268 CACTUS and SUCCULENT JOURNAL (U.S.), Vol. 66 (1994

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecology and Conservation of the Cactus Ferruginous Pygmy-Owl in Arizona

United States Department of Agriculture Ecology and Conservation Forest Service Rocky Mountain of the Cactus Ferruginous Research Station General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-43 Pygmy-Owl in Arizona January 2000 Abstract ____________________________________ Cartron, Jean-Luc E.; Finch, Deborah M., tech. eds. 2000. Ecology and conservation of the cactus ferruginous pygmy-owl in Arizona. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-43. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 68 p. This report is the result of a cooperative effort by the Rocky Mountain Research Station and the USDA Forest Service Region 3, with participation by the Arizona Game and Fish Department and the Bureau of Land Management. It assesses the state of knowledge related to the conservation status of the cactus ferruginous pygmy-owl in Arizona. The population decline of this owl has been attributed to the loss of riparian areas before and after the turn of the 20th century. Currently, the cactus ferruginous pygmy-owl is chiefly found in southern Arizona in xeroriparian vegetation and well- structured upland desertscrub. The primary threat to the remaining pygmy-owl population appears to be continued habitat loss due to residential development. Important information gaps exist and prevent a full understanding of the current population status of the owl and its conservation needs. Fort Collins Service Center Telephone (970) 498-1392 FAX (970) 498-1396 E-mail rschneider/[email protected] Web site http://www.fs.fed.us/rm Mailing Address Publications Distribution Rocky Mountain Research Station 240 W. Prospect Road Fort Collins, CO 80526-2098 Cover photo—Clockwise from top: photograph of fledgling in Arizona by Jean-Luc Cartron, photo- graph of adult ferruginous pygmy-owl in Arizona by Bob Miles, photograph of adult cactus ferruginous pygmy-owl in Texas by Glenn Proudfoot. -

Plethora of Plants - Collections of the Botanical Garden, Faculty of Science, University of Zagreb (2): Glasshouse Succulents

NAT. CROAT. VOL. 27 No 2 407-420* ZAGREB December 31, 2018 professional paper/stručni članak – museum collections/muzejske zbirke DOI 10.20302/NC.2018.27.28 PLETHORA OF PLANTS - COLLECTIONS OF THE BOTANICAL GARDEN, FACULTY OF SCIENCE, UNIVERSITY OF ZAGREB (2): GLASSHOUSE SUCCULENTS Dubravka Sandev, Darko Mihelj & Sanja Kovačić Botanical Garden, Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, University of Zagreb, Marulićev trg 9a, HR-10000 Zagreb, Croatia (e-mail: [email protected]) Sandev, D., Mihelj, D. & Kovačić, S.: Plethora of plants – collections of the Botanical Garden, Faculty of Science, University of Zagreb (2): Glasshouse succulents. Nat. Croat. Vol. 27, No. 2, 407- 420*, 2018, Zagreb. In this paper, the plant lists of glasshouse succulents grown in the Botanical Garden from 1895 to 2017 are studied. Synonymy, nomenclature and origin of plant material were sorted. The lists of species grown in the last 122 years are constructed in such a way as to show that throughout that period at least 1423 taxa of succulent plants from 254 genera and 17 families inhabited the Garden’s cold glass- house collection. Key words: Zagreb Botanical Garden, Faculty of Science, historic plant collections, succulent col- lection Sandev, D., Mihelj, D. & Kovačić, S.: Obilje bilja – zbirke Botaničkoga vrta Prirodoslovno- matematičkog fakulteta Sveučilišta u Zagrebu (2): Stakleničke mesnatice. Nat. Croat. Vol. 27, No. 2, 407-420*, 2018, Zagreb. U ovom članku sastavljeni su popisi stakleničkih mesnatica uzgajanih u Botaničkom vrtu zagrebačkog Prirodoslovno-matematičkog fakulteta između 1895. i 2017. Uređena je sinonimka i no- menklatura te istraženo podrijetlo biljnog materijala. Rezultati pokazuju kako je tijekom 122 godine kroz zbirku mesnatica hladnog staklenika prošlo najmanje 1423 svojti iz 254 rodova i 17 porodica. -

