Building Trust Between the Police and the Citizens They Serve

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ICO – Privacy Impact Assessment Handbook

Using this handbook Part 1 – Background information Part 2 – The PIA process Appendix 1 – The PIA screening questions Appendix 2 – Data protection compliance checklist template Appendix 3 – PECR compliance checklist template Appendix 4 – Privacy strategies Using this handbook Back to ICO homepage Advice on using this handbook Because organisations vary greatly in size, the extent to which their activities intrude on privacy, and their experience in dealing with privacy issues makes it difficult to write a ‘one size fits all’ guide. The purpose of this handbook is to be comprehensive. It is important to note now that not all of the information provided in this handbook will be relevant to every project that will be assessed. The handbook is split into two distinct parts. Part I (Chapters I and II) are designed to give background information on the privacy impact assessment (PIA) process and privacy. Part II is a practical “how to” guide on the PIA process. The handbook’s structure is intended to enable a reader who is knowledgeable about privacy to quickly start working on the PIA. Background information on privacy and PIAs is provided for other readers who would like some general information prior to starting the PIA process. It is also important to note that some of the recommendations in this handbook may overlap with work which is being done to satisfy other requirements, such as information security and assurance, other forms of impact assessment or requirements to carry out broader consultations during the development of a project. A PIA does not have to be conducted as a completely separate exercise and it can be useful to consider privacy issues in a broader policy context. -

The Honorable John F. Kelly January 30, 2017 Secretary Department of Homeland Security 3801 Nebraska Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20036

The Honorable John F. Kelly January 30, 2017 Secretary Department of Homeland Security 3801 Nebraska Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20036 The Honorable Sally Yates Acting Attorney General Department of Justice 950 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20530 The Honorable Thomas A. Shannon Acting Secretary Department of State 2201 C Street, NW Washington, DC 20520 Secretary Kelly, Acting Attorney General Yates, Acting Secretary Shannon: As former cabinet Secretaries, senior government officials, diplomats, military service members and intelligence community professionals who have served in the Bush and Obama administrations, we, the undersigned, have worked for many years to make America strong and our homeland secure. Therefore, we are writing to you to express our deep concern with President Trump’s recent Executive Order directed at the immigration system, refugees and visitors to this country. This Order not only jeopardizes tens of thousands of lives, it has caused a crisis right here in America and will do long-term damage to our national security. In the middle of the night, just as we were beginning our nation’s commemoration of the Holocaust, dozens of refugees onboard flights to the United States and thousands of visitors were swept up in an Order of unprecedented scope, apparently with little to no oversight or input from national security professionals. Individuals, who have passed through multiple rounds of robust security vetting, including just before their departure, were detained, some reportedly without access to lawyers, right here in U.S. airports. They include not only women and children whose lives have been upended by actual radical terrorists, but brave individuals who put their own lives on the line and worked side-by-side with our men and women in uniform in Iraq now fighting against ISIL. -

Spotlight On… Protection of Sensitive Data Including Personal Information

Spotlight On… Protection of Sensitive Data including Personal Information Purpose On Sept. 7, 2017 media reports indicated that a large American credit score bureau had been breached, exposing the personal information of millions of consumers in the U.S. and in the U.K. and potentially affecting 8,000 individuals in Canada. On November 28, 2017 the Canadian arm of this U.S. company posted information on its website indicating that an additional 11,670 Canadians had been affected by the breach, bringing the total number of Canadians affected to about 19,000. In response to CCIRC partner questions concerning this event, this product provides information on what organizations can do to reduce the risk of sensitive data, such as personal information, being exfiltrated from their organization. Information in this note includes: . The Canadian statutory definitions of personal information . Upcoming regulatory changes to data breach reporting in Canada . Examples of reported breaches of Canadian personal information . Tactics, techniques, and procedures employed to target Canadian personal information . Tips for safeguarding sensitive information . Advice from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) for individuals who believe their personal information may have been compromised What is “Personal Information”? According to the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (OPC), these are the statutory provisions relevant to the meaning of “Personal Information” in Canada: Section 2(1) of the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents -

Congressional Record—Senate S9304

S9304 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE September 14, 2009 table, but this man is one of the great- the principal symptom of this adminis- Let me take my concerns one by one. est humanitarians who have ever lived. tration’s 8-month record of too many Article I of the Constitution of the He dedicated his life to the develop- Washington takeovers. We have an United States gives to the Congress the ment of scientific breakthroughs in AIDS czar, an auto recovery czar, a appropriations power and sets up, in order to ease malnutrition and famine border czar, and a California water articles II and III, the executive and ju- all over the world. czar. We have a car czar, a central re- dicial branches, a system of checks and One of Dr. Borlaug’s latest efforts gion czar, and a domestic violence czar. balances to make sure no one branch of began in the early 1980s. There wasn’t There is an economic czar, an energy the Federal Government runs away anything in the Nobel armada of prizes and environment czar, a faith-based with the government. Senator ROBERT that represented agriculture, which is czar and a Great Lakes czar. The list BYRD, the President pro tempore of the why he received the Peace Prize for goes on, up to 32 or 34. One of these, for Senate, wrote a letter to President recognition of his research in agri- example, is the pay czar, Mr. Kenneth Obama on February 23. Senator BYRD, culture, and so Dr. Borlaug thought Feinberg, the Treasury Department’s who is often called the Constitutional there ought to be an annual award for Special Master for Compensation. -

Government Officials (National, State, Local)

11/6/13 Government Officials (National, State, Local) Alabama Congressional Delegation Senate Jeff Sessions (http://www.sessions.senate.gov/public/) (R): 335 Russell Senate Office Building, Washington, D.C. 20510-0104 Telephone: 202-224-4124 Huntsville Office: 200 Clinton Avenue NW, Regions Center, Suite 802, Huntsville, AL 35801 -4932 Main: (256) 533-0979 Fax: (256) 533-0745 Richard Shelby (http://shelby.senate.gov/public/)( R): 304 Russell Senate Office Building, Washington, D.C. 20510-0103 Telephone: 202-224-5744 Huntsville Office: 1000 Glenn Hearn Blvd. Box 20127, Huntsville, AL 35824 Telephone: (256) 772-0460 House of Representatives http://www.house.gov/ General address of all Representatives: U.S. House of Representatives, Washington, D.C. 20515 District 1: Jo Bonner ( R )http://bonner.house.gov/ District 2: Martha Roby ( R ) http://roby.house.gov/ District 3: Mike Rogers ( R )http://mike-rogers.house.gov/ District 4: Robert Aderholt ( R ) http://aderholt.house.gov/ District 5: Mo Brooks ( R ) http://brooks.house.gov/ Washington office, Huntsville office Washington Office (http://brooks.house.gov/contact-me/): 1230 Longworth HOB Washington, DC 20515 Washington telephone: (202)225-4801 Huntsville Office (http://brooks.house.gov/contact-me/) 2101 W. Clinton Avenue, Suite 302 Huntsville, AL 35805 Huntsville telephone: (256)551-0190 District 6: Spencer Bachus ( R ) (http://bachus.house.gov/) District 7: Terri Sewell ( D ) (https://sewell.house.gov/contact-me) 11/6/13 Federal Officials President: Barrack Hussein Obama II (http://www.whitehouse.gov/) Born: August 4, 1961, in Honolulu, HI Address: The White House, 1600 Pennsylvania Ave. NW, Washington, D.C. 20500 Vice-President: Joseph Robinette Biden, Jr. -

Fiduciary Roles in Your Estate Plan in Illinois WHAT IS a FIDUCIARY ROLE?

FIDUCIARY ROLES IN YOUR ESTATE IN ILLINOIS PLAN “A “fiduciary” role refers to a position of trust, often involving money or property that has been entrusted to the individual in the fiduciary role.” CURTIS J. FORD ILLINOIS ATTORNEY A number of important decisions must be made when you create your estate plan. While many of these decisions relate to the disposition of estate assets should you become incapacitated or die, some of the most important decisions you will need to make have nothing to do with assets. Instead, those decisions involve fulfilling fiduciary roles in your estate plan. All too often individuals are chosen to fill fiduciary roles within an estate plan without giving adequate thought to the choices. A better understanding of the various fiduciary roles within your estate plan and the importance of choosing the right person for the job may prevent you from making this mistake. 2 Fiduciary Roles in Your Estate Plan in Illinois www.nashbeanford.com WHAT IS A FIDUCIARY ROLE? A “fiduciary” role refers to a position of trust, often involving money or property that has been entrusted to the individual in the fiduciary role. A fiduciary must use the utmost care when handling money or assets entrusted to him or her because those assets are intended to be used for the benefit of a third party beneficiary. Furthermore, a fiduciary is expected to make prudent investment decisions and not take risks with assets unless specifically directed to do so by the person who appointed the fiduciary. In short, a fiduciary should be more careful with assets entrusted to his or her care than the fiduciary would be with his or her own assets. -

