Gazprom: Gas Giant Under Strain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Killing of William Browder

THE KILLING OF WILLIAM BROWDER THE KILLING OF WILLIAM BROWDER Bill Browder, the fa lse crusader for justice and human rights and the self - styled No. 1 enemy of Vladimir Putin has perpetrated a brazen and dangerous deception upon the Weste rn world. This book traces the anatomy of this deception, unmasking the powerful forces that are pushing the West ern world toward yet another great war with Russia. ALEX KRAINER EQUILIBRIUM MONACO First published in Monaco in 20 17 Copyright © 201 7 by Alex Krainer ISBN 978 - 2 - 9556923 - 2 - 5 Material contained in this book may be reproduced with permission from its author and/or publisher, except for attributed brief quotations Cover page design, content editing a nd copy editing by Alex Krainer. Set in Times New Roman, book title in Imprint MT shadow To the people of Russia and the United States wh o together, hold the keys to the future of humanity. Enlighten the people generally, and tyranny and oppressions of body and mind will vanish like the evil spirits at the dawn of day. Thomas Jefferson Table of Contents 1. Bill Browder and I ................................ ................................ ............... 1 Browder’s 2005 presentation in Monaco ................................ .............. 2 Harvard club presentation in 2010 ................................ ........................ 3 Ru ssophobia and Putin - bashing in the West ................................ ......... 4 Red notice ................................ ................................ ............................ 6 Reading -

NOVATEK RS Presentation

“Harnessing the Energy of the Far North” Mark Gyetvay, Deputy Chairman of the Management Board Alexander Palivoda, Head of Investor Relations Goldman Sachs Global Natural Resources Conference London 11-12 November 2015 Forward-Looking Statements Certain statements in this presentation are not historical facts and are “forward-looking”. Examples of such forward-looking statements include, but are not limited to: – projections or expectations of revenues, income (or loss), earnings (or loss) per share, dividends, capital structure or other financial items or ratios; – statements of our plans, objectives or goals, including those related to products or services; – statements of future economic performance; and – statements of assumptions underlying such statements Words such as “believes”, “anticipates”, “expects”, “estimates”, “intends”, “plans”, “outlook” and similar expressions are intended to identify forward-looking statements but are not the exclusive means of identifying such statements By their very nature, forward-looking statements involve inherent risks and uncertainties, both general and specific, and risks exist that the predictions, forecasts, projections and other forward-looking statements will not be achieved. You should be aware that a number of important factors could cause actual results to differ materially from the plans, objectives, expectations, estimates and intentions expressed in such forward-looking statements When relying on forward-looking statements, you should carefully consider the foregoing factors and other uncertainties and events, especially in light of the political, economic, social and legal environment in which we operate. Such forward-looking statements speak only as of the date on which they are made, and we do not undertake any obligation to update or revise any of them, whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise. -

The Russia You Never Met

The Russia You Never Met MATT BIVENS AND JONAS BERNSTEIN fter staggering to reelection in summer 1996, President Boris Yeltsin A announced what had long been obvious: that he had a bad heart and needed surgery. Then he disappeared from view, leaving his prime minister, Viktor Cher- nomyrdin, and his chief of staff, Anatoly Chubais, to mind the Kremlin. For the next few months, Russians would tune in the morning news to learn if the presi- dent was still alive. Evenings they would tune in Chubais and Chernomyrdin to hear about a national emergency—no one was paying their taxes. Summer turned to autumn, but as Yeltsin’s by-pass operation approached, strange things began to happen. Chubais and Chernomyrdin suddenly announced the creation of a new body, the Cheka, to help the government collect taxes. In Lenin’s day, the Cheka was the secret police force—the forerunner of the KGB— that, among other things, forcibly wrested food and money from the peasantry and drove some of them into collective farms or concentration camps. Chubais made no apologies, saying that he had chosen such a historically weighted name to communicate the seriousness of the tax emergency.1 Western governments nod- ded their collective heads in solemn agreement. The International Monetary Fund and the World Bank both confirmed that Russia was experiencing a tax collec- tion emergency and insisted that serious steps be taken.2 Never mind that the Russian government had been granting enormous tax breaks to the politically connected, including billions to Chernomyrdin’s favorite, Gazprom, the natural gas monopoly,3 and around $1 billion to Chubais’s favorite, Uneximbank,4 never mind the horrendous corruption that had been bleeding the treasury dry for years, or the nihilistic and pointless (and expensive) destruction of Chechnya. -

