This Is Not an Album for the Fainthearted, the Straitlaced, Or the Stylistically Correct

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

QUASIMODE: Ike QUEBEC

This discography is automatically generated by The JazzOmat Database System written by Thomas Wagner For private use only! ------------------------------------------ QUASIMODE: "Oneself-Likeness" Yusuke Hirado -p,el p; Kazuhiro Sunaga -b; Takashi Okutsu -d; Takahiro Matsuoka -perc; Mamoru Yonemura -ts; Mitshuharu Fukuyama -tp; Yoshio Iwamoto -ts; Tomoyoshi Nakamura -ss; Yoshiyuki Takuma -vib; recorded 2005 to 2006 in Japan 99555 DOWN IN THE VILLAGE 6.30 99556 GIANT BLACK SHADOW 5.39 99557 1000 DAY SPIRIT 7.02 99558 LUCKY LUCIANO 7.15 99559 IPE AMARELO 6.46 99560 SKELETON COAST 6.34 99561 FEELIN' GREEN 5.33 99562 ONESELF-LIKENESS 5.58 99563 GET THE FACT - OUTRO 1.48 ------------------------------------------ Ike QUEBEC: "The Complete Blue Note Forties Recordings (Mosaic 107)" Ike Quebec -ts; Roger Ramirez -p; Tiny Grimes -g; Milt Hinton -b; J.C. Heard -d; recorded July 18, 1944 in New York 34147 TINY'S EXERCISE 3.35 Blue Note 6507 37805 BLUE HARLEM 4.33 Blue Note 37 37806 INDIANA 3.55 Blue Note 38 39479 SHE'S FUNNY THAT WAY 4.22 --- 39480 INDIANA 3.53 Blue Note 6507 39481 BLUE HARLEM 4.42 Blue Note 544 40053 TINY'S EXERCISE 3.36 Blue Note 37 Jonah Jones -tp; Tyree Glenn -tb; Ike Quebec -ts; Roger Ramirez -p; Tiny Grimes -g; Oscar Pettiford -b; J.C. Heard -d; recorded September 25, 1944 in New York 37810 IF I HAD YOU 3.21 Blue Note 510 37812 MAD ABOUT YOU 4.11 Blue Note 42 39482 HARD TACK 3.00 Blue Note 510 39483 --- 3.00 prev. unissued 39484 FACIN' THE FACE 3.48 --- 39485 --- 4.08 Blue Note 42 Ike Quebec -ts; Napoleon Allen -g; Dave Rivera -p; Milt Hinton -b; J.C. -

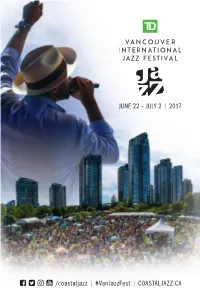

Jazz-Fest-2017-Program-Guide.Pdf

JUNE 22 – JULY 2 | 2017 /coastaljazz | #VanJazzFest | COASTALJAZZ.CA 20TH ANNIVERSARY SEASON 2017 181 CHAN CENTRE PRESENTS SERIES The Blind Boys of Alabama with Ben Heppner I SEP 23 The Gloaming I OCT 15 Zakir Hussain and Dave Holland: Crosscurrents I OCT 28 Ruthie Foster, Jimmie Dale Gilmore and Carrie Rodriguez I NOV 8 The Jazz Epistles: Abdullah Ibrahim and Hugh Masekela I FEB 18 Lila Downs I MAR 10 Daymé Arocena and Roberto Fonseca I APR 15 Circa: Opus I APR 28 BEYOND WORDS SERIES Kate Evans: Threads I SEP 29 Tanya Tagaq and Laakkuluk Williamson Bathory I MAR 16+17 SUBSCRIPTIONS ON SALE MAY 2 DAYMÉ AROCENA THE BLIND BOYS OF ALABAMA HUGH MASEKELA TANYA TAGAQ chancentre.com Welcome to the 32nd Annual TD Vancouver International Jazz Festival TD is pleased to bring you the 2017 TD Vancouver International Jazz Festival, a widely loved and cherished world-class event celebrating talented and culturally diverse artists from Canada and around the world. In Vancouver, we share a love of music — it is a passion that brings us together and enriches our lives. Music is powerful. It can transport us to faraway places or trigger a pleasant memory. Music is also one of many ways that TD connects with customers and communities across the country. And what better way to come together than to celebrate music at several major music festivals from Victoria to Halifax. ousands of fans across British Columbia — including me — look forward to this event every year. I’m excited to take in the music by local and international talent and enjoy the great celebration this festival has to o er. -

Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: the Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa

STYLISTIC EVOLUTION OF JAZZ DRUMMER ED BLACKWELL: THE CULTURAL INTERSECTION OF NEW ORLEANS AND WEST AFRICA David J. Schmalenberger Research Project submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Percussion/World Music Philip Faini, Chair Russell Dean, Ph.D. David Taddie, Ph.D. Christopher Wilkinson, Ph.D. Paschal Younge, Ed.D. Division of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2000 Keywords: Jazz, Drumset, Blackwell, New Orleans Copyright 2000 David J. Schmalenberger ABSTRACT Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: The Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa David J. Schmalenberger The two primary functions of a jazz drummer are to maintain a consistent pulse and to support the soloists within the musical group. Throughout the twentieth century, jazz drummers have found creative ways to fulfill or challenge these roles. In the case of Bebop, for example, pioneers Kenny Clarke and Max Roach forged a new drumming style in the 1940’s that was markedly more independent technically, as well as more lyrical in both time-keeping and soloing. The stylistic innovations of Clarke and Roach also helped foster a new attitude: the acceptance of drummers as thoughtful, sensitive musical artists. These developments paved the way for the next generation of jazz drummers, one that would further challenge conventional musical roles in the post-Hard Bop era. One of Max Roach’s most faithful disciples was the New Orleans-born drummer Edward Joseph “Boogie” Blackwell (1929-1992). Ed Blackwell’s playing style at the beginning of his career in the late 1940’s was predominantly influenced by Bebop and the drumming vocabulary of Max Roach. -

Michael Schade at a Special Release of His New Hyperion Recording “Of Ladies and Love...”

th La Scena Musicale cene English Canada Special Edition September - October 2002 Issue 01 Classical Music & Jazz Season Previews & Calendar Southern Ontario & Western Canada MichaelPerpetual Schade Motion Canada Post Publications Mail Sales Agreement n˚. 40025257 FREE TMS 1-01/colorpages 9/3/02 4:16 PM Page 2 Meet Michael Schade At a Special Release of his new Hyperion recording “Of ladies and love...” Thursday Sept.26 At L’Atelier Grigorian Toronto 70 Yorkville Ave. 5:30 - 7:30 pm Saturday Sept. 28 At L’Atelier Grigorian Oakville 210 Lakeshore Rd.E. 1:00 - 3:00 pm The World’s Finest Classical & Jazz Music Emporium L’Atelier Grigorian g Yorkville Avenue, U of T Bookstore, & Oakville GLENN GOULD A State of Wonder- The Complete Goldberg Variations (S3K 87703) The Goldberg Variations are Glenn Gould’s signature work. He recorded two versions of Bach’s great composition—once in 1955 and again in 1981. It is a testament to Gould’s genius that he could record the same piece of music twice—so differently, yet each version brilliant in its own way. Glenn Gould— A State Of Wonder brings together both of Gould’s legendary performances of The Goldberg Variations for the first time in a deluxe, digitally remastered, 3-CD set. Sony Classical celebrates the 70th anniversary of Glenn Gould's birth with a collection of limited edition CDs. This beautifully packaged collection contains the cornerstones of Gould’s career that marked him as a genius of our time. A supreme intrepreter of Bach, these recordings are an essential addition to every music collection. -

