School Desegregation, the Philadelphia Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

©2019 Spencer T. Clayton ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

©2019 Spencer T. Clayton ALL RIGHTS RESERVED TAX ABATEMENTS AND GENTRIFICATION: HOW GOVERNMENT POLICY DISRUPTS COMMUNITIES by SPENCER T. CLAYTON A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Camden Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Public Affairs Written under the direction of Richard A. Harris, Ph.D. And approved by ____________________________________ Richard A. Harris, Ph.D., Committee Chair ____________________________________ Paul Jargowsky, Ph.D. ____________________________________ Lorraine C. Minnite, Ph.D. ____________________________________ Adam Okulicz-Kozaryn, Ph.D. Camden, New Jersey May 2019 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Tax Abatements and Gentrification: How Government Policy Disrupts Communities by SPENCER T. CLAYTON Dissertation Director: Richard A. Harris, Ph.D. Urban municipal governments often face challenges when redeveloping their distressed centers. In 2000, the City Council of Philadelphia passed a series of bills modifying its existing residential tax abatement policies to expand their eligibility and to make them last for ten years. The timing of the passage of these bills also corresponded with Mayor John Street’s Neighborhood Transformation Initiative (NTI), which aimed to prepare land for redevelopment. The combination of the revised abatement policies and NTI created a series of competing interests for politicians, business owners, and community organizations. Utilizing a methodological design consisting a historical critical analysis based on urban regime theory, GIS, and regression analysis, this dissertation profiles the formulation, implementation, and impact of Philadelphia’s tax abatement policies from 2000 to 2010. It also proposes a mechanism by which government policies can facilitate or accelerate gentrification. Results show support for a relationship between the incidence of tax abatements and gentrification. -

Housing Markets and Social Capital: the Role of Participation, Institutions, and Diversity in Neighborhood Transformation

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Culture Builds Community Culture Builds Community Evaluation—1997-2002 6-2001 Housing Markets and Social Capital: The Role of Participation, Institutions, and Diversity in Neighborhood Transformation Mark J. Stern University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/siap_culture_builds_community Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, Social Policy Commons, Sociology Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Stern, Mark J., "Housing Markets and Social Capital: The Role of Participation, Institutions, and Diversity in Neighborhood Transformation" (2001). Culture Builds Community. 14. https://repository.upenn.edu/siap_culture_builds_community/14 The release of the John Street administration’s Neighborhood Transformation Initiative (NTI) in April 2001 marked a bold step by city government and the private sector to address the long-term problems of economic and social decline in the city of Philadelphia. The plan called for a differentiated strategy of public-private partnership with the goal of reinvigorating housing markets throughout the city. According to the NTI housing market analysis, more than four out of five Philadelphians lived in the bottom three market clusters—transitional, distressed, and reclamation. SIAP's Culture Builds Community inquiry was undertaken from 1996 to 2001 with support by the William Penn Foundation. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/siap_culture_builds_community/14 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Housing Markets and Social Capital: The Role of Participation, Institutions, and Diversity in Neighborhood Transformation Abstract This paper examines the housing markets described in the Philadelphia Neighborhood Transformation Initiative (NTI), launched by Mayor John Street in April 2001, through the lens of social capital indicators. -

Community 2019

Southeastern Pennsylvania Community 2019 SOUTHEASTERN PENNSYLVANIA SOUTHEASTERN PENNSYLVANIA HEALTH NEEDS ASSESSMENT Partnering Hospitals • Abington Hospital • Abington Lansdale Hospital • Chester County Hospital • Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia • Einstein Medical Center Montgomery NEEDS ASSESSMENT HEALTH COMMUNITY • Einstein Medical Center Philadelphia • Einstein Medical Center Elkins Park • Grand View Hospital • Holy Redeemer Hospital • Jefferson Bucks Hospital • Jefferson Frankford Hospital • Jefferson Torresdale Hospital • Thomas Jefferson University Hospital • Jefferson Hospital for Neuroscience • Jefferson Methodist Hospital • Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania • Pennsylvania Hospital • Penn Presbyterian Medical Center TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ........................................2 Philadelphia County, PA ..................................127 1. Center City .........................................................128 Partners ....................................................13 2. Far North Philadelphia ......................................130 1. Introduction .......................................................13 3. Far Northeast Philadelphia ...............................134 2. Participating Hospitals and Health Systems ....14 4. Lower Northeast Philadelphia ...........................138 a. Hospital Profiles 5. North Philadelphia – East .................................142 i. Overview of Hospital 6. North Philadelphia – West ................................146 ii. Past CHNA and Community 7. Northwest -

