Divine and Diabolic Radio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Türk Halı, Kilini Ve Kınlılarında Kullanılan

Türk Halı, Kilini ve kınlılarında Kullanılan Resim/Picture I Kökboya {Rubia tincrorum L.) Madder ( Rubia tincrorum L.) Yrd. Doç. Dr. Recep Türk dokumalarında tabiattan elde edilen boyar- sülfat), siyah renkler için ise Fe2 (S04)3 (demir 3 sülfat), maddelerin kullanıldığı bilinmektedir. Halk arasında FeS04 (demir 2 sülfat) ve kalay tuzlandır. Mordan olarak yaygın bir kanı ve adlandırma olarak bu türlerin hepsi Sn2+ katyonu 16-17, yüzyıllarda Avrupa’da kullanılmış “kökboya” biçiminde anılmaktadır. Bu makalede olmasına rağmen Türk ve İran tekstillerinde görüldüğü üzere boyalar sadece bitki köklerinden değil, kullanılmamıştır.5 bitkilerin toprak üstünde kalan bölümlerinden ve hatta böceklerden de elde edilmektedir. * Marmara Üniversitesi, Güzel Sanatlar Fakültesi, Doğal Boya Araştırma Lâboratuvarı, Öğretim Üyesi. 1. H. Böhmer- R. Karadağ, “Analysis of Dyes”, Kaitag, 1. GİRİŞ Textile A rt From Daghestan, Textile Art Publication, London Türk halı, kilim ve kumaşlarında doğal boyarmaddeler 1993, s. 43; T. Eşberk- M. Harmancıoğlu, “Bazı Bitki Boyalannın ve boyama kaynakları sınırlı sayıda kullanılmıştır. Çoğu Haslık Dereceleri”, Ankara Üniversitesi Ziraat Fakültesi Yıllığı, litaretürlerin aksine boyama kaynağı olarak verilen Yıl 2, Fasikül 4,1952, s. 326; H. Schweppe, “Idenification of Dyes bitkilerin çoğunun çeşitli haslıklarının düşük olması ve in Historic Textile Materials”, Historic Textil And Paper I Materials: Convertion and Characterization, American Society, bazılarının ise boyarmadde içermediği yapılmış olan Washington D.С. 1986, s. 164; H. Schweppe, Handbuch der çalışmalarda tespit edilmiştir.1 Tarihî tekstillerin (halı, Naturfairbstoffe, Landsberg 1992; H. Schweppe, Historic Textile kilim ve çeşitli kumaşlarda) yapılmış olan boyarmadde and Paper Materials I, American Society, Washington, D.С. 1986, analizleri sonucunda, kullanılmış olan boyarmaddeler ve s. 174-183; H. Schweppe, Historic Textile and Paper Materials II, boyarmadde kaynaklarının sınırlı sayıda olduğu tespit American Society, Washington, D.C. -

Report on Future Funding of Public Service Broadcasting

Tithe an Oireachtais An Comhchoiste um Chumarsáid, Gníomhú ar son na hAeráide agus Comhshaol Tuarascáil ón gComhchoiste maidir leis Craoltóireacht Seirbhíse Poiblí a Mhaoiniú sa Todhchaí A leagadh faoi bhráid dhá Theach an Oireachtais 28 Samhain 2017 Houses of the Oireachtas Joint Committee on Communications, Climate Action and Environment Report of the Joint Committee on the Future Funding of Public Service Broadcasting Laid before both Houses of the Oireachtas 28 November 2017 32CCAE002 Tithe an Oireachtais An Comhchoiste um Chumarsáid, Gníomhú ar son na hAeráide agus Comhshaol Tuarascáil ón gComhchoiste maidir leis Craoltóireacht Seirbhíse Poiblí a Mhaoiniú sa Todhchaí A leagadh faoi bhráid dhá Theach an Oireachtais 28 Samhain 2017 Houses of the Oireachtas Joint Committee on Communications, Climate Action and Environment Report of the Joint Committee on the Future Funding of Public Service Broadcasting Laid before both Houses of the Oireachtas 28 November 2017 32CCAE002 Report on Future Funding of Public Service Broadcasting TABLE OF CONTENTS Brollach .............................................................................................................. 3 Preface ............................................................................................................... 4 1. Key Issue: The Funding Model – Short Term Solutions .......................... 6 Recommendation 1 - Fairness and Equity ............................................................ 6 Recommendation 2 – All Media Consumed ........................................................... -

