Evolving Relationship Between the Buddhist Monastic Order and the Imperial States of Medieval China Mario Poceski*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exkurs 7: Huan Wen Und Yin Hao (S017) Nachdem Das Triumvirat Yu

Alex Angehrn, 9402 Mörschwil, www.sansui-angehrn.ch 20 Exkurs 7: Huan Wen und Yin Hao (S017) Nachdem das Triumvirat Yu Liang, Wang Dao und Chi Jian gestorben war, weitete sich der blutige Kampf zwischen der Wang- und Yu-Familie aus, aber nach Wang Yunzhi's Tod fehlte dem Wang-Clan von Langye die Führungspersönlichkeit, die schwierige politische Lage durch- zustehen. Nachdem Wang Xizhi das Gouverneursamt von Jiangxi und Fujian abgegeben hatte, fiel diese Region in die Hände von Yu Bing 庾冰 (296-344) und zusammen mit Yu Yi dominierte der Yu-Clan mit seinem Einfluss die Nation. Yu Yi bestimmte 345 auf dem Totenbett Yu Yuanzhi 庾爰之 (ca. 325-360) als Nachfolger. Ministerpräsident He Chong zog jedoch Huan Wen für das Amt vor, um den immer mächtiger werdenden Yu-Clan, einzudämmen. Huan Wen hegte von jung auf grandiose Pläne und war genial in der Zivilregierung. 346 forderte er von der Regierung die Einwilligung zum Angriff gegen Sichuan und befahl ohne Einwilligung der Regierung eigenmächtig die Entsendung von Truppen. Im Jahr 347 vernichtete Huan Wen in kurzer Zeit das Land Cheng-Han und verleibte die gesamte Provinz Sichuan der östlichen Jin ein. Die Regierung machte Huan Wen zum General der Westprovinzen und seine Macht erstreckte sich nun weit über den Staat. Der schwache Kaiser Mudi 穆帝 (343-361) traute sich nicht, Huan Wen entgegenzutreten. Aber Ministerpräsident Sima Yu ernannte absichtlich dessen Rivalen Yin Hao zum Gouverneur von Yangzhou. Yin Hao hatte unter Yu Liang zusammen mit Wang Xizhi als Stabsoffizier gedient, führte später ein zurückgezogenes Leben und lehnte lange Anfragen für den Beamtendienst ab. -

The Final Chapter of This Thesis Is a Case Study of the Late Twelfth to Early Thirteenth Century Court Artist Turned Eccentric Painter Liang Kai 梁楷

CHAPTER SIX LIANG KAI: INCARNATIONS OF A MASTER The final chapter of this thesis is a case study of the late twelfth to early thirteenth century court artist turned eccentric painter Liang Kai 梁楷. Following the preceding chapters’ examinations of the agency of narrative themes and clerical inscription in the reception of Chan figure paintings, the ensuing analysis explores the agency of the ideal of the artist. Liang has come to embody two distinctive ideals. One is of Liang as an expressive and eccentric creator of Chan images, depicting wild and heterodox subjects in brush modes that challenged accepted conventions of painting practice. Extant works of this type are, for the most part, preserved in Japanese collections (figs. 6.1-6.2).422 The second Liang Kai is a master of careful and meticulous depiction, who was admired by his court painter contemporaries for his ‘exquisite brush’ (Chinese: jingmei zhi bi 精美之筆).423 The majority of Liang Kai’s attributions that embody this ideal have been preserved through Chinese collections (fig. 6.3).424 This chapter problematises Liang Kai’s dichotomous reception as either an eccentric drunken genius, or a superlative court draughtsman, through the critical examination of his historic reception in both China and Japan. The ensuing discussion will illustrate the construction and augmentation of Liang’s distinctive images in his Chinese and Japanese transmissions, based on analyses of extant works attributed to Liang Kai, and of historic texts on Liang’s artistic practice and oeuvre. This approach aims to reveal the complex overlap and interplay of Liang’s supposedly distinctive cursive and meticulous modes of brushwork. -

Four Sichuan Buddhist Steles and the Beginnings of Pure Land Imagery in China Author(S): Dorothy C

Four Sichuan Buddhist Steles and the Beginnings of Pure Land Imagery in China Author(s): Dorothy C. Wong Source: Archives of Asian Art, Vol. 51 (1998/1999), pp. 56-79 Published by: University of Hawai'i Press for the Asia Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20111283 . Accessed: 22/11/2013 13:42 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of Hawai'i Press and Asia Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Archives of Asian Art. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.143.172.192 on Fri, 22 Nov 2013 13:42:46 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Four Sichuan Buddhist Steles and the Beginnings of Pure Land Imagery in China Dorothy C.Wong University of Virginia 1 he Northern and Southern Dynasties (386?589) iswell thriving economic and cultural center since Han times, a recognized as period of significant developments in but compared with Nanjing and Luoyang, capital cities Chinese art history. Idioms and artistic conventions estab where ritual art in the service of a state ideology remained lished in Han-dynasty (202 BCE?220 CE) art continued, an imperative, Sichuan always allowed artists a much while the acceptance of Buddhism and Buddhist art forms greater degree of freedom. -

