Vowel Epenthesis in Vimeu Picard: a Preliminary Investigation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CONSEIL MUNICIPAL DE VILLERS BRETONNEUX Séance Du – 12 FEVRIER 2020

CONSEIL MUNICIPAL DE VILLERS BRETONNEUX Séance du – 12 FEVRIER 2020 - Du 06 FEVRIER 2020 - convocation du Conseil Municipal adressée individuellement par écrit à chacun des conseillers pour la séance du 12 FEVRIER 2020. ---------------- ORDRE DU JOUR - Aménagement de la RD 1029 (phase 1) : Signature Convention avec le Département de la Somme - Approbation mise à jour des statuts de la Communauté de Communes du Val de Somme - Arrêt de projet du Programme Local de l’Habitat 2020-2025 de la Communauté de Communes du Val de Somme : avis du Conseil municipal - Autorisation au Maire pour ester en justice - Tableau des effectifs des emplois permanents au 1er janvier 2020 - Personnel communal : Modification durée hebdomadaire emplois à temps non complet - Attribution de subvention d’opération rencontres australiennes 2020 - Don à l’Australie -------------------- L'An deux mil VINGT, le DOUZE FEVRIER à vingt heures trente le conseil municipal de la commune de Villers-Bretonneux, régulièrement convoqué, s’est réuni au nombre prescrit par la loi, dans le lieu habituel de ses séances sous la présidence de Monsieur Patrick SIMON, Maire. Présents : MM. et Mmes : SIMON P. - CARPENTIER P. - DURAND B. - MUSIDLAK P. - BECU C. - DECOTTEGNIE B. - FEUCHER J.M. - DUBOIS P. - DAMAY G. - HERBIN N. - VICART N. - NIVELLE J. – FRANCOIS B. - DINOUARD D.- DESMET J.M. - BLOOTACKER P. - FINAZ P. - FRANCOIS F. – LECOCQ S. - DIEU J.M. - LAMBERT A. - LAVOISIER E. - LECLERC J. - MALARME A. Absents excusés : Mmes : BEAURIN D. - MANOT C. Absents excusés ayant donné procuration : Mme HUYGHE P. ayant donné procuration à M. CARPENTIER P. Secrétaire de séance : Mme DUBOIS Patricia. La séance a été ouverte sous la présidence de Monsieur Patrick SIMON, Maire. -

Vallée De La Bresle »

Document d’objectifs NATURA 2000 FR n°22 00 363 « Vallée de la Bresle » TOME 1 : TEXTES Jean-Philippe BILLARD JUILLET 2012 Chargé de mission – EPTB Bresle DOCOB « Vallée de la Bresle » 1 Table des matières PREAMBULE ET RAPPEL SUR LA DIRECTIVE « HABITATS, FAUNE, FLORE » ..................... 4 I. Le contexte historique...................................................................................................................... 5 II. La procédure NATURA 2000… .................................................................................................... 5 A. Le comité de pilotage ................................................................................................................. 5 B. Le document d’objectifs ............................................................................................................. 6 C. Des contrats feront suite au DOCOB…...................................................................................... 6 PARTIE 1 : DESCRIPTION GENERALE DU SITE « VALLEE DE LA BRESLE ».......................... 7 I. Fiche d’identité du site FR 2200363................................................................................................ 8 II. Généralités géographiques du bassin de la Bresle........................................................................ 11 A. Les communes concernées ....................................................................................................... 11 B. Description générale du site..................................................................................................... -

Somme Aval Et Cours D'eau Côtiers

Schéma d’Aménagement et de Gestion des Eaux Somme aval et Cours d’eau côtiers Arrêté interpréfectoral du 6 août 2019 Rapport environnemental Table des matières 1. Résumé non technique .......................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Présentation du SAGE .......................................................................................................... 7 1.2 Les enjeux du territoire ....................................................................................................... 8 1.3 Les effets sur l’environnement ............................................................................................ 9 1.4 La mise en œuvre et le suivi ................................................................................................ 9 2. Présentation générale de l’évaluation environnementale ........................................................ 10 3. Les objectifs du SAGE, son contenu et l’articulation avec les autres plans et programmes ......... 11 3.1 Les objectifs de l’élaboration et le contenu du SAGE ........................................................ 11 3.1.1 Historique de la démarche du SAGE .......................................................................... 11 3.1.2 Le contenu du SAGE .................................................................................................. 12 3.1.3 Les mesures opérationnelles du SAGE ...................................................................... 13 3.2 L’articulation du SAGE avec les -