Information on IRC – R.O.S.T., the Registrar of the Company and the Acting Ballot Committee of MMC Norilsk Nickel

Information on IRC – R.O.S.T., the registrar of the Company and the acting Ballot Committee of MMC Norilsk Nickel IRC – R.O.S.T. (former R.O.S.T. Registrar merged with Independent Registrar Company in February 2019) was established in 1996. In 2003–2015, Independent Registrar Company was a member of Computershare Group, a global leader in registrar and transfer agency services. In July 2015, IRC changed its ownership to pass into the control of a group of independent Russian investors. In December 2016, R.O.S.T. Registrar and Independent Registrar Company, both owned by the same group of independent investors, formed IRC – R.O.S.T. Group of Companies. In 2018, Saint Petersburg Central Registrar joined the Group. In February 2019, Independent Registrar Company merged with IRC – R.O.S.T. Ultimate beneficiaries of IRC – R.O.S.T. Group are individuals with a strong background in business management and stock markets. No beneficiary holds a blocking stake in the Group. In accordance with indefinite License No. 045-13976-000001, IRC – R.O.S.T. keeps records of holders of registered securities. Services offered by IRC – R.O.S.T. to its clients include: › Records of shareholders, interestholders, bondholders, holders of mortgage participation certificates, lenders, and joint property owners › Meetings of shareholders, joint owners, lenders, company members, etc. › Electronic voting › Postal and electronic mailing › Corporate consulting › Buyback of securities, including payments for securities repurchased › Proxy solicitation › Call centre services › Depositary and brokerage, including escrow agent services IRC – R.O.S.T. Group invests a lot in development of proprietary high-tech solutions, e.g. -

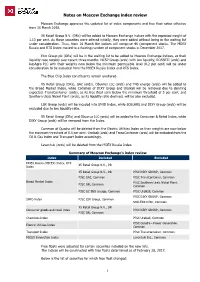

Notes on Moscow Exchange Index Review

Notes on Moscow Exchange index review Moscow Exchange approves the updated list of index components and free float ratios effective from 16 March 2018. X5 Retail Group N.V. (DRs) will be added to Moscow Exchange indices with the expected weight of 1.13 per cent. As these securities were offered initially, they were added without being in the waiting list under consideration. Thus, from 16 March the indices will comprise 46 (component stocks. The MOEX Russia and RTS Index moved to a floating number of component stocks in December 2017. En+ Group plc (DRs) will be in the waiting list to be added to Moscow Exchange indices, as their liquidity rose notably over recent three months. NCSP Group (ords) with low liquidity, ROSSETI (ords) and RosAgro PLC with their weights now below the minimum permissible level (0.2 per cent) will be under consideration to be excluded from the MOEX Russia Index and RTS Index. The Blue Chip Index constituents remain unaltered. X5 Retail Group (DRs), GAZ (ords), Obuvrus LLC (ords) and TNS energo (ords) will be added to the Broad Market Index, while Common of DIXY Group and Uralkali will be removed due to delisting expected. TransContainer (ords), as its free float sank below the minimum threshold of 5 per cent, and Southern Urals Nickel Plant (ords), as its liquidity ratio declined, will be also excluded. LSR Group (ords) will be incuded into SMID Index, while SOLLERS and DIXY Group (ords) will be excluded due to low liquidity ratio. X5 Retail Group (DRs) and Obuvrus LLC (ords) will be added to the Consumer & Retail Index, while DIXY Group (ords) will be removed from the Index. -

