Redalyc.A Fortuitous Ant-Fern Association in the Amazon Lowlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

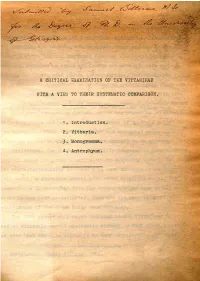

^ a Critical Examination of the Vittarieae with a View To

/ P u n -t/p '& . J9. ^ _ ^ 2 (tO. A CRITICAL EXAMINATION OF THE VITTARIEAE WITH A VIEW TO THEIR SYSTEMATIC COMPARISON. 1. Introduction. 2. Vittaria. 3. Monogramma, 4. Antrophyum. ProQuest Number: 13916247 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13916247 Published by ProQuest LLC(2019). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 INTRODUCTION. The Vittarieae, as described by Christensen (1), comprises five genera, viz. Vjfrfrftrja, Monogramma,. Antronhvum. Hecistopterist and Anetium. all of whicij are epiphytic forms growing in the damp forests of the Old and New;World Tropics. All of them possess creeping rhizomes on which the frortds are arranged more or less definitely in two rows on the dorsal surface. The fronds are simple in outline with the exception of those of Heoistonteris which are dichotomously branched. The venation of the fronds is reticulate except in Heoistonteris where there is an open, dichotomous system of veins^An interesting feature, which has proved to be valuable as a diagnostic character, is the presence of "spicule cells" in the epidermis. -

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

Epiphytes and the National Wetland Plant List

Lichvar, R.W. and W. Fertig. 2011. Epiphytes and the National Wetland Plant List. Phytoneuron 2011-16: 1–31. EPIPHYTES AND THE NATIONAL WETLAND PLANT LIST ROBERT W. LICHVAR U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory 72 Lyme Road Hanover, NH 03755-1290 WALTER FERTIG Moenave Botanical Consulting 1117 West Grand Canyon Drive Kanab, UT 84741 ABSTRACT The National Wetland Plant List (NWPL) is a list of species that occur in wetlands in the United States. It is a product of a collaborative effort of four Federal agencies: the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the Natural Resources Conservation Service. The NWPL has many uses, but it is specifically designed for use in wetland delineation for establishing the extent of Federal jurisdictional of wetland boundaries. To be listed in the NWPL, a plant must be rooted in soil, so there is a direct relationship between a plant’s occurrence and its preference for hydric soils. This relationship, coupled with the plant’s frequency of occurrence in wetlands, is used to place it in one of five categories representing the probability that the plant occurs in a wetland. Many species are considered to be epiphytes, but they represent various life forms, ranging from purely epiphytic to frequently occurring on the ground. Based on a literature review of 192 species across the United States and its territories, we determined which species fell into four categories of epiphytic life forms or are terrestrial and should not be considered epiphytes. -

Polypodiaceae (PDF)

This PDF version does not have an ISBN or ISSN and is not therefore effectively published (Melbourne Code, Art. 29.1). The printed version, however, was effectively published on 6 June 2013. Zhang, X. C., S. G. Lu, Y. X. Lin, X. P. Qi, S. Moore, F. W. Xing, F. G. Wang, P. H. Hovenkamp, M. G. Gilbert, H. P. Nooteboom, B. S. Parris, C. Haufler, M. Kato & A. R. Smith. 2013. Polypodiaceae. Pp. 758–850 in Z. Y. Wu, P. H. Raven & D. Y. Hong, eds., Flora of China, Vol. 2–3 (Pteridophytes). Beijing: Science Press; St. Louis: Missouri Botanical Garden Press. POLYPODIACEAE 水龙骨科 shui long gu ke Zhang Xianchun (张宪春)1, Lu Shugang (陆树刚)2, Lin Youxing (林尤兴)3, Qi Xinping (齐新萍)4, Shannjye Moore (牟善杰)5, Xing Fuwu (邢福武)6, Wang Faguo (王发国)6; Peter H. Hovenkamp7, Michael G. Gilbert8, Hans P. Nooteboom7, Barbara S. Parris9, Christopher Haufler10, Masahiro Kato11, Alan R. Smith12 Plants mostly epiphytic and epilithic, a few terrestrial. Rhizomes shortly to long creeping, dictyostelic, bearing scales. Fronds monomorphic or dimorphic, mostly simple to pinnatifid or 1-pinnate (uncommonly more divided); stipes cleanly abscising near their bases or not (most grammitids), leaving short phyllopodia; veins often anastomosing or reticulate, sometimes with included veinlets, or veins free (most grammitids); indument various, of scales, hairs, or glands. Sori abaxial (rarely marginal), orbicular to oblong or elliptic, occasionally elongate, or sporangia acrostichoid, sometimes deeply embedded, sori exindusiate, sometimes covered by cadu- cous scales (soral paraphyses) when young; sporangia with 1–3-rowed, usually long stalks, frequently with paraphyses on sporangia or on receptacle; spores hyaline to yellowish, reniform, and monolete (non-grammitids), or greenish and globose-tetrahedral, trilete (most grammitids); perine various, usually thin, not strongly winged or cristate. -

