Representations Involving Fiduciary Entities: Who Is the Client?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fiduciary Roles in Your Estate Plan in Illinois WHAT IS a FIDUCIARY ROLE?

FIDUCIARY ROLES IN YOUR ESTATE IN ILLINOIS PLAN “A “fiduciary” role refers to a position of trust, often involving money or property that has been entrusted to the individual in the fiduciary role.” CURTIS J. FORD ILLINOIS ATTORNEY A number of important decisions must be made when you create your estate plan. While many of these decisions relate to the disposition of estate assets should you become incapacitated or die, some of the most important decisions you will need to make have nothing to do with assets. Instead, those decisions involve fulfilling fiduciary roles in your estate plan. All too often individuals are chosen to fill fiduciary roles within an estate plan without giving adequate thought to the choices. A better understanding of the various fiduciary roles within your estate plan and the importance of choosing the right person for the job may prevent you from making this mistake. 2 Fiduciary Roles in Your Estate Plan in Illinois www.nashbeanford.com WHAT IS A FIDUCIARY ROLE? A “fiduciary” role refers to a position of trust, often involving money or property that has been entrusted to the individual in the fiduciary role. A fiduciary must use the utmost care when handling money or assets entrusted to him or her because those assets are intended to be used for the benefit of a third party beneficiary. Furthermore, a fiduciary is expected to make prudent investment decisions and not take risks with assets unless specifically directed to do so by the person who appointed the fiduciary. In short, a fiduciary should be more careful with assets entrusted to his or her care than the fiduciary would be with his or her own assets. -

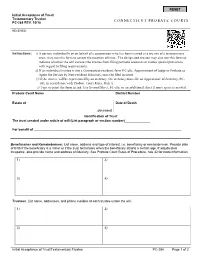

Initial Acceptance of Trust/ Testamentary Trustee PC-284 REV. 10/18

Initial Acceptance of Trust/ Testamentary Trustee CONNECTICUT PROBATE COURTS PC-284 REV. 10/18 RECEIVED: Instructions: 1) A person, individually or on behalf of a corporation who has been named as a trustee of a testamentary trust, may use this form to accept the position of trust. The designated trustee may also use this form to indicate whether the will excuses the trustee from filing periodic accounts or makes special provisions with regard to filing requirements. 2) If an individual trustee is not a Connecticut resident, form PC-482, Appointment of Judge or Probate as Agent for Service by Non-resident Fiduciary, must be filed in court. 3) If the trustee will be represented by an attorney, the attorney must file an Appearance of Attorney, PC- 183, in accordance with Probate Court Rules, Rule 5. 4) Type or print the form in ink. Use Second Sheet, PC-180, or an additional sheet if more space is needed. Probate Court Name District Number Estate of Date of Death ,deceased Identification of Trust The trust created under article of will (List paragraph or section number)______________ For benefit of _________________________________________________________________________________ Beneficiaries and Remaindermen: List name, address and type of interest, i.e, beneficiary or remainderman. Provide date of birth if the beneficiary is a minor or if the trust terminates when the beneficiary attains a certain age. If adjudicated incapable, also provide name and address of fiduciary. See Probate Court Rules of Procedure, rule 32 for more information. 1) 2) 3) 4) Trustees: List name, addresses, and phone number of each trustee under the will. -

Trust Administration Guidelines for Trustees

LAW OFFICES OF MICHAEL E. GRAHAM 10343 HIGH STREET, SUITE ONE TRUCKEE, CALIFORNIA 96161-0116 TELEPHONE 530.587.1177 P FACSIMILE 530.587.0707 MICHAEL E. GRAHAM † [email protected] TRUST ADMINISTRATION GUIDELINES FOR TRUSTEES I. INTRODUCTION The average person has had little experience dealing with trusts and often has many questions upon becoming a Trustee for the first time. Since you will be the Trustee of a Trust, the purpose of this memo is to try to anticipate your questions by providing a general overview of how Trusts work and your duties and responsibilities as Trustee. Through our experience in helping people administer trusts, we have found that many individuals have unrealistic expectations concerning the way living trusts operate following a death. It is true that a living trust in many cases drastically reduces the costs and delays involved in passing on assets at death. A living trust accomplishes this feat by avoiding probate. However, even without a probate, many administrative chores have to be completed, legal documents prepared, taxes returns filed, and other matters that take time and cost money. II. TRUSTS IN GENERAL A. What is a Trust? A trust is a legal relationship, usually evidenced by a written document called a "Declaration of Trust" or "Trust Agreement," whereby one person, called the "Trustor," transfers property to another person, called the "Trustee," who holds the property for the benefit of another person, called the "Beneficiary." The same person may occupy more than one position at a time. For example, in the typical living trust, as long as the Trustor is alive, the Trustor is also the Trustee and Beneficiary. -

