics, the Korean –ko clause linkage has been studied more extensively. Authors have deemed it interesting since depending on the successive/non-successive interpretation of its events, a –ko clause linkage exhibits all or no properties of what is traditionally known as coordination or subordination. Jejuan –ko clauses may look fairly similar to Korean on the surface, and exhibit a similar lack of semantic specification. This study shows that the traditional, dichotomous coordination-subordination opposition is not applicable to Jejuan –ko clauses. I propose that instead of applying a-priori categories to the exploration of clause linkage in Koreanic varieties, one should apply a multidimensional model that lets patterns emerge in an inductive way. Keywords: clause linkage, –ko converb, Jejuan, Jejueo, Ceycwu dialect 1. Introduction Koreanic language varieties are well-known for their richness in manifestations of clause linkage, much of which is realised by means of specialised verb forms. Connecting to an ever-growing body of research in functional-typological studies (cf. Haspelmath and König 1995), a number of authors in Koreanic linguistics have adopted the term converb for these forms (Jendraschek and Shin 2011, 2018; Kwon et al. 2006 among others). Languages such as Jejuan (Song S-J 2011) or Korean (Sohn H-M 2009) make extensive use of an unusually high number of converbs, connecting clauses within a larger sentence structure which may correspond to * This work was supported by the Laboratory Programme for Korean Studies through the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and Korean Studies Promotion Service of the Academy of Korean Studies (AKS-2016-LAB-2250003), the Endangered Languages Documentation Programme of the Arcadia Fund (IGS0208), as well as the British Arts and Humanities Research Council. -

Language Documentation and Description

Language Documentation and Description ISSN 1740-6234 ___________________________________________ This article appears in: Language Documentation and Description, vol 10: Special Issue on Humanities of the lesser-known: New directions in the description, documentation and typology of endangered languages and musics. Editors: Niclas Burenhult, Arthur Holmer, Anastasia Karlsson, Håkan Lundström & Jan-Olof Svantesson The Wichita pitch phoneme: a first look DAVID S. ROOD Cite this article: David S. Rood (2012). The Wichita pitch phoneme: a first look. In Niclas Burenhult, Arthur Holmer, Anastasia Karlsson, Håkan Lundström & Jan-Olof Svantesson (eds) Language Documentation and Description, vol 10: Special Issue on Humanities of the lesser-known: New directions in the description, documentation and typology of endangered languages and musics. London: SOAS. pp. 113-131 Link to this article: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/116 This electronic version first published: July 2014 __________________________________________________ This article is published under a Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC (Attribution-NonCommercial). The licence permits users to use, reproduce, disseminate or display the article provided that the author is attributed as the original creator and that the reuse is restricted to non-commercial purposes i.e. research or educational use. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ______________________________________________________ EL Publishing For more EL Publishing articles and services: Website: http://www.elpublishing.org Terms of use: http://www.elpublishing.org/terms Submissions: http://www.elpublishing.org/submissions The Wichita pitch phoneme: a first look David S. Rood 1. Introduction Wichita is a polysynthetic language currently spoken fluently by only one person, Doris Jean Lamar, who is in her mid-80s and lives in Anadarko, Oklahoma, USA. -

Word Order, Parameters and the Extended COMP

Alice Davison, University of Iowa [email protected] January 2006 Word order, parameters, and the Extended COMP projection Abstract The structure of finite CP shows some unexpected syntactic variation in the marking of finite subordinate clauses in the Indic languages, which otherwise are strongly head-final.. Languages with relative pronouns also have initial complementizers and conjunctions. Languages with final yes/no question markers allow final complementizers, either demonstratives or quotative participles. These properties define three classes, one with only final CP heads (Sinhala), one with only initial CP heads (Hindi, Panjabi, Kashmiri) and others with both possibilities. The lexical differences of final vs initial CP heads argue for expanding the CP projection into a number of specialized projections, whose heads are all final (Sinhala), all initial, or mixed. These projections explain the systematic variation in finite CPs in the Indic languages, with the exception of some additional restrictions and anomalies in the Eastern group. 1. Introduction In this paper, I examine two topics in the syntactic structure of clauses in the Indic languages. The first topic has to do with the embedding of finite clauses and especially about how embedded finite clauses are morphologically marked. The second topic focuses on patterns of linear order in languages, parameters of directionality in head position. The two topics intersect in the position of these markers of finite subordinate clauses in the Indic languages. These markers can be prefixes or suffixes, and I will propose that they are heads of functional projections, just as COMP is traditionally regarded as head of CP. The Indic languages are all fundamentally head-final languages; the lexically heads P, Adj, V and N are head-final in the surface structure, while only the functional head D is not. -