Philadelphia Housing Authority

THE PHILLY PRIMER: Housing Resources for People with Disabilities WINTER 2009 THE PHILLY PRIMER: Housing Resources for People with Disabilities Fourth Printing — December 2009 A Publication of the Technical Assistance Program (TAP) Written by: Maggie B. McCullough, MBMconsulting Revised by: Diana T. Myers and Associates, Inc. Edited by: Diana Myers, Diana T. Myers and Associates, Inc. Diana T. Myers and Associates, Inc. 6 South Easton Road, Glenside, PA 19038 This publication was funded by the City of Philadelphia’s Office of Housing and Community Development, and is available online at the TAP website: www.newsontap.org/primer.html. Acknowledgements Information included in this Guide was obtained from a number of organizations, their publications and web sites. The Office of Housing and Community Development wishes to recognize the following organi- zations and resources, in particular, for their invaluable contributions to this Guide: Philadelphia Association of Community Development Corporations (PACDC) Philadelphia Corporation on Aging (PCA) Housing Resources for the Elderly in Philadelphia Philadelphia Housing Authority (PHA) Pennsylvania Housing Finance Agency (PHFA) Pennsylvania Department of Public Welfare, Office of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services Compendium of Housing Programs in Pennsylvania Self-Determination Housing Project of Pennsylvania My Own Keys CHOICES: A Housing Resource Guide Homeownership Training Program for People with Disabilities TAIG Development Services Corporation and Liberty Resources, Inc. The Philadelphia Homeownership Demonstration Project for Persons with Disabilities U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Diana T. Myers and Associates would also like to thank the people who reviewed draft versions of this guide to ensure that all of the information provided here is up-to-date. -

Philadelphia

A report from March 2016 Katye Martens/The Pew Charitable Trusts Philadelphia: The State of the City A 2016 Update Overview Philadelphia in 2016 is a growing city undergoing a sweeping transformation, most evident in the age and diversity of those who live here. The city’s population has risen for nine consecutive years, up another 5,880 in the most recent count. The increase since 2006 stands at 78,732, a stark reversal after a decrease of nearly 600,000 over the previous five decades. More compelling, though, are some of the factors that underlie the city’s growth. One is age. As the United States has gotten older, Philadelphia has become younger—largely because of the growth of the city’s young adult population, the much-discussed millennials. A decade ago, Philadelphia had a median age of 35.3, only a year below the nation’s 36.4. In the most recent census, the city’s age was down to 33.8, while the national figure had risen to 37.7—a difference of nearly four years. Remarkably, this happened over a time in which the number of children in the city was declining. Philadelphia is again a city of immigrants, as it had been for most of its history—but not for much of the 20th century. As recently as 1990, Philadelphia had barely more than 100,000 foreign-born residents. Today, it has in excess of 200,000, mostly from Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean, with no single nationality accounting for more than 13 percent of the whole. -

State Transportation Commission 2015 Twelve Year Program Development Regional Results of the Survey and Public Feedback From

