Government of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines National

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines INTRODUCTION located on Saint Vincent, Bequia, Canouan, Mustique, and Union Island. Saint Vincent and the Grenadines is a multi-island Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, like most of state in the Eastern Caribbean. The islands have a the English-speaking Caribbean, has a British combined land area of 389 km2. Saint Vincent, with colonial past. The country gained independence in an area of 344 km2, is the largest island (1). The 1979, but continues to operate under a Westminster- Grenadines include 7 inhabited islands and 23 style parliamentary democracy. It is politically stable uninhabited cays and islets. All the islands are and elections are held every five years, the most accessible by sea transport. Airport facilities are recent in December 2010. Christianity is the Health in the Americas, 2012 Edition: Country Volume N ’ Pan American Health Organization, 2012 HEALTH IN THE AMERICAS, 2012 N COUNTRY VOLUME dominant religion, and the official language is fairly constant at 2.1–2.2 per woman. The crude English (1). death rate also remained constant at between 70 and In 2001 the population of Saint Vincent and 80 per 10,000 population (4). Saint Vincent and the the Grenadines was 102,631. In 2006, the estimated Grenadines has experienced fluctuations in its population was 100,271 and in 2009, it was 101,016, population over the past 20 years as a result of a decrease of 1,615 (1.6%) with respect to 2001. The emigration. According to the CIA World Factbook, sex distribution of the population in 2009 was almost the net migration rate in 2008 was estimated at 7.56 even, with males accounting for 50.5% (50,983) and migrants per 1,000 population (5). -

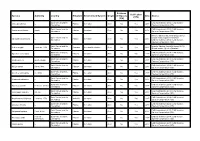

GRIIS Records of Verified Introduced and Invasive Species

Evidence Verification Species Authority Country Kingdom Environment/System Origin of Impacts Date Source (Y/N) (Y/N) Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Abrus precatorius L. Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Acacia auriculiformis Benth. Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Invasive Species Specialist Group (2015). Saint Vincent and the Global Invasive Species Database. Adenanthera pavonina L. Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the Invasive Species Specialist Group (2015). Aedes aegypti Linnaeus, 1762 Animalia terrestrial/freshwater Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Global Invasive Species Database. Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Ageratum conyzoides L. Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Albizia procera Benth. (Roxb.) Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Albizia saman (Jacq.) Merr. Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Aleurites moluccanus (L.) Willd. Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Allamanda cathartica L. Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Alpinia purpurata K.Schum. (Vieill.) Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). -

SAINT VINCENT and the GRENADINES Pilot Program For

SAINT VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES PPCR PHASE 1 PROPOSAL SAINT VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES Pilot Program for Climate Resilience (PPCR) PHASE ONE PROPOSAL 1 SAINT VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES PPCR PHASE 1 PROPOSAL Contents Glossary of Terms and Abbreviations .................................................................................. 5 Summary of Phase 1 Grant Proposal ................................................................................... 7 1.0 PROJECT BACKGROUND....................................................................................... 10 1.1 National Overview .................................................................................................. 11 1.1.1. Country Context ......................................................................................................... 11 2.0. Vulnerability Context .................................................................................................. 14 2.1 Climate .................................................................................................................... 14 2.1.1 Precipitation ............................................................................................................... 14 2.1.2 Temperature ................................................................................................................ 15 2.1.3 Sea Level Rise ............................................................................................................. 15 2.1.4 Climate Extremes ....................................................................................................... -