1. 叉燒包BBQ Pork Bun 2. 火腿蛋包ham & Egg Bun 3. 豆沙包bean Paste Bun 4. 豆沙菠罗包bean Paste W

BUNS 1. 叉燒包 BBQ Pork Bun 2. 火腿蛋包 Ham & Egg Bun 3. 豆沙包 Bean Paste Bun 4. 豆沙菠罗包 Bean Paste w/ Sweet Top Bun 5. 奶王包 Egg Custard Bun 6. 奶王菠罗包 Egg Custard w/ Sweet Top Bun 7. 火腿蔥包 Ham & Green Onion Bun 8. 咖喱牛肉包 Curry Beef Bun 9. 雞包 Chicken Bun 10. 火腿芝士包 Ham & Cheese Bun 11. 腊腸包 Chinese Sausage Bun 12. 腸仔包 Hot Dog Bun 13. 雞尾菠罗包 Coconut Sweet Top Bun 14. 肉松包 Pork Sung Bun 15. 芋頭包 Taro Bun 16. 丹麥包 Raisin Stick Bread 17. 紙包蛋糕 Sponge Cake 18. 椰絲包 Coconut Bun 19. 椰絲卷 Coconut Twist Bun 20. 菠蘿包 Pineapple Sweet Top Bun 21. 牛油包 Butter Bun 22. 奶油包 Cream Bun 23. 雞尾包 Coconut Cocktail Bun 24. 墨西哥 Butter Top Bun 25. 叉燒菠蘿包 BBQ Pork w/ Sweet Top Bun 26. 餐包 Plain Dinner Rolls 27. 提子餐包 Raisin Dinner Roll 28. 粟米火腿蔥包 Ham & Corn Bun 1. 燒賣 Pork Dumplings 2. 蝦餃 Shrimp Dumplings 3. 蝦米腸 Steamed Noodles w/ Shrimp & Green Onions 4. 牛腸 Steamed Rice Crepe w/ Beef 5. 蝦腸 Steamed Rice Crepe w/ Shrimp 6. 淨腸 Plain Steamed Crepe 7. 蘿葡糕 Turnip Cake 8. 芋頭糕 Taro Cake 9. 白雲鳳爪 Marinated Chicken Feet (Cold) 10. 酸辣鳳爪 Spicy Chicken Feet (Cold) 11. 鳳爪 Chicken Feet 12. 鮮竹卷 Bean Curd Roll w/ Pork 13. 糯米卷 Sticky Rice Roll 14. 咸水角 Pork & Shrimp Turnover 15. 糯米雞 Sticky Rice in Lotus Leaf with Chicken, Chinese Sausage, and Egg PASTRIES 1. 葡撻 Portuguese-Style Milk Egg Tart 2. 蛋撻 Egg Custard Tart 3. 煎堆 Sesame Ball w/ Bean Paste 4. 豆沙糯米糍 Bean Paste Rice Cake 5. -