State Transportation Commission 2015 Twelve Year Program Development Regional results of the survey and public feedback from August thru November 2013 Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission (DVRPC) Version 01-2014 Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission MPO Total Visitors 730 Mobility Concerns Traffic congestion is growing and resources are limited to build additional capacity. As a result, transportation agencies are exploring ways to manage demand, operate efficiently, and improve capacity. Using a scale of 1-5, for each mobility concern, please rank how important each mobility concern is to you, with one being ‘Not Important’ and 5 being ‘Very Important’. Passenger Ridership on the Keystone Corridor has doubled since 2000 making it !mtrak’s fourth-busiest route in the Rail nation. Rail infrastructure improvements are critical to timely service. Responded With an Average Rank of 4.35 Congestion Relieve traffic congestion by addressing bottlenecks and other traffic relief measures. Responded With an Average Rank of 4.26 Transit Implementing new technologies improves service. Responded With an Average Rank of 4.15 Signals Modernization of traffic signals streamlines traffic flow and reduces fuel costs for motorists. Responded With an Average Rank of 4.07 Incident This legislation would allow for the safe, quick clearance of traffic incidents from the roadway. Responded With an Average Rank of 3.59 Freight Rail $500 billion in goods and services travel through PA each year. That investment would grow with upgrades to accommodate intermodal changes such as emerging needs from the natural gas industry and double- stack train access to our ports. Responded With an Average Rank of 3.53 Real T ime This involves the use of dynamic message signs, PennDOT’s 511P!.com system and social media. -

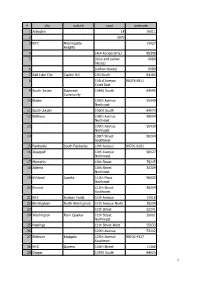

SQL Abfragenergebnis

# city suburb road postcode 1 Arlington 14 76011 2 2870 3 NYC Morningside 10027 Heights 4 (4x4 Access Only) 85396 5 (lbue and yellow 6089 blazes) 6 (yellow blazes) 6089 7 Salt Lake City Capitol Hill 100 South 84180 8 103rd Avenue 98375-9511 Court East 9 South Jordan Daybreak 10460 South 84095 Community 10 Blaine 105th Avenue 55449 Northeast 11 South Jordan 10600 South 84070 12 Bellevue 106th Avenue 98004 Northeast 13 109th Avenue 55434 Northeast 14 109th Street 98204 Southwest 15 Fairbanks South Fairbanks 10th Avenue 99701-6161 16 Issaquah 10th Avenue 98027 Northwest 17 Memphis 10th Street 79245 18 Atlanta 10th Street 30309 Northeast 19 Kirkland Juanita 110th Place 98033 Northeast 20 Everett 112th Street 98204 Southwest 21 NYC Hudson Yards 11th Avenue 10018 22 Birmingham North Birmingham 11th Avenue North 35234 23 11th Street 52241 24 Washington Penn Quarter 11th Street 20001 Northwest 25 Hastings 11th Street West 55033 26 120th Avenue 53142 27 Bellevue Eastgate 125th Avenue 98005-4317 Southeast 28 NYC Queens 126th Street 11368 29 Draper 12970 South 84020 1 # city suburb road postcode 30 NYC Chelsea 12th Avenue 10001 31 Nashville-Davidson East Nashville 12th Avenue South 37203 32 12th Street 54904 33 Marina Marina 13th Street 93933 34 Atlanta Rockdale 13th Street 30309 Northeast 35 NYC Queens 144th Street 11435 36 Cincinnati Over-The-Rhine 14th St 45202 37 Miami Beach 14th Street 33139 38 Washington Columbia Heights 14th Street 20011 Northwest 39 150th Avenue 56073 40 151st Street 60452 41 152nd Street 60445 42 153rd Street East 98360 -

Philadelphia 2021: the State of the City April 2021 About This Report

Philadelphia The the State 2021: of City Report April 2021 April 2021 Philadelphia 2021 The State of the City About this report The annual “State of the City” report is part of The Pew Charitable Trusts’ ongoing work in Philadelphia. Staff members Katie Martin, Jason Hachadorian, and Donna Leong gathered the data and assembled the report. Larry Eichel, senior adviser for Pew’s Philadelphia research and policy initiative, helped write and edit the publication, along with Elizabeth Lowe and Erika Compart. Ned Drummond and Cara Bahniuk created the graphics and designed the report. Contact: Elizabeth Lowe, communications officer Email: [email protected] Phone: 215-575-4812 Project website: pewtrusts.org/philaresearch The Pew Charitable Trusts is driven by the power of knowledge to solve today’s most challenging problems. Pew applies a rigorous, analytical approach to improve public policy, inform the public, and invigorate civic life. Contents 1 A Troubling Year 15 Demographics 27 Education 35 Government 43 Health 57 Housing 69 Jobs and the Economy 81 Public Safety 91 Transportation, Infrastructure, and the Environment 98 Photo Captions A Troubling Year In so many ways, 2020 was a troubling year for Philadelphia, one that raised profound questions about its future. The numbers tell the story of a city facing tremendous challenges, not just from the pandemic and its economic impact but from rising drug overdose deaths and gun violence as well. Philadelphia recorded more than 96,000 COVID-19 cases and 2,500 deaths from the virus in 2020, with the death toll surpassing 3,000 by mid-February 2021. -

