Threatened Species Nomination Form

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Diurnal Raptors and Airports

Australian diurnal raptors and airports Photo: John Barkla, BirdLife Australia William Steele Australasian Raptor Association BirdLife Australia Australian Aviation Wildlife Hazard Group Forum Brisbane, 25 July 2013 So what is a raptor? Small to very large birds of prey. Diurnal, predatory or scavenging birds. Sharp, hooked bills and large powerful feet with talons. Order Falconiformes: 27 species on Australian list. Family Falconidae – falcons/ kestrels Family Accipitridae – eagles, hawks, kites, osprey Falcons and kestrels Brown Falcon Black Falcon Grey Falcon Nankeen Kestrel Australian Hobby Peregrine Falcon Falcons and Kestrels – conservation status Common Name EPBC Qld WA SA FFG Vic NSW Tas NT Nankeen Kestrel Brown Falcon Australian Hobby Grey Falcon NT RA Listed CR VUL VUL Black Falcon EN Peregrine Falcon RA Hawks and eagles ‐ Osprey Osprey Hawks and eagles – Endemic hawks Red Goshawk female Hawks and eagles – Sparrowhawks/ goshawks Brown Goshawk Photo: Rik Brown Hawks and eagles – Elanus kites Black‐shouldered Kite Letter‐winged Kite ~ 300 g Hover hunters Rodent specialists LWK can be crepuscular Hawks and eagles ‐ eagles Photo: Herald Sun. Hawks and eagles ‐ eagles Large ‐ • Wedge‐tailed Eagle (~ 4 kg) • Little Eagle (< 1 kg) • White‐bellied Sea‐Eagle (< 4 kg) • Gurney’s Eagle Scavengers of carrion, in addition to hunters Fortunately, mostly solitary although some multiple strikes on aircraft Hawks and eagles –large kites Black Kite Whistling Kite Brahminy Kite Frequently scavenge Large at ~ 600 to 800 g BK and WK flock and so high risk to aircraft Photo: Jill Holdsworth Identification Beruldsen, G (1995) Raptor Identification. Privately published by author, Kenmore Hills, Queensland, pp. 18‐19, 26‐27, 36‐37. -

Download This PDF File

3.79 31 Field Notes on the Black Falcon By GEORGE W. BEDGGOOD, Lindenow South, Victoria, 3866. Because of the dearth of published records for Falco subniger in Victoria and southern New South Wales, I have summarised all my observations from 1955 to 1978. Wheeler ( 1967) lists it as "rather rare" but records it for all districts of Victoria. Although a bird of the drier inland plains, its nomadic wanderings may result in unexpected appearances outside its normal range. Factors affecting a regular food supply, such as drought, no doubt are responsible for such movements. Because its non-hunting flight is so "crow-like" it could easily be mistaken as "a corvid". The dark sooty-brown plumage which appears black, particularly when the bird is some distance from the observer, or when seen in silhouette, its similar size and general outline could all contribute to mistaken identification. When hunting, its flight is typically falcon-like, swift and calculated. Due to its size and lack of pattern in the plumage it ought not be confused with any other falcon. Between September 1955 and December 1956 I was able to record the species at Jindera, N.S.W., and in Victoria at Bonegilla and Corryong. The Jindera bird was my first experience with the Black Falcon. A farmer travelling in the car and knowing my interest in birds remarked that a pair had been seen frequently in the district. Approaching Jindera we flushed a bird from a telephone post. The farmer immediately identified it as a Black Falcon. It flapped and glided to a windbreak some distance away, its flight no different to that of the many corvids we had passed since leaving Albury. -