Exploration and Production

2006-2009 Triennium Work Report October 2009 WORKING COMMITTEE 1: EXPLORATION AND PRODUCTION Chair: Vladimir Yakushev Russia 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction SG 1.1 “Remaining conventional world gas resources and technological challenges for their development” report SG 1.2 “Difficult reservoirs and unconventional natural gas resources” report 2 INTRODUCTION Reliable natural gas supply becomes more and more important for world energy sector development. Especially this is visible in regions, where old and sophisticated gas infrastructure is a considerable part of regional industry and its stable work is necessary for successful economy development. In the same time such regions often are already poor by conventional gas reserves or have no more such reserves. And there is need for searching new sources of natural gas. This is challenge for exploration and production of natural gas requiring reviewing strategies of their development in near future. The most important questions are: how much gas still we can get from mature areas (and by what means), and how much gas we can get from difficult reservoirs and unconventional gas sources? From this point of view IGU Working Committee 1 (Exploration and Production of Natural Gas) has established for the triennium 2006-2009 two Study Groups: “Remaining conventional world gas resources and technological challenges for their development” and “Difficult reservoirs and unconventional natural gas resources”. The purposes for the first Group study were to make definition of such important term now using in gas industry like “mature area”, to show current situation with reserves and production in mature areas and forecast of future development, situation with modern technologies of produced gas monetization, Arctic gas prospects, special attention was paid to large Shtokman project. -

Eastwest Institute

EASTWEST INSTITUTE Ukraine, EU, Russia: Challenges and Opportunities for NewRelations A conference initiated and organized by the EastWest Institute, in cooperation with the Carpathian Foundation and Ukrainian partners: the Institute for Regional and Euro-Integration Studies "EuroRegio Ukraine" and the National Association of Regional Development Agencies Kyiv, 10-11 February 2005 Venue: "European Hall", President-hotel "Kyivski", Hospitalna str., 12 Languages: English and Ukrainian **Please Note: The Chatham House Rule Applies** Thursday, 10 February 2005 8.30 - 9.00 Registration 9.00 - 09.15 Words of Welcome and Opening Remarks Mr John Edwin Mroz, President and CEO, EastWest Institute 9.15-9.45 Keynote speaker: Mr Borys Tarasyuk, Minister for Foreign Affairs of Ukraine 9.45-11.00 Session I Ukraine after the changes: new priorities for the new leadership Challenge of the session: What are the expectations, tasks and practical needs of Ukraine's leadership? Chair: 1 Dr Oleksandr Pavlyuk, Acting Plead of External Co-operation, OSCE, Vienna Speakers: Mr Oleksandr Moroz, Leader, Socialist party of Ukraine Mr Oleksandr Zinchenko, State Secretary of Ukraine (tbc) Mr Volodymyr Vdovychenko, Mayor of the City of Slavutych Mr Boris Sobolev, Vice President of the Kyiv Bank Union Respondents: Mr Ofer Kerzner, Chairman of First Ukrainian Development, Kyiv Dr. Bohdan Hawrylyshyn, Chairman of the International Centre for Policy Studies, Kyiv 7 /.00-11.30 Special address: President Viktor Yushchenko (invited) 11.30-12.00 Coffee Break 12.00-13.45 Session II European Neighbourhood Policy versus CIS integration: does Ukraine have to choose? Challenge of the session: May the two frameworks of integration work together? Chair: Dr Vasil Hudak, Vice President and Brussels Centre Director, EastWest Institute, Brussels Speakers: Mr Ihor Dir, Head of Department for European integration, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine Ms Ana Palacio, Chairwoman of the Joint Parliamentary Committee for European Union Affairs and Former Foreign Minister of Spain, Madrid Mr. -