Seeing with the Mind's Eye: the Eastern Jin Discourse of Visualization and Imagination Author(S): TIAN XIAOFEI Source: Asia Major , 2005, THIRD SERIES, Vol

Seeing with the Mind's Eye: The Eastern Jin Discourse of Visualization and Imagination Author(s): TIAN XIAOFEI Source: Asia Major , 2005, THIRD SERIES, Vol. 18, No. 2 (2005), pp. 67-102 Published by: Academia Sinica Stable URL: http://www.jstor.com/stable/41649906 JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Academia Sinica is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Asia Major This content downloaded from 206.253.207.235 on Mon, 13 Jul 2020 17:58:56 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms TIAN XIAOFEI Seeing with the Mind's Eye: The Eastern Jin Discourse of Visualization and Imagination This with with paper the thephysical physical world, explores or more world, specifically, a series with or more landscape, of acts dur- specifically, of the mind with in landscape, its interaction dur- ing the intellectually coherent hundred-year period coinciding with the dynasty known as the Eastern Jin (317-420). Chinese landscape poetry and landscape paintings first flourished in the Six Dynasties. Landscape was an essential element in the so-called "poetry of arcane discourse" ( xuanyan shi 3CHHÍ) of the fourth century, a poetry drawing heavily upon the vocabulary and concerns of the Daoist philosophy embodied in Laozi and ZJiuangzi as well as upon Buddhist doctrine; the earliest known record of landscape painting also dates to the Eastern Jin.1 How was landscape perceived by the Eastern Jin elite, and how was this unique mode of perception informed by a complex nexus of contemporary cultural forces? These are the questions to be dealt with in this paper. -

Pure Mind, Pure Land a Brief Study of Modern Chinese Pure Land Thought and Movements

Pure Mind, Pure Land A Brief Study of Modern Chinese Pure Land Thought and Movements Wei, Tao Master of Arts Faculty ofReligious Studies McGill University Montreal, Quebec, Canada July 26, 2007 In Partial Fulfillment ofthe Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Faculty ofReligious Studies of Mc Gill University ©Tao Wei Copyright 2007 All rights reserved. Library and Bibliothèque et 1+1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Bran ch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-51412-2 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-51412-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, électronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

A Distant Mirror. Articulating Indic Ideas in Sixth and Seventh Century

Funayama Toru Chinese Translations of Pratyakṣa pp. 33–61 in: Chen-kuo Lin / Michael Radich (eds.) A Distant Mirror Articulating Indic Ideas in Sixth and Seventh Century Chinese Buddhism Hamburg Buddhist Studies, 3 Hamburg: Hamburg University Press 2014 Imprint Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (German National Library). The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. The online version is available online for free on the website of Hamburg University Press (open access). The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek stores this online publication on its Archive Server. The Archive Server is part of the deposit system for long-term availability of digital publications. Available open access in the Internet at: Hamburg University Press – http://hup.sub.uni-hamburg.de Persistent URL: http://hup.sub.uni-hamburg.de/purl/HamburgUP_HBS03_LinRadich URN: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn/resolver.pl?urn:nbn:de:gbv:18-3-1467 Archive Server of the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek – http://dnb.d-nb.de ISBN 978-3-943423-19-8 (print) ISSN 2190-6769 (print) © 2014 Hamburg University Press, Publishing house of the Hamburg State and University Library Carl von Ossietzky, Germany Printing house: Elbe-Werkstätten GmbH, Hamburg, Germany http://www.elbe-werkstaetten.de/ Cover design: Julia Wrage, Hamburg Contents Foreword 9 Michael Zimmermann Acknowledgements 13 Introduction 15 Michael Radich and Chen-kuo Lin Chinese Translations -