National Prevention Strategy AMERICA’S PLAN for BETTER HEALTH and WELLNESS

National Prevention Strategy AMERICA’S PLAN FOR BETTER HEALTH AND WELLNESS June 2011 National Prevention, Health Promotion and Public Health Council For more information about the National Prevention Strategy, go to: http://www.healthcare.gov/center/councils/nphpphc. OFFICE of the SURGEON GENERAL 5600 Fishers Lane Room 18-66 Rockville, MD 20857 email: [email protected] Suggested citation: National Prevention Council, National Prevention Strategy, Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General, 2011. National Prevention Strategy America’s Plan for Better Health and Wellness June 16, 2011 2 National Prevention Message from the Chair of the National Prevention,Strategy Health Promotion, and Public Health Council As U.S. Surgeon General and Chair of the National Prevention, Health Promotion, and Public Health Council (National Prevention Council), I am honored to present the nation’s first ever National Prevention and Health Promotion Strategy (National Prevention Strategy). This strategy is a critical component of the Affordable Care Act, and it provides an opportunity for us to become a more healthy and fit nation. The National Prevention Council comprises 17 heads of departments, agencies, and offices across the Federal government who are committed to promoting prevention and wellness. The Council provides the leadership necessary to engage not only the federal government but a diverse array of stakeholders, from state and local policy makers, to business leaders, to individuals, their families and communities, to champion the policies and programs needed to ensure the health of Americans prospers. With guidance from the public and the Advisory Group on Prevention, Health Promotion, and Integrative and Public Health, the National Prevention Council developed this Strategy. -

Annual Privacy Report

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE ANNUAL PRIVACY REPORT THE CHIEF PRIVACY AND CIVIL LIBERTIES OFFICER AND THE OFFICE OF PRIVACY AND CIVIL LIBERTIES OCTOBER 1, 2016 – SEPTEMBER 30, 2020 1 (MULTI) ANNUAL PRIVACY REPORT MESSAGE FROM THE CHIEF PRIVACY AND CIVIL LIBERTIES OFFICER I am pleased to present the Department of Justice’s (Department or DOJ) Annual Privacy Report, describing the operations and activities of the Chief Privacy and Civil Liberties Officer (CPCLO) and the Office of Privacy and Civil Liberties (OPCL), in accordance with Section 1174 of the Violence Against Women and Department of Justice Reauthorization Act of 2005. This report covers the period from October 1, 2016, through September 30, 2020. The Department’s privacy program is supported by a team of dedicated privacy professionals who strive to build a culture and understanding of privacy within the complex and diverse mission work of the Department. The work of the Department’s privacy team is evident in the care, consideration, and dialogue about privacy that is incorporated in the daily operations of the Department. During this reporting period, there has been an evolving landscape of technological development and advancement in areas such as artificial intelligence, biometrics, complex data flows, and an increase in the number of cyber security events resulting in significant impacts to the privacy of individuals. Thus, the CPCLO and OPCL have developed new policies and guidance to assist the Department with navigating these areas, some of which include the following: -

Filling Advice and Consent Positions at the Outset of a New Administration

Filling Advice and Consent Positions at the Outset of a New Administration -name redacted- Analyst in American National Government Maureen Bearden Information Research Specialist April 1, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov R40119 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Filling Advice and Consent Positions at the Outset of a New Administration Summary In its 2004 report, the 9/11 Commission identified what it perceived were shortcomings in the appointment process during presidential transitions. The report asserted that delays in filling top executive branch leadership positions, such as those experienced during the 2000-2001 transition, could compromise national security policymaking in the early months of a new Administration. Although the unique circumstances of the 2000 presidential race truncated the ensuing transition period, the commission’s observations could be applied to other recent transitions; lengthy appointment processes during presidential transitions, particularly between those of different political parties, have been of concern to observers for more than 20 years. The process is likely to develop a bottleneck during this time, even under the best of circumstances, due to the large number of candidates who must be selected, vetted, and, in the case of positions filled through appointment by the President with the advice and consent of the Senate (PAS positions), considered by that body. The appointment process has three stages: selection and vetting, Senate consideration, and presidential appointment. Congress has taken steps to accelerate appointments during presidential transitions. In recent decades, Senate committees have provided for pre-nomination consideration of Cabinet-level nominations; examples of such actions are provided in this report. -