SYSU 29 MAR 2019 OBR CHINA IMAGINED Reduced

Gregory B. Lee Professor of Chinese and Transcultural Studies University of Lyon Director, Institut d’études transtextuelles et transculturelles How far back? Four to seven thousand years or more? To the unification under short-lived Qin dynasty in 221 BCE To the European use of the name “China” in the 16th century? To the 1912 “Republic of China” when the “Chinese” administration first employed the term “China” Where does the word China come from? In 1516, a Portuguese named Duarte Barbosa employed the word “China” Later in several European languages: Cina in Italy, Chine in France, and in English as China. Jeff Wade has demonstrated that ʐina designated a state in the south of what is now known as China, a territory inhabited by the Lolo or Yi peoples But no polity or society ever used the name “China or any variants of such” For several centuries Europeans used the word China, alongside such terms as Tartary, Cathay or the Celestial Empire, to describe, narrate and map the territory governed by the Ming rulers and later by the Manchus . / 1842829 Treaty of Nanjing (Nanking), 1842 HER MAJESTY the Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and His Majesty the Emperor of China [] , being desirous of putting an end to the misunderstandings and consequent hostilities which have arisen between the two countries, have resolved to conclude a Treaty for that purpose, and have therefore named as their Plenipotentiaries, that is to say: Her Majesty the Queen of Great Britain and Ireland, HENRY POTTINGER, Bart., -

Food Names Section I

Food Names Section I. Dialogues Section I. Dialogues 2 Unit 1 General Dialogues 2 Unit 2 At specific kinds of restaurants 14 Unit 1 General Dialogues Unit 3 Specific situations 19 Unit 4 Buying food at a wet market 22 1.1 Choose a restaurant Section II. Food 25 Unit 1 Meat 25 (a) Asking your friend where to go Unit 2 Seafood 29 1) What do you want to eat? Unit 3 Vegetables 31 néih séung sihk mâtmât----yéhyéh a? 你你你你你你你你你你呀呀呀??? Unit 4 Fruit 35 Unit 5 Staple food and eggs 37 2) How about Japanese food ? Section III. Expressions 39 (sihk) YahtYaht----búnbún yéh hóuhóu----¬h¬h¬h¬h----hóuhóu a? (((你你你)))日日日日日日好好好好好好好好呀呀呀呀??? Unit 1 Dialogue Expressions 39 (“ 日本菜 Yaht-bún-choi” means “Japanese cuisine” which sounds more formal) Unit 2 Notes on menus 40 3) How about having dim sum? Unit 3 Modification for dish names 42 heui yyáááámmmm----chchchchààààhh hh hóh óóóuuuu----¬¬¬¬hhhh----hhhhóóóóuu a? 去去去去去去去去好好好好好好好好呀呀呀呀? (more common) /// Unit 4 Restaurants 44 sihk ddíííímmmm----ssssûûûûmm hm hóh óóóuuuu----¬¬¬¬hhhh----hhhhóóóóuu a? 你你你食你食食食食食好好好好好好好好呀呀呀呀? (? (less( less common but Section IV. Dish names 46 Unit 1 Dim Sum 46 clearer) Unit 2 Chinese restaurant 50 4) How about going to a Chinese restaurant Unit 3 Hong Kong style café 54 去去去去去去去去好好好好好好好好呀呀呀呀 Unit 4 Barbecued meat shop 60 heui jjááááuuuu----llllààààuhuh hhóóóóuuuu----¬¬¬¬hhhh----hhhhóóóóuu a? ??? Unit 5 Noodle shop 61 5) Anything is fine / I don’t mind. Unit 6 Congee shop 64 sih daahn â 是是是是是是 / móuh só waih 冇冇冇冇冇冇冇冇 Unit 7 Dessert shop 66 Unit 8 Western restaurant 67 6) It’s fine Unit 9 Asian restaurant 68 hóu â ! 好好好!!! / hóu aak! 好好好好好好!!! Unit 10 Household Food 68 7) Which Chinese restaurant taste good? Section V. -

Taro Savory Cake,Taiwanese Turnip Cake

Taro Savory Cake This is a very typical Chinese dish found in dim sum…super easy and it makes a great side dish, loaded with lots of flavors. I got a big package of fresh peeled taro root when at the local Asian store and after many debate (between myself) decided to make two dishes with it…one is this savory cake and the next will be on my next week post…so be patience as you will see two recipes using taro… This recipe is not very different from the Taiwanese Turnip Cake…I mainly added taro instead of turnip and much less rice flour, so the taro would be the star of this dish. – What is taro root? Taro root is very popular in Asian cuisine, it is like potato, starchy but with a sweet and nutty note in its flavor. Taro grows in tropical and sub-tropical climate, therefore a staple food in countries with such a climate. Taro has purple speckles all over its flesh and it can be fried, boiled, roasted, simmered, mashed…made into savory or sweet dish. – Have you ever had this savory taro cake? If you had not tried this dish, I urge you to try next time when visiting a dim sum restaurant. It is commonly found in dim sum cart, but I must admit that this might not be one of the popular dishes if you are not familiar with it…they usually fry right there before serving… – How you serve this savory cake? It is usually served with a side of hot sauce. -