Convention Cadre Stratégie Littorale Bresle

Convention cadre stratégie littorale Les 3 volets de la stratégie littorale Bresle - Somme - Authie www. papibsa.org - 38 874 700 € I/ PAPI : LES AXES 1 - 2 - 3 - 4 - 5 - 6 - 7 7 septembre 2016 d’une démarche innovante en matière d’occupation temporaire et amélioration de la connaissance et de la résiliente dans les zones d’aléa conscienceAXE 1 : du risque - 1 150 200 € ■ Concilier développement urbain, prévision de zones de relocalisation ■ Capitalisation des références historiques pour sensibiliser la population et gestion des risques par un urbanisme résilient (mise en place de repères de crues/submersion/trait de côte) ■ Étude de stratégie foncière pour la mise en œuvre de la restructuration ■ Sensibilisation / communication et mise en place d’outils pédagogique long terme du territoire (Marquenterre et Bas-Champs) sur les risques pour les scolaires, les cadres territoriaux, les élus et le grand public actions de réduction de la vulnérabilite des ■ Information sur les activités économiques exposées au risque : personnesAXE 5 : et des biens - 3 301 700 € animation d’un réseau de correspondants ■ Connaissances : réalisation d’un suivi du littoral (morphologie) : levés ■ Adaptation des activités économiques en zone inondable : réalisation annuels, bancarisation, partage d’un guide d’adaptation des locaux Le PAPI Bresle-Somme-Authie (BSA) a été labellisé par la Commission Mixte Inondation le 5 novembre 2015 pour une durée de six ans. Il Constitution d’une banque de mesures compensatoires ■ Diagnostics de vulnérabilite pour les entreprises et infrastructures ■ définit une stratégie à court, moyen et long terme de gestion intégrée du trait de côte, à l’échelle du bassin de risque s’étendant de Berck- ■ Assistance aux communes pour la réalisation du Document économiques du territoire ■ Adaptation des établissements recevant du public (ERP) : santé, écoles, sur-Mer jusqu’au Tréport. -

Suivi Du Site Expérimental De Warloy- Baillon Et Prévision Des Crues De La Somme Rapport Final

Appui au SCHAPI 2012 – Module 2 : Suivi du site expérimental de Warloy- Baillon et prévision des crues de la Somme Rapport final BRGM/RP-62062-FR Février 2013 Appui au SCHAPI 2012 – Module 2 : Suivi du site expérimental de Warloy- Baillon et prévision des crues de la Somme Rapport final BRGM/RP-62062-FR Février 2013 Étude réalisée dans le cadre des projets de Service public du BRGM 2012-RIS-74 N. Amraoui, D. Thiéry et A. Wuilleumier Vérificateur : Approbateur : Nom : J.J. Seguin Nom : N. Dörfliger Date : 21/03/2013 Date : 08/07/2013 Signature : Signature : En l’absence de signature, notamment pour les rapports diffusés en version numérique, l’original signé est disponible aux Archives du BRGM. Le système de management de la qualité du BRGM est certifié AFAQ ISO 9001:2008. Mots-clés : Aquifère de la Craie, zone non saturée, modélisation globale, outils de prévision, crues, site expérimental de Warloy-Baillon, Bassin de la Somme. En bibliographie, ce rapport sera cité de la façon suivante : Amraoui N., Thiéry D., Wuilleumier A. (2012) – Appui au SCHAPI – Module 2- Suivi du site expérimental de Warloy-Baillon et prévision des crues de la Somme. Rapport final. BRGM/RP-62062- FR,86 p.,71 fig., 1tabl., 1ann. © BRGM, 2011, ce document ne peut être reproduit en totalité ou en partie sans l’autorisation expresse du BRGM. Appui au SCHAPI 2012 : Suivi du site expérimental de Warloy-Baillon et prévision des crues de la Somme Synthèse Dans le cadre de la convention entre le BRGM et la DGPR (Direction Générale de la Prévention des Risques) pour le -

