ESTD Child and Adolescent Treatment Guidelines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mapping the Dissociated Body

Lesley University DigitalCommons@Lesley Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences Expressive Therapies Capstone Theses (GSASS) Spring 5-16-2020 Mapping the Dissociated Body Elizabeth Hough [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/expressive_theses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Hough, Elizabeth, "Mapping the Dissociated Body" (2020). Expressive Therapies Capstone Theses. 239. https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/expressive_theses/239 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences (GSASS) at DigitalCommons@Lesley. It has been accepted for inclusion in Expressive Therapies Capstone Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Lesley. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Running Head: MAPPING THE DISSOCIATED BODY 1 Mapping the Dissociated Body Elizabeth Hough Lesley University Running Head: MAPPING THE DISSOCIATED BODY 2 Abstract This capstone thesis explored the use of body mapping and body scans as a tool for assessing and tracking somatic dissociation and embodiment. The researcher utilized a client- centered approach and mindfulness-based interventions and theory to ground the work with the clients. While there were a variety of questionnaire-based tools for assessing dissociation with clients, many of them were lacking in the somatic component of dissociation. The available assessments were also exclusively self-reported and written or verbal, which had the potential to result in biased reporting. Clients may have also struggled to identify their level of somatic dissociation due to an inherent disconnection or dismissal of their somatic experience. This research described two case studies in which body scans and body mapping were utilized as a method to assess and track the client’s level of body dissociation and embodiment. -

XELJANZ (Tofacitinib)

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION Psoriatic Arthritis (in combination with nonbiologic DMARDs) These highlights do not include all the information needed to use XELJANZ 5 mg twice daily or XELJANZ XR 11 mg once daily. (2.2) XELJANZ/XELJANZ XR safely and effectively. See full prescribing Recommended dosage in patients with moderate and severe renal information for XELJANZ. impairment or moderate hepatic impairment is XELJANZ 5 mg once daily. (2, 8.7, 8.8) ® XELJANZ (tofacitinib) tablets, for oral use Ulcerative Colitis ® XELJANZ XR (tofacitinib) extended-release tablets, for oral use XELJANZ 10 mg twice daily for at least 8 weeks; then 5 or 10 mg Initial U.S. Approval: 2012 twice daily. Discontinue after 16 weeks of 10 mg twice daily, if adequate therapeutic benefit is not achieved. Use the lowest effective dose to WARNING: SERIOUS INFECTIONS AND MALIGNANCY maintain response. (2.3) See full prescribing information for complete boxed warning. Recommended dosage in patients with moderate and severe renal impairment or moderate hepatic impairment: half the total daily dosage Serious infections leading to hospitalization or death, including recommended for patients with normal renal and hepatic function. (2, 8.7, tuberculosis and bacterial, invasive fungal, viral, and other 8.8) opportunistic infections, have occurred in patients receiving Dosage Adjustment XELJANZ. (5.1) See the full prescribing information for dosage adjustments by indication If a serious infection develops, interrupt XELJANZ/XELJANZ XR for patients receiving CYP2C19 and/or CYP3A4 inhibitors; in patients until the infection is controlled. (5.1) with moderate or severe renal impairment or moderate hepatic Prior to starting XELJANZ/XELJANZ XR, perform a test for latent impairment; and patients with lymphopenia, neutropenia, or anemia. -

1: Gastro-Intestinal System

1 1: GASTRO-INTESTINAL SYSTEM Antacids .......................................................... 1 Stimulant laxatives ...................................46 Compound alginate products .................. 3 Docuate sodium .......................................49 Simeticone ................................................... 4 Lactulose ....................................................50 Antimuscarinics .......................................... 5 Macrogols (polyethylene glycols) ..........51 Glycopyrronium .......................................13 Magnesium salts ........................................53 Hyoscine butylbromide ...........................16 Rectal products for constipation ..........55 Hyoscine hydrobromide .........................19 Products for haemorrhoids .................56 Propantheline ............................................21 Pancreatin ...................................................58 Orphenadrine ...........................................23 Prokinetics ..................................................24 Quick Clinical Guides: H2-receptor antagonists .......................27 Death rattle (noisy rattling breathing) 12 Proton pump inhibitors ........................30 Opioid-induced constipation .................42 Loperamide ................................................35 Bowel management in paraplegia Laxatives ......................................................38 and tetraplegia .....................................44 Ispaghula (Psyllium husk) ........................45 ANTACIDS Indications: -