South American Cacti in Time and Space: Studies on the Diversification of the Tribe Cereeae, with Particular Focus on Subtribe Trichocereinae (Cactaceae)

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2013 South American Cacti in time and space: studies on the diversification of the tribe Cereeae, with particular focus on subtribe Trichocereinae (Cactaceae) Lendel, Anita Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-93287 Dissertation Published Version Originally published at: Lendel, Anita. South American Cacti in time and space: studies on the diversification of the tribe Cereeae, with particular focus on subtribe Trichocereinae (Cactaceae). 2013, University of Zurich, Faculty of Science. South American Cacti in Time and Space: Studies on the Diversification of the Tribe Cereeae, with Particular Focus on Subtribe Trichocereinae (Cactaceae) _________________________________________________________________________________ Dissertation zur Erlangung der naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorwürde (Dr.sc.nat.) vorgelegt der Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Zürich von Anita Lendel aus Kroatien Promotionskomitee: Prof. Dr. H. Peter Linder (Vorsitz) PD. Dr. Reto Nyffeler Prof. Dr. Elena Conti Zürich, 2013 Table of Contents Acknowledgments 1 Introduction 3 Chapter 1. Phylogenetics and taxonomy of the tribe Cereeae s.l., with particular focus 15 on the subtribe Trichocereinae (Cactaceae – Cactoideae) Chapter 2. Floral evolution in the South American tribe Cereeae s.l. (Cactaceae: 53 Cactoideae): Pollination syndromes in a comparative phylogenetic context Chapter 3. Contemporaneous and recent radiations of the world’s major succulent 86 plant lineages Chapter 4. Tackling the molecular dating paradox: underestimated pitfalls and best 121 strategies when fossils are scarce Outlook and Future Research 207 Curriculum Vitae 209 Summary 211 Zusammenfassung 213 Acknowledgments I really believe that no one can go through the process of doing a PhD and come out without being changed at a very profound level. -

Cactaceae) Revista Peruana De Biología, Vol

Revista Peruana de Biología ISSN: 1561-0837 [email protected] Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos Perú Loaiza S., Christian R.; Roque Gamarra, José Revalidación taxonómica y distribución potencial de Armatocereus brevispinus Madsen (Cactaceae) Revista Peruana de Biología, vol. 23, núm. 1, abril, 2016, pp. 35-41 Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos Lima, Perú Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=195045766004 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Revista peruana de biología 23(1): 035 - 041 (2016) ISSN-L 1561-0837 Revalidación taxonómica y distribución potencial de ARM ATOCEREUS BREVISPINUS doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15381/rpb.v23i1.11831 Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas UNMSM TRABAJOS ORIGINALES Revalidación taxonómica y distribución potencial de Armatocereus brevispinus Madsen (Cactaceae) Taxonomic revalidation and potential distribution of Armatocereus brevispinus Madsen (Cactaceae) Christian R. Loaiza S.1* y José Roque Gamarra2 1 Departamento de Mastozoología, Museo de Historia Natural, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Av. Arenales 1256, Jesús María, Lima, Perú. 2 Laboratorio de Florística, Museo de Historia Natural, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Av. Arenales 1256, Jesús María, Lima, Perú. *Autor para correspondencia Email Christian Loaiza: [email protected] Email José Roque: [email protected] ORCID José Roque: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6840-6603 Resumen Se reporta el primer registro confirmado para el norte de Perú de Armatocereus brevispinus Madsen, una especie de cactácea considerada como endémica de la provincia de Loja, en la región sur del Ecuador. -

Phylogenetic Relationships in the Cactus Family (Cactaceae) Based on Evidence from Trnk/Matk and Trnl-Trnf Sequences