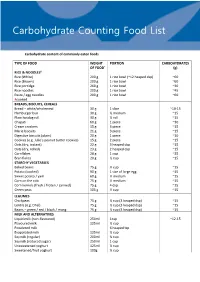

Carbohydrate Counting List

Tr45 Carbohydrate Counting Food List Carbohydrate content of commonly eaten foods TYPE OF FOOD WEIGHT PORTION CARBOHYDRATES OF FOOD* (g) RICE & NOODLES# Rice (White) 200 g 1 rice bowl (~12 heaped dsp) ~60 Rice (Brown) 200 g 1 rice bowl ~60 Rice porridge 260 g 1 rice bowl ~30 Rice noodles 200 g 1 rice bowl ~45 Pasta / egg noodles 200 g 1 rice bowl ~60 #cooked BREADS, BISCUITS, CEREALS Bread – white/wholemeal 30 g 1 slice ~10-15 Hamburger bun 30 g ½ medium ~15 Plain hotdog roll 30 g ½ roll ~15 Chapati 60 g 1 piece ~30 Cream crackers 15 g 3 piece ~15 Marie biscuits 21 g 3 piece ~15 Digestive biscuits (plain) 20 g 1 piece ~10 Cookies (e.g. Julie’s peanut butter cookies) 15 g 2 piece ~15 Oats (dry, instant) 22 g 3 heaped dsp ~15 Oats (dry, rolled) 23 g 2 heaped dsp ~15 Cornflakes 28 g 1 cup ~25 Bran flakes 20 g ½ cup ~15 STARCHY VEGETABLES Baked beans 75 g ⅓ cup ~15 Potato (cooked) 90 g 1 size of large egg ~15 Sweet potato / yam 60 g ½ medium ~15 Corn on the cob 75 g ½ medium ~15 Corn kernels (fresh / frozen / canned) 75 g 4 dsp ~15 Green peas 105 g ½ cup ~15 LEGUMES Chickpeas 75 g ½ cup (3 heaped dsp) ~15 Lentils (e.g. Dhal) 75 g ½ cup (3 heaped dsp) ~15 Beans – green / red / black / mung 75 g ½ cup (3 heaped dsp) ~15 MILK AND ALTERNATIVES Liquid milk (non-flavoured) 250ml 1cup ~12-15 Flavoured milk 125ml ½ cup Powdered milk 6 heaped tsp Evaporated milk 125ml ½ cup Soymilk (regular) 200ml ¾ cup Soymilk (reduced sugar) 250ml 1 cup Unsweetened yoghurt 125ml ½ cup Sweetened/fruit yoghurt 100g ⅓ cup TYPE OF FOOD WEIGHT PORTION CARBOHYDRATES OF -

The Sociolinguistics of a Short-Lived Innovation: Tracing the Development of Quotative All Across Spoken and Internet Newsgroup Data