Examining the Therapist's Internal Experience When a Patient Dissociates in Session

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Doctorate in Social Work (DSW) Dissertations School of Social Policy and Practice Spring 5-13-2013 Do You Know What I Know? Examining the Therapist's Internal Experience when a Patient Dissociates in Session Jacqueline R. Strait University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations_sp2 Part of the Psychology Commons, and the Social Work Commons Recommended Citation Strait, Jacqueline R., "Do You Know What I Know? Examining the Therapist's Internal Experience when a Patient Dissociates in Session" (2013). Doctorate in Social Work (DSW) Dissertations. 36. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations_sp2/36 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations_sp2/36 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Do You Know What I Know? Examining the Therapist's Internal Experience when a Patient Dissociates in Session Abstract There is rich theoretical literature that cites the importance of the therapist’s use of self as a way of knowing, especially in cases where a patient has been severely traumatized in early life. There is limited empirical research that explores the in-session experience of therapists working with traumatized patients in order to support these claims. This study employed a qualitative design to explore a therapist’s internal experience when a patient dissociates in session. The aim of this study was to further develop the theoretical construct of dissociative attunement to explain the way that therapist and patient engage in a nonverbal process of synchronicity that has the potential to communicate dissociated images, affect or somatosensory experiences by way of the therapist’s internal experience. -

Ce4less.Com Ce4less.Com Ce4less.Com Ce4less.Com Ce4less.Com Ce4less.Com Ce4less.Com

Hallucinogens And Dissociative Drug Use And Addiction Introduction Hallucinogens are a diverse group of drugs that cause alterations in perception, thought, or mood. This heterogeneous group has compounds with different chemical structures, different mechanisms of action, and different adverse effects. Despite their description, most hallucinogens do not consistently cause hallucinations. The drugs are more likely to cause changes in mood or in thought than actual hallucinations. Hallucinogenic substances that form naturally have been used worldwide for millennia to induce altered states for religious or spiritual purposes. While these practices still exist, the more common use of hallucinogens today involves the recreational use of synthetic hallucinogens. Hallucinogen And Dissociative Drug Toxicity Hallucinogens comprise a collection of compounds that are used to induce hallucinations or alterations of consciousness. Hallucinogens are drugs that cause alteration of visual, auditory, or tactile perceptions; they are also referred to as a class of drugs that cause alteration of thought and emotion. Hallucinogens disrupt a person’s ability to think and communicate effectively. Hallucinations are defined as false sensations that have no basis in reality: The sensory experience is not actually there. The term “hallucinogen” is slightly misleading because hallucinogens do not consistently cause hallucinations. 1 ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com How hallucinogens cause alterations in a person’s sensory experience is not entirely understood. Hallucinogens work, at least in part, by disrupting communication between neurotransmitter systems throughout the body including those that regulate sleep, hunger, sexual behavior and muscle control. Patients under the influence of hallucinogens may show a wide range of unusual and often sudden, volatile behaviors with the potential to rapidly fluctuate from a relaxed, euphoric state to one of extreme agitation and aggression. -

