Au Revoir, Will Contests: Comparative Lessons for Preventing Will Contests

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Limits of Punishment Transitional Justice and Violent Extremism

i n s t i t u t e f o r i n t e g r at e d t r a n s i t i o n s The Limits of Punishment Transitional Justice and Violent Extremism May, 2018 United Nations University – Centre for Policy Research The UNU Centre for Policy Research (UNU-CPR) is a UN-focused think tank based at UNU Centre in Tokyo. UNU-CPR’s mission is to generate policy research that informs major UN policy processes in the fields of peace and security, humanitarian affairs, and global development. i n s t i t u t e f o r i n t e g r at e d t r a n s i t i o n s Institute for Integrated Transitions IFIT’s aim is to help fragile and conflict-affected states achieve more sustainable transitions out of war or authoritarianism by serving as an independent expert resource for locally-led efforts to improve political, economic, social and security conditions. IFIT seeks to transform current practice away from fragmented interventions and toward more integrated solutions that strengthen peace, democracy and human rights in countries attempting to break cycles of conflict or repression. Cover image nigeria. 2017. Maiduguri. After being screened for association with Boko Haram and held in military custody, this child was released into a transit center and the care of the government and Unicef. © Paolo Pellegrin/Magnum Photos. This material has been supported by UK aid from the UK government; the views expressed are those of the authors. -

Tol, Xeer, and Somalinimo: Recognizing Somali And

Tol , Xeer , and Somalinimo : Recognizing Somali and Mushunguli Refugees as Agents in the Integration Process A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Vinodh Kutty IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY David M. Lipset July 2010 © Vinodh Kutty 2010 Acknowledgements A doctoral dissertation is never completed without the help of many individuals. And to all of them, I owe a deep debt of gratitude. Funding for this project was provided by two block grants from the Department of Anthropology at the University of Minnesota and by two Children and Families Fellowship grants from the Annie E. Casey Foundation. These grants allowed me to travel to the United Kingdom and Kenya to conduct research and observe the trajectory of the refugee resettlement process from refugee camp to processing for immigration and then to resettlement to host country. The members of my dissertation committee, David Lipset, my advisor, Timothy Dunnigan, Frank Miller, and Bruce Downing all provided invaluable support and assistance. Indeed, I sometimes felt that my advisor, David Lipset, would not have been able to write this dissertation without my assistance! Timothy Dunnigan challenged me to honor the Somali community I worked with and for that I am grateful because that made the dissertation so much better. Frank Miller asked very thoughtful questions and always encouraged me and Bruce Downing provided me with detailed feedback to ensure that my writing was clear, succinct and organized. I also have others to thank. To my colleagues at the Office of Multicultural Services at Hennepin County, I want to say “Thank You Very Much!” They all provided me with the inspiration to look at the refugee resettlement process more critically and dared me to suggest ways to improve it. -

Introduction to Law and Legal Reasoning Law Is

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION TO LAW AND LEGAL REASONING LAW IS "MAN MADE" IT CHANGES OVER TIME TO ACCOMMODATE SOCIETY'S NEEDS LAW IS MADE BY LEGISLATURE LAW IS INTERPRETED BY COURTS TO DETERMINE 1)WHETHER IT IS "CONSTITUTIONAL" 2)WHO IS RIGHT OR WRONG THERE IS A PROCESS WHICH MUST BE FOLLOWED (CALLED "PROCEDURAL LAW") I. Thomas Jefferson: "The study of the law qualifies a man to be useful to himself, to his neighbors, and to the public." II. Ask Several Students to give their definition of "Law." A. Even after years and thousands of dollars, "LAW" still is not easy to define B. What does law Consist of ? Law consists of enforceable rule governing relationships among individuals and between individuals and their society. 1. Students Need to Understand. a. The law is a set of general ideas b. When these general ideas are applied, a judge cannot fit a case to suit a rule; he must fit (or find) a rule to suit the unique case at hand. c. The judge must also supply legitimate reasons for his decisions. C. So, How was the Law Created. The law considered in this text are "man made" law. This law can (and will) change over time in response to the changes and needs of society. D. Example. Grandma, who is 87 years old, walks into a pawn shop. She wants to sell her ring that has been in the family for 200 years. Grandma asks the dealer, "how much will you give me for this ring." The dealer, in good faith, tells Grandma he doesn't know what kind of metal is in the ring, but he will give her $150. -