Earshot Jazz

Tomasz Stanko: Jazz as a Synonym for Freedom b y P e t e r M o n a g h a n Tomasz Stanko, the preeminent Polish jazzman, and one of the greatest trumpeters in the art form, ever, has called Chet Baker “my first trumpet love, followed by Miles, who continued as my guru until his very end.” He also acknowledges the in fluence o f a wide variety of other trumpet innovators of the modern era: Clifford Brown, Kenny Dorham, Fats Navarro, Booker Little, Don Cherry... That pretty well covers the trumpet waterfront. But Stanko also nods to other essential jazz heroes: John Coltrane, Max Roach, Sonny Rollins, the Jazz Messengers... But you can get a further sense o f how the Polish trumpeter’s aesthetic works from his comment that “as far as my sound is concerned, I believe that [painter Vincent] Van Gogh, [saxophonist] Coleman Hawkins, [writer W illiam ] Faulkner, [trumpeter] Roy Eldridge, [artist Amedeo] M odigliani, [writer W illiam S.] Burroughs, and [trumpeter] Buck Clayton might have helped in its buildup.” Stanko once said: “Various media, such as film , theatre, painting, literature and poetry, as well as philosophy and humanity, in its broad sense, have had an effect on me as a composer, improviser, and artist.” This month, we’ll get another chance (Triple Door, March 19) to hear why Stanko has become, through 40 years o f play ing in many of the most important bands and moments of European jazz — in fact, of any jazz — a true individualist. He is, nonetheless, rooted in and resonant w ith the course of modern jazz. -

Emily Dickinson in Song

1 Emily Dickinson in Song A Discography, 1925-2019 Compiled by Georgiana Strickland 2 Copyright © 2019 by Georgiana W. Strickland All rights reserved 3 What would the Dower be Had I the Art to stun myself With Bolts of Melody! Emily Dickinson 4 Contents Preface 5 Introduction 7 I. Recordings with Vocal Works by a Single Composer 9 Alphabetical by composer II. Compilations: Recordings with Vocal Works by Multiple Composers 54 Alphabetical by record title III. Recordings with Non-Vocal Works 72 Alphabetical by composer or record title IV: Recordings with Works in Miscellaneous Formats 76 Alphabetical by composer or record title Sources 81 Acknowledgments 83 5 Preface The American poet Emily Dickinson (1830-1886), unknown in her lifetime, is today revered by poets and poetry lovers throughout the world, and her revolutionary poetic style has been widely influential. Yet her equally wide influence on the world of music was largely unrecognized until 1992, when the late Carlton Lowenberg published his groundbreaking study Musicians Wrestle Everywhere: Emily Dickinson and Music (Fallen Leaf Press), an examination of Dickinson's involvement in the music of her time, and a "detailed inventory" of 1,615 musical settings of her poems. The result is a survey of an important segment of twentieth-century music. In the years since Lowenberg's inventory appeared, the number of Dickinson settings is estimated to have more than doubled, and a large number of them have been performed and recorded. One critic has described Dickinson as "the darling of modern composers."1 The intriguing question of why this should be so has been answered in many ways by composers and others. -

Gerry Hemingway Quartet Press Kit (W/Herb Robertson and Mark

Gerry Hemingway Quartet Herb Robertson - trumpet Ellery Eskelin - tenor saxophone Mark Dresser- bass Gerry Hemingway – drums "Like the tightest of early jazz bands, this crew is tight enough to hang way loose. *****" John Corbett, Downbeat Magazine Gerry Hemingway, who developed and maintained a highly acclaimed quintet for over ten years, has for the past six years been concentrating his experienced bandleading talent on a quartet formation. The quartet, formed in 1997 has now toured regularly in Europe and America including a tour in the spring of 1998 with over forty performances across the entire country. “What I experienced night after night while touring the US was that there was a very diverse audience interested in uncompromising jazz, from young teenagers with hard core leanings who were drawn to the musics energy and edge, to an older generation who could relate to the rhythmic power, clearly shaped melodies and the spirit of musical creation central to jazz’s tradition that informs the majority of what we perform.” “The percussionist’s expressionism keeps an astute perspective on dimension. He can make you think that hyperactivity is accomplished with a hush. His foursome recently did what only a handful of indie jazzers do: barnstormed the U.S., drumming up business for emotional abstraction and elaborate interplay . That’s something ElIery Eskelin, Mark Dresser and Ray Anderson know all about.“ Jim Macnie Village Voice 10/98 "The Quartet played the compositions, stuffed with polyrhythms and counterpoints, with a swinging -