Pharmacology/Therapeutics II Block I Lectures – 2013‐14

Pharmacology/Therapeutics II Block I Lectures – 2013‐14 54. H2 Blocker, PPls – Patel 55. Principles of Clinical Toxicology – Kennedy 56. Anti‐Parasitic Agents – Johnson (To be posted later) 57. Palliation of Constipation & Nausea/vomiting – Kristopaitis (Lecture in Room 190) Tarun B. Patel, Ph.D Date: January 9, 2013: 10:30 a.m. Reading Assignment: Katzung, Basic and Clinical Pharmacology, 11th Edition, pp. 1067-1077. KEY CONCEPTS AND LEARNING OBJECTIVES Histamine via its different receptors produces a number of physiological and pathological actions. Therefore, anti-histaminergic drugs may be used to treat different conditions. 1. To know the physiological functions of histamine. 2. To understand which histamine receptors mediate the different effects of histamine in stomach ulcers. 3. To know what stimuli cause the release of histamine and acid in stomach. 4. To know the types of histamine H2 receptor antagonists that are available clinically. 5. To know the clinical uses of H2 receptor antagonists. 6. To know the drug interactions associated with the use of H2 receptor antagonists. 7. To understand the mechanism of action of PPIs 8. To know the adverse effects and drugs interactions with PPIs 9. To know the role of H. pylori in gastric ulceration 10. To know the drugs used to treat H. pylori infection Drug List: See Summary Table Provided at end of handout. Page 1 Tarun B. Patel, Ph.D Histamine H2 receptor antagonists and PPIs in the treatment of GI Ulcers: The following section covers medicines used to treat ulcer. These medicines include H2 receptor antagonists, proton pump inhibitors, mucosal protective agents and antibiotics (for treatment of H. -

Enhanced Anticoagulation Activity of Functional RNA Origami

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.29.319590; this version posted October 1, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Enhanced Anticoagulation Activity of Functional RNA Origami Abhichart Krissanaprasit, Carson M. Key, Kristen Froehlich, Sahil Pontula, Emily Mihalko, Daniel M. Dupont, Ebbe S. Andersen, Jørgen Kjems, Ashley C. Brown, and Thomas H. LaBean* Dr. A Krissanaprasit, C. M. Key, Prof. T. H. LaBean Department of Materials Science and Engineering, College of Engineering, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, 27695, USA. E-mail: [email protected] K. Froehlich, E. Mihalko, Prof. A. C. Brown Joint Department of Biomedical Engineering, College of Engineering, North Carolina State University and University of North Carolina - Chapel Hill, Raleigh, NC, 27695, USA. S. Pontula William G. Enloe High School, Raleigh, NC 27610, USA Dr. D. M. Dupont, Prof. E. S. Andersen, Prof. J. Kjems Interdisciplinary Nanoscience Center (iNANO), Aarhus University, 8000 Aarhus C, Denmark Prof. A. C. Brown, Prof. T. H. LaBean Comparative Medicine Institute, North Carolina State University and University of North Carolina - Chapel Hill, Raleigh, NC, 27695, USA. Keywords: anticoagulant, RNA origami, nucleic acid, RNA nanotechnology, aptamer, direct thrombin inhibitor, reversal agent 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.29.319590; this version posted October 1, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract Anticoagulants are commonly utilized during surgeries and to treat thrombotic diseases like stroke and deep vein thrombosis. -

Treatment for Calcium Channel Blocker Poisoning: a Systematic Review

Clinical Toxicology (2014), 52, 926–944 Copyright © 2014 Informa Healthcare USA, Inc. ISSN: 1556-3650 print / 1556-9519 online DOI: 10.3109/15563650.2014.965827 REVIEW ARTICLE Treatment for calcium channel blocker poisoning: A systematic review M. ST-ONGE , 1,2,3 P.-A. DUB É , 4,5,6 S. GOSSELIN ,7,8,9 C. GUIMONT , 10 J. GODWIN , 1,3 P. M. ARCHAMBAULT , 11,12,13,14 J.-M. CHAUNY , 15,16 A. J. FRENETTE , 15,17 M. DARVEAU , 18 N. LE SAGE , 10,14 J. POITRAS , 11,12 J. PROVENCHER , 19 D. N. JUURLINK , 1,20,21 and R. BLAIS 7 1 Ontario and Manitoba Poison Centre, Toronto, ON, Canada 2 Institute of Medical Science, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada 3 Department of Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada 4 Direction of Environmental Health and Toxicology, Institut national de sant é publique du Qu é bec, Qu é bec, QC, Canada 5 Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Qu é bec, Qu é bec, QC, Canada 6 Faculty of Pharmacy, Université Laval, Qu é bec, QC, Canada 7 Centre antipoison du Qu é bec, Qu é bec, QC, Canada 8 Department of Medicine, McGill University, Montr é al, QC, Canada 9 Toxicology Consulting Service, McGill University Health Centre, Montr é al, QC, Canada 10 Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Qu é bec, Qu é bec, QC, Canada 11 Centre de sant é et services sociaux Alphonse-Desjardins (CHAU de Lévis), L é vis, QC, Canada 12 Department of Family Medicine and Emergency Medicine, Universit é Laval, Québec, QC, Canada 13 Division de soins intensifs, Universit é Laval, Qu é bec, QC, Canada 14 Populations -