The United States Government Manual 2009/2010

The United States Government Manual 2009/2010 Office of the Federal Register National Archives and Records Administration The artwork used in creating this cover are derivatives of two pieces of original artwork created by and copyrighted 2003 by Coordination/Art Director: Errol M. Beard, Artwork by: Craig S. Holmes specifically to commemorate the National Archives Building Rededication celebration held September 15-19, 2003. See Archives Store for prints of these images. VerDate Nov 24 2008 15:39 Oct 26, 2009 Jkt 217558 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6996 Sfmt 6996 M:\GOVMAN\217558\217558.000 APPS06 PsN: 217558 dkrause on GSDDPC29 with $$_JOB Revised September 15, 2009 Raymond A. Mosley, Director of the Federal Register. Adrienne C. Thomas, Acting Archivist of the United States. On the cover: This edition of The United States Government Manual marks the 75th anniversary of the National Archives and celebrates its important mission to ensure access to the essential documentation of Americans’ rights and the actions of their Government. The cover displays an image of the Rotunda and the Declaration Mural, one of the 1936 Faulkner Murals in the Rotunda at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) Building in Washington, DC. The National Archives Rotunda is the permanent home of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution of the United States, and the Bill of Rights. These three documents, known collectively as the Charters of Freeedom, have secured the the rights of the American people for more than two and a quarter centuries. In 2003, the National Archives completed a massive restoration effort that included conserving the parchment of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights, and re-encasing the documents in state-of-the-art containers. -

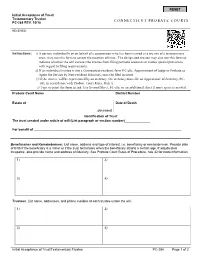

Initial Acceptance of Trust/ Testamentary Trustee PC-284 REV. 10/18

Initial Acceptance of Trust/ Testamentary Trustee CONNECTICUT PROBATE COURTS PC-284 REV. 10/18 RECEIVED: Instructions: 1) A person, individually or on behalf of a corporation who has been named as a trustee of a testamentary trust, may use this form to accept the position of trust. The designated trustee may also use this form to indicate whether the will excuses the trustee from filing periodic accounts or makes special provisions with regard to filing requirements. 2) If an individual trustee is not a Connecticut resident, form PC-482, Appointment of Judge or Probate as Agent for Service by Non-resident Fiduciary, must be filed in court. 3) If the trustee will be represented by an attorney, the attorney must file an Appearance of Attorney, PC- 183, in accordance with Probate Court Rules, Rule 5. 4) Type or print the form in ink. Use Second Sheet, PC-180, or an additional sheet if more space is needed. Probate Court Name District Number Estate of Date of Death ,deceased Identification of Trust The trust created under article of will (List paragraph or section number)______________ For benefit of _________________________________________________________________________________ Beneficiaries and Remaindermen: List name, address and type of interest, i.e, beneficiary or remainderman. Provide date of birth if the beneficiary is a minor or if the trust terminates when the beneficiary attains a certain age. If adjudicated incapable, also provide name and address of fiduciary. See Probate Court Rules of Procedure, rule 32 for more information. 1) 2) 3) 4) Trustees: List name, addresses, and phone number of each trustee under the will. -

Trust Administration Guidelines for Trustees

LAW OFFICES OF MICHAEL E. GRAHAM 10343 HIGH STREET, SUITE ONE TRUCKEE, CALIFORNIA 96161-0116 TELEPHONE 530.587.1177 P FACSIMILE 530.587.0707 MICHAEL E. GRAHAM † [email protected] TRUST ADMINISTRATION GUIDELINES FOR TRUSTEES I. INTRODUCTION The average person has had little experience dealing with trusts and often has many questions upon becoming a Trustee for the first time. Since you will be the Trustee of a Trust, the purpose of this memo is to try to anticipate your questions by providing a general overview of how Trusts work and your duties and responsibilities as Trustee. Through our experience in helping people administer trusts, we have found that many individuals have unrealistic expectations concerning the way living trusts operate following a death. It is true that a living trust in many cases drastically reduces the costs and delays involved in passing on assets at death. A living trust accomplishes this feat by avoiding probate. However, even without a probate, many administrative chores have to be completed, legal documents prepared, taxes returns filed, and other matters that take time and cost money. II. TRUSTS IN GENERAL A. What is a Trust? A trust is a legal relationship, usually evidenced by a written document called a "Declaration of Trust" or "Trust Agreement," whereby one person, called the "Trustor," transfers property to another person, called the "Trustee," who holds the property for the benefit of another person, called the "Beneficiary." The same person may occupy more than one position at a time. For example, in the typical living trust, as long as the Trustor is alive, the Trustor is also the Trustee and Beneficiary.