The University of Chicago the Creole Archipelago

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO THE CREOLE ARCHIPELAGO: COLONIZATION, EXPERIMENTATION, AND COMMUNITY IN THE SOUTHERN CARIBBEAN, C. 1700-1796 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY TESSA MURPHY CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MARCH 2016 Table of Contents List of Tables …iii List of Maps …iv Dissertation Abstract …v Acknowledgements …x PART I Introduction …1 1. Creating the Creole Archipelago: The Settlement of the Southern Caribbean, 1650-1760...20 PART II 2. Colonizing the Caribbean Frontier, 1763-1773 …71 3. Accommodating Local Knowledge: Experimentations and Concessions in the Southern Caribbean …115 4. Recreating the Creole Archipelago …164 PART III 5. The American Revolution and the Resurgence of the Creole Archipelago, 1774-1785 …210 6. The French Revolution and the Demise of the Creole Archipelago …251 Epilogue …290 Appendix A: Lands Leased to Existing Inhabitants of Dominica …301 Appendix B: Lands Leased to Existing Inhabitants of St. Vincent …310 A Note on Sources …316 Bibliography …319 ii List of Tables 1.1: Respective Populations of France’s Windward Island Colonies, 1671 & 1700 …32 1.2: Respective Populations of Martinique, Grenada, St. Lucia, Dominica, and St. Vincent c.1730 …39 1.3: Change in Reported Population of Free People of Color in Martinique, 1732-1733 …46 1.4: Increase in Reported Populations of Dominica & St. Lucia, 1730-1745 …50 1.5: Enslaved Africans Reported as Disembarking in the Lesser Antilles, 1626-1762 …57 1.6: Enslaved Africans Reported as Disembarking in Jamaica & Saint-Domingue, 1526-1762 …58 2.1: Reported Populations of the Ceded Islands c. -

List of Projects- Stewardfish Microgrants Scheme for Caribbean Fisherfolk Organisations

List of projects- StewardFish Microgrants Scheme for Caribbean Fisherfolk Organisations On July 1, 2020 CANARI launched the call for applications for the USD20,000 StewardFish Microgrants Scheme for Caribbean Fisherfolk Organisations. The overall goal of the microgrant scheme is to provide support to Caribbean fisherfolk organisations for organisational strengthening initiatives that will enhance their capacity to participate in coastal and marine resources governance and management, including ecosystem stewardship. The call targeted the following five fisherfolk organisations participating in StewardFish: 1. Barbuda Fisherfolk Association – Antigua and Barbuda 2. Barbados National Union of Fisherfolk Organisations (BARNUFO) – Barbados 3. Guyana National Fisherfolk Organisation (GNFO)- Guyana 4. Saint Lucia Fisherfolk Cooperative Society Limited – Saint Lucia 5. Saint Vincent and the Grenadines National Fisherfolks Co-Operative Limited (SVGNFO) – Saint Vincent and the Grenadines Each of the targeted fisherfolk organisations successfully submitted proposals to the microgrant scheme and were each awarded a USD4,000 microgrant for their projects which will run from November 2020 to April 2021. Table 1: List of StewardFish fisherfolk organisational strengthening projects Fisherfolk organisation Project title Project goal Barbados National iFish: Piloting an online To promote organisational strengthening Union of Fisherfolk platform for of BARNUFO to effectively mobilise Organizations organisational resources and build the capacity of its (BARNUFO) -

Deployment of an AWAC Off the East Coast of St Vincent, 2018-2019 Judith Wolf, Giles Williams and James Ayliffe

National Oceanography Centre Research & Consultancy Report No. 69 Deployment of an AWAC off the east coast of St Vincent, 2018-2019 Judith Wolf, Giles Williams and James Ayliffe October 2019 This report is part of the NOC-led project “Climate Change Impact Assessment: Ocean Modelling and Monitoring for the Caribbean CME states”, 2018-2019; under the Commonwealth Marine Economies (CME) Programme in the Caribbean. National Oceanography Centre Joseph Proudman Building 6 Brownlow St Liverpool L3 5DA UK email: [email protected] 1 2 Table of Contents Summary .............................................................................................................................. 5 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Background, aim and objectives of the study .......................................................... 7 1.2 Study Area – Saint Vincent and the Grenadines ..................................................... 7 1.3 Oceanographic description of the study area .......................................................... 9 2 Purchase of a wave gauge for St Vincent and Grenadines .......................................... 10 3 AWAC deployment ....................................................................................................... 11 3.1 July-October 2018................................................................................................. 14 3.2 January-March 2019 ............................................................................................ -