ABC of Poisoning. Emergency Drugs: Agents Used in the Treatment Of

1984 1AFnT('AT VOT. TmFT 289 22 SEPTEMBER UIQnTCTIT utILtjTOTTRMAT vJV' _- - . _ 742 D.ll.lilm13 4=.-, TIM MEREDITH JANE CAISLEY ABC ofPoisoning GLYN VOLANS EMERGENCY DRUGS: AGENTS USED IN THE TREATMENT OF POISONING A readily available and practical guide to the drugs used in the treatment of / poisoning is important, since many of the agents concerned are used infrequently; some can be obtained only from selected poisons treatment centres, and others, although listed in textbooks, are not available in the United Kingdom; still others are now considered obsolete and, in some cases, actually dangerous. The article Is basen advice Lists ofrecommended drugs have been published by the Department of appendixah artiendixsHto basedcrcularcircuon HNhen(78) Health and Social Security, most recently as HN(62)13 and HN(78)23. DrHuSS s 23 Ougs of Special Value in the1This article is based on these earlier lists, although, necessarily, many more Treatment of Poisoning in drugs have been included and additional information is given on the Accident and Emergency indications for use, mode ofaction, presentation, and dosage. In future this Departments list will be revised as necessary, and copies will be available from the National Poisons Information Service. Agents used for local cleansing, reliefofpain, fluid replacement, oxygen, and the more general care of the injured patient are not included. The need for collaboration and discussion between doctors and pharmacists in the preparation ofthis list is readily apparent and we would welcome comments which may be taken into account in future revisions. (1) Recommended agents that are readily available The decision to stock individual items will depend on the expected ofthe hospital concerned. -

Calcium and Beta Receptor Antagonist Overdose: a Review and Update of Pharmacological Principles and Management

Calcium and Beta Receptor Antagonist Overdose: A Review and Update of Pharmacological Principles and Management Christopher R. H. Newton, M.D.,1 Joao H. Delgado, M.D.,2 and Hernan F. Gomez, M.D.1 ABSTRACT Calcium channel and beta-adrenergic receptor antagonists are common pharma- ceutical agents with multiple overlapping clinical indications. When used appropriately, these agents are safe and efficacious. In overdose, however, these agents have the potential for serious morbidity. Calcium channel blockers and beta blockers share similar physio- logical effects on the cardiovascular system, such as hypotension and bradycardia, in over- dose and occasionally at therapeutic doses. The initial management for symptomatic overdose of both drug classes consists of supportive care measures. Other therapies in- cluding administration of glucagon, calcium, catecholamines, phosphodiesterase in- hibitors and insulin have been used with varying degrees of success. In addition, intra- aortic balloon pump and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation techniques have been successfully utilized in refractory cases. This article reviews beta blocker and calcium channel blocker pharmacological principles and updates current management strategies. KEYWORDS: Beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, overdose Objectives: Upon completion of this article, the reader should be able to: (1) discuss the mechanisms of action of clinically used cal- cium channel blockers and beta blockers and relate these effects to the toxicity seen with overdose; (2) describe the role for gastric decontamination following overdose; (3) understand the various therapies for the treatment of acute beta blocker and calcium chan- nel blocker toxicity and recognize their relative advantages and disadvantages. Accreditation: The University of Michigan is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continung Medical Education to sponsor continuing medical education for physicians. -