Raptor Nest Survey Summary Report

Raptor Nest Survey Summary Report Lot 5 UBC South Campus January 6, 2020 Submitted to: Polygon Homes Ltd. Raptor Nest Survey Summary Report 1.0 Introduction 1.1 Project Background Diamond Head Consulting Ltd. (DHC) was retained to conduct a raptor nest survey for the proposed development of Lot 5 into a parkade at the University of British Columbia (UBC) South Campus. The development requires the removal of all trees from an existing natural area. As part of this project, on‐ site tree planting is planned upon completion of the parkade. A nest survey is required prior to construction activity to ensure compliance with the federal Migratory Birds Convention Act [1994] and attendant Migratory Birds Regulation [1994] that protects migratory birds, their eggs, and nests. Also, Section 34(a), (b), and (c) of the provincial Wildlife Act [1996 chap 488] prohibits the taking of birds, eggs, and nests. Nests of eagle, peregrine falcon, gyrfalcon, osprey, heron, and burrowing owl are specifically protected whether or not they are active. 1.2 Site Description The project site is a second growth forested area south of W 16th Ave and east of SW Marine Dr, on the corner of Berton Ave and Binning Rd within the UBC South Campus (Figure 1). The nest survey was conducted within the project site and in the forested area immediately adjacent to the north and east. Figure 1 – Project location, UBC South Campus Lot 5, Vancouver, B.C. 3559 Commercial Street, Vancouver B.C. V5N 4E8 | T 604‐733‐4886 1 Raptor Nest Survey Summary Report The project site and adjacent natural areas are a native second growth forest stand mainly consisting of Western Red Cedar (Thuja plicata), Western Hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla), Douglas Fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), and Bigleaf Maple (Acer macrophyllum). -

RSPB CENTRE for CONSERVATION SCIENCE RSPB CENTRE for CONSERVATION SCIENCE Where Science Comes to Life

RSPB CENTRE FOR CONSERVATION SCIENCE RSPB CENTRE FOR CONSERVATION SCIENCE Where science comes to life Contents Knowing 2 Introducing the RSPB Centre for Conservation Science and an explanation of how and why the RSPB does science. A decade of science at the RSPB 9 A selection of ten case studies of great science from the RSPB over the last decade: 01 Species monitoring and the State of Nature 02 Farmland biodiversity and wildlife-friendly farming schemes 03 Conservation science in the uplands 04 Pinewood ecology and management 05 Predation and lowland breeding wading birds 06 Persecution of raptors 07 Seabird tracking 08 Saving the critically endangered sociable lapwing 09 Saving South Asia's vultures from extinction 10 RSPB science supports global site-based conservation Spotlight on our experts 51 Meet some of the team and find out what it is like to be a conservation scientist at the RSPB. Funding and partnerships 63 List of funders, partners and PhD students whom we have worked with over the last decade. Chris Gomersall (rspb-images.com) Conservation rooted in know ledge Introduction from Dr David W. Gibbons Welcome to the RSPB Centre for Conservation The Centre does not have a single, physical Head of RSPB Centre for Conservation Science Science. This new initiative, launched in location. Our scientists will continue to work from February 2014, will showcase, promote and a range of RSPB’s addresses, be that at our UK build the RSPB’s scientific programme, helping HQ in Sandy, at RSPB Scotland’s HQ in Edinburgh, us to discover solutions to 21st century or at a range of other addresses in the UK and conservation problems. -

Australia South Australian Outback 8Th June to 23Rd June 2021 (13 Days)

Australia South Australian Outback 8th June to 23rd June 2021 (13 days) Splendid Fairywren by Dennis Braddy RBL South Australian Outback Itinerary 2 Nowhere is Australia’s vast Outback country more varied, prolific and accessible than in the south of the country. Beginning and ending in Adelaide, we’ll traverse the region’s superb network of national parks and reserves before venturing along the remote, endemic-rich and legendary Strzelecki and Birdsville Tracks in search of a wealth of Australia’s most spectacular, specialised and enigmatic endemics such as Grey and Black Falcons, Letter-winged Kite, Black-breasted Buzzard, Chestnut- breasted and Banded Whiteface, Gibberbird, Yellow, Crimson and Orange Chats, Inland Dotterel, Flock Bronzewing, spectacular Scarlet-chested and Regent Parrots, Copperback and Cinnamon Quail- thrushes, Banded Stilt, White-browed Treecreeper, Red-lored and Gilbert’s Whistlers, an incredible array of range-restricted Grasswrens, the rare and nomadic Black and Pied Honeyeaters, Black-eared Cuckoo and the incredible Major Mitchell’s Cockatoo. THE TOUR AT A GLANCE… THE SOUTH AUTRALIAN OUTBACK ITINERARY Day 1 Arrival in Adelaide Day 2 Adelaide to Berri Days 3 & 4 Glue Pot Reserve and Calperum Station Day 5 Berri to Wilpena Pound and Flinders Ranges National Park Day 6 Wilpena Pound to Lyndhurst Day 7 Strzelecki Track Day 8 Lyndhurst to Mungerranie via Marree and Birdsville Track Day 9 Mungerranie and Birdsville Track area Day 10 Mungerranie to Port Augusta Day 11 Port Augusta area Day 12 Port Augusta to Adelaide Day 13 Adelaide and depart RBL South Australian Outback Itinerary 3 TOUR MAP… RBL South Australian Outback Itinerary 4 THE TOUR IN DETAIL… Day 1. -

