Trust Privacy Frances H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Dakota Vs. Minnesota Trust Law Desk Reference Guide

South Dakota vs. Minnesota Trust Law Desk Reference Guide Advantage South Dakota Minnesota For over 30 years, SD has been Like many states, MN has one of the best places to locate attempted to catch up to SD by a trust. A unique and active implementing the Uniform legislative trust committee, Trust Code. However, the Trust Location (Situs) favorable Legislature and difference is still clear and governor support continues to distinct, and the state does not rank SD as a top tier trust have the stability or support jurisdiction state; as verified by that SD enjoys from the industry leaders. government. In addition to many other taxes, MN taxes its trusts. In 2018, the There is no state personal, Fielding v. Commissioner of corporate, or fiduciary income Revenue decision highlighted tax, as well as no state tax on this major difference, holding State Taxes capital gains, dividends, that a trust set up as a MN trust interest, intangibles, or any may not need to stay a resident other income. This equates to trust for tax purposes for the NO state taxes on trust income. entire length of the trust (depending on circumstances). A Dynasty Trust has unlimited possibilities because there is no Rule Against Perpetuities MN has a Rule Against The Dynasty Trust - Legacy (abolished in 1983). Dynasty Perpetuities. By statute, all Trusts avoid federal estate and non-vested interests must vest Planning for Generations income taxation on trust assets (pass) 21 years after death of an because there is no forced asset individual or 90 years after its distribution and the bonus of creation. -

How Unclaimed Property Laws Impact Funds in Your Preneed Trust

BY WENDY RUSSELL WIENER We all recognize the benefit of general laws dealing with unclaimed property, which facilitate reuniting people with MISMATCHEDproperty they’ve lost track of – entirely M appropriate when the property is money in a bank account. But the op- eration of those laws on preneed trust funds is not entirely appropriate LAWS and can put trustees and licensees in an HOW UNCLAIMED impossible position. PROPERTY LAWS Let’s start by looking at the only two IMPACT FUNDS ways to fund a preneed contract. The first option is for the consumer to pay IN YOUR PRENEED the funeral home, which must then de- posit some or all of the money into trust. TRUST. The other option is for the consumer to purchase a life insurance policy; the same three circumstances – fulfillment, NOW THAT ACTION HAS BEEN TAKEN IN death benefit payable under that policy cancellation or default. SOME STATES, THEY'VE GONE ABOUT is assigned to the funeral home so that Thus, the trust funds are locked up the firm will receive some or all of the by both law and contract, and they can IT INCORRECTLY, AMENDING ONLY money upon the death of the preneed only be accessed when one of the three GENERAL UNCLAIMED PROPERTY LAWS contract beneficiary. conditions occur. WHILE IGNORING SPECIFIC PRENEED Only one of these funding mecha- Few states include, within their pre- nisms – insurance – is exempt from the need laws, direction to the funeral TRUST LAWS. BY DOING SO, STATES reach of the unclaimed property laws home or trustee on how to handle pre- HAVE LITERALLY ENACTED LAWS THAT in some states. -

Imperfect Gifts As Declarations of Trust: Unapologetic Anomaly Sarajane Love Rutgers University-Camden

Kentucky Law Journal Volume 67 | Issue 2 Article 3 1978 Imperfect Gifts as Declarations of Trust: Unapologetic Anomaly Sarajane Love Rutgers University-Camden Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Part of the Estates and Trusts Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Love, Sarajane (1978) "Imperfect Gifts as eD clarations of Trust: Unapologetic Anomaly," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 67 : Iss. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol67/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IMPERFECT GIFTS AS DECLARATIONS OF TRUST: AN UNAPOLOGETIC ANOMALY By SARAJANE LovE* One fundamental proposition is that, under a legal system recognizing the individualistic institution of private property and granting to the owner the power to determine his succes- sors in ownership, the general philosophy of the courts should favor giving effect to an intentional exercise of that power.' INTRODUCTION Ethel Yahuda was a widow who wished to give a library of Hebrew manuscripts collected by her and her late husband to the Hebrew University in Israel. She announced her gift at a public luncheon in Israel and upon her return to the United States began to catalogue and crate the collection for shipment to the university. Her intention to go forward with the gift was repeatedly expressed to friends and to the university. -

Fiduciary Roles in Your Estate Plan in Illinois WHAT IS a FIDUCIARY ROLE?