Epilist 1.0: a Global Checklist of Vascular Epiphytes

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2021 EpiList 1.0: a global checklist of vascular epiphytes Zotz, Gerhard ; Weigelt, Patrick ; Kessler, Michael ; Kreft, Holger ; Taylor, Amanda Abstract: Epiphytes make up roughly 10% of all vascular plant species globally and play important functional roles, especially in tropical forests. However, to date, there is no comprehensive list of vas- cular epiphyte species. Here, we present EpiList 1.0, the first global list of vascular epiphytes based on standardized definitions and taxonomy. We include obligate epiphytes, facultative epiphytes, and hemiepiphytes, as the latter share the vulnerable epiphytic stage as juveniles. Based on 978 references, the checklist includes >31,000 species of 79 plant families. Species names were standardized against World Flora Online for seed plants and against the World Ferns database for lycophytes and ferns. In cases of species missing from these databases, we used other databases (mostly World Checklist of Selected Plant Families). For all species, author names and IDs for World Flora Online entries are provided to facilitate the alignment with other plant databases, and to avoid ambiguities. EpiList 1.0 will be a rich source for synthetic studies in ecology, biogeography, and evolutionary biology as it offers, for the first time, a species‐level overview over all currently known vascular epiphytes. At the same time, the list represents work in progress: species descriptions of epiphytic taxa are ongoing and published life form information in floristic inventories and trait and distribution databases is often incomplete and sometimes evenwrong. -

Biogeographical Patterns of Species Richness, Range Size And

Biogeographical patterns of species richness, range size and phylogenetic diversity of ferns along elevational-latitudinal gradients in the tropics and its transition zone Kumulative Dissertation zur Erlangung als Doktorgrades der Naturwissenschaften (Dr.rer.nat.) dem Fachbereich Geographie der Philipps-Universität Marburg vorgelegt von Adriana Carolina Hernández Rojas aus Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexiko Marburg/Lahn, September 2020 Vom Fachbereich Geographie der Philipps-Universität Marburg als Dissertation am 10.09.2020 angenommen. Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Georg Miehe (Marburg) Zweitgutachterin: Prof. Dr. Maaike Bader (Marburg) Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 27.10.2020 “An overwhelming body of evidence supports the conclusion that every organism alive today and all those who have ever lived are members of a shared heritage that extends back to the origin of life 3.8 billion years ago”. This sentence is an invitation to reflect about our non- independence as a living beins. We are part of something bigger! "Eine überwältigende Anzahl von Beweisen stützt die Schlussfolgerung, dass jeder heute lebende Organismus und alle, die jemals gelebt haben, Mitglieder eines gemeinsamen Erbes sind, das bis zum Ursprung des Lebens vor 3,8 Milliarden Jahren zurückreicht." Dieser Satz ist eine Einladung, über unsere Nichtunabhängigkeit als Lebende Wesen zu reflektieren. Wir sind Teil von etwas Größerem! PREFACE All doors were opened to start this travel, beginning for the many magical pristine forest of Ecuador, Sierra de Juárez Oaxaca and los Tuxtlas in Veracruz, some of the most biodiverse zones in the planet, were I had the honor to put my feet, contemplate their beauty and perfection and work in their mystical forest. It was a dream into reality! The collaboration with the German counterpart started at the beginning of my academic career and I never imagine that this will be continued to bring this research that summarizes the efforts of many researchers that worked hardly in the overwhelming and incredible biodiverse tropics. -