Shortwave-Listener's

skï.. Radio lhaek TWO DOLLARS AND TWENTY—FIVE CENTS 62-2032 Shortwave Listener's Guide by H. Charles Woodruff Howard W. Sams & Co., Inc. 4300 WEST 62ND ST. INDIANAPOLIS, INDIANA 46268 USA Copyright 0 1964, 1966, 1968, 1970, 1973, 1976, and 1980 by Howard W. Sams & Co., Inc. Indianapolis, Indiana 46268 EIGHTH EDITION FIRST PRINTING-1980 All rights reserved. No part of this book shall be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher. No patent liability is assumed with respect to the use of the information contained herein. While every pre- caution has been taken in the preparation of this book, the publisher assumes no responsibility for errors or omissions. Neither is any liability assumed for damages resulting from the use of the information contained herein. International Standard Book Number: 0-672-21655-8 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 79-67132 Printed in the United States of America. Preface Every owner of a shortwave receiving set is familiar with the thrill that comes from hearing a distant station broadcasting from a foreign country. To hundreds of thousands of people the world over, short- wave listening (often referred to as swl) represents the most satisfy- ing, the most worthwhile of all hobbies. It has been estimated that more than 25 million shortwave receivers are in the hands of the American public, with the number increasing daily. To explore the international shortwave broadcasting bands in a knowledgeable manner, the shortwave listener must have available a list of shortwave stations, their frequencies, and their times of trans- mission. -

CV – June 2021 – 1

SÉVERINE AUTESSERRE * Department of Political Science. 3009 Broadway. New York, NY 10027-6598 ( (1) (212) 854-4877 : [email protected] / http://www.severineautesserre.com CURRENT POSITION: Professor, Department of Political Science, Barnard College, Columbia University, July 2007 - Present Assistant Professor from 2007 to 2015; promoted to Associate Professor with tenure in 2015 and to Professor in 2017; elected Department Chair (2022 - 2025) Research civil and international wars, international interventions, and African politics, and disseminate research findings through seminars, conferences, and scientific articles Main field research site: Democratic Republic of Congo. Other sites: Burundi, Cyprus, Colombia, Israel-Palestine, Northern Ireland, South Sudan, Timor-Leste, Somaliland Teach undergraduate and graduate classes on international relations and African politics Hold a courtesy appointment (since 2009) and a senior research scholar position (since 2015) at the School of International and Public Affairs Affiliated with the Columbia University Saltzman Institute for War and Peace Studies, Columbia University Institute for African Studies, Columbia University Institute for the Study of Human Rights, and Barnard College Africana Studies Program PUBLICATIONS Books The Frontlines of Peace: An Insider’s Guide to Changing the World. • Hardback & eBook: Oxford University Press, 2021 Audiobook: Audible, 2021 • Reviewed to date in: Diplomatie, The Financial Times, Foreign Affairs, International Peacekeeping, Política Exterior, The Economist, -

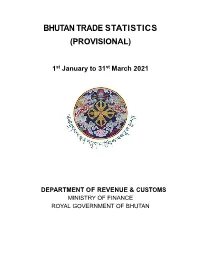

Bhutan Trade Statistic 2021 1St Quarter

BHUTAN TRADE STATISTICS (PROVISIONAL) 1st January to 31st March 2021 DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE & CUSTOMS MINISTRY OF FINANCE ROYAL GOVERNMENT OF BHUTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTENTS PAGE NO. 1. Balance of Trade 1.1. Overall Balance of Trade I 1.2. Balance of Trade with India I 1.3. Balance of Trade with Countries other than India I 2. Trade in Electricity I 3. Top Ten Import and Export 3.1 Top Ten Commodities Import II 3.2 Top Ten Commodities Export II 4. Region wise Import and Export III 5. Country wise Import Ranking IV 6. Country wise Export Ranking Order V 7. Abbreviation VI 8. Contact details of BTS focal person VI 9. Appendix :- Appendix I: Import by BTC Section 1-1 Appendix II: Import by BTC Chapter 2-6 Appendix III: Import by BTC Code 7-142 Appendix IV: Export by BTC Section 143-143 Appendix V: Export by BTC Chapter 144-146 Appendix VI: Export by BTC Code 147-164 Appendix VII: Import from Countries other than India by Country and Commodity 165-278 Appendix VIII: Export to Countries other than India by Country and Commodity 279-288 Appendix IX: Export to Countries other than India by Commodity and Country 289-294 1. Balance of Trade 1.1 Overall Balance of Trade Trade Trade excluding Electricity Trade including Electricity Export 19,378.18 19,509.45 Import 8,029.42 9,326.05 Balance (11,348.76) (10,183.40) 1.2 Balance of Trade with India Trade Trade excluding Electricity Trade including Electricity Export 16,563.77 16,695.05 Import 5,410.84 6,707.48 Balance (11,152.93) (9,987.57) 1.3 Balance of the Trade with Countries other than India Trade Trade excluding Electricity Trade including Electricity Export 2,814.41 2,814.41 Import 2,618.58 2,618.58 Balance (195.83) (195.83) 2. -