Meeting the Managua Challenge National

Meeting The Managua Challenge In November 2000, the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL) challenged governments of the Americas to accelerate their destruction of stockpiled antipersonnel mines ahead of the September 2001 meeting of States Parties to the 1997 Mine Ban Treaty, which will be held in Managua, Nicaragua. It also urged the remaining signatories and non- signatories to fully join the treaty by September 2001 and for all States Parties to submit their initial transparency reports as required under Article 7 of the ban treaty. An update on this Managua Challenge shows significant progress made by many countries since November 2000 to meet the Challenge: Three signatories ratified: Chile, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Uruguay. Three States Parties have completed stockpile destruction: Ecuador, Honduras, and Peru. Argentina, Chile, Nicaragua, and Uruguay destroyed some stockpiled mines. Six more States Parties have submitted their initial transparency reports:Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Grenada, Guatemala, Paraguay. Two States Parties enacted national implementation legislation in 2001:Brazil and Trinidad and Tobago. One States Party will reduce the number of antipersonnel mines retained for training and development, as permitted under the Article 3 of the treaty: Peru will reduce the number from 9,526 to 5,578. Thirty of the thirty-five countries in the Americas region are State Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty. Since November 2000, there have been three ratifications: Uruguay (7 June 2001), Saint Vincent and the Grenadines (1 August 2001), and Chile (10 September 2001). Three remaining signatories that have not ratified: Guyana, Haiti, and Suriname. Cuba and the United States remain the only two countries in the region that have not joined the Mine Ban Treaty. -

On Leaving and Joining Africanness Through Religion: the 'Black Caribs' Across Multiple Diasporic Horizons

Journal of Religion in Africa 37 (2007) 174-211 www.brill.nl/jra On Leaving and Joining Africanness Th rough Religion: Th e ‘Black Caribs’ Across Multiple Diasporic Horizons Paul Christopher Johnson University of Michigan-Ann Arbor, Center for Afroamerican and African Studies, 505 S. State St./4700 Haven, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1045, USA [email protected] Abstract Garifuna religion is derived from a confluence of Amerindian, African and European anteced- ents. For the Garifuna in Central America, the spatial focus of authentic religious practice has for over two centuries been that of their former homeland and site of ethnogenesis, the island of St Vincent. It is from St Vincent that the ancestors return, through spirit possession, to join with their living descendants in ritual events. During the last generation, about a third of the population migrated to the US, especially to New York City. Th is departure created a new dia- sporic horizon, as the Central American villages left behind now acquired their own aura of ancestral fidelity and religious power. Yet New-York-based Garifuna are now giving attention to the African components of their story of origin, to a degree that has not occurred in homeland villages of Honduras. Th is essay considers the notion of ‘leaving’ and ‘joining’ the African diaspora by examining religious components of Garifuna social formation on St Vincent, the deportation to Central America, and contemporary processes of Africanization being initiated in New York. Keywords Garifuna, Black Carib, religion, diaspora, migration Introduction Not all religions, or families of religions, are of the diasporic kind. -

St Vincent & the Grenadines

St Vincent & the Grenadines RISK & COMPLIANCE REPORT DATE: May 2017 KNOWYOURCOUNTRY.COM Executive Summary - St Vincent & the Grenadines Sanctions: None FAFT list of AML No Deficient Countries US Dept of State Money Laundering Assessment Higher Risk Areas: Not on EU White list equivalent jurisdictions Offshore Finance Centre Compliance with FATF 40 + 9 Recommendations Medium Risk Areas: Weakness in Government Legislation to combat Money Laundering Corruption Index (Transparency International & W.G.I.)) Failed States Index (Political Issues)(Average Score) Major Investment Areas: Agriculture - products: bananas, coconuts, sweet potatoes, spices; small numbers of cattle, sheep, pigs, goats; fish Industries: tourism; food processing, cement, furniture, clothing, starch Exports - commodities: bananas, eddoes and dasheen (taro), arrowroot starch; tennis racquets Exports - partners: Trinidad and Tobago 15.2%, St. Lucia 13.5%, Turkey 12.1%, Barbados 11.2%, Dominica 8.9%, Grenada 8.5%, Antigua and Barbuda 7.6% (2012) Imports - commodities: foodstuffs, machinery and equipment, chemicals and fertilizers, minerals and fuels Imports - partners: Singapore 27%, Trinidad and Tobago 24.1%, US 18.3%, China 5.4%, Barbados 5.3% (2012) 1 Investment Restrictions: The Government of St. Vincent and the Grenadines, through Invest SVG, strongly encourages foreign direct investment in St. Vincent and the Grenadines, particularly in industries that create jobs and earn foreign currency. St. Vincent and the Grenadines is an emerging and developing investment arena. The government is pursuing investment in niche markets, particularly Tourism, International Financial Services, Agro-Processing, Light Manufacturing and Information and Communication Technology (ICT). There is a constitutional right for nationals and non-nationals to establish and own private enterprises and private property in St. -