Novatek Pjsc

NOVATEK PJSC Primary Credit Analyst: Elena Anankina, CFA, Moscow + 7 49 5783 4130; [email protected] Secondary Contact: Alexander Griaznov, Moscow + 7 49 5783 4109; [email protected] Table Of Contents Credit Highlights Outlook Our Base-Case Scenario Company Description Peer Comparison Business Risk Financial Risk Liquidity Environmental, Social, And Governance Rating Above The Sovereign Issue Ratings - Subordination Risk Analysis Ratings Score Snapshot Related Criteria S&P GLOBAL RATINGS360 APRIL 2, 2021 1 © S&P Global Ratings. All rights reserved. No reprint or dissemination without S&P Global Ratings' permission. See Terms of Use/Disclaimer on the last page. Table Of Contents (cont.) Related Research S&P GLOBAL RATINGS360 APRIL 2, 2021 2 © S&P Global Ratings. All rights reserved. No reprint or dissemination without S&P Global Ratings' permission. See Terms of Use/Disclaimer on the last page. NOVATEK PJSC Business Risk: SATISFACTORY Issuer Credit Rating Vulnerable Excellent a- bbb bbb BBB/Stable/-- Financial Risk: MINIMAL Highly leveraged Minimal Anchor Modifiers Group/Gov't Russia National Scale NR/--/-- Credit Highlights Overview Key strengths Key risks Low leverage, with RUB222.1 billion of reported debt at year-end 2020, and High consolidated capital expenditure (capex), with about funds from operations (FFO) to debt above 60% in our base-case scenario RUB200 billion planned for 2021 Very low cost position Large LNG investment ambitions, where financing and project structure are yet to be confirmed Stable quasi-utility domestic gas business Increasing oil and gas industry risks from energy transition, including price volatility and growing ESG pressures Healthy profitability of joint ventures (notably Yamal LNG), and non-recourse Current U.S. -

The Study of Public Opinion on Industrial Mining in the Nefteyugansk District of Yugra © Said Kh

Arctic and North. 2017. No. 28 87 UDC 67.01 DOI: 10.17238/issn2221-2698.2017.28.106 The study of public opinion on industrial mining in the Nefteyugansk district of Yugra © Said Kh. Khaknazarov, Cand. Sci. (Geol.-min.), Head of the Research Depart- ment for Social and Economic Development and Monitoring. Tel: +79124180675. E-mail: [email protected] Ob-Ugriс Institute of Applied Researches and Developments, Khanty-Mansiysk, Russia. Abstract. In this article, we consider the views of respondents on the industrial development of mineral deposits on the example of the Nefteyugansky district, Yugra. The analysis of views regarding the development of mineral deposits rep- resents a comparative sociological study. It summarizes the results of a poll conducted in 2015 on the territory of Nefteyugansk district and earlier studies done in 2008 and 2012. The results of polls showed that most respondents had positive sentiments to the industrial mining. On the other hand, in contrast to 2008, in 2015, the proportion of people, who opposed the commercial develop- ment of mineral resources, got bigger. At the same time, most respondents believed that industrial mining resulted in environmental degradation of the area (district) of their residence. Keywords: industrial mining, public opinion, poll, environmental condition, respondents, small-numbered indigenous peoples of the North, experts, results of industrial mining The rapid growth and development of industrial facilities, new technologies, development of new mineral deposits, and creation of powerful industrial equipment represent a potential risk of industrial accidents and their negative consequences for human health and the environment. This is because the deposits of mineral resources that meet the industry needs are mainly on the territories of traditional nature use (TTNU) of indigenous peoples of the North (IPN). -

Russian Strategy Towards Ukraine's Presidential Election

BULLETIN No. 49 (49) August 19, 2009 © PISM Editors: Sławomir Dębski (Editor-in-Chief), Łukasz Adamski, Mateusz Gniazdowski, Beata Górka-Winter, Leszek Jesień, Agnieszka Kondek (Executive Editor), Łukasz Kulesa, Ernest Wyciszkiewicz Russian Strategy towards Ukraine’s Presidential Election by Jarosław Ćwiek-Karpowicz Dmitry Medvedev’s letter to Viktor Yushchenko is a clear signal of Russia’s intention to influ- ence internal developments in Ukraine, including the course of the presidential campaign. In the run-up to the January 2010 poll, unlike in the period preceding the Orange Revolution, Russia will very likely refrain from backing just a single candidate, and instead will seek a deepening of the existing divisions and further destabilization on the Ukrainian political scene, destabilization which it sees as helping to protect Russian interests in Ukraine. Medvedev’s Letter. In an open letter to Viktor Yushchenko, dated 11 August, Dmitry Medvedev put the blame for the crisis in bilateral relations on the Ukrainian president, and he explained that the arrival of the new ambassador to Kiev, Mikhail Zurabov—replacing Viktor Chernomyrdin, who was recalled last June—would be postponed. Medvedev accused his Ukrainian counterpart of having knowingly abandoned the principles of friendship and partnership with Russia during the past several years. Among the Yushchenko administration’s alleged anti-Russian actions, he listed weapons shipments and support extended to Georgia in last year’s armed conflict in South Ossetia; endeavors to gain -