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: http://www.researchgate.net/publication/51215925 Phylogenetic relationships in the cactus family (Cactaceae) based on evidence from trnK/matK and trnL-trnF sequences ARTICLE in AMERICAN JOURNAL OF BOTANY · FEBRUARY 2002 Impact Factor: 2.46 · DOI: 10.3732/ajb.89.2.312 · Source: PubMed CITATIONS DOWNLOADS VIEWS 115 180 188 1 AUTHOR: Reto Nyffeler University of Zurich 31 PUBLICATIONS 712 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Available from: Reto Nyffeler Retrieved on: 15 September 2015 American Journal of Botany 89(2): 312±326. 2002. PHYLOGENETIC RELATIONSHIPS IN THE CACTUS FAMILY (CACTACEAE) BASED ON EVIDENCE FROM TRNK/ MATK AND TRNL-TRNF SEQUENCES1 RETO NYFFELER2 Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University Herbaria, 22 Divinity Avenue, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 USA Cacti are a large and diverse group of stem succulents predominantly occurring in warm and arid North and South America. Chloroplast DNA sequences of the trnK intron, including the matK gene, were sequenced for 70 ingroup taxa and two outgroups from the Portulacaceae. In order to improve resolution in three major groups of Cactoideae, trnL-trnF sequences from members of these clades were added to a combined analysis. The three exemplars of Pereskia did not form a monophyletic group but a basal grade. The well-supported subfamilies Cactoideae and Opuntioideae and the genus Maihuenia formed a weakly supported clade sister to Pereskia. The parsimony analysis supported a sister group relationship of Maihuenia and Opuntioideae, although the likelihood analysis did not. Blossfeldia, a monotypic genus of morphologically modi®ed and ecologically specialized cacti, was identi®ed as the sister group to all other Cactoideae. -

Connoisseurs' Cacti

ThCe actus Explorer The first free on-line Journal for Cactus and Succulent Enthusiasts 1 In the shadow of Illumani 2 Matucana aurantiaca Number 19 3 Cylindropuntia ×anasaziensis ISSN 2048-0482 4 Opuntia orbiculata September 2017 5 Arthrocereus hybrids The Cactus Explorer ISSN 2048-0482 Number 19 September 2017 IN THIS EDITION Regular Features Articles Introduction 3 Matucana aurantiaca 17 News and Events 4 Travel with the Cactus Expert (18) 21 In the Glasshouse 8 Cylindropuntia ×anasajiensis 25 Recent New Descriptions 10 What about Opuntia orbiculata? 30 On-line Journals 12 In the shadow of Illumani 34 The Love of Books 15 Society Pages 51 Plants and Seeds for Sale 55 Books for Sale 62 Cover Picture: Oreocereus pseudofossulatus flowering in Bolivia. See Martin Lowry’s article on Page 34 about his exploration in the shadow of Illumani. Photograph by Martin Lowry. The No.1 source for on-line information about cacti and succulents is http://www.cactus-mall.com The best on-line library of succulent literature can be found at: https://www.cactuspro.com/biblio/en:accueil Invitation to Contributors Please consider the Cactus Explorer as the place to publish your articles. We welcome contributions for any of the regular features or a longer article with pictures on any aspect of cacti and succulents. The editorial team is happy to help you with preparing your work. Please send your submissions as plain text in a ‘Word’ document together with jpeg or tiff images with the maximum resolution available. A major advantage of this on-line format is the possibility of publishing contributions quickly and any issue is never full! We aim to publish your article quickly and the copy deadline is just a few days before the publication date. -

Cacti, Biology and Uses

CACTI CACTI BIOLOGY AND USES Edited by Park S. Nobel UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles London University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 2002 by the Regents of the University of California Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cacti: biology and uses / Park S. Nobel, editor. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ). ISBN 0-520-23157-0 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Cactus. 2. Cactus—Utilization. I. Nobel, Park S. qk495.c11 c185 2002 583'.56—dc21 2001005014 Manufactured in the United States of America 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 01 10 987654 321 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48–1992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper). CONTENTS List of Contributors . vii Preface . ix 1. Evolution and Systematics Robert S. Wallace and Arthur C. Gibson . 1 2. Shoot Anatomy and Morphology Teresa Terrazas Salgado and James D. Mauseth . 23 3. Root Structure and Function Joseph G. Dubrovsky and Gretchen B. North . 41 4. Environmental Biology Park S. Nobel and Edward G. Bobich . 57 5. Reproductive Biology Eulogio Pimienta-Barrios and Rafael F. del Castillo . 75 6. Population and Community Ecology Alfonso Valiente-Banuet and Héctor Godínez-Alvarez . 91 7. Consumption of Platyopuntias by Wild Vertebrates Eric Mellink and Mónica E. Riojas-López . 109 8. Biodiversity and Conservation Thomas H. Boyle and Edward F. Anderson . 125 9. Mesoamerican Domestication and Diffusion Alejandro Casas and Giuseppe Barbera . 143 10. Cactus Pear Fruit Production Paolo Inglese, Filadelfio Basile, and Mario Schirra . -