How Informal Justice Systems Can Contribute

United Nations Development Programme Oslo Governance Centre The Democratic Governance Fellowship Programme Doing Justice: How informal justice systems can contribute Ewa Wojkowska, December 2006 United Nations Development Programme – Oslo Governance Centre Contents Contents Contents page 2 Acknowledgements page 3 List of Acronyms and Abbreviations page 4 Research Methods page 4 Executive Summary page 5 Chapter 1: Introduction page 7 Key Definitions: page 9 Chapter 2: Why are informal justice systems important? page 11 UNDP’s Support to the Justice Sector 2000-2005 page 11 Chapter 3: Characteristics of Informal Justice Systems page 16 Strengths page 16 Weaknesses page 20 Chapter 4: Linkages between informal and formal justice systems page 25 Chapter 5: Recommendations for how to engage with informal justice systems page 30 Examples of Indicators page 45 Key features of selected informal justice systems page 47 United Nations Development Programme – Oslo Governance Centre Acknowledgements Acknowledgements I am grateful for the opportunity provided by UNDP and the Oslo Governance Centre (OGC) to undertake this fellowship and thank all OGC colleagues for their kindness and support throughout my stay in Oslo. I would especially like to thank the following individuals for their contributions and support throughout the fellowship period: Toshihiro Nakamura, Nina Berg, Siphosami Malunga, Noha El-Mikawy, Noelle Rancourt, Noel Matthews from UNDP, and Christian Ranheim from the Norwegian Centre for Human Rights. Special thanks also go to all the individuals who took their time to provide information on their experiences of working with informal justice systems and UNDP Indonesia for releasing me for the fellowship period. Any errors or omissions that remain are my responsibility alone. -

Fiduciary Roles in Your Estate Plan in Illinois WHAT IS a FIDUCIARY ROLE?

FIDUCIARY ROLES IN YOUR ESTATE IN ILLINOIS PLAN “A “fiduciary” role refers to a position of trust, often involving money or property that has been entrusted to the individual in the fiduciary role.” CURTIS J. FORD ILLINOIS ATTORNEY A number of important decisions must be made when you create your estate plan. While many of these decisions relate to the disposition of estate assets should you become incapacitated or die, some of the most important decisions you will need to make have nothing to do with assets. Instead, those decisions involve fulfilling fiduciary roles in your estate plan. All too often individuals are chosen to fill fiduciary roles within an estate plan without giving adequate thought to the choices. A better understanding of the various fiduciary roles within your estate plan and the importance of choosing the right person for the job may prevent you from making this mistake. 2 Fiduciary Roles in Your Estate Plan in Illinois www.nashbeanford.com WHAT IS A FIDUCIARY ROLE? A “fiduciary” role refers to a position of trust, often involving money or property that has been entrusted to the individual in the fiduciary role. A fiduciary must use the utmost care when handling money or assets entrusted to him or her because those assets are intended to be used for the benefit of a third party beneficiary. Furthermore, a fiduciary is expected to make prudent investment decisions and not take risks with assets unless specifically directed to do so by the person who appointed the fiduciary. In short, a fiduciary should be more careful with assets entrusted to his or her care than the fiduciary would be with his or her own assets. -

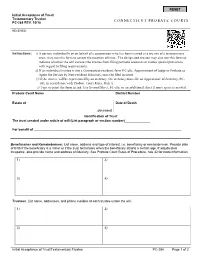

Initial Acceptance of Trust/ Testamentary Trustee PC-284 REV. 10/18

Initial Acceptance of Trust/ Testamentary Trustee CONNECTICUT PROBATE COURTS PC-284 REV. 10/18 RECEIVED: Instructions: 1) A person, individually or on behalf of a corporation who has been named as a trustee of a testamentary trust, may use this form to accept the position of trust. The designated trustee may also use this form to indicate whether the will excuses the trustee from filing periodic accounts or makes special provisions with regard to filing requirements. 2) If an individual trustee is not a Connecticut resident, form PC-482, Appointment of Judge or Probate as Agent for Service by Non-resident Fiduciary, must be filed in court. 3) If the trustee will be represented by an attorney, the attorney must file an Appearance of Attorney, PC- 183, in accordance with Probate Court Rules, Rule 5. 4) Type or print the form in ink. Use Second Sheet, PC-180, or an additional sheet if more space is needed. Probate Court Name District Number Estate of Date of Death ,deceased Identification of Trust The trust created under article of will (List paragraph or section number)______________ For benefit of _________________________________________________________________________________ Beneficiaries and Remaindermen: List name, address and type of interest, i.e, beneficiary or remainderman. Provide date of birth if the beneficiary is a minor or if the trust terminates when the beneficiary attains a certain age. If adjudicated incapable, also provide name and address of fiduciary. See Probate Court Rules of Procedure, rule 32 for more information. 1) 2) 3) 4) Trustees: List name, addresses, and phone number of each trustee under the will. -