Antidote List

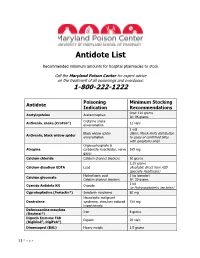

Antidote List Recommended minimum amounts for hospital pharmacies to stock Call the Maryland Poison Center for expert advice on the treatment of all poisonings and overdoses: 1-800-222-1222 Poisoning Minimum Stocking Antidote Indication Recommendations Oral: 120 grams Acetylcysteine Acetaminophen IV: 96 grams Crotaline snake Antivenin, snake (CroFab®) 12 vials envenomation 1 vial Black widow spider (Note: Merck limits distribution Antivenin, black widow spider envenomation to cases of confirmed bites with symptoms only) Organophosphate & Atropine carbamate insecticides, nerve 165 mg gases Calcium chloride Calcium channel blockers 10 grams 2.25 grams Calcium disodium EDTA Lead (Available direct from ASD Specialty Healthcare) Hydrofluoric acid 1 kg (powder) Calcium gluconate Calcium channel blockers IV: 30 grams 1 kit Cyanide Antidote Kit Cyanide (or Hydroxocobalamin, see below) Cyproheptadine (Periactin®) Serotonin syndrome 80 mg Neuroleptic malignant Dantrolene syndrome, stimulant-induced 720 mg hyperthermia Deferoxamine mesylate Iron 8 grams (Desferal®) Digoxin Immune FAB Digoxin 20 vials (Digibind®, DigiFab®) Dimercaprol (BAL) Heavy metals 1.5 grams 1 | P a g e Maryland Poison Center Antidote List – continued Poisoning Minimum Stocking Antidote Indication Recommendations DMSA (Succimer, Chemet®) Heavy metals 2000 mg Folic acid Methanol IV: 150 mg Flumazenil (Romazicon®) Benzodiazepines 10 mg Fomepizole (Antizol®) Ethylene glycol, methanol 12 grams Beta blockers, Glucagon 50 mg calcium channel blockers Hydroxocobalamin (Cyanokit®) Cyanide -

Antidotes in Poisoning Binila Chacko1, John V Peter2

INVITED ARTICLE Antidotes in Poisoning Binila Chacko1, John V Peter2 ABSTRACT Introduction: Antidotes are agents that negate the effect of a poison or toxin. Antidotes mediate its effect either by preventing the absorption of the toxin, by binding and neutralizing the poison, antagonizing its end-organ effect, or by inhibition of conversion of the toxin to more toxic metabolites. Antidote administration may not only result in the reduction of free or active toxin level, but also in the mitigation of end-organ effects of the toxin by mechanisms that include competitive inhibition, receptor blockade or direct antagonism of the toxin. Mechanism of action of antidotes: Reduction in free toxin level can be achieved by specific and non-specific agents that bind to the toxin. The most commonly used non-specific binding agent is activated charcoal. Specific binders include chelating agents, bioscavenger therapy and immunotherapy. In some situations, enhanced elimination can be achieved by urinary alkalization or hemadsorption. Competitive inhibition of enzymes (e.g. ethanol for methanol poisoning), enhancement of enzyme function (e.g. oximes for organophosphorus poisoning) and competitive receptor blockade (e.g. naloxone, flumazenil) are other mechanisms by which antidotes act. Drugs such as N-acetyl cysteine and sodium thiocyanate reduce the formation of toxic metabolites in paracetamol and cyanide poisoning respectively. Drugs such as atropine and magnesium are used to counteract the end-organ effects in organophosphorus poisoning. Vitamins such as vitamin K, folic acid and pyridoxine are used to antagonise the effects of warfarin, methotrexate and INH respectively in the setting of toxicity or overdose. This review provides an overview of the role of antidotes in poisoning.