Probate: Connecticut

Resource ID: w-009-4550 Probate: Connecticut JESSIE A. GILBERT, SUSAN HUFFARD, AND KATHERINE A. MCALLISTER, CUMMINGS & LOCKWOOD LLC WITH PRACTICAL LAW TRUSTS & ESTATES Search the Resource ID numbers in blue on Westlaw for more. A Q&A guide to the laws of probate in Courts have jurisdiction over the estates of decedents domiciled in Connecticut and the estates of non-domiciliaries if: Connecticut. This Q&A addresses state laws and The decedent last resided in Connecticut. customs that impact the process of an estate The decedent left real or tangible personal property located in proceeding, including the key statutes and rules Connecticut. related to estate proceedings, the different types The decedent maintained a bank account in Connecticut or any bank account of the decedent is located in Connecticut. of estate proceedings available in Connecticut, The decedent left evidence of other intangible personal property in and the processes for opening an estate, Connecticut (for example, stock certificates or bonds). appointing an estate fiduciary, administering Any executor or trustee named in the will resides in Connecticut or, in the case of a bank or trust company, has an office in the estate, handling creditor claims, and closing Connecticut. the estate. Any cause of action in favor of the decedent arose in Connecticut or any debtor of the decedent resides in Connecticut. (Conn. Gen. Stat. Ann. § 45a-287.) KEY STATUTES AND RULES A determination of domicile at the time of death of any deceased person is made by the Probate Court, but any finding of domicile 1. What are the state laws and rules that govern estate by the Probate Court is subject to a later determination of domicile proceedings? in connection with the Connecticut estate tax (Conn. -

Estate Planning Newsletter

estate planning newsletter spring 2012 hogefenton.com Our 2012 newsletter focuses on practical issues you or loved ones may face and (for once) includes no long article about taxes. Your preferences concerning end of life care are the most personal part of your planning, so we’ve included an article about some planning tools you may consider. Individuals considering serving as trustees or wrestling with choosing trustees should enjoy the article written from the first person perspective of a novice trustee. Our work with our firm’s robust family law practice led to a useful article on estate planning and divorce. Our discussion of taxes is brief, but important: 2012 is the final year for the high $5M lifetime estate, gift and generation-skipping tax exclusions. This is a “one-time offer” from Uncle Sam: the tax exemptions drop to $1M in 2013 under the current law, unless Congress changes the law again. The high exemptions and the expectation that asset values will increase present a unique opportunity for clients to make large wealth transfers to their families and reduce their future taxable estates. If you are considering significant wealth transfers, please talk to us soon. We expect the end of 2013 will be very busy for our team. © J.B. Handelsman/The New Yorker Collection/www.cartoonbank.com AHCDs, DNR Orders, Living Wills, POLSTs, …… We routinely recommend that each estate planning client complete an Advance Health What does it all mean? Care Directive (AHCD), appointing an agent to make health care decisions for the client if he is unable to make those decisions himself. -

Trust Law Implications of Proposed Regulatory Reform of Mutual Fund Governance Structures

Trust Law Implications of Proposed Regulatory Reform of Mutual Fund Governance Structures A Background Research Report to Concept Proposal 81-402 of the Canadian Securities Administrators Prepared by David P. Stevens Goodman and Carr LLP 200 King Street West, Suite 2300 Toronto, ON M5H 3W5 March 1, 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND ................................................................................1 1. INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................1 2. BACKGROUND .....................................................................................................4 II. THE MUTUAL FUND INDUSTRY ......................................................................................12 3. CURRENT STRUCTURES AND PRACTICES ..................................................12 Common Mutual Fund Structures .........................................................................12 The Importance of the Investor/Manager Relationship..........................................15 The Fiduciary Conflicts of the Manager ................................................................18 Classifications of Mutual Funds - The Legal Constitution ...................................21 4. REASONS FOR COMMON STRUCTURES ......................................................24 Taxation Reasons...................................................................................................25 Governance Reasons..............................................................................................29 -