Language Variation and Change, 22 (2010), 191–219. © Cambridge University Press, 2010 0954-3945/10 $16.00 doi:10.1017/S0954394510000098 The sociolinguistics of a short-lived innovation: Tracing the development of quotative all across spoken and internet newsgroup data I SABELLE B UCHSTALLER Newcastle University J OHN R. RICKFORD,ELIZABETH C LOSS T RAUGOTT,THOMAS W ASOW AND A RNOLD Z WICKY Stanford University ABSTRACT This paper examines a short-lived innovation, quotative all, in real and apparent time. We used a two-pronged method to trace the trajectory of all over the past two decades: (i) Quantitative analyses of the quotative system of young Californians from different decades; this reveals a startling crossover pattern: in 1990/1994, all predominates, but by 2005, it has given way to like. (ii) Searches of Internet newsgroups; these confirm that after rising briskly in the 1990s, all is declining. Tracing the changing usage of quotative options provides year-to-year evidence that all has recently given way to like. Our paper has two aims: We provide insights from ongoing language change regarding short-term innovations in the history of English. We also discuss our collaboration with Google Inc. and argue for the value of newsgroups to research projects investigating linguistic variation and change in real time, especially where recorded conversational tokens are relatively sparse. An earlier version of this paper was presented at NWAV 35 (New Ways of Analyzing Variation) at Ohio State University in Columbus. We are grateful for comments from the audience, in particular to John V. Singler and Mary Bucholtz. -

The Quotative Complementizer Says “I'm Too Baroque for That” 1 Introduction

The Quotative Complementizer Says “I’m too Baroque for that” Rahul Balusu,1 EFL-U, Hyderabad Abstract We build a composite picture of the quotative complementizer (QC) in Dravidian by examining its role in various left-peripheral phenomena – agreement shift, embedded questions; and its par- ticular manifestation in various constructions like noun complement clauses, manner adverbials, rationale clauses, with naming verbs, small clauses, and non-finite embedding, among others. The QC we conclude is instantiated at the very edge of the clause it subordinates, outside the usual left periphery, comes with its own entourage of projections, and is the light verb say which does not extend its projection. It adjoins to the matrix spine at various heights (at the vP level it gets a θ-role, and thus argument properties) when it does extend its projection, and like a verb selects clauses of various sizes (CP, TP, small clause). We take the Telugu QC ani as illustrative, being more transparent in form to function mapping, but draw from the the QC properties of Malayalam, Kannada, Bangla, and Meiteilon too. 1 Introduction Complementizers –conjunctions that play the role of identifying clauses as complements –are known to have quite varied lexical sources (Bayer 1999). In this paper we examine in detail the polyfunctional quotative complementizer (QC) in Dravidian languages by looking at its particular manifestation in various construc- tions like noun complement clauses, manner adverbials, rationale clauses, naming/designation clauses, small clauses, non-finite embedding. We also look to two left-peripheral phenomena for explicating the syntax and semantics of the QC –Quasi Subordination, and Monstrous Agreement. -

Unity and Diversity in Grammaticalization Scenarios

Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios Edited by Walter Bisang Andrej Malchukov language Studies in Diversity Linguistics 16 science press Studies in Diversity Linguistics Chief Editor: Martin Haspelmath In this series: 1. Handschuh, Corinna. A typology of marked-S languages. 2. Rießler, Michael. Adjective attribution. 3. Klamer, Marian (ed.). The Alor-Pantar languages: History and typology. 4. Berghäll, Liisa. A grammar of Mauwake (Papua New Guinea). 5. Wilbur, Joshua. A grammar of Pite Saami. 6. Dahl, Östen. Grammaticalization in the North: Noun phrase morphosyntax in Scandinavian vernaculars. 7. Schackow, Diana. A grammar of Yakkha. 8. Liljegren, Henrik. A grammar of Palula. 9. Shimelman, Aviva. A grammar of Yauyos Quechua. 10. Rudin, Catherine & Bryan James Gordon (eds.). Advances in the study of Siouan languages and linguistics. 11. Kluge, Angela. A grammar of Papuan Malay. 12. Kieviet, Paulus. A grammar of Rapa Nui. 13. Michaud, Alexis. Tone in Yongning Na: Lexical tones and morphotonology. 14. Enfield, N. J (ed.). Dependencies in language: On the causal ontology of linguistic systems. 15. Gutman, Ariel. Attributive constructions in North-Eastern Neo-Aramaic. 16. Bisang, Walter & Andrej Malchukov (eds.). Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios. ISSN: 2363-5568 Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios Edited by Walter Bisang Andrej Malchukov language science press Walter Bisang & Andrej Malchukov (eds.). 2017. Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios (Studies in Diversity Linguistics