Codistributed Lineages of Feather Lice Show

CODISTRIBUTED LINEAGES OF FEATHER LICE SHOW DIFFERENT PHYLOGENETIC PATTERNS A Dissertation by THERESE ANNE CATANACH Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Nova J. Silvy Co-Chair of Committee, Robert A. McCleery Committee Members, Jessica E. Light Julio Bernal Head of Department, Michael P. Masser August 2017 Major Subject: Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences Copyright 2017 Therese A. Catanach ABSTRACT Recent molecular phylogenies have suggested that hawks (Accipitridae) and falcons (Falconidae) form 2 distantly related groups within birds. Avian feather lice have often been used as a model for comparing host and parasite phylogenies, and in some cases there is significant congruence between them. Using 1 mitochondrial and 3 nuclear genes, I inferred a phylogeny for the feather louse genus Degeeriella (which are all obligate raptor ectoparasites) and related genera. This phylogeny indicated that Degeeriella is polyphyletic, with lice from falcons and hawks forming 2 distinct clades. Falcon lice were sister to lice from African woodpeckers, while Capraiella, a genus of lice from rollers lice, was embedded within Degeeriella from hawks. This phylogeny showed significant geographic structure, with host geography playing a larger role than host taxonomy in explaining louse phylogeny, particularly within clades of closely related lice. However, the louse phylogeny broadly reflects host phylogeny, for example Accipiter lice form a distinct clade. Unlike most bird species, individual kingfisher species (Aves: Alcidae) are typically parasitized by 1 of 3 genera of lice (Insecta: Phthiraptera). These lice partition hosts by subfamily: Alcedoecus and Emersoniella parasitize Daceloninae whereas Alcedoffula parasitizes both Alcedininae and Cerylinae. -

Fish and Wildlife Service Raptor Fact Sheet (Pdf)

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Raptors Diurnal and Nocturnal Birds of Prey What Is a Raptor? Many long-distance migrants, such as A raptor is a bird of prey that is known for Swainsons and Broad-winged hawks, have its predatory habits of feeding on other experienced declines due to habitat animals. This group of birds possesses destruction and hazards such as pesticide several unique anatomical characteristics use in their wintering grounds. Swainsons that allow them to be superior hunters. Hawks breed in the western and These include excellent sensory abilities midwestern U.S. and Canada and migrate such as binocular vision and keen hearing in all the way to central Argentina for the Migratory Bird Management order to detect prey, large powerful winter. Conditions on the migratory route grasping feet with razor-sharp talons for as well as in the wintering countries have catching prey, and generally large, hooked had a major impact on their populations Mission bills that can tear prey. There are 30 returning to the U.S. each year. species of hawks, falcons, and eagles, as To conserve migratory bird well as 18 species of owls breeding in North Many grassland raptor species, including populations and their habitats America. In this large group of birds, Ferruginous Hawk, Swainsons Hawk, Northern Harrier, Golden Eagle, and for future generations, through there are diurnal, or daytime, species, such as hawks, falcons, and eagles, and Burrowing Owl, have sharply declined in careful monitoring and effective nocturnal, or nighttime, species, such as many locations over the past few decades management. owls. -