Resilient Housing and Affordability Assessments

Resilient Housing and Affordability Assessments Context and Objectives The housing sector in Caribbean nations is often the most financially affected sector in the aftermath of natural disasters, such as was the case when hurricanes Maria and Irma struck the region in 2017. The vulnerabilities of the housing sector are exacerbated by increasing urbanization, which has had a major impact in Caribbean land and housing markets. The availability of quality and affordable housing has not been able to meet the demand as more people move to urban centers looking for better opportunities. The limited availability of serviced land is another significant contributor to skyrocketing costs that price out households looking for affordable housing. As a result, these households end up living in low-quality structures to meet their housing needs, making them especially vulnerable to natural disasters. This situation has created a need for a comprehensive reform of regional housing policies This Technical Assistance (TA) supports the governments of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, the Dominican Republic, and Saint Lucia in undertaking such reforms through a better understanding of the links between urbanization, supply constraints, housing affordability, and the increasing vulnerability of the housing sector to natural disasters. The objective is to support each government to undertake an analysis to address the situation, and to design roadmaps for further steps based on those efforts. Main Activities Activities carried out by the TA are organized into the following three components, with some variability for each country: • Component 1: Rapid Housing Sector Assessment: This component is developed on field and desk research and through consultations with housing sector stakeholders including the government and private sector actors such as developers, builders, rental housing organizations, civil society, and microfinancing institutions. -

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

Mr. President, Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen: This 59 th Session of the General Assembly, coincides with the twenty-fifth anniversary of the independence of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. The last quarter of a century has been a mighty challenge for the people of my country to develop in a world increasingly indifferent to the particular problems of small, poor developing states. But it is a challenge that the citizens of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines have embraced with courage, fortitude and hope - never doubting our ability to survive, thrive and ultimately prosper as we contribute to the uplifting of our unique, independent, distinctive and noble Caribbean civilisation. Thus far, our country has progressed but much more remains to be done. We look forward to succeeding in our quest for self-mastery. Mr. President, I congratulate you on your assumption of the Presidency of the 59 th Session of the General Assembly. We are confident that you will perform your duties with dignity and skill. Let me just say, Mr. President, that you do have a hard act to follow. Your predecessor, our esteemed Mr. Julian Hunte, is a distinguished son of the Caribbean, who hails from our sister island, St. Lucia. He made us proud in his stint as President of the General Assembly. Mr. President, the peoples of the Caribbean and the Southern United States are still traumatized by the devastation caused by hurricanes in this season. Jamaica, the Bahamas, the Cayman Islands, Haiti, Cuba and other Caribbean countries, including my own, have been severely affected, but our nearest neighbour, Grenada, has suffered cataclysmic destruction and is now in a state of national crisis. -

CBD Strategy and Action Plan

SAINT VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES THE NATIONAL BIODIVERSITY STRATEGY AND ACTION PLAN Submitted To Sustainable Development Unit Ministry of Finance, Economic Planning, Sustainable Development, and Information Technology Saint Vincent & the Grenadines Revised National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan 2017 Revised National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (2015 - 2020) Sustainable Development Unit Ministry of Finance, Economic Planning, Sustainable Development, and Information Technology 1st Floor Administrative Building, Kingstown Saint Vincent and the Grenadines October 2017 Photo Credits Front Page 1. Aerial view of the Tobago Cays Marine Park (Courtesy A. DeGraff) 2. Soil Conservation Techniques at Argyle, St. Vincent (Courtesy Nicholas Stephens) 3. Leatherback monitoring in Bloody Bay, Union Island (Courtesy Union Island Environmental Attackers) ii | Page Saint Vincent & the Grenadines Revised National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan 2017 Table of Contents Abbreviations and Acronyms ........................................................................................................................ ii Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 1 ES1. The Status of Biodiversity ................................................................................................................. 1 ES2. The Commercial Value of Biodiversity .............................................................................................