Ribemont-Sur-Ancre

Ribemont-sur-Ancre (Somme) : bilan préliminaire et nouvelles hypothèses Jean-Louis Brunaux, Michel Amandry, Véronique Brouquier-Reddé, Louis-Pol Delestrée, Henri Duday, Gérard Fercoq Du Leslay, Thierry Lejars, Christine Marchand, Patrice Méniel, Bernard Petit, et al. To cite this version: Jean-Louis Brunaux, Michel Amandry, Véronique Brouquier-Reddé, Louis-Pol Delestrée, Henri Duday, et al.. Ribemont-sur-Ancre (Somme) : bilan préliminaire et nouvelles hypothèses. Gallia - Archéologie de la France antique, CNRS Éditions, 1999, 56, pp.177-283. 10.3406/galia.1999.3010. hal-01901778 HAL Id: hal-01901778 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01901778 Submitted on 16 Jan 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License Ribemont-sur-Ancre (Somme) Bilan préliminaire et nouvelles hypothèses Éditeur scientifique : Jean-Louis Brunaux* Michel Amandry, Véronique Brouquier-Reddé, Louis-Pol DelestrÉe, Henri Duday, Gérard Fercoq du Leslay, Thierry Lejars, Christine Marchand, Patrice Méniel, Bernard Petit, Béatrice Rogéré Mots-clés. Trophée, squelettes humains sans tête, armes celtiques, temple précoce de la fin du Ier s. avant J.-C, quadriportique flavien, temple sur podium pseudo-périptère, ordre corinthien, culte public. -

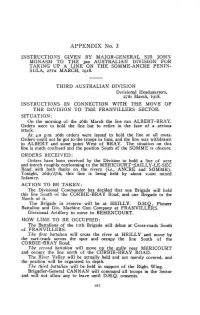

APPENDIX No. 3

APPENDIX No. 3 INSTRUCTIONS GIVEN BY MAJOR-GENERAL SIR JOHS MONASH TO THE ~RDAUSTRALIAN DIVISION FOR TAKING UP A LINE ON THE SOMME-ANCRE PENIN- SULA, Z~THMARCH, 1918. THIRD AUSTRALIAN DIVISION Divisional Headquarters, 27th March, 1918. INSTR ICT ONS IN CONNECTION WITH THE MOVE OF THE DIVISION TO THE FRANVILLERS SECTOR. SITUATION : On the morning of the 26th March the line ran ALBERT-BRAY. Orders were to hold the line but to retire in the face of a serious attack. At 4.0 pm. 26th orders were issued to hold the line at all costs. Orders could not be got to the troops in time, and the line was withdrawn to ALBERT and some point West of BRAY. The situation on this line is much confused and the position South of the SOMME is obscure. ORDERS RECEIVED : Orders have been received by the Division to hold a he of wire and trench roughly conforming to the MERICOURT-SAILLY-LE-SEC Road with both flanks on the rivers (Le., ANCRE and SOMME). Tonight, 26th/z7th, this line is being held by about 2,ooo mixed Infantry. ACTION TO BE TAKEN: The Divisional Commander has decided that one Brigade will hold this line South of the CORBIE-BRAY Road, and one Brigade to the North of it. The Brigade in reserve will be at HEILLY. D.H.Q, Pioneer Battalion and Div. Machiiie Gun Company at FRANVILLERS. Divisional Artillery to move to BEHENCOURT. HOW LINE TO BE OCCUPIED: The Battalions of the 11th Brigade will debus at Cross-roads South of FRANVILLERS. -