Press Kit 2015

minasi_bio_4-30-2019_Layout 1 4/30/19 11:22 PM Page 1 BIOGRAPHY “Improvising musicians all pay lip service to the idea of working without a net, but most end up building safety precautions —no matter how slight or subtle they may be—into their work. Dom Minasi, however, isn't one of those musicians. The indefatigable guitarist has no interest in sonic safeguards or insurance. He's a law unto himself, creating music that speaks to his intelligence, fearlessness, and mischievous nature. And while Minasi has been at it for half a century, he shows no sign of slowing down or taking an easy road. Minasi is one of the great creative guitar artists operating today”. Dan Bilawsky from All About Jazz. Dom Minasi has been playing guitar for over 50 years. He became a professional musician playing jazz when he was 15 years old. In 1962 he started teaching and working as a full–time musician. In 1974, he was signed to Blue Note Records. After two albums he left the recording business and did not record again as a leader till 1999 for CIMP records. Between those years he made his living composing, authoring three books on harmony and improvisation, teaching and arranging. During the late seventies he did have an opportunity to work and perform with a whole slew of jazz giants including Arnie Lawrence, George Coleman, Frank Foster, Jimmy Heath and Dave Brubeck. After working with and being inspired by Roger Kellaway in ‘74, Dom began seriously composing in all genres’, including songwriting (both music & lyrics) jazz tunes and serious long hair contemporary pieces. -

Gerry Hemingway Quartet

Gerry Hemingway Quartet Herb Robertson - trumpet Matthias Schubert - tenor saxophone Mark Helias - bass Gerry Hemingway – drums "Like the tightest of early jazz bands, this crew is tight enough to hang way loose. *****" John Corbett, Downbeat Magazine Gerry Hemingway, who developed and maintained a highly acclaimed quintet for over ten years, has for the past six years been concentrating his experienced bandleading talent on a quartet formation. The quartet, formed in 1997 has now toured regularly in Europe and America including a tour in the spring of 1998 with over forty performances across the entire country. “What I experienced night after night while touring the US was that there was a very diverse audience interested in uncompromising jazz, from young teenagers with hard core leanings who were drawn to the musics energy and edge, to an older generation who could relate to the rhythmic power, clearly shaped melodies and the spirit of musical creation central to jazz’s tradition that informs the majority of what we perform.” “The percussionist’s expressionism keeps an astute perspective on dimension. He can make you think that hyperactivity is accomplished with a hush. His foursome recently did what only a handful of indie jazzers do: barnstormed the U.S., drumming up business for emotional abstraction and elaborate interplay . That’s something ElIery Eskelin, Mark Dresser and Ray Anderson know all about.“ Jim Macnie Village Voice 10/98 "The Quartet played the compositions, stuffed with polyrhythms and counterpoints, with a swinging -

April 2015 Vol

A Mirror and Focus for the Jazz Community April 2015 Vol. 31, No. 04 EARSHOT JAZZSeattle, Washington Golden Ear Award Recipients Photo by Daniel Sheehan Front Row: Greta Matassa, Ivan Arteaga, Chris Icasiano, Neil Welch Second Row: Nick Rogstad, Levi Gillis, Carmen Rothwell Back Row: Laurie de Koch, Brennan Carter, Evan Smith, Jacob Zimmerman, Josh Rawlings, Evan Flory-Barnes, Amy Denio 2 • Earshot Jazz • April 2015 EarsHOT JazZ LETTer frOM THE DirecTOR A Mirror and Focus for the Jazz Community Executive Director John Gilbreath Managing Director Karen Caropepe The Beat Goes On Programs Assistant Caitlin Peterkin Earshot Jazz Editors Schraepfer Harvey, Every month is Jazz Appreciation Caitlin Peterkin Month around here. The recent Contributing Writers Edan Kroliwecz, Andrew weeks have been so rich with inspira- Luthringer tional moments for Seattle jazz that Calendar Editors Halynn Blanchard, announcements of metrics on the Schraepfer Harvey U.S. jazz economy’s slip to only 1.4% Calendar Volunteer Tim Swetonic of the total music “industry” barely Photography Daniel Sheehan caused a ripple. With Garfield, Roos- Layout Caitlin Peterkin evelt, and Mt. Si high schools going Distribution Dan Wight and volunteers to New York next month for Essen- send Calendar Information to: tially Ellington, and so many area email [email protected] or students falling in love with the heart JOHN GILBREATH PHOTO BY BILL UZNAY go to www.earshot.org/Calendar/data/ of the art form, the future of jazz can gigsubmit.asp to submit online only be bright. cians like Christine Jensen, Bill Hol- Board of Directors Ruby Smith Love Seattle’s devotion to jazz education man, Robin Eubanks, Kneebody, (president), Diane Wah (vice president), Sally has been in full bloom this spring, Nichols (secretary), Sue Coliton, John W. -