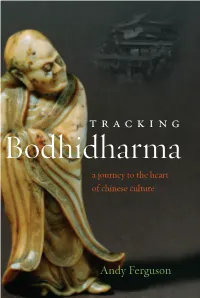

Tracking B Odhidharma

/.0. !.1.22 placing Zen Buddhism within the country’s political landscape, Ferguson presents the Praise for Zen’s Chinese Heritage religion as a counterpoint to other Buddhist sects, a catalyst for some of the most revolu- “ A monumental achievement. This will be central to the reference library B)"34"35%65 , known as the “First Ances- tionary moments in China’s history, and as of Zen students for our generation, and probably for some time after.” tor” of Zen (Chan) brought Zen Buddhism the ancient spiritual core of a country that is —R)9$%: A4:;$! Bodhidharma Tracking from South Asia to China around the year every day becoming more an emblem of the 722 CE, changing the country forever. His modern era. “An indispensable reference. Ferguson has given us an impeccable legendary life lies at the source of China and and very readable translation.”—J)3! D54") L))%4 East Asian’s cultural stream, underpinning the region’s history, legend, and folklore. “Clear and deep, Zen’s Chinese Heritage enriches our understanding Ferguson argues that Bodhidharma’s Zen of Buddhism and Zen.”—J)5! H5<4=5> was more than an important component of China’s cultural “essence,” and that his famous religious movement had immense Excerpt from political importance as well. In Tracking Tracking Bodhidharma Bodhidharma, the author uncovers Bodhi- t r a c k i n g dharma’s ancient trail, recreating it from The local Difang Zhi (historical physical and textual evidence. This nearly records) state that Bodhidharma forgotten path leads Ferguson through established True Victory Temple China’s ancient heart, exposing spiritual here in Tianchang. -

Biographies of Eminent Monks Volume II (DRAFT!!!! – DO NOT CITE!!) Imre Galambos

Biographies of Eminent Monks Volume II (DRAFT!!!! – DO NOT CITE!!) Imre Galambos 1. Kumārajīva Kumārajīva (Jiumoluoshi 鳩摩羅什) means Age of a Child (tongshou 童壽). He was a native of India, and his family for generations served as chief ministers. Kumārajīva’s grandfather Daduo 達多 (Datta?) was an extraordinary person whose name was well known in their country. His father Jiumoyan 鳩摩炎 (Kumārayāna?) was intelligent and had exceptional integrity, and was about to inherit the post of chief minister but instead declined it and became a monk. He went east, crossing the Pamirs.1 Having heard of his abandoning worldly glory, the king of Kucha (Qiuci 龜茲) held him in high esteem. He came in person to the edge of the city to welcome him and to request him to become a state preceptor. The king had a younger sister who had just turned nineteen. Knowledgeable and bright, she could learn anything she read through once, and she could recite by heart anything just by hearing it. She had on her body a red birthmark which foretold that she would give birth to a sage son. Rulers of different countries had requested to marry her but she would not consent to this. But when she saw Kumārayāna, she wished to marry him, and thus [the king] compelled him to marry her. Soon she conceived Kumārajīva. When he was still in his mother’s womb, she sensed that her intuition and capacity for supernatural understanding was twice as strong as what it was normally. She had often heard of the virtue of the great monatery of Queli 雀梨, and that it had monks who had attained the Way. -

A Distant Mirror. Articulating Indic Ideas in Sixth and Seventh Century

Ching Keng A Re-examination of the Relationship between the Awakening of Faith and Dilun School Thought, Focusing on the Works of Huiyuan pp. 183–215 in: Chen-kuo Lin / Michael Radich (eds.) A Distant Mirror Articulating Indic Ideas in Sixth and Seventh Century Chinese Buddhism Hamburg Buddhist Studies, 3 Hamburg: Hamburg University Press 2014 Imprint Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (German National Library). The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. The online version is available online for free on the website of Hamburg University Press (open access). The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek stores this online publication on its Archive Server. The Archive Server is part of the deposit system for long-term availability of digital publications. Available open access in the Internet at: Hamburg University Press – http://hup.sub.uni-hamburg.de Persistent URL: http://hup.sub.uni-hamburg.de/purl/HamburgUP_HBS03_LinRadich URN: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn/resolver.pl?urn:nbn:de:gbv:18-3-1467 Archive Server of the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek – http://dnb.d-nb.de ISBN 978-3-943423-19-8 (print) ISSN 2190-6769 (print) © 2014 Hamburg University Press, Publishing house of the Hamburg State and University Library Carl von Ossietzky, Germany Printing house: Elbe-Werkstätten GmbH, Hamburg, Germany http://www.elbe-werkstaetten.de/ Cover design: Julia Wrage, Hamburg Contents Foreword 9 Michael -

Master Yongjue Yuanxian and the Revival of Chinese Buddhism in 17Th Century Fujian Area

Between The Mundane and Super-Mundane: Master Yongjue Yuanxian and the Revival of Chinese Buddhism in 17th Century Fujian Area Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Glaze, Shyling Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 29/09/2021 02:44:48 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/626639 BETWEEN THE MUNDANE AND SUPER-MUNDANE: MASTER YONGJUE YUANXIAN AND THE REVIVAL OF CHINESE BUDDHISM IN 17TH CENTURY FUJIAN AREA by Shyling Glaze _________________________ Copyright © Shyling Glaze 2017 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2017 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This dissertation has been submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the library. Brief quotations from this dissertation are allowable without special permission, provided that an accurate acknowledgment of the source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his or her judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of the scholarship. -