NGT Priority Acquisition Plan

NEIGHBORHOOD GARDENS TRUST Priority Acquisition Plan Prepared by Reinvestment Fund’s Policy Solutions Group and LRSLAstudio, Inc. March 2016 ` ` THANK YOU This project was financed in part by a grant from the Community Conservation Partnerships Program, Keystone Recreation, Park and Conservation Fund, under the administration of the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Bureau of Recreation and Conservation. Additionally, this study would not have been possible without the support of: Pennsylvania Horticultural Society Public Interest Law Center of Philadelphia, Garden Justice Legal Initiative African American Collaborative Obesity Research Network, ESHE Community Pilot Neighborhood Gardens Trust Board of Trustees Amy Laura Cahn, Public Interest Law Center of Philadelphia* Phoebe Coles, Community Marketing Solutions J.J. Cutler, Futurestep Korn Ferry Joanne Dahme, Philadelphia Water Department* Gregory Duffy, Duane Morris, LLP* Alison Hastings, Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission Bob Jobin, Bouvier Community Garden Suku John, East Park Revitalization Alliance Margaret McCarvill, NGT Board President, MMM Consulting* Deborah McColloch, Philadelphia Office of Housing and Community Development Julianne Schrader Ortega, Pennsylvania Horticultural Society* Carla Puppin, Bel Arbor Community Garden Joe Revlock, Summer-Winter Community Garden Viery Ricketts-Thomas, Glenwood Green Acres Judith Smeltzer Janice Trapp, Aspen Farms Peter Williamson, NGT Board Vice President/Treasurer, Natural Lands Trust* NGT Staff -

Brought to You by the Philadelphia Eviction Prevention Project

BROUGHT TO YOU BY THE PHILADELPHIA EVICTION PREVENTION PROJECT 0 Brought to you by the Philadelphia Eviction Prevention Project Clarifi Community Legal Services Legal Clinic for the Disabled SeniorLAW Center Tenant Union Representative Network Philadelphia VIP All of the information provided in this guidebook, as well as additional resources and sample letters, is available at www.phillytenant.org. Call 267-443-2500 to reach the Tenant Aid Referral Line. Printing supported by the Office of Community Empowerment & Opportunity (CEO). CEO is Philadelphia's Community Action Agency, funded in part by the PA Department of Community and Economic Development. Updated 10/2019 1 PHILLY TENANT RESOURCE GUIDE HOUSING EVICTION Page 3 Page 11 UTILITIES FOOD Page 15 Page 18 HEALTH WORK Page 19 Page 22 EXTRA HELP Veterans Page 23 Immigrants Page 23 Disabilities Page 24 Seniors Page 24 LGBTQ Page 25 Domestic Violence Page 25 2 HOUSING WHERE CAN I GO FOR EMERGENCY SHELTER? All Days and Times: Men and Women Aged 21 and Younger Covenant House 31 E. Armat Street 215-951-5411 Monday-Friday, 7am-3pm After 3pm and Weekends Single Women & Families For Families Apple Tree Family Center The Red Shield 1430 Cherry St (near Cherry and 15th) 715 N Broad St (near Broad & Fairmount) 215-686-7150, 7151, 7152, or 7153 215-787-2887 Single Men For Single Women Roosevelt Darby Center House of Passage Kirkbride Center 802 N Broad St (near Broad & Fairmount) 111 N 48th St (near 48th & Haverford) 215-685-3700 215-471-2017 or 267-713-7778 For Single Men Station House 2601 N Broad St (near Broad & Lehigh) 215-225-9230 Homeless Outreach Hotline at 215-232-1984 Philadelphia Domestic Violence Hotline at 866-723-3014 3 HOUSING WHERE CAN I GO FOR RENT OR SECURITY DEPOSIT ASSISTANCE? Office of Homeless Services (OHS) 1430 Cherry Street (Center City) Monday-Friday, 9am-4pm Low-income tenants only. -