Redalyc.Rural School in the Tenza Valley, Rural Education and Agroecology Reflections on Rural "Development"

Agronomía Colombiana ISSN: 0120-9965 [email protected] Universidad Nacional de Colombia Colombia Fernando Mejía, Miguel Rural school in the Tenza Valley, rural education and agroecology reflections on rural "development" Agronomía Colombiana, vol. 29, núm. 2, mayo-agosto, 2011, pp. 309-314 Universidad Nacional de Colombia Bogotá, Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=180322766017 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Rural school in the Tenza Valley, rural education and agroecology reflections on rural “development” Escuela campesina del Valle de Tenza educación rural y agroecología reflexiones sobre el “desarrollo” rural Miguel Fernando Mejía1 ABSTRACT RESUMEN The municipality of Sutatenza (Boyaca), constitutes an impor- El municipio de Sutatenza (Boyacá) constituye un referente tant reference for rural education in Colombia due to “Radio importante para la educación rural campesina en Colombia Sutatenza”(Educational Radio) and the People’s Cultural Action puesto que allí tuvo lugar la experiencia de las escuelas ra- in the mid-twentieth century. Currently, in the same town, a diofónicas ó “Radio Sutatenza” y la Acción Cultural Popular a process called the Campesina Community School del Valle de mediados del Siglo XX. Actualmente en el mismo municipio Tenza has been brewing, under an agroecological approach, se viene gestando un proceso comunitario denominado la guided in its work to the cultural and productive Andean Escuela Campesina del Valle de Tenza que, bajo un enfoque farmers, their families and their young people to cultivate in agroecológico, orienta su trabajo al acervo cultural y produc- them a return the field. -

La Herencia Científica Del Exilio Español En América

La herencia científica del exilio español en América. José Royo y Gómez en el Servicio Geológico Nacional de Colombia Carlos Alberto Acosta Rizo Prólogo Es indudable que existe un puente entre la ciencia colombiana y la europea tendido por los científicos de Europa que trabajaron en áreas diversas y, como no, en la historia natural, la minería, la geodesia, la paleontología y la geología. Los antecedentes se extienden a lo largo de los cinco siglos de historia compartida desde la misma llegada de Colón en 1492. Esta realidad histórica también es reciente (siglo XX) y debe ser abordada de modo que traspase la simple anécdota, y se interne en los asuntos valorativos de la contribución científica de los europeos en América, y de la aportación de América a éstos científicos, planteados como asuntos de significado social en su contexto local, y no sólo en un pretendido sentido universal, a pesar del asumido carácter periférico de los países involucrados. Uno de los principales representantes en Latinoamérica de la ‘ciencia española’ de la primera mitad del siglo XX, es el geólogo y paleontólogo José Royo Gómez (España 1895 -1939; Colombia, 1939 - 1951; Venezuela 1951 - 1961). Vi por primera vez su nombre en la placa que anuncia la entrada al Museo Geológico de Colombia (MGC) en las instalaciones del INGEOMINAS (Instituto Colombiano de Geología y Minería). Sin embargo, debo confesar que durante mi actividad profesional como geólogo en Colombia no tuve contacto con la labor de este personaje, pues las referencias a sus estudios están encubiertas por investigaciones más recientes. Fue en 2002 haciendo la investigación preliminar para el libro Intercambios Científicos entre España e Hispanoamérica, Ecos del siglo XX1, cuando cobré especial interés en él. -

1978-05-22 P MACHO MAN Village People RCA 7" Vinyl Single 103106 1978-05-22 P MORE LIKE in the MOVIES Dr