Breach of Fiduciary Duty Claims

CLAIMS ARISING FROM A BREACH OF A FIDUCIARY DUTY This manuscript is intended to serve as a reference for judges who are handling civil cases involving legal claims arising from fiduciary or confidential relationships between the litigants. In many instances, these claims are labeled as constructive fraud claims. In the first section of this paper, the essential elements of these claims are discussed. The second section of this paper addresses particular relationships which may or may not constitute a fiduciary or confidential relationship. WHAT POLICIES ARE ADVANCED BY THIS BODY OF LAW Essentially, the law in this area seeks to prevent fraud and to protect individuals who are in a relatively vulnerable position. These policies are reflected in the following statements from North Carolina appellate courts: “Fraud, actual and constructive, is so varied in form many courts have refused to precisely define it, lest the definition itself be turned into an avenue of escape by the crafty and unscrupulous. Nevertheless, the legal principles that govern constructive fraud claims are well established. One is that a case of constructive fraud is established when proof is presented that a position of trust and confidence was taken advantage of to the hurt of the other.” Terry v. Terry, 302 N.C. 77, 273 S.E. 2d 674 (1981); Link v. Link, 278 N.C. 181, 179 S.E. 2d 697 (1971). “Any transaction between persons so situated is 'watched with extreme jealousy and solicitude; and if there is found the slightest trace of undue influence or unfair advantage, redress will be given to the injured party.'" See Eubanks v. -

Downloads/Response to Ministry of A.G..Doc> (Posted March 2004) (Last Accessed November 27, 2005)

STILLBORN AUTONOMY: WHY THE REPRESENTATION AGREEMENT ACT 0¥ BRITISH COLUMBIA FAILS AS ADVANCE DIRECTIVE LEGISLATION by JOAN L. RUSH Barrister and Solicitor B.COMM., University of British Columbia, 1981 LL.B., University of British Columbia, 1982 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIRMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF LAWS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (LAW) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA December 2005 © Joan Linda Rush, 2005 ABSTRACT An advance directive is an instruction made by a competent person about his or her preferred health care choices, should the person become incapable to make treatment decisions. Legal recognition of advance directives has developed over the last half century in response to medical advances that can prolong the life of a patient who is no longer sentient, and who has decided to forego some or all treatment under such circumstances. Two types of directive have emerged in the law: an instructional directive, in which a person sets out treatment choices, and a proxy directive, which enables the person to appoint a proxy to make treatment decisions. Development of the law has been impeded by fear that advance directives diminish regard for the sanctity of life and potentially authorize euthanasia or assisted suicide. In Canada, this fear explains the continued existence of outdated criminal law prohibitions and contributes to provincial advance directive legislation that is disharmonized and restrictive, in some provinces limiting personal choice about the type of advance directive that can be made. The British Columbia Representation Agreement Act (RAA)1 is an example of such restrictive legislation. -

Trust Privacy Frances H

Cornell Law Review Volume 93 Article 14 Issue 3 March 2008 Trust Privacy Frances H. Foster Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Frances H. Foster, Trust Privacy, 93 Cornell L. Rev. 555 (2008) Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr/vol93/iss3/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TRUST PRIVACY Frances H. Fostert INTRODUCTION ................................................. 555 I. THE PUBLIC/PRIVATE DISTINCTION BETWEEN WILLS AND WILL-LIKE TRUSTS .......................................... 559 II. THE HUMAN BENEFITS OF TRUST PRIVACY ................. 567 A . Settlors ............................................. 567 1. Control over Identity and Reputation ............... 567 2. Control over Property.............................. 570 B . T rustees ............................................ 573 C. Beneficiaries ........................................ 575 1. Protectionfrom the Outside World .................. 575 2. Protectionfrom Each Other ........................ 576 3. Protectionfrom Themselves ........................ 581 D . Third Parties ....................................... 582 III. THE HUMAN COSTS OF TRUST PRIVACY .................... 584 A . Settlors ............................................ -