FIDUCIARY ROLES IN YOUR ESTATE IN ILLINOIS PLAN “A “fiduciary” role refers to a position of trust, often involving money or property that has been entrusted to the individual in the fiduciary role.” CURTIS J. FORD ILLINOIS ATTORNEY A number of important decisions must be made when you create your estate plan. While many of these decisions relate to the disposition of estate assets should you become incapacitated or die, some of the most important decisions you will need to make have nothing to do with assets. Instead, those decisions involve fulfilling fiduciary roles in your estate plan. All too often individuals are chosen to fill fiduciary roles within an estate plan without giving adequate thought to the choices. A better understanding of the various fiduciary roles within your estate plan and the importance of choosing the right person for the job may prevent you from making this mistake. 2 Fiduciary Roles in Your Estate Plan in Illinois www.nashbeanford.com WHAT IS A FIDUCIARY ROLE? A “fiduciary” role refers to a position of trust, often involving money or property that has been entrusted to the individual in the fiduciary role. A fiduciary must use the utmost care when handling money or assets entrusted to him or her because those assets are intended to be used for the benefit of a third party beneficiary. Furthermore, a fiduciary is expected to make prudent investment decisions and not take risks with assets unless specifically directed to do so by the person who appointed the fiduciary. In short, a fiduciary should be more careful with assets entrusted to his or her care than the fiduciary would be with his or her own assets. -

Southampton Student Law Review 2014 Volume 4, Issue 1

Southampton Student Law Review 2014 volume 4, issue 1 1 Southampton Student Law Review Southampton Law School Published in the United Kingdom By the Southampton Student Law Review Southampton Law School University of Southampton SO17 1BJ In affiliation with the University of Southampton, Southampton Law School All rights reserved. Copyright© 2014 University of Southampton. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, or stored in any retrieval system of any nature, without the prior, express written permission of the Southampton Student Law Review and the author, to whom all requests to reproduce copyright material should be directed, in writing. The views expressed by the contributors are not necessarily those of the Editors of the Southampton Student Law Review. Whilst every effort has been made to ensure that the information contained in this journal is correct, the Editors do not accept any responsibility for any errors or omissions, or for any resulting consequences. © 2014 Southampton Student Law Review www.southampton.ac.uk/law/lawreview ISSN 2047 - 1017 This volume should be cited (2014) 4(1) S.S.L.R. Editorial Board 2014 Editors-in-Chief Elizabeth Herbert Ida Petretta Editorial Board Neil Brown Louise Cheung Dingjing (James) Huang Ebenezer Laryea Henry Pearce Viktor Weber Acknowledgements The Editors wish to thank our academic advisor Professor Oren Ben-Dor for his advice, commitment and support The Editors also wish to thank all members -

The Early Autumn Edition of Trust Espeaking. Inside We Have What We Hope Are Interesting and Useful Articles. Trusts

ISSUE 16 | AUTUMN 2013 GREG KELLY LAW LIMITED Level 6 Change House, 150 Featherston Street, Wellington | PO Box 25-243, Panama St, Wellington 6146, New Zealand Ph: 04 498-8500 | Fax: 04 499-5193 | E-mail: [email protected] | www.trustlaw.co.nz Welcome to the early Autumn edition of Trust eSpeaking. Inside we have what we hope are interesting and useful articles. If you would like to talk further about any of the material in this newsletter, or about trusts in general, then please don’t hesitate to contact us. Inside: Trusts and Avoidance of Rest Home Fees All quite tricky It was very common in the 1990s for New Zealanders to set up discretionary family trusts in the hope that by putting assets in the name of a trust, they could qualify for rest home subsidies in the event that they were required to go into rest home care. This certainly worked for a number of years. Things have changed, however, and this article looks at a recent case that challenged that proposition… CONTINUE READING Right to Decide About Funeral and Burial Still some uncertainties Arguments over where the late Mr James Takamore should be buried have led to a long-running legal dispute. Now the Supreme Court has spoken, but its decision in Takamore v Clarke leaves some questions unanswered… CONTINUE READING Law Commission’s Key Proposals for New Trusts Legislation Whilst the Law Commission is reviewing trust law, we’ve undertaken to keep you up-to-date with its recommendations; which is much easier than you having to read the 300+ pages of the Commission’s report… CONTINUE READING If you do not want to receive this newsletter, please unsubscribe. -