1978-05-22 P MACHO MAN Village People RCA 7" vinyl single 103106 1978-05-22 P MORE LIKE IN THE MOVIES Dr. Hook EMI 7" vinyl single CP 11706 1978-05-22 P COUNT ON ME Jefferson Starship RCA 7" vinyl single 103070 1978-05-22 P THE STRANGER Billy Joel CBS 7" vinyl single BA 222406 1978-05-22 P YANKEE DOODLE DANDY Paul Jabara AST 7" vinyl single NB 005 1978-05-22 P BABY HOLD ON Eddie Money CBS 7" vinyl single BA 222383 1978-05-22 P RIVERS OF BABYLON Boney M WEA 7" vinyl single 45-1872 1978-05-22 P WEREWOLVES OF LONDON Warren Zevon WEA 7" vinyl single E 45472 1978-05-22 P BAT OUT OF HELL Meat Loaf CBS 7" vinyl single ES 280 1978-05-22 P THIS TIME I'M IN IT FOR LOVE Player POL 7" vinyl single 6078 902 1978-05-22 P TWO DOORS DOWN Dolly Parton RCA 7" vinyl single 103100 1978-05-22 P MR. BLUE SKY Electric Light Orchestra (ELO) FES 7" vinyl single K 7039 1978-05-22 P HEY LORD, DON'T ASK ME QUESTIONS Graham Parker & the Rumour POL 7" vinyl single 6059 199 1978-05-22 P DUST IN THE WIND Kansas CBS 7" vinyl single ES 278 1978-05-22 P SORRY, I'M A LADY Baccara RCA 7" vinyl single 102991 1978-05-22 P WORDS ARE NOT ENOUGH Jon English POL 7" vinyl single 2079 121 1978-05-22 P I WAS ONLY JOKING Rod Stewart WEA 7" vinyl single WB 6865 1978-05-22 P MATCHSTALK MEN AND MATCHTALK CATS AND DOGS Brian and Michael AST 7" vinyl single AP 1961 1978-05-22 P IT'S SO EASY Linda Ronstadt WEA 7" vinyl single EF 90042 1978-05-22 P HERE AM I Bonnie Tyler RCA 7" vinyl single 1031126 1978-05-22 P IMAGINATION Marcia Hines POL 7" vinyl single MS 513 1978-05-29 P BBBBBBBBBBBBBOOGIE -

Conflictos Socioambientales En El Páramo De Guacheneque Y Estrategias De Conservación Para El Ordenamiento Ambiental Regional

CONFLICTOS SOCIOAMBIENTALES EN EL PÁRAMO DE GUACHENEQUE Y ESTRATEGIAS DE CONSERVACIÓN PARA EL ORDENAMIENTO AMBIENTAL REGIONAL ILDA MARCELA BERNAL CUESTA Universidad Nacional de Colombia Facultad de Artes, Maestría en Ordenamiento Urbano Regional Bogotá D.C. Colombia 2017 CONFLICTOS SOCIOAMBIENTALES EN EL PÁRAMO DE GUACHENEQUE Y ESTRATEGIAS DE CONSERVACIÓN PARA EL ORDENAMIENTO AMBIENTAL REGIONAL Ilda Marcela Bernal Cuesta Trabajo final presentado como requisito parcial para optar al título de: Magister en Ordenamiento Urbano Regional Directora: María Patricia Rincón Avellaneda Línea de Investigación: Dinámicas Urbano Regionales-Dinámicas Ambientales Universidad Nacional de Colombia Facultad de Artes Maestría en Ordenamiento Urbano Regional Bogotá D.C. Colombia 2017 A la vida, mi familia, y la naturaleza, porque ha sido esta triada la que le ha dado sentido a mi existencia. La majestuosidad de la naturaleza, y la diversidad de la misma han estado presentes desde mi infancia y han definido mi formación profesional. “Lo que fue este país, lo que es en el presente y lo que va a ser en el futuro, depende de la actitud que el hombre asuma frente a las montañas, porque lo demás es complemento” Ernesto Guhl Agradecimientos Quiero agradecer de manera especial a mi directora María Patricia Rincón Avellaneda, por sus aportes y observaciones puntuales en todo el proceso de elaboración y ajustes al trabajo final de maestría. Al señor Vidal González (guardabosque) y a los campesinos residentes en el páramo por sus saberes ancestrales y conocimiento del territorio. A mis compañeros, profesores, amigos y colegas por sus recomendaciones, sus puntos de vista, dudas e inquietudes. El mayor agradecimiento a mi familia que siempre ha estado apoyándome de forma incondicional en todas las etapas de mi vida. -