Classification and Description of World Formation Types

CLASSIFICATION AND DESCRIPTION OF WORLD FORMATION TYPES PART II. DESCRIPTION OF WORLD FORMATIONS (v 2.0) Hierarchy Revisions Working Group (Federal Geographic Data Committee) 2012 Don Faber-Langendoen, Todd Keeler-Wolf, Del Meidinger, Carmen Josse, Alan Weakley, Dave Tart, Gonzalo Navarro, Bruce Hoagland, Serguei Ponomarenko, Jean-Pierre Saucier, Gene Fults, Eileen Helmer This document is being developed for the U.S. National Vegetation Classification, the International Vegetation Classification, and other national and international vegetation classifications. July 18, 2012 This report was produced by NVC partners (NatureServe, Ecological Society of America, U.S. federal agencies) through the Federal Geographic Data Committee. Printed from NatureServe Biotics on 24 Jul 2012 Citation: Faber-Langendoen, D., T. Keeler-Wolf, D. Meidinger, C. Josse, A. Weakley, D. Tart, G. Navarro, B. Hoagland, S. Ponomarenko, J.-P. Saucier, G. Fults, E. Helmer. 2012. Classification and description of world formation types. Part I (Introduction) and Part II (Description of formation types, v2.0). Hierarchy Revisions Working Group, Federal Geographic Data Committee, FGDC Secretariat, U.S. Geological Survey. Reston, VA, and NatureServe, Arlington, VA. i Classification and Description of World Formation Types. Part II: Formation Descriptions, v2.0 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The work produced here was supported by the U.S. National Vegetation Classification partnership between U.S. federal agencies, the Ecological Society of America, and NatureServe staff, working through the Federal Geographic Data Committee (FGDC) Vegetation Subcommittee. FGDC sponsored the mandate of the Hierarchy Revisions Working Group, which included incorporating international expertise into the process. For that reason, this product represents a collaboration of national and international vegetation ecologists. -

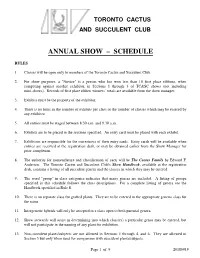

Annual Show – Schedule

TORONTO CACTUS AND SUCCULENT CLUB ANNUAL SHOW – SCHEDULE RULES 1. Classes will be open only to members of the Toronto Cactus and Succulent Club. 2. For show purposes, a "Novice" is a person who has won less than 10 first place ribbons, when competing against another exhibitor, in Sections 1 through 3 of TC&SC shows (not including mini-shows). Records of first place ribbon winners’ totals are available from the show manager. 3. Exhibits must be the property of the exhibitor. 4. There is no limit in the number of exhibits per class or the number of classes which may be entered by any exhibitor. 5. All entries must be staged between 8:30 a.m. and 9:30 a.m. 6. Exhibits are to be placed in the sections specified. An entry card must be placed with each exhibit. 7. Exhibitors are responsible for the correctness of their entry cards. Entry cards will be available when entries are received at the registration desk, or may be obtained earlier from the Show Manager for prior completion. 8. The authority for nomenclature and classification of cacti will be The Cactus Family by Edward F. Anderson. The Toronto Cactus and Succulent Club's Show Handbook , available at the registration desk, contains a listing of all succulent genera and the classes in which they may be entered. 9. The word "group" in class categories indicates that many genera are included. A listing of groups specified in this schedule follows the class descriptions. For a complete listing of genera see the Handbook specified in Rule 8. -