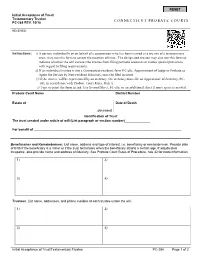

Initial Acceptance of Trust/ Testamentary Trustee PC-284 REV. 10/18

Initial Acceptance of Trust/ Testamentary Trustee CONNECTICUT PROBATE COURTS PC-284 REV. 10/18 RECEIVED: Instructions: 1) A person, individually or on behalf of a corporation who has been named as a trustee of a testamentary trust, may use this form to accept the position of trust. The designated trustee may also use this form to indicate whether the will excuses the trustee from filing periodic accounts or makes special provisions with regard to filing requirements. 2) If an individual trustee is not a Connecticut resident, form PC-482, Appointment of Judge or Probate as Agent for Service by Non-resident Fiduciary, must be filed in court. 3) If the trustee will be represented by an attorney, the attorney must file an Appearance of Attorney, PC- 183, in accordance with Probate Court Rules, Rule 5. 4) Type or print the form in ink. Use Second Sheet, PC-180, or an additional sheet if more space is needed. Probate Court Name District Number Estate of Date of Death ,deceased Identification of Trust The trust created under article of will (List paragraph or section number)______________ For benefit of _________________________________________________________________________________ Beneficiaries and Remaindermen: List name, address and type of interest, i.e, beneficiary or remainderman. Provide date of birth if the beneficiary is a minor or if the trust terminates when the beneficiary attains a certain age. If adjudicated incapable, also provide name and address of fiduciary. See Probate Court Rules of Procedure, rule 32 for more information. 1) 2) 3) 4) Trustees: List name, addresses, and phone number of each trustee under the will. -

Trust Administration Guidelines for Trustees

LAW OFFICES OF MICHAEL E. GRAHAM 10343 HIGH STREET, SUITE ONE TRUCKEE, CALIFORNIA 96161-0116 TELEPHONE 530.587.1177 P FACSIMILE 530.587.0707 MICHAEL E. GRAHAM † [email protected] TRUST ADMINISTRATION GUIDELINES FOR TRUSTEES I. INTRODUCTION The average person has had little experience dealing with trusts and often has many questions upon becoming a Trustee for the first time. Since you will be the Trustee of a Trust, the purpose of this memo is to try to anticipate your questions by providing a general overview of how Trusts work and your duties and responsibilities as Trustee. Through our experience in helping people administer trusts, we have found that many individuals have unrealistic expectations concerning the way living trusts operate following a death. It is true that a living trust in many cases drastically reduces the costs and delays involved in passing on assets at death. A living trust accomplishes this feat by avoiding probate. However, even without a probate, many administrative chores have to be completed, legal documents prepared, taxes returns filed, and other matters that take time and cost money. II. TRUSTS IN GENERAL A. What is a Trust? A trust is a legal relationship, usually evidenced by a written document called a "Declaration of Trust" or "Trust Agreement," whereby one person, called the "Trustor," transfers property to another person, called the "Trustee," who holds the property for the benefit of another person, called the "Beneficiary." The same person may occupy more than one position at a time. For example, in the typical living trust, as long as the Trustor is alive, the Trustor is also the Trustee and Beneficiary. -

Probate: Connecticut

Resource ID: w-009-4550 Probate: Connecticut JESSIE A. GILBERT, SUSAN HUFFARD, AND KATHERINE A. MCALLISTER, CUMMINGS & LOCKWOOD LLC WITH PRACTICAL LAW TRUSTS & ESTATES Search the Resource ID numbers in blue on Westlaw for more. A Q&A guide to the laws of probate in Courts have jurisdiction over the estates of decedents domiciled in Connecticut and the estates of non-domiciliaries if: Connecticut. This Q&A addresses state laws and The decedent last resided in Connecticut. customs that impact the process of an estate The decedent left real or tangible personal property located in proceeding, including the key statutes and rules Connecticut. related to estate proceedings, the different types The decedent maintained a bank account in Connecticut or any bank account of the decedent is located in Connecticut. of estate proceedings available in Connecticut, The decedent left evidence of other intangible personal property in and the processes for opening an estate, Connecticut (for example, stock certificates or bonds). appointing an estate fiduciary, administering Any executor or trustee named in the will resides in Connecticut or, in the case of a bank or trust company, has an office in the estate, handling creditor claims, and closing Connecticut. the estate. Any cause of action in favor of the decedent arose in Connecticut or any debtor of the decedent resides in Connecticut. (Conn. Gen. Stat. Ann. § 45a-287.) KEY STATUTES AND RULES A determination of domicile at the time of death of any deceased person is made by the Probate Court, but any finding of domicile 1. What are the state laws and rules that govern estate by the Probate Court is subject to a later determination of domicile proceedings? in connection with the Connecticut estate tax (Conn. -