Community Health Needs Assessment Implementation Plan

Table of Contents Overview of Jefferson Health....................................................................................................2 Overview of the Community Health Needs Assessment and Prioritization Process……………. 4 Overview of the Implementation Plan………………………………………………………………………………….5 Domain: Substance Use and Abuse ……………………………………………………………………………………10 Domain: Behavioral Health…………………………………………………………………………………………………14 Domain: Access to Affordable, Culturally Appropriate Primary and Specialty Care…………..17 Domain: Chronic Disease Prevention and Management…………………………………………………….25 Domain: Social Determinants of Health ………………………………….............................................39 Access to affordable, culturally appropriate primary and specialty care Jefferson Health Community Health Implementation Plan Overview of Jefferson Health Overview of “Jefferson Health” Jefferson Health Hospitals and Thomas Jefferson University are partners in providing excellent clinical and compassionate care for our patients in the Philadelphia region, educating the health professionals of tomorrow in a variety of disciplines and discovering new knowledge that will define the future of clinical care. Jefferson Health (JH), the clinical arm of Thomas Jefferson University, has grown from a three‐ hospital academic health center in 2015 to a 14‐hospital health system through mergers and combinations that include former hospitals at Abington Health, Aria Health, Kennedy Health and Magee Rehabilitation. Jefferson Health has seven Magnet®‐designated hospitals (recognized by the ANCC for nursing excellence); one of the largest faculty‐based telehealth networks in the country; the NCI‐designated Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center (one of only 70 in the country); and more than 40 outpatient and urgent care locations. Thomas Jefferson University Hospital (TJUH), is one of only 14 hospitals in the country that is a Level 1 Trauma Center and a federally designated Regional Spinal Cord Injury Center. It also continues its national record of excellence with recognition from U.S. -

2019 Conference

2019 CONFERENCE TWEET @PHILLYCDCS #EQUITABLEPHILLY WEDNESDAY, JUNE 26TH | 8:00AM to 5:00PM THURSDAY, JUNE 27TH | 8:00AM to 2:00PM WWW.PACDC.ORG A FOREWORD ON EQUITABLE DEVELOPMENT FROM PACDC Special Thanks to Our Four years ago, PACDC members worked Conference Planning Committee together to craft Beyond Gentrification, • Fred Bañuelos, Federal Home Loan Bank of Pittsburgh Toward Equitable Neighborhoods: An Equitable • Jeffrey Barg, Pennsylvania Horticultural Development Policy Platform for Philadelphia. Society • Rickie Brawer, Thomas Jefferson This was our agenda for the next City Council University Hospitals session and Mayoral Administration to • Carolyn Brown, Office of Community Empowerment and Opportunity ensure that long-term residents and small • David Buches, Federal Home Loan Bank businesses benefitted from Philadelphia’s new of Pittsburgh • Abby Cabrera, Thomas Jefferson development, investment, and growth. University Hospitals • Rhonda Coleman, Public Health At the time, federal funding for community development Management Corporation in Philadelphia had been in decline, and local funding had • Sydney Diavua, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia been stagnant. But because we worked together, and • Bryan Fenstermaker, Passyunk Avenue with allies, to advance our Equitable Development Policy Revitalization Corporation Platform and partnered with strong champions in City • Rose Gray, Asociación Puertorriqueños Council and the Mayor’s Administration, things sure en Marcha • Susan Jouard, NeighborWorks America have changed! • Melissa Kim, LISC Philadelphia We’ve won more than $353 million in added local funding • Melissa Long, City of Philadelphia over FY16 – FY23 for affordable housing and community Division of Housing and Community Development economic development, from boosting the Philadelphia • Lynn Mandarano, Temple University Tyler Housing Trust Fund to expanding the CDC Tax Credit School of Art program, increasing funds for commercial corridor • Stephanie Michel, North 5th Street Revitalization Project programs, and more.