Cleistocactus Crassicaulis West of Palos Blancos Photo

TTHHEE CCHHIILLEEAANNSS 22000044 VOLUME 19 NUMBER 62 Cleistocactus crassicaulis West of Palos Blancos Photo. - F. Vandenbroeck Eulychnia ritteri near Chala Photos: J. Arnold 49 NOT FINDING EULYCHNIA RITTERI From F.Vandenbroeck I am intrigued by the reported occurrence of Eulychnia ritteri near Chala, on the southern coast of Peru. Ritter states in Vol.4 of his work on the cacti of South America, that he only found a very small population of this species which he considers to be a relict of the genus, having become isolated from the remaining populations of Eulychnia which are to be found within the territory of Chile. When we were in Chala we were on the lookout for these plants, but could not find a single trace of them. It would be interesting to know whether this species is still alive in nature in our days. They were found by Ritter in 1954 which is almost half a century ago. Much may have happened in the meantime. Unfortunately Ritter gives no details as to the locality of this population. As far as I know, no one else has ever made any mention of rediscovering these plants - or am I mistaken? .....from F.Ritter, Kakteen in Südamerika Eulychnia ritteri. Tree or bush of 2 to 4 m in height, branching from close to and not far above ground level. ... Flower appearing from anywhere between the middle of the stem to the crown, on all sides of the stem, opening by day and closing by night; petals pink. Type locality - Chala. Discovered July 1954. .....from A.F.H.Buining. -

Presenting Plants for Show—Information for Exhibitors

CACTUS and SUCCULENT SOCIETY of NEW MEXICO P.O. Box 21357 Albuquerque, New Mexico 87154-1357 http://www.new-mexico.cactus-society.org PRESENTING PLANTS FOR SHOW—INFORMATION FOR EXHIBITORS It is perhaps a good idea to first point out some of the benefits to all concerned of entering plants in the Society’s shows. The show is an educational effort by the club for the public, which allows them to see beautiful plants that are new to them, to learn something about the types of succulents that exist, and to find out how they should look when properly cared for. It is useful to the Society in the acquisition of new members, the education of recent members, and the study and display of the plants for all members. Then, it is useful for the entrant to learn how the results of his/her cultivation methods compare to those of others, to learn the names and near relatives of his/her plants, and to show off the results of his/her work, as well as to participate in the above-mentioned educational efforts. Finally, it is good for the plants. As usual, first-, second-, and third-place ribbons will be awarded in each category or subcategory (as decided by the judges), as well as honorable mention ribbons, as deemed appropriate. However, additionally the judges will determine the best of designated plant categories for rosette awards, as well as a Sweepstakes Award (see page 2). Some helpful hints to exhibitors are: Plants should be in good condition: not etiolated (growing too fast toward the light), badly scarred or sunburned, or malformed because of improper cultural conditions. -

Trichocereus.Net Seed List May 2017

Trichocereus.net Seed List May 2017 Trichocereus Growers Worldwide http://facebook.com/groups/trichocereus Instagram: http://Instagram.com/Trichocereus_net Trichocereus Page: http://facebook.com/trichocereus 1 Trichocereus.net Premium Seeds List / Samenliste May 2017 I only stock high quality premium seeds with great germination rates. Because of that, my prices are a little bit more expensive, but I think it´s way better to get 30 super healthy seedlings from a 3 Euro bag than 20 sickly seedlings from a 1000 seeds back of inferior quality. I guarantee viable seeds, no matter what. If one of my types should make problems and not come up due to whatever reasons, you can always send me a message and I´ll send you a new one. The standard price for one bag is 3.00 Euros and the worldwide shipping costs are 3.50 Euros as a registered letter. If you have questions, don´t hesitate to write me to [email protected]! This address is also my Paypal address. You can also send the payment directly at my paypal website http://paypal.me/Trichocereus I ship worldwide and the worldwide shipping costs are always the same 3.50 Euro. I have years of experience shipping to Australia and I label all seeds according to the AQUIS requirements. Most cacti that I have on my list can be imported to Australia (Trichocereus) without problems. But there are a few genera that are considered invasive (eg Opuntia, Haageocereus) and which can´t be shipped there. Please check the AQUIS database called ICON if you are unsure about permitted species.