Michigan Probate & Estate Planning Journal Winter 2016

MICHIGAN PROBATE & ESTATE PLANNING JOURNAL TABLE OF CONTENTS Vol. 36 M Winter 2016 M No. 1 Featured Articles: From the Probate Litigation Desk: Obser- vations on Undue Influence David L.J.M. Skidmore .......................... 3 New Year’s Resolutions for Trustees and Beneficiaries: Ten Fiduciary Income Tax Planning Considerations Raj A. Malviya and Jonathan K. Beer .. 13 Two Matters Improperly Decided By the Michigan Court of Appeals: In Re Estate of Sabry Mohammad Attia and In Re Estate of James V Ward Alan A. May ......................................... 27 Conflicts of Interest in Estate Planning and Litigation (Or “How Many Hats Are Too Many?”) Robert S. Zawideh ............................... 31 Long-Awaited Probate Appeals Legisla- tion Brings Uniformity and Efficiency Liisa R. Speaker ................................... 36 Pets Put Their Trust in Us—Put Them in the Trust: Default Provisions That Protect Pets Rebecca Wrock .................................... 41 Why Would You Worry About Proposed Regulations to Section 2704? Lorraine F. New ................................... 45 STATE BAR OF MICHIGAN PROBATE AND ESTATE PLANNING SECTION Subscription Information The Michigan Probate and Estate Planning Journal is Michigan Probate and Estate Planning Journal published three times a year by the Probate and Estate M M Planning Section of the State Bar of Michigan, with the Vol. 36 Winter 2016 No. 1 cooperation of the Institute of Continuing Legal Education, and is sent electronically to all members of the Section. Lawyers newly admitted to the State Bar automatically become members of the Section for two years following their date of TABLE OF CONTENTS admission. Members of the State Bar, as well as law school students, may become members of the Section by paying annual dues of $35. -

Estate Planning Newsletter

estate planning newsletter spring 2012 hogefenton.com Our 2012 newsletter focuses on practical issues you or loved ones may face and (for once) includes no long article about taxes. Your preferences concerning end of life care are the most personal part of your planning, so we’ve included an article about some planning tools you may consider. Individuals considering serving as trustees or wrestling with choosing trustees should enjoy the article written from the first person perspective of a novice trustee. Our work with our firm’s robust family law practice led to a useful article on estate planning and divorce. Our discussion of taxes is brief, but important: 2012 is the final year for the high $5M lifetime estate, gift and generation-skipping tax exclusions. This is a “one-time offer” from Uncle Sam: the tax exemptions drop to $1M in 2013 under the current law, unless Congress changes the law again. The high exemptions and the expectation that asset values will increase present a unique opportunity for clients to make large wealth transfers to their families and reduce their future taxable estates. If you are considering significant wealth transfers, please talk to us soon. We expect the end of 2013 will be very busy for our team. © J.B. Handelsman/The New Yorker Collection/www.cartoonbank.com AHCDs, DNR Orders, Living Wills, POLSTs, …… We routinely recommend that each estate planning client complete an Advance Health What does it all mean? Care Directive (AHCD), appointing an agent to make health care decisions for the client if he is unable to make those decisions himself. -

The Functions of Trust Law: a Comparative Legal and Economic Analysis, 73 N.Y.U

University of California, Hastings College of the Law UC Hastings Scholarship Repository Faculty Scholarship 1998 The uncF tions of Trust Law: A Comparative Legal and Economic Analysis Ugo Mattei UC Hastings College of the Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Estates and Trusts Commons Recommended Citation Ugo Mattei, The Functions of Trust Law: A Comparative Legal and Economic Analysis, 73 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 434 (1998). Available at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/faculty_scholarship/529 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Faculty Publications UC Hastings College of the Law Library Mattei Ugo Author: Ugo Mattei Source: New York University Law Review Citation: 73 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 434 (1998). Title: The Functions of Trust Law: A Comparative Legal and Economic Analysis Originally published in NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW. This article is reprinted with permission from NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW and New York University School of Law. THE FUNCTIONS OF TRUST LAW: A COMPARATIVE LEGAL AND ECONOMIC ANALYSIS HENRY HANSMANN* UGO MATTEI** In this Article, ProfessorsHenry Hansmann and Ugo Mattei analyze the functions served by the law of trusts and ask, first, whether the basic tools of contract and agency law could fulfill the same functions and, second, whether trust law provides benefits that are not provided by the law of corporations.