Trust Administration Guidelines for Trustees

LAW OFFICES OF MICHAEL E. GRAHAM 10343 HIGH STREET, SUITE ONE TRUCKEE, CALIFORNIA 96161-0116 TELEPHONE 530.587.1177 P FACSIMILE 530.587.0707 MICHAEL E. GRAHAM † [email protected] TRUST ADMINISTRATION GUIDELINES FOR TRUSTEES I. INTRODUCTION The average person has had little experience dealing with trusts and often has many questions upon becoming a Trustee for the first time. Since you will be the Trustee of a Trust, the purpose of this memo is to try to anticipate your questions by providing a general overview of how Trusts work and your duties and responsibilities as Trustee. Through our experience in helping people administer trusts, we have found that many individuals have unrealistic expectations concerning the way living trusts operate following a death. It is true that a living trust in many cases drastically reduces the costs and delays involved in passing on assets at death. A living trust accomplishes this feat by avoiding probate. However, even without a probate, many administrative chores have to be completed, legal documents prepared, taxes returns filed, and other matters that take time and cost money. II. TRUSTS IN GENERAL A. What is a Trust? A trust is a legal relationship, usually evidenced by a written document called a "Declaration of Trust" or "Trust Agreement," whereby one person, called the "Trustor," transfers property to another person, called the "Trustee," who holds the property for the benefit of another person, called the "Beneficiary." The same person may occupy more than one position at a time. For example, in the typical living trust, as long as the Trustor is alive, the Trustor is also the Trustee and Beneficiary. -

Probate: Connecticut

Resource ID: w-009-4550 Probate: Connecticut JESSIE A. GILBERT, SUSAN HUFFARD, AND KATHERINE A. MCALLISTER, CUMMINGS & LOCKWOOD LLC WITH PRACTICAL LAW TRUSTS & ESTATES Search the Resource ID numbers in blue on Westlaw for more. A Q&A guide to the laws of probate in Courts have jurisdiction over the estates of decedents domiciled in Connecticut and the estates of non-domiciliaries if: Connecticut. This Q&A addresses state laws and The decedent last resided in Connecticut. customs that impact the process of an estate The decedent left real or tangible personal property located in proceeding, including the key statutes and rules Connecticut. related to estate proceedings, the different types The decedent maintained a bank account in Connecticut or any bank account of the decedent is located in Connecticut. of estate proceedings available in Connecticut, The decedent left evidence of other intangible personal property in and the processes for opening an estate, Connecticut (for example, stock certificates or bonds). appointing an estate fiduciary, administering Any executor or trustee named in the will resides in Connecticut or, in the case of a bank or trust company, has an office in the estate, handling creditor claims, and closing Connecticut. the estate. Any cause of action in favor of the decedent arose in Connecticut or any debtor of the decedent resides in Connecticut. (Conn. Gen. Stat. Ann. § 45a-287.) KEY STATUTES AND RULES A determination of domicile at the time of death of any deceased person is made by the Probate Court, but any finding of domicile 1. What are the state laws and rules that govern estate by the Probate Court is subject to a later determination of domicile proceedings? in connection with the Connecticut estate tax (Conn. -

Estate Planning Newsletter

estate planning newsletter spring 2012 hogefenton.com Our 2012 newsletter focuses on practical issues you or loved ones may face and (for once) includes no long article about taxes. Your preferences concerning end of life care are the most personal part of your planning, so we’ve included an article about some planning tools you may consider. Individuals considering serving as trustees or wrestling with choosing trustees should enjoy the article written from the first person perspective of a novice trustee. Our work with our firm’s robust family law practice led to a useful article on estate planning and divorce. Our discussion of taxes is brief, but important: 2012 is the final year for the high $5M lifetime estate, gift and generation-skipping tax exclusions. This is a “one-time offer” from Uncle Sam: the tax exemptions drop to $1M in 2013 under the current law, unless Congress changes the law again. The high exemptions and the expectation that asset values will increase present a unique opportunity for clients to make large wealth transfers to their families and reduce their future taxable estates. If you are considering significant wealth transfers, please talk to us soon. We expect the end of 2013 will be very busy for our team. © J.B. Handelsman/The New Yorker Collection/www.cartoonbank.com AHCDs, DNR Orders, Living Wills, POLSTs, …… We routinely recommend that each estate planning client complete an Advance Health What does it all mean? Care Directive (AHCD), appointing an agent to make health care decisions for the client if he is unable to make those decisions himself. -