Fern Classification

16 Fern classification ALAN R. SMITH, KATHLEEN M. PRYER, ERIC SCHUETTPELZ, PETRA KORALL, HARALD SCHNEIDER, AND PAUL G. WOLF 16.1 Introduction and historical summary / Over the past 70 years, many fern classifications, nearly all based on morphology, most explicitly or implicitly phylogenetic, have been proposed. The most complete and commonly used classifications, some intended primar• ily as herbarium (filing) schemes, are summarized in Table 16.1, and include: Christensen (1938), Copeland (1947), Holttum (1947, 1949), Nayar (1970), Bierhorst (1971), Crabbe et al. (1975), Pichi Sermolli (1977), Ching (1978), Tryon and Tryon (1982), Kramer (in Kubitzki, 1990), Hennipman (1996), and Stevenson and Loconte (1996). Other classifications or trees implying relationships, some with a regional focus, include Bower (1926), Ching (1940), Dickason (1946), Wagner (1969), Tagawa and Iwatsuki (1972), Holttum (1973), and Mickel (1974). Tryon (1952) and Pichi Sermolli (1973) reviewed and reproduced many of these and still earlier classifica• tions, and Pichi Sermolli (1970, 1981, 1982, 1986) also summarized information on family names of ferns. Smith (1996) provided a summary and discussion of recent classifications. With the advent of cladistic methods and molecular sequencing techniques, there has been an increased interest in classifications reflecting evolutionary relationships. Phylogenetic studies robustly support a basal dichotomy within vascular plants, separating the lycophytes (less than 1 % of extant vascular plants) from the euphyllophytes (Figure 16.l; Raubeson and Jansen, 1992, Kenrick and Crane, 1997; Pryer et al., 2001a, 2004a, 2004b; Qiu et al., 2006). Living euphyl• lophytes, in turn, comprise two major clades: spermatophytes (seed plants), which are in excess of 260 000 species (Thorne, 2002; Scotland and Wortley, Biology and Evolution of Ferns and Lycopliytes, ed. -

Systematics and Biogeography of the Clusioid Clade (Malpighiales) Brad R

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass Biological Sciences Faculty and Staff Research Biological Sciences January 2011 Systematics and Biogeography of the Clusioid Clade (Malpighiales) Brad R. Ruhfel Eastern Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://encompass.eku.edu/bio_fsresearch Part of the Plant Biology Commons Recommended Citation Ruhfel, Brad R., "Systematics and Biogeography of the Clusioid Clade (Malpighiales)" (2011). Biological Sciences Faculty and Staff Research. Paper 3. http://encompass.eku.edu/bio_fsresearch/3 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Biological Sciences at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biological Sciences Faculty and Staff Research by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HARVARD UNIVERSITY Graduate School of Arts and Sciences DISSERTATION ACCEPTANCE CERTIFICATE The undersigned, appointed by the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology have examined a dissertation entitled Systematics and biogeography of the clusioid clade (Malpighiales) presented by Brad R. Ruhfel candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy and hereby certify that it is worthy of acceptance. Signature Typed name: Prof. Charles C. Davis Signature ( ^^^M^ *-^£<& Typed name: Profy^ndrew I^4*ooll Signature / / l^'^ i •*" Typed name: Signature Typed name Signature ^ft/V ^VC^L • Typed name: Prof. Peter Sfe^cnS* Date: 29 April 2011 Systematics and biogeography of the clusioid clade (Malpighiales) A dissertation presented by Brad R. Ruhfel to The Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Biology Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2011 UMI Number: 3462126 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Common Epiphytes and Lithophytes of BELIZE 1 Bruce K