4 Blangy Sur Bresle – Amiens Horaires Valables a Compter Du 3 Sept

4 BLANGY SUR BRESLE – AMIENS HORAIRES VALABLES A COMPTER DU 3 SEPT. 2012 PERIODE SCOLAIRE PETITES VACANCES Jours de circulation > LMmJVS LMmJVS LMmJVS mS LMmJVS LMmJVS mS BLANGY SUR BRESLE Abri Place 1 06:00 1 06:00 BOUTTENCOURT Rue du Tréport 2 06:02 2 06:02 NESLETTE Grande Rue 3 06:07 3 06:07 NESLE L'HOPITAL Route de Paris 4 06:10 4 06:10 SENARPONT Route du Tréport 5 06:15 06:49 12:20 5 06:15 12:20 SENARPONT Place du Général Leclerc 6 06:16 06:50 12:21 6 06:16 12:21 NEUVILLE COPPEGUEULE La Rosière 7 06:22 06:56 12:26 7 06:22 12:26 NEUVILLE COPPEGUEULE Eglise 8 06:22 06:56 12:26 8 06:22 12:26 BEAUCAMPS LE VIEUX Salle des fêtes 9 06:26 07:00 12:30 9 06:26 12:30 BEAUCAMPS LE VIEUX Place de l'Argilière 10 06:27 07:01 12:31 10 06:27 12:31 LE QUESNE Haut 11 06:30 | 12:34 11 06:30 12:34 LE QUESNE Mairie 12 06:30 | 12:34 12 06:30 12:34 LIOMER Le Buquet Blanc 13 06:32 | 12:37 13 06:32 12:37 LIOMER Place de la Mairie 14 06:33 | 12:38 14 06:33 12:38 BROCOURT Rue d'Hornoy 15 | 07:05 | 15 | | HORNOY LE BOURG Place 16 06:40 07:13 12:48 16 06:40 12:48 HORNOY LE BOURG Hallivillers Centre 17 06:44 | 12:50 17 06:44 12:50 THIEULLOY L'ABBAYE Abri Ecole 18 | | | 18 | | CAMPS EN AMIENOIS Verte et Cornet 19 06:46 | 12:52 19 06:46 12:52 CAMPS EN AMIENOIS Eglise 20 06:47 | 12:54 20 06:47 12:54 THIEULLOY L'ABBAYE Mairie 21 | 06:30 | | 21 | 06:30 | SAINT AUBIN MONTENOY Eglise 22 | 06:36 | | 22 | 06:36 | SAINT AUBIN MONTENOY Montenoy 23 | 06:41 | | 23 | 06:41 | FRESNOY AU VAL Salle des fêtes 24 | 06:46 | | 24 | 06:46 | MOLLIENS DREUIL Rue du Général Leclerc 25 -

Presentation Du Bassin Versant De La Somme Et Diagnostic

0 SOMMAIRE SOMMAIRE AVANT-PROPOS I. GENESE D’UNE POLITIQUE GLOBALE DE PREVENTION DES INONDATIONS SUR LE BASSIN DE LA SOMME 10 DE LA POST-CRISE AU RETOUR D’EXPERIENCE : LA COMMISSION D’ENQUETE SENATORIALE ET SES PRECONISATIONS (2001) 11 LE TEMPS DE L’URGENCE ET DU RETOUR A LA NORMALE : PROGRAMME « VALLEE ET BAIE DE SOMME » (2001-2006) 13 PREMICES DE LA GESTION DU RISQUE : LE PREMIER PROGRAMME D’ACTIONS DE PREVENTION DES INONDATIONS (2003-2006) 15 PROGRAMME D’AMENAGEMENT COMPLEMENTAIRE ISSU DE L’ETUDE DE MODELISATION HYDRAULIQUE : UNE PREMIERE ORIENTATION STRATEGIQUE VERS LA REDUCTION DE L’ALEA 16 ELABORATION D’UN PROGRAMME DE TRAVAUX DE PREVENTION ET DE LUTTE CONTRE LES INONDATIONS DE LA SOMME (2010) : AFFINER ET POURSUIVRE LES ORIENTATIONS STRATEGIQUES DE REDUCTION DE L’ALEA 20 LE PLAN SOMME I (2007-2014) : VERS UNE GESTION COHERENTE ET INTEGREE DE LA PREVENTION DES INONDATIONS 22 II. LES OUTILS DE PLANIFICATION ET DE PROGRAMMATION EN VIGUEUR 26 LE PLAN SOMME II (2015-2020) : S’ORIENTER VERS LA REDUCTION DE LA VULNERABILITE DES ENJEUX 26 UN PAPI SPECIFIQUE AU LITTORAL PICARD POUR GERER LE RISQUE DE SUBMERSION MARINE 34 LES SCHEMAS D’AMENAGEMENT ET DE GESTION DES EAUX (SAGE) 40 1) LE SAGE HAUTE-SOMME 40 2) LE SAGE SOMME AVAL COURS D’EAU COTIERS 49 III. 2011-2017 : LE PREMIER CYCLE DE LA DIRECTIVE INONDATION 54 1ERE ETAPE : L’EVALUATION PRELIMINAIRE DES RISQUES D’INONDATION (EPRI) 54 2EME ETAPE : LES TERRITOIRES A RISQUE IMPORTANT D’INONDATION (TRI) 56 3EME ETAPE : LE PLAN DE GESTION DES RISQUES D’INONDATION (PGRI) 2016-2021 56 4EME ETAPE : LES STRATEGIES LOCALES DE GESTION DES RISQUES D’INONDATION (SLGRI) 2016-2022 60 UN CADRE NATIONAL POUR L’ACTION : LA STRATEGIE NATIONALE DE GESTION DES RISQUES D’INONDATION 60 IV. -