Global Energy Company Company SCALE TECHNOLOGY RESPONSIBILITY

Global Energy Global Energy Company Company SCALE TECHNOLOGY RESPONSIBILITY Rosneft is the Russian oil Rosneft is the champion Rosneft is the biggest taxpayer Annual report 2013 industry champion and the of qualitative modernization in the Russian Federation. world’s biggest public oil and innovative change in the Active participation in the Annual report 2013 and gas company by proved Russian oil and gas industry. social life of the regions hydrocarbon reserves Proprietary solutions to of operations. and production. improve oil and synthetic Creating optimal conditions Unique portfolio of upstream liquid fuel production for professional development assets. performance. and high standards of social Leading positions for oshore Establishing R&D centers security and healthcare for development. in a partnership with global the employees. Growing role in the Asia- leaders in technology Unprecedented program Pacific markets. development and application. for land remediation. ROSNEFT Scale Technology Annual report online: www.rosneft.ru Responsibility www.rosneft.com/attach/0/58/80/a_report_2013_eng.pdf OUR RECORD ACHIEVEMENTS 551 RUB BLN RECORD NET INCOME +51% Page 136 4,694 RUB BLN RECORD REVENUES +52% Page 136 85 4 ,873 RUB BLN KBOED RECORD DIVIDENDS RECORD HYDROCARBONS PAID IN 2013 PRODUCTION +80.3%* Page 124 Page 28 90.1 42.1 MLN TONS* BCM** RECORD OIL GAS PRODUCTION, REFINING VOLUMES RUSSIA’s third largesT References to Rosneft Oil Company, Rosneft, or GAS PRODUCER the Company are to either Rosneft Oil Company or Rosneft Oil Company, its subsidiaries and affil- +46% iates, as the context may require. References to * TNK-BP assets accounted for from the date TNK-BP, TNK-BP company are to TNK-BP Group. -

Russia Intelligence” Be Conciliatory on the Gas Question

N°59 - July 3 2008 Published every two weeks/International Edition CONTENTS DIPLOMACY P. 1-2 Politics & Government c Will Russia place its bets on Yulia Timoshenko? DIPLOMACY cWill Russia place its bets on What’s to be done? The famous question posed in his time by Lenin is back on the agenda and, Yulia Timoshenko? with regard to Ukraine, will become increasingly acute in Moscow. Ukraine is once again the Kremlin’s ALERTS main diplomatic concern. The expansion of NATO to the East, the future of the Black Sea fleet and cViktor Chernomyrdin gets Sebastopol, and, of course, the gas question count among the most sensitive issues seen from Moscow. Af- ready to leave. ter having got its fingers burnt during the “orange revolution” at the end of 2004, Russia carefully kept out FOCUS of Ukraine’s political jousting including during the political crisis in Kyiv in May 2007 and during the early cThe Supreme Court, the new general election of 30 September last year. The approaching presidential election (expected at the end of theatre of the Confrontation 2009 or beginning of 2010) and the geopolitical stakes affecting Ukraine being considered in Moscow as between Viktor Yushchenko matters of the country’s vital interests, it is very likely that Russia is once again seeking to influence the and Yulia Timoshenko destiny of its neighbour. P. 3-4 Business & Networks In this context, the visit of the Ukrainian prime minister to Moscow on 28 June and her talks with her FOCUS opposite number Vladimir Putin, were awaited with interest. It is well known that until now Russia had c The Vanco affair constantly snubbed Yulia Timoshenko, considering her as not very dependable and out of control, and de- ALERTS spite the ideological chasm separating the Ukrainian president and his Russian opposite numbers, had pre- c Towards a re-launch of ferred to deal with Viktor Yushchenko.