THE PEREGRINE FALCON &Lpar;<I>Falco Peregrinus

RAPTOR RESEARCH A QUARTERLY PUBLICATON OF THE RAPTOR RESEARCHFOUNDATION, INC. VOL. 18 FALL 1984 NO. 3 THE PEREGRINE FALCON (Falcoperegrinus macropus) Swainson IN SOUTHEASTERN QUEENSLAND G. V. CZECHURA ABSTRACT- Most studies of PeregrineFalcon (Falco peregrinus) biology have been conducted in Europeand North America(Hickey and Anderson1969; Ratcliffe 1980; Gade 1982). Informationconcerning southern hemisphere Peregrinesis restrictedto the studiesof Glunie(1972, 1976) on Fiji, reviewsby Gade(1969), Brown (1970) and Steyn (1982)of African populations,while Chaffer (1944),Jones and Bren (1978), Norriset al. (1977), Olsenand Olsen(1979), Olsenet al. (1979),Olsen (1982), Pruett-Jones et al. (1981a, b), Walsh(1978) and White et al. (1981)provide important contributions for Australia. Declines in some nothern hemisphere popula- mediatevicinity of the regionalboundary (Broad- tions due to the effectsof pesticides(Hickey 1969; bent 1889; Barnard and Barnard 1925; Longmore Bijleveld1974; Newton 1979;Ratcliffe 1980; Cade 1978; Passmore1982). Vegetationtype appearsto 1982) have served to focus considerable attention exert little or no influence on the overall distribu- onthe distribution •nd dynamics ofregional Pereg- tion here, as closed-forests,open-forests, wood- rine Falcon(Falco peregrinus) populations. Concern lands,wetlands and agriculturalareas are all fre- has been expressedabout the potential affectsof quented by falcons.For example, Dwyer et al. pesticideson populationsof this falconwithin Au- (1979) recorded peregrinesfrom 8 of 12 habitat stralia(Olsen and Olsen1979, 1981; Pruett-Joneset typesfound acrossCooloola. The vegetationtypes al. 1981b). Existingstudies on the statusof the representedhere included vine forest, various peregrinewithin Australiahave been conducted in formsof openforest and woodland as well as heath, the southeastern corner of the continent (Olsen and herb and sedgeland.Wide occupationof vegetation Olsen in press)and little is known of the statusof typeshas been noted also in the Rockhamptonarea northern and westernpopulations. -

Learning About BUSH Stone-Curlews

© 2018 Nature Conservation Working Group. This publication has been prepared as a resource for schools. Schools may copy, distribute and otherwise freely deal with this publication, or any part of it, for any educational purpose, provided that Nature Conservation Working Group is attributed as the owner. Acknowledgements: Jan Lubke and Judy Frankenberg from the Nature Conservation Working Group, Elisa Tack from Murray Local Land Services, Owen Dunlop from Petaurus Education Group Inc. and Val White. This resource was funded by Nature Conservation Working Group and supported by Murray Local Land Services through funding from NSW Catchment Action. Author: Peter Coleman, PeeKdesigns Photographers: Jan Lubke, Chris Tzaros (front cover), Raoul Slater, Simon Dallinger, Kelly Coleman, Thomas Brown, Darren Marshall Design: PeeKdesigns www.peekdesigns.com.au Printed on 100% recycled and uncoated stock. by Peter Coleman LeARnInG ABOUt BUSH StOne-CURLeWS CONTENTS Introduction for teachers ........................................................2 What are Bush Stone-curlews? ...................................................6 Activity: Colouring the Curlew . 7 Weir-loo ....................................................................9 Activity: Did you hear that? . 10 Activity: Grouping similar things . 11 Classification ................................................................12 Activity: Find the key to the name . 13 Activity: Making an Origami Curl . 14 Habitat ....................................................................16 Activity: -

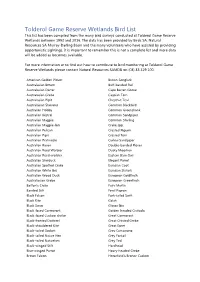

Tolderol Game Reserve Wetlands Bird List This List Has Been Compiled from the Many Bird Surveys Conducted at Tolderol Game Reserve Wetlands Between 1993 and 2016

Tolderol Game Reserve Wetlands Bird List This list has been compiled from the many bird surveys conducted at Tolderol Game Reserve Wetlands between 1993 and 2016. The data has been provided by Birds SA, Natural Resources SA Murray-Darling Basin and the many volunteers who have assisted by providing opportunistic sightings. It is important to remember this is not a complete list and more data will be added as becomes available. For more information or to find out how to contribute to bird monitoring at Tolderol Game Reserve Wetlands please contact Natural Resources SAMDB on (08) 85 329 100. American Golden Plover Brown Songlark Australasian Bittern Buff-banded Rail Australasian Darter Cape Barren Goose Australasian Grebe Caspian Tern Australasian Pipit Chestnut Teal Australasian Shoveler Common Blackbird Australian Hobby Common Greenshank Australian Kestrel Common Sandpiper Australian Magpie Common Starling Australian Magpie-lark Crake spp. Australian Pelican Crested Pigeon Australian Pipit Crested Tern Australian Pratincole Curlew Sandpiper Australian Raven Double-banded Plover Australian Reed Warbler Dusky Moorhen Australian Reed-warbler Eastern Barn Owl Australian Shelduck Elegant Parrot Australian Spotted Crake Eurasian Coot Australian White Ibis Eurasian Skylark Australian Wood Duck European Goldfinch Australiasian Grebe European Greenfinch Baillon's Crake Fairy Martin Banded Stilt Feral Pigeon Black Falcon Fork-tailed Swift Black Kite Galah Black Swan Glossy Ibis Black-faced Cormorant Golden-headed Cisticola Black-faced Cuckoo-shrike -