Development of Gardens in Ancient China, and Pure Land and Pure Land Gardens LU Zhou Professor, Tsinghua University, People’S Republic of CHINA

II LU Zhou Development of Gardens in Ancient China, and Pure Land and Pure Land Gardens LU Zhou Professor, Tsinghua University, People’s Republic of CHINA As one of the oldest groups of gardens in the world, Chinese 1. Chinese gardens in the Han, Wei, and Two Jins gardens date back to the time before the Yin dynasty. After dynasties (the Tung-Chin and 55 Western Chin the Sui and Tang dynasties, Chinese gardens started to show dynasties) a tendency to place emphasis on “Yi Jing,” which eventually The Chinese gardens date back to the time before the Yin became one of the basic features of Chinese gardens. Chinese and Zhou dynasties. Indeed, descriptions about the gardens gardens, which are the main component and embodiment of are found in “Shi-Jing.” Many of the gardens in those days the culture of China, influenced the development of gardens were designed in formats similar to botanical gardens, and in East Asian countries (via Japanese envoys to China during were built for Emperors and feudal lords. Those gardens also the Tang and Sung dynasties), as well as gardens in Europe in had such functions as temporary palaces (used by Emperors the 18th and 19th centuries (via Western missionaries). When on tours), farms, and hunting grounds. These gardens the development process of Chinese gardens is observed, transformed into grand imperial gardens after the Qin and one can find that traditional factors in China, including Han dynasties, but the functions as temporary palaces, philosophy, faith, and religion, are all reflected in theme and farms, and hunting grounds, etc. -

Was Lushan Huiyuan a Pure Land Buddhist? Evidence from His Correspondence with Kumārajīva About Nianfo Practice

Chung-Hwa Buddhist Journal (2008, 21:175-191) Taipei: Chung-Hwa Institute of Buddhist Studies 中華佛學學報第二十一期 頁175-191 (民國九十七年),臺北:中華佛學研究所 ISSN:1017-7132 Was Lushan Huiyuan a Pure Land Buddhist? Evidence from His Correspondence with Kumārajīva About Nianfo Practice Charles B. Jones The Catholic University of America Abstract The Buddhist community in China has traditionally considered Lushan Huiyuan 盧山慧遠 334-416) to be the first “patriarch” (zu 祖) of the Pure Land school, based almost entirely on his having hosted a meeting of monks and scholars in the year 402 to engage in nianfo 念佛 practice and vow rebirth in the Western Paradise of Amitābha. This article examines the extent to which Huiyuan might be considered a “Pure Land Buddhist” by looking at an exchange between him and the great translator Kumārajīva on the topic of Buddha-contemplation, as well as other sources for his life that demonstrate his participation in activities that could be regarded as part of the Pure Land repertoire of ritual and doctrine in the early fifth century. Keywords: Lushan Huiyuan, Pure Land, Kumārajīva, nianfo, Patriarch. 176 • Chung-Hwa Buddhist Journal Volume 21 (2008) 廬山慧遠是淨土信仰者嗎? 以慧遠與鳩摩羅什對念佛修行的書信問答為論據 Charles B. Jones 周文廣 美國天主教大學神學與宗教學院助理教授 提要 在中國佛教傳統上視廬山慧遠是淨土宗的初祖,大部分是基於他在西元 402 年 所舉辦的法會,其中參與的僧眾及學者專修念佛法門及誓願往生西方阿彌陀佛淨土 者。此篇文章藉由考察慧遠與偉大的翻譯家鳩摩羅十對於念佛三昧的交流,以及陳 述其生平的其它出處,也就是對慧遠從事被視為第五世紀早期淨土宗儀式與教法的 部份,檢視其被視為淨土信仰者的程度。 關鍵字:廬山慧遠、淨土、鳩摩羅十、念佛、初祖 Was Lushan Huiyuan a Pure Land Buddhist? • 177 Introduction Early in the year 406 C.E., the eminent Chinese monk Huiyuan of Mount Lu (Lushan Huiyuan 盧山慧遠 334-416) wrote a letter to the Kuchean monk-translator Kumārajīva (Ch: Jiumoloushi 鳩摩羅什), then residing in the northern capital of Chang’an 長安.1 Huiyuan had heard that Kumārajīva was considering leaving China to return west, and so he wanted to write to him on “several tens of” doctrinal matters that continued to perplex him2.