Ham Radio Magazine 1990

Filters. l'hc FL-:1'1,4 and FL-52A deliver razor sharp select ivi tv. 'A serious IIX'ers delight! 25clHz F1,.5:1,4 and FL-101 optional. The I(-71;; Gneral Coverage Receiver covers all bands. all mtdes and is backed by ICOM's full ontyar \varrantJSat any one THE HF FOR TODAYS ACnV€ AMATEUR. and AMTOR olxrations. ol our four North :!merican Senice Centers. Incsludt~s:*IRi~nd Stacking Rcgistcrs. *3!asirnum Operation Flexibility! The The IC-ili3 turns your dreams into reality! Each 1)andk \'F'O's rct;\in rhc l;isr sclecltd thrw step attenuator cuts multi-station frequc.nc!. nic~lcand filler ctioictl \vhtn overloads. *Built-in AC Supplv. Thr IC-765 changn t~ands.I'nducrs ti,? tpuivalml of is IN) jrrctlnt doty cycle r;~tdfor call 20 \.'I-0s; two Ixr hnntl. (;rrat lor niultiband olxration and sulwrh performance on all IIX'ing! $99 Full!. Tunable Memories. ni(des! *Fully :\utornatic .Antenna 0 Stort. i'requrncy. n~cxlc*:~nd filtrr st~ltu.tians. Tuner. With built-in C'I'[' and memory for IIacli one can Iw rrturncd and,or reprn extremely fast tuning and one-touch opera. ,q-anin~cdindrlxndrnt of VFO olxlra~ions. tion. \Vide tuning range. *C\Y Pitch FirstICOM in Communications .Lleniories 90-9:)also store split 'I'x. Kx frp Control. Total olxbrating comfort and I ! a I ' lli! I 11 ;.,,. bl L O,~l~,,~ii,.~WA 99110M convenience for successful contesti~~gand qucnc'ics. * IOZfz Readout. I'crfcct on-thr ~;;;~;~,~;~;~~!,~~;r~;~~,;;;~;;63 dot frt>qurncyselcrtion for nets. -

Textile Society of America Newsletter 28:1 — Spring 2016 Textile Society of America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Newsletters Textile Society of America Spring 2016 Textile Society of America Newsletter 28:1 — Spring 2016 Textile Society of America Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews Part of the Art and Design Commons Textile Society of America, "Textile Society of America Newsletter 28:1 — Spring 2016" (2016). Textile Society of America Newsletters. 73. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews/73 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Newsletters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME 28. NUMBER 1. SPRING, 2016 TSA Board Member and Newsletter Editor Wendy Weiss behind the scenes at the UCB Museum of Anthropology in Vancouver, durring the TSA Board meeting in March, 2016 Spring 2016 1 Newsletter Team BOARD OF DIRECTORS Roxane Shaughnessy Editor-in-Chief: Wendy Weiss (TSA Board Member/Director of External Relations) President Designer and Editor: Tali Weinberg (Executive Director) [email protected] Member News Editor: Caroline Charuk (Membership & Communications Coordinator) International Report: Dominique Cardon (International Advisor to the Board) Vita Plume Vice President/President Elect Editorial Assistance: Roxane Shaughnessy (TSA President) [email protected] Elena Phipps Our Mission Past President [email protected] The Textile Society of America is a 501(c)3 nonprofit that provides an international forum for the exchange and dissemination of textile knowledge from artistic, cultural, economic, historic, Maleyne Syracuse political, social, and technical perspectives. -

Border Thinking

Publication Series of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna VOLUME 21 Border Thinking Marina Gržinić (Ed.) Border Thinking Disassembling Histories of Racialized Violence Border Thinking Disassembling Histories of Racialized Violence Marina Gržinić (Ed.) Publication Series of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna Eva Blimlinger, Andrea B. Braidt, Karin Riegler (Series Eds.) VOLUME 21 On the Publication Series We are pleased to present the latest volume in the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna’s publication series. The series, published in cooperation with our highly com- mitted partner Sternberg Press, is devoted to central themes of contemporary thought about art practices and theories. The volumes comprise contribu- tions on subjects that form the focus of discourse in art theory, cultural studies, art history, and research at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna and represent the quintessence of international study and discussion taking place in the respective fields. Each volume is published in the form of an anthology, edited by staff members of the academy. Authors of high international repute are invited to make contributions that deal with the respective areas of emphasis. Research activities such as international conferences, lecture series, institute- specific research focuses, or research projects serve as points of departure for the individual volumes. All books in the series undergo a single blind peer review. International re- viewers, whose identities are not disclosed to the editors of the volumes, give an in-depth analysis and evaluation for each essay. The editors then rework the texts, taking into consideration the suggestions and feedback of the reviewers who, in a second step, make further comments on the revised essays.