Glossary of Legal Terms

ILM Factsheet Glossary of legal terms Prepared for ILM by Wilsons A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | L | M | N | O | P | R | S | T | U | V | W A Abatement Reduction of a gift in a Will where there are insufficient assets to pay it in full. Limited grant of probate (interim grant). Allows the Ad colligenda bona, grant administrator to collect in and preserve estate assets, but not to distribute them. Ademption Failure of a gift in a Will. High Court action under Part 64 Civil Procedure Rules 1998. Administration Action Used to secure proper administration of the estate. Person responsible for winding up an estate where the Administrator deceased did not leave a Will. Advancement/Appointment, Authorises trustees to pay capital out of a trust fund for power of beneficiaries of that trust. Affidavit Sworn statement. Alternative dispute resolution. Methods used to resolve ADR disputes without litigation. Reply made by a caveator where a warning has been issued Appearance to warning in respect of their caveat. Once entered, a grant will not be issued other than by court order. Giving the deceased’s property to a beneficiary in its Appropriation present form, in satisfaction of a gift in a Will. Statement in a Will recording the manner in which it was Attestation clause executed. Attorney Person authorised to act in another’s place. B Person entitled to the benefit of property held on trust; Beneficiary person receiving a gift in a Will. Bequest Gift in a Will. C ILM Factsheet Glossary of legal terms Without prejudice offer to settle a claim. -

ACTEC 2014 Fall Meeting Musings November 2014

ACTEC 2014 Fall Meeting Musings November 2014 The American College of Trust and Estate Counsel is a national organization of approximately 2,600 lawyers elected to membership. One of its central purposes is to study and improve trust, estate and tax laws, procedures and professional responsibility. Learn more about ACTEC and access the roster of ACTEC Fellows at www.actec.org. This summary reflects the individual observations of Steve Akers from the seminars at the 2014 Fall Meeting and does not purport to represent the views of ACTEC as to any particular issues. Steve R. Akers Senior Fiduciary Counsel — Southwest Region, Bessemer Trust 300 Crescent Court, Suite 800 Dallas, TX 75201 214-981-9407 [email protected] www.bessemer.com TABLE OF CONTENTS Items 1-10 are observations from a panel by Henry Christensen III and Miriam W. Henry—To Trust or Not to Trust: That is the Question—Working with Foreign Trusts and Louisiana Trusts ... 1 1. History of Trusts in Louisiana ........................................................................................ 1 2. Unique Characteristics of Louisiana Trusts ..................................................................... 1 3. Usufructs in Louisiana ................................................................................................. 3 4. Other Trust Substitutes in Louisiana .............................................................................. 3 5. Practical Considerations for Non-Louisiana Residents ...................................................... 3 6. Civil Law -

Probate Glossary

PROBATE GLOSSARY A ACCOUNTING An act or system of making up or settling accounts; a statement of account, or a debit and credit in financial transactions. PROBATE: Final Accounting Report and Distribution. ADEMPTION The failure of a specific bequest of property because the property is no longer owned by the testator at the time of his death. AD LITEM For the suit; for purposes of the suit; pending the suit. (See guardian ad litem.) ADMINISTRATOR A person (sometimes a family member) appointed by the court to administer the estate of a person who died without a will (i.e., a Personal Representative). (See also, general administrator, public administrator, and special administrator.) ADMINISTRATOR WITH WILL ANNEXED A person appointed by the court to administer the estate of a person who died with a will, but the will either fails to nominate an executor or the named executor is unable to serve. ADOPTION The judicial act creating the legal parental relationship with no genetic linkage exists. ATTESTATION The act of witnessing the signing of a document by another, and the signing of the document as a witness. Thus, a will requires both the signature by the person making the will and attestation by at least two witnesses. ATTESTATION CLAUSE The clause generally at the end of an instrument wherein the witnesses certify that the instrument has been executed before them, and the manner of the execution of same. A certificate certifying as to the facts and circumstances attending execution of a will. ATTORNEY-IN-FACT The individual who is designated in the power of attorney document to act on behalf of another.