Trust Law Implications of Proposed Regulatory Reform of Mutual Fund Governance Structures

Trust Law Implications of Proposed Regulatory Reform of Mutual Fund Governance Structures A Background Research Report to Concept Proposal 81-402 of the Canadian Securities Administrators Prepared by David P. Stevens Goodman and Carr LLP 200 King Street West, Suite 2300 Toronto, ON M5H 3W5 March 1, 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND ................................................................................1 1. INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................1 2. BACKGROUND .....................................................................................................4 II. THE MUTUAL FUND INDUSTRY ......................................................................................12 3. CURRENT STRUCTURES AND PRACTICES ..................................................12 Common Mutual Fund Structures .........................................................................12 The Importance of the Investor/Manager Relationship..........................................15 The Fiduciary Conflicts of the Manager ................................................................18 Classifications of Mutual Funds - The Legal Constitution ...................................21 4. REASONS FOR COMMON STRUCTURES ......................................................24 Taxation Reasons...................................................................................................25 Governance Reasons..............................................................................................29 -

Representations Involving Fiduciary Entities: Who Is the Client?

Fordham Law Review Volume 62 Issue 5 Article 15 1994 Representations Involving Fiduciary Entities: Who is the Client? Jeffrey N. Pennell Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jeffrey N. Pennell, Representations Involving Fiduciary Entities: Who is the Client?, 62 Fordham L. Rev. 1319 (1994). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol62/iss5/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Representations Involving Fiduciary Entities: Who is the Client? Cover Page Footnote Richard H. Clark Professor of Law, Emory University School of Law. This article is available in Fordham Law Review: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol62/iss5/15 REPRESENTATIONS INVOLVING FIDUCIARY ENTITIES: WHO IS THE CLIENT? JEFFREY N. PENNELL * A significant unresolved ethical issue that haunts attorneys who are engaged to assist in the administration of a fiduciary entity is: to whom do the attorney's duties and loyalties run, and with what ancillary or derivative obligations? In most situations this "who is the client" is- sue is of academic interest only, because the potential for a real conflict among the fiduciary, beneficiaries, and claimants such as creditors or dis- appointed heirs never ripens into a real controversy. But in a small per- centage of cases involving fiduciary administration the real and present issue is whether an attorney who is engaged to advise the administration represents the fiduciary who actually hired the attorney, the beneficiaries of the fiduciary entity, or the entity itself. -

Breach of Fiduciary Duty Claims

CLAIMS ARISING FROM A BREACH OF A FIDUCIARY DUTY This manuscript is intended to serve as a reference for judges who are handling civil cases involving legal claims arising from fiduciary or confidential relationships between the litigants. In many instances, these claims are labeled as constructive fraud claims. In the first section of this paper, the essential elements of these claims are discussed. The second section of this paper addresses particular relationships which may or may not constitute a fiduciary or confidential relationship. WHAT POLICIES ARE ADVANCED BY THIS BODY OF LAW Essentially, the law in this area seeks to prevent fraud and to protect individuals who are in a relatively vulnerable position. These policies are reflected in the following statements from North Carolina appellate courts: “Fraud, actual and constructive, is so varied in form many courts have refused to precisely define it, lest the definition itself be turned into an avenue of escape by the crafty and unscrupulous. Nevertheless, the legal principles that govern constructive fraud claims are well established. One is that a case of constructive fraud is established when proof is presented that a position of trust and confidence was taken advantage of to the hurt of the other.” Terry v. Terry, 302 N.C. 77, 273 S.E. 2d 674 (1981); Link v. Link, 278 N.C. 181, 179 S.E. 2d 697 (1971). “Any transaction between persons so situated is 'watched with extreme jealousy and solicitude; and if there is found the slightest trace of undue influence or unfair advantage, redress will be given to the injured party.'" See Eubanks v.