Common Epiphytes and Lithophytes of BELIZE 1 Bruce K. Holst, Sally Chambers, Elizabeth Gandy & Marilynn Shelley1 David Amaya, Ella Baron, Marvin Paredes, Pascual Garcia & Sayuri Tzul2 1Marie Selby Botanical Gardens, 2 Ian Anderson’s Caves Branch Botanical Garden © Marie Selby Bot. Gard. ([email protected]), Ian Anderson’s Caves Branch Bot. Gard. ([email protected]). Photos by David Amaya (DA), Ella Baron (EB), Sally Chambers (SC), Wade Coller (WC), Pascual Garcia (PG), Elizabeth Gandy (EG), Bruce Holst (BH), Elma Kay (EK), Elizabeth Mallory (EM), Jan Meerman (JM), Marvin Paredes (MP), Dan Perales (DP), Phil Nelson (PN), David Troxell (DT) Support from the Marie Selby Botanical Gardens, Ian Anderson’s Caves Branch Jungle Lodge, and many more listed in the Acknowledgments [fieldguides.fieldmuseum.org] [1179] version 1 11/2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS long the eastern slopes of the Andes and in Brazil’s Atlantic P. 1 ............. Epiphyte Overview Forest biome. In these places where conditions are favorable, epiphytes account for up to half of the total vascular plant P. 2 .............. Epiphyte Adaptive Strategies species. Worldwide, epiphytes account for nearly 10 percent P. 3 ............. Overview of major epiphytic plant families of all vascular plant species. Epiphytism (the ability to grow P. 6 .............. Lesser known epiphytic plant families as an epiphyte) has arisen many times in the plant kingdom P. 7 ............. Common epiphytic plant families and species around the world. (Pteridophytes, p. 7; Araceae, p. 9; Bromeliaceae, p. In Belize, epiphytes are represented by 34 vascular plant 11; Cactaceae, p. 15; p. Gesneriaceae, p. 17; Orchida- families which grow abundantly in many shrublands and for- ceae, p. -

A Revised Generic Classification of Vittarioid Ferns (Pteridaceae)

Schuettpelz & al. • Revised classification of vittarioid ferns TAXON 65 (4) • August 2016: 708–722 A revised generic classification of vittarioid ferns (Pteridaceae) based on molecular, micromorphological, and geographic data Eric Schuettpelz,1 Cheng-Wei Chen,2 Michael Kessler,3 Jerald B. Pinson,4 Gabriel Johnson,1 Alex Davila,5 Alyssa T. Cochran,6 Layne Huiet7 & Kathleen M. Pryer7 1 Department of Botany, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. 20013, U.S.A. 2 Division of Botanical Garden, Taiwan Forestry Research Institute, Taipei 10066, Taiwan 3 Institute of Systematic Botany, University of Zurich, 8008 Zurich, Switzerland 4 Department of Biology, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32611, U.S.A. 5 Department of Biology and Marine Biology, University of North Carolina Wilmington, Wilmington, North Carolina 28403, U.S.A. 6 Department of Biology, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado 80523, U.S.A. 7 Department of Biology, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina 27708, U.S.A. Author for correspondence: Eric Schuettpelz, [email protected] ORICD ES, http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3891-9904 DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.12705/654.2 Abstract Vittarioid ferns compose a well-supported clade of 100–130 species of highly simplified epiphytes in the family Pterid- aceae. Generic circumscriptions within the vittarioid clade were among the first in ferns to be evaluated and revised based on molecular phylogenetic data. Initial analyses of rbcL sequences revealed strong geographic structure and demonstrated that the two largest vittarioid genera, as then defined, each had phylogenetically distinct American and Old World components. The results of subsequent studies that included as many as 36 individuals of 33 species, but still relied on a single gene, were generally consistent with the early findings. -