Sectorisation Par Commune

Conseil départemental de la Somme / Direction des Collèges Périmètre de recrutement des collèges par commune octobre 2019 Code communes du secteur Libellé du secteur collège commune 80001 Abbeville voir sectorisation spécifique 80002 Ablaincourt-Pressoir CHAULNES 80003 Acheux-en-Amiénois ACHEUX EN AMIENOIS 80004 Acheux-en-Vimeu FEUQUIERES EN VIMEU 80005 Agenville BERNAVILLE 80006 Agenvillers NOUVION AGNIERES (ratt. à HESCAMPS) POIX 80008 Aigneville FEUQUIERES EN VIMEU 80009 Ailly-le-Haut-Clocher AILLY LE HAUT CLOCHER 80010 Ailly-sur-Noye AILLY SUR NOYE 80011 Ailly-sur-Somme AILLY SUR SOMME 80013 Airaines AIRAINES 80014 Aizecourt-le-Bas ROISEL 80015 Aizecourt-le-Haut PERONNE 80016 Albert voir sectorisation spécifique 80017 Allaines PERONNE 80018 Allenay FRIVILLE ESCARBOTIN 80019 Allery AIRAINES 80020 Allonville RIVERY 80021 Amiens voir sectorisation spécifique 80022 Andainville OISEMONT 80023 Andechy ROYE ANSENNES ( ratt. à BOUTTENCOURT) BLANGY SUR BRESLE (76) 80024 Argoeuves AMIENS Edouard Lucas 80025 Argoules CRECY EN PONTHIEU 80026 Arguel BEAUCAMPS LE VIEUX 80027 Armancourt ROYE 80028 Arquèves ACHEUX EN AMIENOIS 80029 Arrest ST VALERY SUR SOMME 80030 Arry RUE 80031 Arvillers MOREUIL 80032 Assainvillers MONTDIDIER 80033 Assevillers CHAULNES 80034 Athies HAM 80035 Aubercourt MOREUIL 80036 Aubigny CORBIE 80037 Aubvillers AILLY SUR NOYE 80038 Auchonvillers ALBERT PM Curie 80039 Ault MERS LES BAINS 80040 Aumâtre OISEMONT 80041 Aumont AIRAINES 80042 Autheux BERNAVILLE 80043 Authie ACHEUX EN AMIENOIS 80044 Authieule DOULLENS 80045 Authuille -

Selon Les Termes Du Décret N°2007-865 Du 14 Mai 2007 Relatif Au Contrôle Des Structures Des Exploitations Agricoles Et Modif