STATUS and CONSERVATION of RAPTORS in AUSTRALIA&Apos;S

J. RaptorRes. 32 (1) :64-73 ¸ 1998 The Raptor ResearchFoundation, Inc. STATUS AND CONSERVATION OF RAPTORS IN AUSTRALIA' S TROPI CS NICK MOONEY Parksand WildlifeSet'vice, GPO Box 44A, Hobart 7001, Tasmania,Australia ABSTRACT.----•Iof Australia's34 raptorsare found in the tropics.No full speciesand onlyone subspecies, an island endemic owl, are extinct. All of Australia'sthree threatened, diurnal speciesare endemic to the continent. One, the Vulnerable Red Goshawk (Erythrotriochisradiatus), is endemic to Australia's tropical forestsand is under threat from lossof habitat, persecution,and egg collecting.Conservation efforts include legal protection, education, and keeping nest sitessecret. A secondspecies, the rare Square-tailedKite (Lophoictiniaisura) is widelydistributed and, exceptfor clearingof woodland,threats are not obvious.Many raptors from arid areas,including the endemic Grey Falcon (Falcohypoleucos), "winter" in tropicalwoodlands. For adequateconservation, critical habitatsof the Grey Falconmust be identified. Grey Falconsshould be helped in the long term by the anticipatedreduction of rabbitsin arid Australiaby rabbit calicivirusdisease, but widespreadclearing of tropicalwoodlands for agriculture continuesas does local, heavy use of pesticides.Although no speciesof owls are threatened, five sub- speciesare; two are subspeciesof the endemic RufousOwl (Ninox rufa, one rare and one insufficiently known) and two are subspeciesof the Masked Owl (Tyt0 novaehollandiae,both insufficientlyknown). Threats include lossof critical habitat to fire and agriculture.On ChristmasIsland, the smallpopulations of endemicsubspecies of the BrownGoshawk (Accipiterfasciatus) and MoluccanHawk-owl (N. squamipila) are Vulnerable and threatened by loss of habitat to urbanization and formerly mining. Besideslegal protection, conservationefforts have included educationand habitat preservation.The tropicalEastern Grass-owl(T. longimembris)is secure although some populationsare under pressurefrom agriculture (including rodenticides) and urbanization. -

Raptor Conservation in Switzerland – Overview

Raptor Conservation in Switzerland | Overview 1 Sabine Herzog FOEN & Stefan Werner SOI Gypaète barbu. © Roland Clerc Raptor Conservation in Switzerland | Overview 2 Sabine Herzog FOEN & Stefan Werner SOI Federal Department of the Environment, Transport, Energy and Communications DETEC Federal Office for the Environment FOEN Species, Ecosystems, Landscapes Division Raptor Conservation in Switzerland “Overview" MoU Raptor – TAG3 Sempach, 12.12.2018 Basel Zürich Sempach Bern Vienna GenevaSempach Nizza Raptor Conservation in Switzerland | Overview 4 Sabine Herzog FOEN & Stefan Werner SOI Switzerland is divers….. ~46,000 species (potentially 60,000) 49 endemics A gradient from mediterranean to high alpine species 31% Forest (>50% protective forest) 35.9% Agriculture (12% organic) 7.5% «people-habitat» and infrastructure (60% sealed) Raptor Conservation in Switzerland | Overview 5 Sabine Herzog FOEN & Stefan Werner SOI bio-divers… Raptor Conservation in Switzerland | Overview 6 Sabine Herzog FOEN & Stefan Werner SOI Raptor Conservation in Switzerland | Overview 7 Sabine Herzog FOEN & Stefan Werner SOI but also cultural divers Raptor Conservation in Switzerland | Overview 8 Sabine Herzog FOEN & Stefan Werner SOI «First biodiversity crisis» Engadin 1928 Saane 1894 Raptor Conservation in Switzerland | Overview 9 Sabine Herzog FOEN & Stefan Werner SOI First laws on «nature conservation» 1875/76 first forestry law & hunting and bird conservation law > Sustainable forest use & afforestation > Protection of females & offspring > Delimination of protected