Epiphytic and Lithophytic Fern and Lycophyte Genera of 1 BELIZE Sally M

Epiphytic and Lithophytic Fern and Lycophyte Genera of 1 BELIZE Sally M. Chambers1, Bruce K. Holst1, Ella Baron2, David Amaya2& Marvin Paredes2 1Marie Selby Botanical Gardens, 2 Ian Anderson’s Caves Branch Botanical Garden © Marie Selby Botanical Gardens [[email protected]], Ian Anderson’s Caves Branch Botanical Garden ([email protected]). Photos by D. Amaya (DA), E. Baron (EB), B. Holst (BH), J. Meerman (JM), R. Moran (RM), P. Nelson (PN), M. Sundue (MS). Produced by Juliana Philipp and the authors. Support from the Marie Selby Botanical Gardens, Ian Anderson’s Caves Branch Jungle Lodge, Environmental Resource Institute - University of Belize [fieldguides.fieldmuseum.org] [1005] version 1 4/2018 Of the 79 fern and lycophyte genera known from Belize, 34 grow exclusively, or in part as epiphytes on trees and shrubs, as lithophytes on rocks, or as hemiepiphytes living in the canopy but maintain connection to the forest floor. These genera are distinguished based on frond shape, sori, growth habit, and rhizome characteristics. Definitions of these features, and the different characteristics they exhibit may be found at the end of this guide. Ferns and lycophytes (Phlegmariurus is the only known epiphytic lycophyte genus in Belize) can be distinguished by the presence of small leaves (microphylls) in lycophytes, the location in which the sori are produced (between stem and microphyll axes in lycophytes, on the underside, forks, or tips of fronds and microphylls in ferns) and differences in anatomical development. This guide provides brief descriptions for each genus, along with photographs displaying key characters for identification. The number of species for each genus found within Belize is provided in parentheses following the genus name. -

Floristic Survey of Vascular Plant in the Submontane Forest of Mt

BIODIVERSITAS ISSN: 1412-033X Volume 20, Number 8, August 2019 E-ISSN: 2085-4722 Pages: 2197-2205 DOI: 10.13057/biodiv/d200813 Short Communication: Floristic survey of vascular plant in the submontane forest of Mt. Burangrang Nature Reserve, West Java, Indonesia TRI CAHYANTO1,♥, MUHAMMAD EFENDI2,♥♥, RICKY MUSHOFFA SHOFARA1, MUNA DZAKIYYAH1, NURLAELA1, PRIMA G. SATRIA1 1Department of Biology, Faculty of Science and Technology,Universitas Islam Negeri Sunan Gunung Djati Bandung. Jl. A.H. Nasution No. 105, Cibiru,Bandung 40614, West Java, Indonesia. Tel./fax.: +62-22-7800525, email: [email protected] 2Cibodas Botanic Gardens, Indonesian Institute of Sciences. Jl. Kebun Raya Cibodas, Sindanglaya, Cipanas, Cianjur 43253, West Java, Indonesia. Tel./fax.: +62-263-512233, email: [email protected] Manuscript received: 1 July 2019. Revision accepted: 18 July 2019. Abstract. Cahyanto T, Efendi M, Shofara RM. 2019. Short Communication: Floristic survey of vascular plant in the submontane forest of Mt. Burangrang Nature Reserve, West Java, Indonesia. Biodiversitas 20: 2197-2205. A floristic survey was conducted in submontane forest of Block Pulus Mount Burangrang West Java. The objectives of the study were to inventory vascular plant and do quantitative measurements of floristic composition as well as their structure vegetation in the submontane forest of Nature Reserves Mt. Burangrang, Purwakarta West Java. Samples were recorded using exploration methods, in the hiking traill of Mt. Burangrang, from 946 to 1110 m asl. Vegetation analysis was done using sampling plots methods, with plot size of 500 m2 in four locations. Result was that 208 species of vascular plant consisting of basal family of angiosperm (1 species), magnoliids (21 species), monocots (33 species), eudicots (1 species), superrosids (1 species), rosids (74 species), superasterids (5 species), and asterids (47), added with 25 species of pterydophytes were found in the area.