Selon les termes du décret n°2007-865 du 14 mai 2007 relatif au contrôle des structures des exploitations agricoles et modifiant le code rural, le service chargé de l’instruction fait procéder à une publicité. Vous pouvez déposer une demande portant sur les surfaces concernées avant la date d’expiration. Pour connaître l’adresse des propriétaires, vous pouvez téléphoner le matin à la DDTM au 03.22.97.23.36. 31 août 2015 DOSSIER EXPIRATION SURFACE REFERENCES N°DOSSIER DATE DEPOT LIEU DES TERRES SURFACE Civilité NOM PROPRIETAIRE ADRESSE CP VILLE COMMUNE COMPLET DELAI 3 MOIS DEMANDEE CADASTRALES 15463 28-août-15 31-août-15 01-déc.-15 41,4857 BONNAY Z 104 1,3066 Monsieur CHOQUET Daniel 17 Rue de Raincheval 80560 TOUTENCOURT 15463 28-août-15 31-août-15 01-déc.-15 41,4857 BONNAY Z 33 0,9119 Monsieur CHOQUET Hubert 7 Rue Terraine 80560 TOUTENCOURT 15463 28-août-15 31-août-15 01-déc.-15 41,4857 FRANVILLERS Z 40 1,466 Monsieur CHOQUET Daniel 17 Rue de Raincheval 80560 TOUTENCOURT 15463 28-août-15 31-août-15 01-déc.-15 41,4857 FRANVILLERS ZB 1 0,3879 Monsieur CHOQUET Daniel 17 Rue de Raincheval 80560 TOUTENCOURT 15463 28-août-15 31-août-15 01-déc.-15 41,4857 HEILLY T 48 0,414 Monsieur CHOQUET Hubert 7 Rue Terraine 80560 TOUTENCOURT 15463 28-août-15 31-août-15 01-déc.-15 41,4857 HEILLY Z 38 0,845 Monsieur CHOQUET Daniel 17 Rue de Raincheval 80560 TOUTENCOURT 15463 28-août-15 31-août-15 01-déc.-15 41,4857 TOUTENCOURT D 610 0,375 Monsieur CHOQUET Daniel 17 Rue de Raincheval 80560 TOUTENCOURT 15463 28-août-15 31-août-15 01-déc.-15 41,4857 TOUTENCOURT -

SEPTEMBRE 2017 Sommeval BULLETIN INTERCOMMUNAL LE JOURNAL D’Informationde DE LA COMMUNAUTÉ DE COMMUNES DU VAL DE SOMME

42 / SEPTEMBRE 2017 sommeVAL BULLETIN INTERCOMMUNAL LE JOURNAL D’INFORMATIONde DE LA COMMUNAUTÉ DE COMMUNES DU VAL DE SOMME ENVIRONNEMENT 03 La nouvelle déchetterie-recyclerie à votre service TRAVAUX TOURISME TERRITOIRE Les travaux sur le territoire 06 Une nouvelle signalétique 14 Vaux-s/Somme / Vaire/s-Corbie 18 www.valdesomme.com SOMMAIRE Edito 3-5 ENVIRONNEMENT • La nouvelle déchetterie Le Val de Somme en perpétuel mouvement • Les résultats du concours • Tarification incitative A la lecture de ce numéro vous constaterez qu’il s’est passé beaucoup d’évènements au sein 6-7 TRAVAUX de la Communauté de Communes du Val de Somme durant les mois d’été. • Les travaux sur le territoire Il s’agit notamment de travaux de voirie, de création de points d’apport volontaires enterrés 8-13 ACTUALITÉS pour la collecte du verre et du papier, ou bien encore la réalisation d’aires de jeux et de parcours sportifs. • Les artisans et le tourisme • Un parcours santé à Heilly Il y a eu également de nombreuses animations organisées par la médiathèque et par l’office • L’Office de tourisme • “Les Avenues de l’honneur” de tourisme, autour du patrimoine historique, naturel, ou artisanal avec les visites d’ateliers. • Le PLUI Avec des nouveautés très appréciées des touristes mais surtout de tous les habitants du Val • La CCVS et la Fête dans la Rue de Somme. • Les maires et leurs administrés • Les Ambassadeurs Juniors Une rentrée riche en actions • Les chauves-souris à Bonnay • Le jeu de boule à la plume Le dynamisme de la Communauté de Communes s’inscrit également dans les services à • “Les Petites Madames” l’habitant.