Sylvie Courvoisier Trio with Kenny Wollesen & Drew Gress

! ! Sylvie Courvoisier Trio with Kenny Wollesen & Drew Gress ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !www.sylviecourvoisier.com ! ! ! ! ! !! The Sylvie Courvoisier Trio – a New Band That Sees the Pianist Joined by Top-Flight Bassist Drew Gress & Drummer Kenny Wollesen “That Sylvie Courvoisier’s music is as aesthetically beautiful as it is strange and mysterious is only further testament to her prowess as a composer.” — All Music Guide ! Sylvie Courvoisier steps out with her long awaited first recording for piano trio! One of the most creative pianists in the downtown scene, and a long time collaborator of Mark Feldman, Ikue Mori and many others, Sylvie combines a brilliant technique with a wild imagination that straddles classical, jazz, improvisation and more. Featuring the dynamic rhythm section of Kenny Wollesen and Drew Gress, the music combines the best of impro- visation and composition in the classic piano trio format. Three years in the making this is !an essential project that highlights an exciting new musical world. ! !About her new trio, Courvoisier says: “ FOR many years John Zorn has been asking me to form a piano trio—but I always felt in- timidated by its long and powerful history. Finding the right musicians to work with was of course essential, and I tried many different combos before settling on this one. Drew and Kenny are definitely the right trio—being both beautiful players and beautiful people. Drew has a gorgeous sound and a unique rhythmic sensibility, and Kenny has such a wonderful sense of groove and a huge dynamic range. This music -

Remise Des Prix 2010

Remise des Prix 2010 Lausanne, le 25 septembre 2010 Salle du Grand Conseil, Aula du Palais de Rumine La Fondation Vaudoise pour la Culture est financée par l’Etat de Vaud, qui l’a créée en 1987. L’attribution des Prix 2010 bénéficie en outre du soutien de : Fondation Vaudoise pour la Culture Remise des Prix du 25 septembre 2010 SOMMAIRE Notices biographiques des lauréates et lauréats Sylvie COURVOISIER, pianiste, compositeur, Grand Prix 2 Nicolas RABOUD, historien de l’art et directeur artistique, Prix de l’Eveil 5 René GONZALEZ, directeur du Théâtre Vidy-Lausanne, Prix du Rayonnement 9 Kei KOITO, musicienne, organiste, Prix culturel vaudois Musique 12 Collectif CIRCUIT, centre d’art contemporain, Prix culturel vaudois Arts Visuels 16 Yasmine CHAR, écrivaine, Prix culturel vaudois Littérature 23 Informations sur la Fondation Vaudoise pour la Culture Conseil de Fondation 25 Objectifs et définition des Prix 25 Compagnonnage renforcé entre l’Etat et les sponsors privés 26 L’ensemble des Prix remis par la Fondation se trouve sur notre site Internet http://www.fvpc.ch 1 Fondation Vaudoise pour la Culture Remise des Prix du 25 septembre 2010 GRAND PRIX 2010 SYLVIE COURVOISIER Elle parcourt la planète en tous sens tout en cultivant ses racines ; elle est devenue new- yorkaise tout en gardant ses profondes attaches avec le canton de Vaud ; elle est fondamentalement sans frontières, comme sa musique, et son piano est une machine extraordinaire au service de son univers musical : elle compose et crée comme d’autres explorent des mondes inconnus, et l’on ne saurait étiqueter cette galaxie de sonorités en perpétuelle recherche.